A Thesis Entitled Rethinking Relationships: a Critique of the Concept of Progress by Anandi Gandhi Submitted to the Graduate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Yorker Editor David Remnick Responds to Vandana Shiva Criticism of Michael Specter’S Profile | Genetic Literacy Project

11/7/2014 New Yorker editor David Remnick responds to Vandana Shiva criticism of Michael Specter’s profile | Genetic Literacy Project Subscribe to Our Daily or Weekly Newsletter Follow 515 Like 6.9k Follow 2,778 followers Enter Your Email Address → Search About Human Agriculture Biotech Gallery Gene-ius Resources Browse Select Language ▼ New Yorker editor David Remnick responds to Browse By Related Articles Authors Vandana Shiva Vandana Shiva criticism of Michael Specter’s Tags scandal deepens, as Sources Beloit College profile or try our Advanced Search botches response to David Remnick | September 2, 2014 | New Yorker criticism More from this Source 1.9K 598 86 47 Who's who? 'David New Yorker and Goliath' roles mixed up in West In the August 18, 2014 The How Vietnam War vets aid in brain Australian Marsh v research Baxter case New Yorker magazine, in Immunotherapy represents an “Seeds of Doubt,” Michael entirely new strategy for cancer treatments European Network Specter profiled the work of the Michael Specter discusses his of Scientists for environmental activist Vandana profile of Vandana Shiva Social and Don't need much sleep? Thank your Environmental Shiva, who for many years has genes. Responsibility led a campaign against Most GMO label supporters don't (ENSSER) really support 'right to know' genetically modified crops. Vandana Shiva by Michael Specter: Vandana Shiva by Demagogue or visionary? Michael Specter: Feminist group struggles with Demagogue or On August 26, Vandana Shiva defining 'woman,' accusations of visionary? responded with a scathing transphobia Is susceptibility to procrastination rebuttal, posting “SEEDS OF genetic? Should Science and One family, one kid with a one-of-a- TRUTH–A RESPONSE TO Nature run kind disease advertorial by wacky THE NEW YORKER” on her website, commenting: What neuroscience can tell us about Dr. -

Vandana Shiva Y La Relevancia Del Feminismo Tradicional

Portland State University PDXScholar International & Global Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations International & Global Studies 11-2014 El Reto de Una Democracia Planetaria: Vandana Shiva y la Relevancia del Feminismo Tradicional Priya Kapoor Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/is_fac Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post- Colonial Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Kappor, Priya. (2014). El Reto de Una Democracia Planetaria: Vandana Shiva y la Relevancia del Feminismo Tradicional. Mediaciones, vol. 10, no. 13, pages This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in International & Global Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. MEDIACIONES #13 ELEL RETO RETO DE DEEL RETO UNA UNA DE UNA DEMOCRACIADEMOCRACIA PLANETARIA: DEMOCRACIAVANDANA SHIVA Y LA PLANETARIA:PLANETARIA:RELEVANCIA DEL FEMINISMO VANDANATRANSNACIONAL SHIVA VANDANATHE CHALLENGE SHIVA OF AN EARTH DEMOCRACY: VANDANA SHIVA AND THE YY LA LA RELEVANCIA RELEVANCIARELEVANCE OF TRANSNATIONAL FEMINISM [ PRIYA KAPOOR ] Ph.D. del College of Communication, Ohio University. M.P.S. DELen Communication, CornellFEMINISMO University. Profesora asociada de DELEstudios FEMINISMO internacionales en Portland State University. Enseña comunicación intercultural, teoría y cultura críticas, y género, raza y clase en los medios. Investiga los movimientos populares de Asia del Sur, los medios críticos, las formas culturales transnacionales, las praxis feministas y las articulaciones de TRANSNACIONALuna identidad cosmopolita. -

Earth Democracy: Justice, Sustainability, and Peace

UCLA Electronic Green Journal Title Earth Democracy: Justice, Sustainability, and Peace Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1sn052vq Journal Electronic Green Journal, 1(23) Author Anderson, Byron Publication Date 2006 DOI 10.5070/G312310651 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Review: Earth Democracy: Justice, Sustainability, and Peace By Vandana Shiva Reviewed by Byron Anderson Northern Illinois University, USA ..................................... Vandana Shiva. Earth Democracy: Justice, Sustainability, and Peace. Cambridge, MA: Southend Press, 2005. 207 pp. ISBN: 0-89608-745-X (paper), 0-89608-746-8 (cloth) US$15.00, $40.00. Acid-free, recycled paper. Earth Democracy is a movement that “prioritizes people and nature above commerce and profits” (p. 82). Earth Democracy as a phrase is defined a number of times in the book. A full definition is found in “10 Principles of Earth Democracy” (p. 9-11) covering from item one, “All species, peoples, and cultures have intrinsic worth,” to ten, “Earth Democracy globalizes peace, care, and compassion.” These principles represent a broad sweeping alternative view of a kinder more compassionate future. Earth Democracy builds on previous movements and thinkers, particularly Ghandi. The author is a writer, speaker, activist, environmentalist, physicist, and director of India’s Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology, an institute that promotes farmers’ rights, the preservation of agricultural diversity, and freedom of agriculture from multinational seed corporations. These themes are found throughout the book. She is author of many books, including Water Wars: Privatization, Pollution and Profit (2002). The book contains numerous examples, perhaps no more than small starts, of changes that have led to Earth Democracy. -

New Yosc Newsletter

!""#$%#&'()*""#$# Year of Social Change fall 2009-Spring 2010 Inspiring Enabling & Empowering Community Transformations FA 2009 - SP 2010! Faculty Organizers: Dr. Ishita Sinha Roy & Dr. Emily Yochim Michael Pollan, “The Kathy Eldon’s Creative Greg Mortenson on “Promoting Peace through Education” (Oct. 7, Sun Food Activism Project Workshop Agenda” (Feb. 25, 2010) (Sept. 25, 2009) 2009) Connects the dots Read about how Kathy uses between food and health her son Dan Eldon’s legacy to Dr. Vandana Shiva on Food Security in a Time of Climate (personal as well as inspire young people to use Change (Oct. 26, 2009) environmental), and their creative resources to introduces us to some of Environmental activist Dr. Shiva on the perils of fossil fuel inspire change the visionaries who are dependence, climate change, and the privatization of natural A unique lesson on global citizenship “re-solarizing” the food Page 9 resources like water, soil, and seeds. Pp 11-12 and the power of pennies to build the system future of young people across the Page 27 world, and foster public diplomacy Page 10 AND MANY MORE DETAILS INSIDE..... A Vision for Change “We will define new and compelling ways to inspire our students to set their extraordinary talents to the timeless values of citizenship – values grounded in a deep sensitivity to the dignity of the individual…an ambition leavened by humility, a love of country animated by the pursuit of justice Allegheny College President and a dedication to service that is framed by the James H. Mullen, Jr. awareness of something larger than themselves.” Our sincere thanks to ASG, and the Year of Social Change student ambassadors for their initiative & hard work in making this year a success. -

Vandana Shiva Is Mother Earth

Vandana Shiva is Mother Earth “As a human being, you are duty-bound to get engaged. When you find injustice, when you find unfairness, when you find untruth. But you have to get engaged knowing that you have no control over the outcome.” SUBJECT There are forces of nature, and then there is Vandana Shiva. Hers is a name Vandana Shiva close to the lips of anybody engaged in questions of sustainable agriculture, of social justice, of globalisation, of any of the great sociocultural fights of the OCCUPATION past couple of decades. Wherever there is a pulpit, where there is land and Radical Scientist tradition to protect, she’ll be there. She is loved or she is loathed, depending on who you talk to, but she is clearly a woman with a mission—to fight the rise INTERVIEWER of Big Agriculture, and the end of biodiversity. Patrick Pittman Born in 1952 in India’s Dehradun Valley, in the Uttarakhand state at the foothills PHotoGRAPHER of the Himalayas, Vandana didn’t start out intending to be an activist, or an Gauri Gill environmental warrior, or an eco-feminist, or a thorn in the side of global finance and trade. She started out in quantum physics, something her school didn’t LOCATION even teach, but which she taught herself well enough to eventually study for a New Delhi PhD in Canada. Somewhere in there, she met the tree huggers of the Chipko movement in the forests of Uttarakhand, the forests her father worked when DAte she was a child, and it became clear that a life other than the one she intended July 2012 lay in front of her. -

Empowering Women- Vandana Shiva Vandana Shiva Is an Indian Scholar

Empowering Women- Vandana Shiva Vandana Shiva is an Indian scholar, environmental activist, food sovereignty advocate, and anti-globalization author. Shiva, currently based in Delhi, has authored more than twenty books. In the essay “Empowering Women” she talks about the impact of reduction in the participation of women in agricultural and economic activities. She takes the case of Punjabi women and says that the state is the “bread basket” of India and the foci of the green revolution, yet the farmers commit suicide as they are debt- ridden without the means to repay it. The loss of biodiversity, with the major shift in agricultural pattern delimiting the crops to wheat and rice, and the immense percolation of the chemical pesticides and fertilizers into the agricultural cycle has led to desertification, barrenness of land and poverty for the farmers. According to Shiva, the women have been most hit as their reduced participation in the agricultural activities has also added to their reduced status in society and devaluation. Consequently, the sex ratio has been immensely disbalanced due to increasing number of female feticides. The women have now become an economic burden as they no longer are able to lend a helping hand in the farming. Shiva laments the loss of the ancient agricultural systems which were more women centric and profitable because, “Food systems evolved by women, based on biodiversity- based production rather than chemical based production produce hundreds of times more food, with better nutrition, quality and taste.” She makes a strong case to adopt women friendly alternatives to farming rather than the ones suggested by government bodies, as women have the capacity to eradicate hunger completely. -

Core II Social Thought and Political Economy 392 H Tu / Thu 2:303:45

Core II Social Thought and Political Economy 392 H Tu / Thu 2:303:45, Bartlett 205 Fall 2016 Instructor: Shakuntala Ray Office Hours: Tuesdays 4:005:00 at E30 Machmer, or by appointment. Email : [email protected] Course Description This course is the second seminar in the year long STPEC Core Seminar sequence. In Core I, we focused on the reading, critique, and discussion of key foundational Western texts from the 16th century onwards to explore the driving forces behind the production of modernity as a Western episteme ( the way we organize and learn the world today). In Core II, we will turn to understanding in more detail the complex ways in which key political, social, and cultural practices and philosophies of the 20th century reveal or critique contradictions, complexities and pitfalls of modernity. As this is an interdisciplinary class, we will be bringing tools and perspectives from various disciplines (i.e. economy, sociology, anthropology, political science, literary theory, gender studies, history and cultural studies) to bear upon each other, always paying special attention to the construction and reception of ideas in specific contexts differentiated by class, race, gender, sexuality, religion, and geopolitics. Importantly, we will try to understand the relevance of “theory” to praxis and the contested worlds that we all form a part. Core II is an interactive seminar rather than a lecture course. Full and active participation is needed and expected. All students are expected to attend all class meetings, arrive on time, read assigned texts, and participate in discussions. Student Responsibilities All readings and a copy of this syllabus are updated on Moodle. -

Vandana Shiva

Key Concepts: Eco-Feminism Vandana Shiva Key Work: Staying Alive – Women, Ecology, and Is Climate Change a ‘Man-made’ problem with a Feminist Solution? Development (1999), Soil Not Oil (2008), Water Wars (2002), The Violence of the Green Revolution. “The worldwide destruction of the feminine knowledge of agriculture evolved over four to five thousand years by a handful of white male scientists in less than two decades has not merely violated women as experts but, … has gone hand in hand with the ecological destruction of nature’s processes and the economic destruction of poor people in rural areas.” ”Staying Alive”, P. 8. Background: The ‘Green’ Revolution Shiva argues against this development in her book “Violence and the Green Revolution” She wants to understand what she calls the “Ecology of Terrorism”, where she links the growth of international terrorism From the late 1950s and 60s there was a major change with changes in ecological practices. She summarizes them into 3 lessons: in the way food was produced. Instead of relying on 1. Nondemocratic economic systems that centralize control over decision making and resources and displace people traditional framing methods, the Green Revolution from productive employment and livelihoods create a culture of insecurity. (Link to Eriksen) brought Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO seeds 2. Destruction of resource rights and erosion of democratic control of natural resources, the economy, & means such as ‘Dwarf Wheat’ and “IR8 Rice”). This undermines cultural identity, where one is in competition with the “other” over scarce resources. (Marx and Said) significantly higher “yields”, but were dependent on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, mechanization 3. -

Talking Trash: Oral Histories of Food In/Security from the Margins of a Dumpster By: Rachel A

Talking Trash: Oral Histories of Food In/Security from the Margins of a Dumpster By: Rachel A. Vaughn Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Sherrie Tucker ________________________________ Dr Tanya Hart ________________________________ Dr. Sheyda Jahanbani ______________________________ Dr. Phaedra Pezzullo ________________________________ Dr. Ann Schofield Date Defended: Friday, December 2, 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Rachel A. Vaughn certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Talking Trash: Oral Histories of Food In/Security from the Margins of a Dumpster ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Sherrie Tucker Date approved: December, 2, 2011 ii Abstract This dissertation explores oral histories with dumpster divers of varying food security levels. The project draws from 15 oral history interviews selected from an 18-interview collection conducted between Spring 2008 and Summer 2010. Interviewees self-identified as divers; varied in economic, gender, sexual, and ethnic identity; and ranged in age from 18-64 years. To supplement this modest number of interviews, I also conducted 52 surveys in Summer 2010. I interview divers as theorists in their own right, and engage the specific ways in which the divers identify and construct their food choice actions in terms of individual food security and broader ecological implications of trash both as a food source and as an international residue of production, trade, consumption, and waste policy. This research raises inquiries into the gender, racial, and class dynamics of food policy, informal food economies, common pool resource usage, and embodied histories of public health and sanitation. -

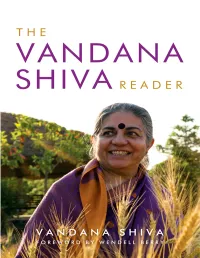

The Vandana Shiva Reader.Pdf

The Vandana Shiva Reader THE VANDANA SHIVA READER VANDANA SHIVA Foreword by WENDELL BERRY Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results. Copyright © 2014 by Vandana Shiva Foreword copyright © 2014 by Wendell Berry Published by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Figures by Dick Gilbreath Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shiva, Vandana, author. The Vandana Shiva reader / Vandana Shiva ; foreword by Wendell Berry. pages cm. — (Culture of the land) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8131-4560-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8131-5329-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8131-4699-7 (pdf : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8131-4698-0 (epub : alk. paper) 1. Shiva, Vandana. 2. Agricultural literature. I. Title. II. Series: Culture of the land. S494.5.A39S45 2015 630—dc23 2014043937 This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. Manufactured in the United States of America. -

Limiting Resource Use in Rich Economies: in the Path to De-Growth

Limiting resource use in rich economies: in the path to de-growth 2nd November 2010 LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE An oil based model LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE An oil based model • World population:6700 mill. More than 50% in cities • Industrial, urban and motorized world (80% fosil, 40% oil) • 3 main challenges: • peak oil •feeding people •Climate change • Domino effect on rest of resources LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE An oil based model •No viable massive energetic alternatives •Motorized mobility/ Industrialized agriculture • Era of compulsory degrowth •Conclusions: •We are going to move to post-oil society (how will it need to be? Low energy consumption, renewables, less urbanized, less hierarchical, less populated, living rural world,…. LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE Resource use in the world LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE RESOURCE USE IN THE WORLD •1961 self dependency/2030 two planets • Ecological footprint presently over 30% •Rich economies: per cap. Increase on 76% (1961-2005) •Increasing population 9000 mill in 2050/uneven consumption • Ecological capacity of the planet overshoot: suicide trend to increase population and per capita footprint LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE RESOURCE USE IN THE WORLD Source: Living Planet report, WWF 2010 LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE RESOURCE USE IN THE WORLD Example: Fishing stocks collapsed in 90% in 2050!!!!!!!!!!!! LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE Imports Mass of Rich Economies from South economies Rich economies Southern economies Source: A fair future. Intermon-Oxfam, 2007 LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE Resource use in Europe LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE RESOURCE USE IN EUROPE •Footprint 4,7Ha/per cap. Biocapacity 2,2 • EU net importer LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE RESOURCE USE IN EUROPE •Composition of European TMR LIMITING OUR RESOURCE USE RESOURCE USE IN EUROPE • Increased TMR Source: EEA, Europe’s environment. -

Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Development

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 7 Article 29 Aug-2019 Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Development. Vandana Shiva. North Atlantic Books, 2016 (Reprint Edition), 244 pages. ISBN 978-1-62317-051-6 Chittaranjan Subudhi Keyoor K Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Subudhi, Chittaranjan and K, Keyoor (2019). Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Development. Vandana Shiva. North Atlantic Books, 2016 (Reprint Edition), 244 pages. ISBN 978-1-62317-051-6. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(7), 428-429. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss7/29 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Development. Vandana Shiva. North Atlantic Books, 2016 (Reprint Edition), 244 pages. ISBN 978-1-62317-051-6 By Keyoor1 and Chittaranjan Subudhi2 What defines the process of development highly discussed and debated topic in the contemporary era. Vandana Shiva’s book Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Development is a contribution to this discourse. Shiva evaluates consumerism and the reductionist science of modern Western scientific framing and posits the need for feminine-principle based development, which is non-violent, non-gendered and inclusive in its primordial form.