The Strange Case of December 4: a Liturgical Problem Arnold A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Difference Between Blessing (Bracha) and Prayer (Tefilah)

1 The Difference between Blessing (bracha) and Prayer (tefilah) What is a Bracha? On the most basic level, a bracha is a means of recognizing the good that God has given to us. As the Talmud2 states, the entire world belongs to God, who created everything, and partaking in His creation without consent would be tantamount to stealing. When we acknowledge that our food comes from God – i.e. we say a bracha – God grants us permission to partake in the world's pleasures. This fulfills the purpose of existence: To recognize God and come close to Him. Once we have been satiated, we again bless God, expressing our appreciation for what He has given us.3 So, first and foremost, a bracha is a "please" and a "thank you" to the Creator for the sustenance and pleasure He has bestowed upon us. The Midrash4 relates that Abraham's tent was pitched in the middle of an intercity highway, and open on all four sides so that any traveler was welcome to a royal feast. Inevitably, at the end of the meal, the grateful guests would want to thank Abraham. "It's not me who you should be thanking," Abraham replied. "God provides our food and sustains us moment by moment. To Him we should give thanks!" Those who balked at the idea of thanking God were offered an alternative: Pay full price for the meal. Considering the high price for a fabulous meal in the desert, Abraham succeeded in inspiring even the skeptics to "give God a try." Source of All Blessing Yet the essence of a bracha goes beyond mere manners. -

The Land of Israel's Loyalty to the Jewish People

The Land of Israel’s Loyalty to the Jewish People by Rabbi Chaim Jachter As Parashat Behukotai and the book of Vayikra draw to a close, Hashem delivers a stinging rebuke and warning to our people. This rebuke, known as the Tochahah is the first of two such rebukes in the Humash (the second being towards the end of Sefer Devarim). This section contains a series of frighteningly prophetic descriptions of the tragedies that will befall the nation should they fail to follow God’s ways. Indeed, so frightening is this Tochachah that Torah is read this section in a lower voice. There are even some synagogues where the rabbi or Torah reader is called for the Aliyah that contains the Tochachah, as some would rather avoid being called for this Aliyah. In the midst of the very dark cloud of these warnings of punishment and exile in Parashat Behukotai we find a silver lining. The Torah promises (Vayikra 26:32) that after our people will be exiled from our land, our enemies will fail in their endeavors to settle the land. Ramban, writing in the twelfth century, notes that this is an extraordinary promise to us as there is no other place on earth that at one time was settled, lush and fertile but is now utterly desolate and destroyed. He observes that this promise has most obviously been fulfilled in that from the time we left our land, it has not accepted any other nation, despite their many efforts to develop the land. Indeed, the Romans, Arabs, Crusaders and Ottomans failed miserably in their efforts to settle the land of Israel. -

To Wear Is Human: Parshat Ki Teitze by Rabbi Elliot Kukla and Reuben Zellman, 2006

To Wear Is Human: Parshat Ki Teitze by Rabbi Elliot Kukla and Reuben Zellman, 2006 For all those who have ever struggled with how to discipline children’s bad behavior, this week’s parsha, Ki-Teitze, off ers an easy answer: stone them to death! (Deut. 21:21) Th ankfully, Jews have recognized for over a thousand years that this is an unacceptable solution to a common problem. In fact, we learn in the Talmud (Sanhedrin 71a) that this apparent commandment of the Torah was never once carried out. Our Sages refused to understand this verse literally, as it confl icted with their understanding of the holiness of each and every human life. With this scenario in mind, let us look at another verse in our parsha: “A man’s clothes should not be on a woman, and a man should not wear the apparel of a woman; for anyone who does these things, it is an abomination before God.” (Deut. 22:5) Just as classical Jewish scholars reinterpreted the commandment to stone to death rebellious children, they also read our portion’s apparent ban on “cross-dressing” to yield a much narrower prohibition. Th e great medieval commentator Rashi explains that this verse is not simply forbidding wearing the clothes of the “opposite gender.” Rashi writes that such dress is prohibited only when it will lead to adultery. Maimonides, a 12th century codifi er of Jewish law, claims that this verse is actually intended to prohibit cross-dressing for the purposes of idol worship. (Sefer haMitzvot, Lo Taaseh 39-40) In other words, according to the classical scholars of our tradition, wearing clothes of “the wrong gender” is proscribed only when it is for the express purpose of causing harm to our relationship with our loved ones or with God. -

Dear Torah Tidbits Family

DEAR TORAH TIDBITS FAMILY Rabbi Avi Berman sions someone can make. Yet, we can’t Executive Director, take it for granted or judge those who are OU Israel not rushing to come. We recognize that this is not an easy decision. Yom HaAliyah, which took place this past Sunday, was established The second beautiful aspect of Yom to acknowledge the necessity and impor- HaAliyah is that it serves as a reminder tance of Aliyah to the State of Israel and to to those of us who made Aliyah to identify celebrate the incredible contributions of people in our lives whose Aliyah we can Olim to our Homeland. These are import- help. Whether it be a new neighbor who ant, but I think what is equally, perhaps needs help understanding their electric more important, is for us olim to remind bill, a kid in our child’s class who could use ourselves of our personal Aliyah journeys, a playdate (pending corona guidelines), or thank those who helped us, and reflect on someone we meet at the grocery store who the people in our lives whom we can help could use a smile and a few kind words. It to successfully make Aliyah. I cannot men- might be friends living abroad who have tion my Aliyah without thanking my par- questions about life in Israel. Personally, ents from the bottom of my heart for bring- over the past half a year I have received ing my siblings and I when I was nine. many more inquiries than usual from pro- spective olim who have questions about Most olim I know say that Aliyah is the how their kids will adjust, looking for a job, best decision they ever made (perhaps or curious about the community we live in, second to marrying their spouse), but they Givat Ze’ev, or other communities. -

Whats Good Events Guide December 5-8 2019 Gainesville and Alachua

WHAT’S GOOD. ALACHUA | ARCHER | GAINESVILLE | HAWTHORNE | HIGH SPRINGS | LA CROSSE | MICANOPY | NEWBERRY | WALDO Plan your weekend with the official events guide from Visit Gainesville, Alachua County December 5-8, 2019 Enjoy a Magical Holiday Theatrical Performance for the Entire Family at Spirit of the Horse Friday, December 6 – Saturday, December 7, 7 p.m. – 9 p.m., Sunday, December 8, 6 p.m. – 8 p.m. | Alachua County Agriculture and Equestrian Center 23100 W Newberry Rd., Newberry, FL 32669 Experience an inspiring holiday story that is sure to delight and entertain. This show is in its tenth year, enjoyed by audiences around the country, and 2019 marks the premiere of Spirit of the Horse in Florida. Admission is FREE FOR VETERANS with valid ID. Food available from BubbaQue’s BBQ. Browse Unique Gifts from More Than 200 Vendors at the 51st Annual Craft Festival Saturday, December 7 – Sunday, December 8, 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. | O’Connell Center 250 Gale Lemerand Dr., Gainesville, FL 32611 Find something special for yourself or that hard to shop for person in your life. The festival has been a holiday tradition for the past 51 years and is the largest indoor craft fair in North Central Florida. Watch Santa Arrive by Helicopter at Operation Santa Delivery Saturday, December 7, 10 a.m. – 1 p.m. | Santa Fe College North Field 3700 NW 91st St., Gainesville, FL 32606 Santa will visit Gainesville not by reindeer and sleigh, but by helicopter. Enjoy games, music, food and fun activities. Helicopter Photo by the Gainesville Sun. -

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina Abstract The Roman calendar was first developed as a lunar | 290 calendar, so it was difficult for the Romans to reconcile this with the natural solar year. In 45 BC, Julius Caesar reformed the calendar, creating a solar year of 365 days with leap years every four years. This article explains the process by which the Roman calendar evolved and argues that the reason February has 28 days is that Caesar did not want to interfere with religious festivals that occurred in February. Beginning as a lunar calendar, the Romans developed a lunisolar system that tried to reconcile lunar months with the solar year, with the unfortunate result that the calendar was often inaccurate by up to four months. Caesar fixed this by changing the lengths of most months, but made no change to February because of the tradition of intercalation, which the article explains, and because of festivals that were celebrated in February that were connected to the Roman New Year, which had originally been on March 1. Introduction The reason why February has 28 days in the modern calendar is that Caesar did not want to interfere with festivals that honored the dead, some of which were Past Imperfect 15 (2009) | © | ISSN 1711-053X | eISSN 1718-4487 connected to the position of the Roman New Year. In the earliest calendars of the Roman Republic, the year began on March 1, because the consuls, after whom the year was named, began their years in office on the Ides of March. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Introduction of Rabbi Yosef Kapach to His Edition of Moses Maimonides

Introduction of Rabbi Yosef Kapach to his edition of Moses Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah (translated by Michael J. Bohnen) Rabbi Kapach was the foremost editor of the works of Maimonides. Born in Yemen in 1917, he used ancient manuscripts to restore the text of the Mishneh Torah. Several fascinating articles about Rabbi Kapach can be found at www.chayas.com/rabbi.htm The following is a summary and translation of his 20 page Introduction to his edition of the Mishneh Torah. Translator’s Summary My Work. When in my youth I studied the Mishneh Torah with my grandfather of blessed memory, most people used printed books, each with his own edition, but my grandfather and several of the others had manuscripts which were several hundred years old, each scroll of a different age. The errors and deficiencies of the printed texts were well known. The changes that Maimonides made over time in the Commentary on the Mishnah, after completing the Mishneh Torah, he then inserted in the Mishnah Torah. These are all found in our manuscripts, but some are not found in the printed texts. The Jews of Yemen are a conservative group. They would never have presumed to "correct" or "amend" a text that came into their hands, and certainly not the works of Maimonides. However, the Mishneh Torah was subjected to severe editing by the printers and various editors who made emendations of style, language, the structure of sentences and the division of halachot, to the extent that there is hardly any halacha that has not been emended. In this edition of ours, we are publishing, with God’s help, the words of Maimonides in full as we received them from his blessed hand. -

“Cliff Notes” 2021-2022 5781-5782

Jewish Day School “Cliff Notes” 2021-2022 5781-5782 A quick run-down with need-to-know info on: • Jewish holidays • Jewish language • Jewish terms related to prayer service SOURCES WE ACKNOWLEDGE THAT THE INFORMATION FOR THIS BOOKLET WAS TAKEN FROM: • www.interfaithfamily.com • Living a Jewish Life by Anita Diamant with Howard Cooper FOR MORE LEARNING, YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN THE FOLLOWING RESOURCES: • www.reformjudaism.org • www.myjewishlearning.com • Jewish Literacy by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin • The Jewish Book of Why by Alfred J. Kolatch • The Jewish Home by Daniel B. Syme • Judaism for Dummies by Rabbi Ted Falcon and David Blatner Table of Contents ABOUT THE CALENDAR 5 JEWISH HOLIDAYS Rosh haShanah 6 Yom Kippur 7 Sukkot 8 Simchat Torah 9 Chanukah 10 Tu B’Shevat 11 Purim 12 Pesach (Passover) 13 Yom haShoah 14 Yom haAtzmaut 15 Shavuot 16 Tisha B’Av 17 Shabbat 18 TERMS TO KNOW A TO Z 20 About the calendar... JEWISH TIME- For over 2,000 years, Jews have juggled two calendars. According to the secular calendar, the date changes at midnight, the week begins on Sunday, and the year starts in the winter. According to the Hebrew calendar, the day begins at sunset, the week begins on Saturday night, and the new year is celebrated in the fall. The secular, or Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar, based on the fact that it takes 365.25 days for the earth to circle the sun. With only 365 days in a year, after four years an extra day is added to February and there is a leap year. -

Early Dance Division Calendar 17-18

Early Dance Division 2017-2018 Session 1 September 9 – November 3 Monday Classes Tuesday Classes September 11 Class September 12 Class September 18 Class September 19 Class September 25 Class September 26 Class October 2 Class October 3 Class October 9 Class October 10 Class October 16 Class October 17 Class October 23 Class October 24 Class October 30 Last Class October 31 Last Class Wednesday Classes Thursday Classes September 13 Class September 14 Class September 20 Class September 21* Class September 27 Class September 28 Class October 4 Class October 5 Class October 11 Class October 12 Class October 18 Class October 19 Class October 25 Class October 26 Class November 1 Last Class November 2 Last Class Saturday Classes Sunday Classes September 9 Class September 10 Class September 16 Class September 17 Class September 23 Class September 24 Class September 30* Class October 1 Class October 7 Class October 8 Class October 14 Class October 15 Class October 21 Class October 22 Class October 28 Last Class October 29 Last Class *Absences due to the holiday will be granted an additional make-up class. Early Dance Division 2017-2018 Session 2 November 4 – January 22 Monday Classes Tuesday Classes November 6 Class November 7 Class November 13 Class November 14 Class November 20 No Class November 21 No Class November 27 Class November 28 Class December 4 Class December 5 Class December 11 Class December 12 Class December 18 Class December 19 Class December 25 No Class December 26 No Class January 1 No Class January 2 No Class January 8 Class -

Peoria Unified School District 6-Day Rotation Schedule

Peoria Unified School District 2020 – 2021 School Year Six-Day Rotation Schedule August 2020 January 2021 Day 1: August 17, 19 AM, 26 PM and 27 Day 1: January 6 PM, 11 and 22 Day 2: August 18 and 28 Day 2: January 12, 13 AM, 20 PM and 25 Day 3: August 23 and 31 Day 3: January 4, 14, 26 and 27 AM Day 4: August 21 Day 4: January 5, 15 and 28 Day 5: August 24 Day 5: January 7, 19 and 29 Day 6: August 25 Day 6: January 8 and 21 September 2020 February 2021 Day 1: September 8, 18 and 29 Day 1: February 2, 12 and 25 Day 2: September 2 AM, 9 PM, and 21 Day 2: February 4, 16 and 26 Day 3: September 11, 16 AM and 23 PM Day 3: February 3 PM, 5 and 18 Day 4: September 1, 14, 24 and 30 AM Day 4: February 8, 10 AM, 17 PM and 19 Day 5: September 3, 15 and 25 Day 5: February 9, 22 and 24 AM Day 6: September 4, 17 and 28 Day 6: February 1, 11 and 23 October 2020 March 2021 Day 1: October 9 and 22 Day 1: March 8, 25 and 31 AM Day 2: October 1, 13 and 23 Day 2: March 9 and 26 Day 3: October 2, 15 and 26 Day 3: March 1, 11 and 29 Day 4: October 5, 7 PM, 16 and 27 Day 4: March 2, 12 and 30 Day 5: October 6, 14 AM, 21 PM and 29 Day 5: March 3 PM, 4 and 22 Day 6: October 8, 20, 28 AM and 30 Day 6: March 5, 10 AM, 23 and 24 PM November 2020 April 2021 Day 1: November 2, 12 and 20 Day 1: April 5, 7 PM, 15 and 27 Day 2: November 3, 13 and 30 Day 2: April 6, 14 AM, 16, 21 PM and 29 Day 3: November 5 and 16 Day 3: April 8, 19, 28 AM and 30 Day 4: November 6 and 17 Day 4: April 9 and 20 Day 5: November 9 and 18 Day 5: April 1, 12 and 22 Day 6: November 4 PM, 10 and 19 Day 6: April 2, 13 and 26 December 2020 May 2021 Day 1: December 7, 15 and 16 AM Day 1: May 7 and 18 Day 2: December 8 and 17 Day 2: May 10 and 19 Day 3: December 1 and 9 Day 3: May 5 PM, 11 and 20 Day 4: December 2 and 10 Day 4: May 3, 12 AM, 13 Day 5: December 3 and 11 Day 5: May 4 and 14 Day 6: December 4 and 14 Day 6: May 6 and 17 EARLY RELEASE or MODIFIED WEDNESDAY • Elementary schools starting at 8 a.m. -

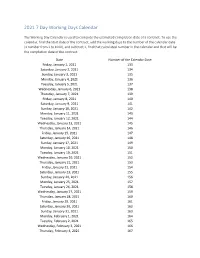

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February