Holme Cultram Abbey an Archaeological and Historical Guide 3 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11E5: Dubmill Point to Silloth

Cumbria Coastal Strategy Technical Appraisal Report for Policy Area 11e5 Dubmill Point to Silloth (Technical report by Jacobs) CUMBRIA COASTAL STRATEGY - POLICY AREA 11E5 DUBMILL POINT TO SILLOTH Policy area: 11e5 Dubmill Point to Silloth Figure 1 Sub Cell 11e St Bees Head to Scottish Border Location Plan of policy units. Baseline mapping © Ordnance Survey: licence number 100026791. 1 CUMBRIA COASTAL STRATEGY - POLICY AREA 11E5 DUBMILL POINT TO SILLOTH 1 Introduction 1.1 Location and site description Policy units: 11e5.1 Dubmill Point to Silloth (priority unit) Responsibilities: Allerdale Borough Council Cumbria County Council United Utilities Location: This unit lies between the defended headland of Dubmill Point and Silloth Harbour to the north. Site overview: The shoreline is mainly low lying, characterised by a wide mud, sand and shingle foreshore, fronting low lying till cliffs and two belts of dunes; at Mawbray and at Silloth. The lower wide sandy foreshore is interspersed by numerous scars, including Dubmill Scar, Catherinehole Scar, Lowhagstock Scar, Lee Scar, Beck Scar and Stinking Crag. These scars are locally important for wave dissipation and influence shoreline retreat. The behaviour of this shoreline is strongly influenced by the Solway Firth, as the frontage lies at the estuary’s lower reaches. Over the long term, the foreshore has eroded across the entire frontage due to the shoreward movement of the Solway Firth eastern channel (Swatchway), which has caused narrowing of the intertidal sand area and increased shoreline exposure to tidal energy. The Swatchway currently lies closer to the shoreline towards the north of the frontage. There is a northward drift of sediment, but the southern arm of Silloth Harbour intercepts this movement, which helps stabilise the beach along this section. -

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Peat Database Results Cumbria

Allonby, Cumbria Record ID 528 Authors Year Tooley, M. 1985b Location description Deposit location Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available No Notes Moor log. Bibliographic reference Tooley, M. 1985b 'Sea level changes and coastal morphology in North-west England' in 'The Geomorphology of North-west England', (ed.s) Johnson, R., 94-121, Manchester: Manchester University Press. Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 1 of 23 Annas Mouth, Cumbria Record ID 527 Authors Year Tooley, M. 1985b Location description Deposit location SD 0768 8841 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available +6.6 m OD No Notes Bibliographic reference Tooley, M. 1985b 'Sea level changes and coastal morphology in North-west England' in 'The Geomorphology of North-west England', (ed.s) Johnson, R., 94- 121, Manchester: Manchester University Press. Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 2 of 23 Barrow Harbour, Cumbria Record ID 406 Authors Year Kendall, W. 1900 Location description Deposit location [c. SD 217 653 - middle of harbour] Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Buried peats. Hard, consolidated, dry, laminated deposit overlain by marine clays, silts and sands. Valves of intertidal mollusc (Scrobularia) and vertebrae of whales in silty clay overlying the peat. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available No Notes Referred to in Tooley (1974). Bibliographic reference Kendall, W. 1900 'Submerged peat mosses, forest remains and post-glacial deposits in Barrow Harbour', Tranactions of the Barrow Naturalists' Field Club, 3(2), 55-63. -

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

North West Inshore and Offshore Marine Plan Areas

Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas MMO 1134: Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas September 2018 Report prepared by: Land Use Consultants (LUC) Project funded by: European Maritime Fisheries Fund (ENG1595) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Version Author Note 0.1 Sally First draft desk-based report completed May 2015 Marshall Paul Macrae 1.0 Paul Macrae Updated draft final report following stakeholder consultation, August 2018 1.1 Chris MMO Comments Graham, David Hutchinson 2.0 Paul Macrae Final report, September 2018 2.1 Chris Independent QA Sweeting © Marine Management Organisation 2018 You may use and re-use the information featured on this website (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ to view the licence or write to: Information Policy Team The National Archives Kew London TW9 4DU Email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Marine Management Organisation Lancaster House Hampshire Court Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 7YH Tel: 0300 123 1032 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gov.uk/mmo Disclaimer This report contributes to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) evidence base which is a resource developed through a large range of research activity and methods carried out by both MMO and external experts. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of MMO nor are they intended to indicate how MMO will act on a given set of facts or signify any preference for one research activity or method over another. -

Farmers. Dixon William, Joiner and Cartwright, Pelutho Anderson J Oseph (Hind), N Ewtown Edmondson Wm., Grocer, Provision Dealer, Ham Anm;Trong Mrs

• • 224 NORTHERN OR ESKDALE PARLIAMENTARY DIVISION. Akeshaw, that is, Oakwood, is situated on the north bank of the Crummock Beck, five miles from the Abbey. At Overby is a small Reading Room and Library containing about fifty volumes, established in 1897. CHARITIES. The late John Longcake, Esq., of Pelutho, left by will in 1873 the interest of £600 to the poor cottagers of this parish, and the residue of his estate, after the payment of certain legacies, he ordered to be invested in the names of seven trustees, and the interest thereof to be devoted to the promotion of religion and education in the townships of Holme Abbey, Holme Low, and Holme St. Cuthbert's. " The testator bequeaths to the incumbent and church wardens of Holme St. Cuthbert's, a scholarship of £40, for three years, to assist any clever boy attending the school, in obtaining a higher education, and to the incumbent and churchwardens of Holme Abbey £10 for Aldoth School; £20 to the Abbey School; and to the incumbent and wardens of St. Paul's, for Silloth School, £20 per annum, to assist any deserving boy, and the trustees are directed that within twelve months after his death to set apart, and transfer into the names of the several incumbents sufficient Government stock as wo11ld answer the several endowments. The sum of £14 18s. is distributed annually to the poor. HOLME ST. CUTHBERTS. School Board--William Edmondson, chairman; Robert Biglands, John Ostle, Joseph Osbome, Tom Beaty. Clerk to the Board G. Wood Turney, solicitor, Maryport. Post Office at William Edmondson's, Mawbray. -

Sweetheart Abbey and Precinct Walls Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC216 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90293) Taken into State care: 1927 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2013 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SWEETHEART ABBEY AND PRECINCT WALLS We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH SWEETHEART ABBEY SYNOPSIS Sweetheart Abbey is situated in the village of New Abbey, on the A710 6 miles south of Dumfries. The Cistercian abbey was the last to be set up in Scotland. -

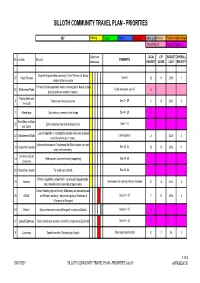

Item 09 Appendix Silloth

SILLOTH COMMUNITY TRAVEL PLAN - PRIORITIES KEY Walking Cycling Public T Car/Safety Other (n/a) Funded Transfer to other budget Linked Request Duplicate Requests Objectives LOCAL LTP BUDGET OVERALL NoLocation Request COMMENTS addressed PRIORITY SCORE COST PRIORITY Request for pedestrian crossing at Hylton Terrace for School 27 Hylton Terrace See 50 20 11 £15k 1 children & library people Primary School desperately needs crossing patrol. Needs to be a 50 Skinburness Road To be assessed - see 27 4 priority before an accident happens. Playing fields and 8 Pedestrian crossing required See 7 + 29 3 12 £12k 2 The Croft 7 After bridge Drop kerb on pavement after bridge See 8 + 29 32 Post Office and Spar 29 Zebra crossings from and to playing field. See 7 + 8 5 and Crofts Lack of footpaths. If no footpaths possible some sort of speed 32 Blitterlees to Silloth Land required 2 £20k 3 restrictions to be put in place. Continued from oppsite Tanglewood the Silloth people can walk 24 Footpath to Cemetery See 28, 44 13 12 £15k 4 safely to the cemetery. Cemetery at East 44 Path required (accidents nearly happening) See 24, 28 Causeway 28 Footpath to Cemetery To avoid early arrivals See 24, 44 Difficult negotiating wheelchairs - not enough dropped kerbs - 18 General Enforcement of existing Police & Allerdale 21 13 £10k 5 also motorists park across the dropped kerbs. Current flooding signs at Allonby & Mawbray are ignored becaus 26 B5300 are left open too long + advanced signing at Greenrow & See 33 + 47 7 9 £16k 6 Ellengrove at Maryport 33 Dubmill Sign to show when road to Maryport is closed at Dubmill. -

Tidelines Winter 2018

Issue 49 Winter 2018 Eels in the Classroom Page 4-5 Coastline Pollinators Project Page 6-7 SCRAPbook Pilots Page 10-11 Chairman’s Column Alastair McNeill FCIWEM C.WEM MCMI e live in times when there are increasing and often progressing at pace and it is pleasing to note that Coastwise competing demands on the marine environment has received considerable promotion as the result of featuring Wincluding the Solway Firth. SFP’s key aim is to on TV, newspapers and social media. The Coastwise make a significant contribution to sustainable development Facebook page had over 1900 followers at the time of the and environment protection by supporting integrated marine Board’s September meeting. The Solway Marine Information, and coastal planning. This continues to be achieved through Learning and Environment (SMILE) Project aims to identify the provision of transparent, balanced and respected gaps in existing data, will gather information and, share practices that support objective, impartial, evidence-based knowledge using innovative communications: it will update mechanisms involving cooperation and consensus. and supersede the Partnership’s Solway Review of 1996. Marine planning, resulting from an EU Directive, introduced Activities undertaken thus far are ensuring the project is well a process for maritime spatial planning on both sides of the on its way to delivering its outcomes and, subject to Solway. In Scotland, the National Marine Plan successful bids for EMFF support, will potentially sets out a framework to promote sustainable result in separate maritime socioeconomic development and the sustainable use of studies on both the north and south marine resources. Currently, three Solway coastlines. -

North West England and North Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2

North West England and North Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 North West & North Wales Coastal Group North West England and North Wales Shoreline Management Plan SMP2 Main SMP2 Document North West England and North Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 Contents Amendment Record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Issue Revision Description Date Approved by 14 th September 1 0 1st Working Draft – for PMB Review A Parsons 2009 1st October 1 1 Consultation Draft A Parsons 2009 2 0 Draft Final 9th July 2010 A Parsons Minor edits for QRG comments of 3 rd 9th September 2 1 A Parsons August 2010 2010 Minor amendment in Section 2.6 and 12 th November 2 2 A Parsons Table 3 2010 18 th February 3 0 Final A Parsons 2011 Halcrow Group Limited Burderop Park, Swindon, Wiltshire SN4 0QD Tel +44 (0)1793 812479 Fax +44 (0)1793 812089 www.halcrow.com Halcrow Group Limited has prepared this report in accordance with the instructions of their client, Blackpool Council, for their sole and specific use. Any other persons who use any information contained herein do so at their own risk. © Halcrow Group Limited 2011 North West England and North Wales Shoreline Management Plan 2 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................2 1.1 NORTH WEST ENGLAND AND NORTH WALES SHORELINE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2 ......................................... 2 1.2 THE ROLE OF THE NORTH WEST ENGLAND AND NORTH WALES SHORELINE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2......... 3 1.3 THE OBJECTIVES OF THE SHORELINE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2 ................................................................................. 5 1.4 SHORELINE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2 REPORT STRUCTURE ....................................................................................... -

The Influence of Received Pronunciation on a West Cumbrian Speaker of English Provincial Standard By- Joan Barbara Pashola

The influence of received pronunciation on a west Cumbrian speaker of English provincial standard by- Joan Barbara Pashola Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy* School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1970 ProQuest Number: 10731613 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731613 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This is a study of the influence of received pronunciation on a speaker from Workington, Cumberland, His speech is described as occtipying a position between received pronunciation and the more conservative Workington speech norm. In this regard he is contrasted with a second Workington man, of identical background, and their status as typical Workington speakex^s is established by means of a questionnaire. Attention is limited to diffex'ing phonetic realisations of the same vowel phonemes, noted impressionistically and supported by accompanying acoustic analysis. Exemplification is provided by a tape-recording of the same passage spoken by the two informants with a transcription of the passage showing linguistic innovation. -

Harris, Member of Holm Monthly Meeting, Master

Friends in Admiral Rodney's Squadron In 1781 two members of Holm Monthly Meeting, Cumberland, were impressed into the British Navy; Joseph Skelton and Jonathan Taylor were taken from the merchant ship Isabella, Anthony Harris, member of Holm Monthly Meeting, master. Their plight has recently come to light in two letters found in the archives of New York Yearly Meeting. The letter "on behalf of Joseph Skelton1' written at Wigton in 4th month 1782 is signed by eight members of Holm Monthly Meeting. TO FRIENDS IN NORTH AMERICA OR ELSEWHERE Dear Friends: Whereas our Friends Clement Skelton and Anthony Harris, have requested our Certificate, in favour of Joseph Skelton, who was impressed from his Master, Anthony Harris, at New York the loth day of the i ith month 1781, and carried on Board the King's Ship, Intrepid, Capt. Molloy, one of Admiral Rodney's Squadrent, if the above Ship should come to New York, or any way under your Notice, that you make Enquire for Jo« Skelton, and use your utmost indeavors to procure him his Liberty; or any other Assistance in your power, will much oblige your Friends and Brethern. These are to certify to you on his behalf that Clement Skelton and Anthony Harris, are both members of our Monthly Meeting, the young man Jo! Skelton had a religious and sober education with his Father, his conduct whilst here and also when under our Friend Anthony Harris, his late Master, was orderly and agreeable to Friends which Intitles him to the esteem of a member, we there fore Recommend him to your tender Notice; indeavoring if it seem practible to Obtain him Liberty from his disagreeable Confine ment, so with desire for the same, and his preservation, and Growth in the Truth, we remain your Friends and Brethern, Signed in and on behalf of the Holm Monthly Meeting held at Wigton in the County of Cumberland, the i8th of 4th month 1782.