ATA Report Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIBER Lesson Plans As of October 2020

CIBER Focus Interview Series Video Annotation Aid to Artisans Ghana Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFvnKmcCE5M Length: 17:09 Production Date/Year: July 24, 2018 Keyword Topics: Artisan, Ghana, Crafts Guest Info: Bridget Kyerematen-Darko In an interview with Jimmy Bettcher, Bridget Kyerematen-Darko discusses her work with Aid to Artisans Ghana. Darko is the Executive Director of Aid to Artisans Ghana and Bettcher is a 2012 MBA candidate at the Indiana University Kelley School of Business. Darko, who has worked at Aid to Artisans (ATA) for seventeen years, discusses the organization's mission and core activities as well as its successes and failures, noting that the global recession has adversely affected market demand. Darko also discusses her own background and how she became involved with ATA Ghana. Darko describes how ATA Ghana has changed during the past seventeen years. She discusses her long term strategy for maintaining a sustainable organization and notes the importance of having good board governance and being mindful of organizational finance. ATA Ghana has been successful at leveraging its available funds for growth, and in bridging the gap between tradition and technology to help artisans' product development process. Darko describes the challenges facing the artisan craft industry in Ghana, including performing effective market research, balancing production capabilities with market needs, and analyzing competitors. Finally, Darko offers advice to American companies interested in partnering with ATA Ghana and reflects on her collaboration with MBA student consultants at Kelley. Video Summary/Synopsis: 0:45 - Darko explains what Aid to Artisans Ghana is and what it does. -

Haitian Handicraft Value Chain Analysis

HAITIAN HANDICRAFT VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS microREPORT # 68 August 2006 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Eric Derks of Action for Enterprise with Ted Barber, Olaf Kula and Elizabeth Dalziel of ACDI/VOCA under the Accelerated Microenterprise Advancement Project – Business Development ECUAServicesDOR ECOTOURISM (AMAP: INDUSTRY BDS). S TUDY i HAITIAN HANDICRAFT VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS microREPORT # 68 DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the view of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. OBJECTIVES & METHODOLOGY 3 A. STUDY OBJECTIVES 3 B. APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 3 II. VALUE CHAIN CHARACTERISTICS 5 A. OVERVIEW 5 B. END MARKET CHANNELS 7 C. BUSINESS ENABLING ENVIRONMENT 9 D. VALUE CHAIN PARTICIPANTS & INTER-FIRM LINKAGES 10 E. SUPPORT MARKETS 15 III. FINDINGS 18 A. THE PRIORITIZAITION PROCESS 18 B. CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES 18 IV. STAKEHOLDER WORKSHOP 23 V. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR NEXT STEPS 25 ANNEX 1: SCOPE OF WORK 26 ANNEX 2: FIELD ITINERARY 28 ANNEX 3: LIST OF INTERVIEWEES 31 ANNEX 4: CONSTRAINTS & OPPORTUNITY MATRIX 35 ANNEX 5: STAKEHOLDER WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS 36 HAITIAN HANDICRAFT VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS LIST OF ACRONYMS ADPAH Association des Producteurs d’Artisanat Haïtien AMAP BDS Accelerated Microenterprise Advancement Project – Business Development Services ATA Aid to Artisans ATO Alternative -

Aid to Artisans Aid to Artisans

Aid to Artisans Aid to Artisans Summer 2016 ATA Celebrates its 40th anniversary @ NY NOW Meet the MRP Class of 2016 Canvas Home Small Grants Bring Big Hope Across the Globe Support our Artisans and Partners in Haiti 1 NY NOW August 2016 marked a significant moment for ATA as we celebrated our 40th Anniversary. Our familiar orange booth was filled with crafts from Mexico, Haiti, Nepal, Tur- key, Myanmar, Tibet, and Syrian Refugees living in Turkey. With its colorful dolls and toys, the product collection from Tibet was our bestseller. 2 Once more, Tibet’s Dropenling collection stood out by the vivid colors reflected in the handmade dolls and stuffed toys created by artisans providing sustainable, long-term solutions to the promotion and preservation of Tibetan culture. Chin-Chili’s product collection from Myanmar represented the second best seller for this edition of NY NOW. Their woven textiles, pillows, table runners, and bags were a wonderful addition to the booth. Our walls were decorated by wonderful paintings and printed stuffed toys made by women artisans from the Janakpur Wom- en Development center in Nepal. This organization was built to create sustainable solutions to support artisans, from Maithil culture. The toy collection and clutches created by Soma artisans based in Turkey gave a wonderful touch to the booth. Re- siding in the mining town of Soma, Manisa, Turkey, the Soma Artisans initiative, provides economic opportunities for women 3 in that region. Making their first appearance at NY NOW, Amal (Hope in Arabic), a newly created organization of Syrian women refugees liv- ing in Fatih, Turkey, brought beautiful and colorful embroidered jewelry and clutches inspired by memories of Syria. -

Additional Information About the U.S. Economy, Top U.S. Imports, Sector Websites, and Consumer Good Marketing

Additional Information about the U.S. Economy, Top U.S. Imports, Sector Websites, and Consumer Good Marketing 1.) U.S. Economy (2007) • GDP - $13.78 Trillion • Population – 304 million • GDP – per capita - $45,800 people • GDP – composition by sector • Labor Force – 153.1 million o Services – 79% (including unemployed) o Agriculture – 1.2% • Exports - $1.148 trillion o Industry – 19.8% • Imports $1.968 trillion 2.) Top U.S. Imports (2007) Product Share (by %) 1) Mineral fuel, oil, etc. 18.7 14) Iron/Steel Products 1.62 2) Machinery 12.8 15) Toys And Sports Equipment 1.59 3) Electrical machinery 12.7 16) Iron And Steel 1.31 4) Auto, bus & truck vehicles 11.0 17) Aircraft, Spacecraft 1.12 5) Computers & telephones 2.75 18) Salvaged & recycled goods 1.08 6) Pharmaceutical products 2.50 19) Footwear 0.99 7) Precious stones, metals 2.43 20) Rubber 0.96 8) Organic chemicals 2.31 TOTAL 100.0 9) Furniture and bedding 2.09 10) Auto parts 2.01 Source: U.S. Department of 11) Knit Apparel 1.94 Commerce, Bureau of Census 12) Woven Apparel 1.92 13) Plastic 1.76 3.) Sector-Specific Contact Information for Standards and Regulations a. Textiles and Apparel http://web.ita.doc.gov/tacgi/labeling2.nsf/ http://web.ita.doc.gov/tacgi/eamain.nsf/6e1600e39721316c852570ab0056f719/448cd661f6 48520c8525739a005a725a?OpenDocument b. Mining/Marble: National Mining Association: http://www.nma.org/ Contacts: Moya Phelleps Senior Vice President, Member Services Emily Schlect International Policy Analyst c. Jewelry: http://www.ita.doc.gov/td/ocg/jewelry.htm 1 d. -

Crafts Development and Marketing Manual. Appropriate Technologies for Development

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 289 003 CE 048 999 AUTHOR Ramsay, Caroline C.; And Others TITLE Crafts Development and Marketing Manual. Appropriate Technologies for Development. Peace Corps Information Collection & Exchange Manual Series No. M-24. INSTITUTION Williams (Walker A.) and Company, Inc., Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY Peace Corps, Washington, DC. Information Collection and Exchange Div. PUB DATE May 86 CONTRACT PC-885-1647 NOTE 256p.; Portions of appendixes contain small/marginally legible print. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; Business Administration; Craft Workers; *Developing Nations; Economic Opportunities; *Entrepreneurship; Foreign Countries; *Handicrafts; *Marketing; *Program Development; Program Implementation; Risk; *Small Businesses; Transportation; Volunteers; Volunteer Training IDENTIFIERS Botswana; Ecuador; *Peace Corps ABSTRACT This manual was developed to help Peace Corps 7olunteers assist local craftspeople in developing nations in initiating and operating small businesses to produce and market their products. The manual is organized in eight chapters that cover the following topics: the crafts environment, common problems and solutions for a crafts business, organizing and managing the crafts project, production, marketing, distribution, case studies of two crafts industries, and resource groups and marketing channels. Extensive appendixes provide information on the loan or grant application process, international trade terms and conditions, international shipping conversions, international shipping procedures, shipping and collection, documentation, methods of receiving payment, and packing requirements. A risk matrix for international terms of payment, several sample documents, a list of Peace Corps resources, and an annotated bibliography are also included. (KC) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Creating an Efficient Marketing Plan for Aid to Artisansu

Creating an Efficient Marketing Plan for Aid to ArtisansU December 16th, 2015 Authors: Ife Bell [email protected] ______________________ Anjali Kuchibhatla [email protected] ______________________ Melissa Rivera [email protected] ______________________ With contributions from: Michel Sabbagh In Cooperation With: Maud Obe, [email protected] Senior Program Coordinator, Aid to Artisans Proposal Submitted To: Professor Fred Looft, [email protected] Professor Brigitte Servatius, [email protected] Washington, D.C. Project Center This project is submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree requirements of Worcester Polytechnic Institute. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions or options of Aid to Artisans or Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Abstract This purpose of this project was to develop a marketing plan for sustainability of Aid to Artisans’ e-platform, Aid to ArtisansU. The team accomplished this by completing the following five steps: defining the mission, identifying the target audience, advertising through print and social media marketing, and finally, locating sponsors to finance it. We provided short-term and long-term recommendations to update the platform and maintain the website for future sustainability. 1 Acknowledgements We would like to thank our advisors Brigitte Servatius and Fred Looft for their advice and guidance in this project. We would also like to thank our sponsor, Maud Obe, for mentoring and teaching us about working in the nonprofit sector. We would like to extend our gratitude to everyone we worked with who helped us in the completion of our project: thank you to the entire Creative Learning and CreativeU staff for your support and helpful information! Readers interested in more information about this project should contact Professor Fred Looft or Brigitte Servatius via email at [[email protected]] and [[email protected]]. -

Aid to Artisans

AID TO ARTISANS: BUILDING PROFITABLE CRAFT BUSINESSES NOTES FROM THE FIELD NO. 4 April 2009 This publication was prepared by Aid to Artisans for the Business Growth Initiative Project and financed by the Office of Economic Growth of EGAT/USAID. This report is also available on the Business Growth Initiative project website at www.BusinessGrowthInitiative.org. AID TO ARTISANS BUILDING PROFITABLE CRAFT BUSINESSES Authored by: Marilyn Hnatow, Aid to Artisans Submitted to: USAID/EGAT/EG Contract No.: EEM-C-00-06-00022-00 April 2009 www.BusinessGrowthInitiative.org DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. The Role of Crafts in Developing Economies1 Today, in many developing nations, handcraft production is a major form of employment and in some countries constitutes a significant part of the export economy. Observers of the handcraft sector predict that the escalating number of small businesses turning to handcraft production is unlikely to decline significantly in the future. More specifically, artisans have been identified as the second largest sector of rural employment after agriculture in many regions of the world. Handcraft production crosses all sectors of the modern global economy—from pre-industrial to industrial and post-industrial. Artisan production has thrived because handcrafted products offer distinct advantages: minimal start-up capital, flexible work hours, the ability to work at home, and freedom to manage one’s own business. Unlike many other forms of labor, artisan production can also enable a degree of labor autonomy for those who have limited access to the cash economy. -

WORLD CRAFTS COUNCIL Finding Aid

WORLD CRAFTS COUNCIL Finding Aid 1964-2008 Processed by Pam Harris, ACC Library & Archives Intern Spring 2012 Series Series Subseries Box Contained Beginning Ending Scope and Content Note # Folders Year Year Range Range 1 Aileen Osborn 1A: Biographical A-1 Aileen Osborn Webb was the primary founder of the World Craft Webb Council. 1 Aileen Osborn 1A: Biographical A-1 Correspondence 1966 1966 Correspondence preceding and following the Second World Webb 1966 Congress in Montreux, Switzerland, including with Robert Hart of the U.S. Department of the Interior - includes originals, some handwritten, and carbon copies 1 Aileen Osborn 1A: Biographical A-1 1967 1967 General business correspondence, including with Carl Fox, Director Webb of Museum Shops of the Smithsonian Institution – includes originals, some handwritten, and carbon copies 1 Aileen Osborn 1A: Biographical A-1 Correspondence 1968 1968 General business correspondence and correspondence preceding Webb 1968 and following the Third World Congress in Lima Peru including with Robert Hart of the U.S. Department of the Interior - includes originals, some handwritten, and carbon copies 1 Aileen Osborn 1A: Biographical A-1 Correspondence 1969 1969 General business correspondence, including with Virginia M. Webb 1969 Wallas of the Office of the U.S. Secretary of State - includes originals, some handwritten, and carbon copies - also includes AOW's original report of her trip to Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Turkey and Greece in October, November, 1969 with short summary transmission memo to James Plaut - report includes contact information and original business cards of contacts in individual countries 1 Aileen Osborn 1A: Biographical A-1 Correspondence 1970 1970 General business correspondence , including with Robert R. -

Artisans and the Marketing of Ethnicity: Globalization, Indigenous Identity, and Nobility Principles in Micro-Enterprise Development

Artisans and the Marketing of Ethnicity: Globalization, Indigenous Identity, and Nobility Principles in Micro-Enterprise Development Robin M. Chandler, Ph.D. Northeastern University Ethnicity 2007 As a constructed category of human difference, 'ethnicity' has given way to 'culture' in its shared genealogy in the new millennium. Public knowledge about such phenomena as 'ethnic cleansing', debates on immigration, and the use of ethnicity as both a dependent and independent variable in research and policy are central realities in the domestic and foreign policies of many nations. The social psychology of group affiliation, nationalism, and the use of ethnicity (as well as gender) in workplace diversity, or the deployment of ethnicity in electoral politics continues to perplex and complicate human social interaction. One of the anomalies of culture as a way of life among 'subcultures' is the degree to which ethnic differences constrain or expand human freedom and the right of access to the benefits and resources of the planet. Globalization and transnationalism, in particular, has affected the way culture-as-difference is deployed in identity politics and the manipulation of culture in the reconstruction of societies (Yudice, 2003). Race or ethnicity is often a marker of advantage or disadvantage. Structured inequalities, over consumption, and the competition for scarce resources. Social conflict and political unrest only further exacerbate the possibilities of economic freedom for the poor and deepen the economic divide creating dimensions of stratification based on power, privilege, and prestige. Conventional social science has examined these challenges historically, but the new globalization of capitalization and increasing political tensions among governments have caused many social advocates, non-governmental organizations, and financial institutions to take their case to the micro-level in a bid to alleviate poverty through small business development -microenterprise from rural settlements to the urban centers. -

2003 Comprehensive Report on U.S. Trade and Investment Policy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa and Implementation of the African Growth and Opportunity Act

2003 COMPREHENSIVE REPORT ON U.S. TRADE AND INVESTMENT POLICY TOWARD SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AFRICAN GROWTH AND OPPORTUNITY ACT A Report Submitted by the President of the United States to the United States Congress Prepared by the Office of the United States Trade Representative THE THIRD OF EIGHT ANNUAL REPORTS MAY 2003 2003 Comprehensive Report on U.S. Trade and Investment Policy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa and Implementation of the African Growth and Opportunity Act The Third of Eight Annual Reports May 2003 Foreword ................................................................... iii I. U.S.-African Trade and Investment Highlights ..............................1 II. Executive Summary .....................................................3 III. The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) ..........................5 A. AGOA Summary, Eligibility, and Implementation .................5 B. AGOA II ..................................................11 C. Outreach ..................................................11 IV. Economic and Trade Overview ..........................................15 A. Economic Growth ..........................................15 B. Africa’s Global Trade .......................................16 C. Trade with the United States ..................................18 D. International Financing, Investment Results, and Debt ..............19 E. Economic Reforms .........................................22 F. Reforms Undertaken by AGOA Beneficiary Countries ..............23 G. Regional Economic Integration -

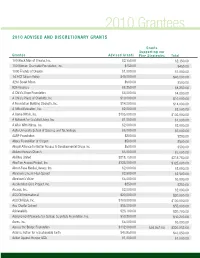

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised and Discretionary Grants

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised And discretionAry GrAnts Grants supporting our Grantee Advised Grants Five strategies total 100 Black Men of Omaha, Inc. $2,350.00 $2,350.00 100 Women Charitable Foundation, Inc. $450.00 $450.00 1000 Friends of Oregon $1,000.00 $1,000.00 1st ACT Silicon Valley $40,000.00 $40,000.00 42nd Street Moon $500.00 $500.00 826 Valencia $8,250.00 $8,250.00 A Child’s Hope Foundation $4,000.00 $4,000.00 A Child’s Place of Charlotte, Inc. $10,000.00 $10,000.00 A Foundation Building Strength, Inc. $14,000.00 $14,000.00 A Gifted Education, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 A Home Within, Inc. $105,000.00 $105,000.00 A Network for Grateful Living, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Wish With Wings, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Aalto University School of Science and Technology $6,000.00 $6,000.00 AARP Foundation $200.00 $200.00 Abbey Foundation of Oregon $500.00 $500.00 Abigail Alliance for Better Access to Developmental Drugs Inc $500.00 $500.00 Abilene Korean Church $3,000.00 $3,000.00 Abilities United $218,750.00 $218,750.00 Abortion Access Project, Inc. $325,000.00 $325,000.00 About-Face Media Literacy, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Abraham Lincoln High School $2,500.00 $2,500.00 Abraham’s Vision $5,000.00 $5,000.00 Accelerated Cure Project, Inc. $250.00 $250.00 Access, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 ACCION International $20,000.00 $20,000.00 ACCION USA, Inc. -

PDFAK507.Pdf

CONTRACT/AGREE1S'NT-, 2 Date PlO/T Received: DATA SHEET 27L26O Actioii fvonitor. PART ONE: COMPLETE EACH BLOCK FOR BOTH NEW ASSISTANCE/ACQUISITION AND MODIFICATION ACTIONS 3. Contract/Agreement Number: 1.5-IT " 4. Contractor/Recipient Name: 5. Organization Symbol: 6. Project Title: 7. Project Officer's Name: 8. Organization Symbol: 6 - ?f (..8 9. Requisitioning Organzatoe 19. Budget Document ID No: ON Plan Code: , . i 3 10. TYPE OF ACTION: f 20. Country or A. New Acquisition/Assistance Region of B. Continuation of activities set Performance: H N 1,b forth in a contractual document C. Revision of work scope/purpose 21. a. This Action Increases TEC by $ of award _ b. Total Est. Cost of 11. thisAmount of PlO/T: U.S. $ // Contractual Document S this P22. 12. Amount Pbligatedo Amount of Non Federal Funds Subobligat7e --. Pledged to the U.S. $ Deobligated by U.S. $ L tProject: this Action: 23. Effective Date 13. Cumulative U.S.$ C. of this Obation: Action: 24. Estimated 14. Thi; Action Completion/ Funded Through: $ / Z Z / Expiration 15. Date Contractual Date: / Documents Signed Z. / ", 25. Contractor byAIDOfficial: DUNS Number: I I I I I I I 16. Incrementally I 26. Consultant Funded Contract: Type Award: 17. Host Country/ 27. Number of Counterpart Inst.: Person Months: (Univ. Contracts) (PASA/RSSA only) 18. Campus 28. Number of Coordinator: Persons: (Univ. Contracts) (PASA/RSSA only) 29. Neootiator's Typed Name: 30. Negotiator's Signature: 31. Date Signed: 32. Contract/Grant Officer's 33 Conlract/Grant Officer's Signature: 34. Date Signed: Organization Symbol: t/S4lb/ 14 0e.