A Lie Connection Between Hamiltonian and Lagrangian Optics Alex J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AN INTRODUCTION to LAGRANGIAN MECHANICS Alain

AN INTRODUCTION TO LAGRANGIAN MECHANICS Alain J. Brizard Department of Chemistry and Physics Saint Michael’s College, Colchester, VT 05439 July 7, 2007 i Preface The original purpose of the present lecture notes on Classical Mechanics was to sup- plement the standard undergraduate textbooks (such as Marion and Thorton’s Classical Dynamics of Particles and Systems) normally used for an intermediate course in Classi- cal Mechanics by inserting a more general and rigorous introduction to Lagrangian and Hamiltonian methods suitable for undergraduate physics students at sophomore and ju- nior levels. The outcome of this effort is that the lecture notes are now meant to provide a self-consistent introduction to Classical Mechanics without the need of any additional material. It is expected that students taking this course will have had a one-year calculus-based introductory physics course followed by a one-semester course in Modern Physics. Ideally, students should have completed their three-semester calculus sequence by the time they enroll in this course and, perhaps, have taken a course in ordinary differential equations. On the other hand, this course should be taken before a rigorous course in Quantum Mechanics in order to provide students with a sound historical perspective involving the connection between Classical Physics and Quantum Physics. Hence, the second semester of the sophomore year or the fall semester of the junior year provide a perfect niche for this course. The structure of the lecture notes presented here is based on achieving several goals. As a first goal, I originally wanted to model these notes after the wonderful monograph of Landau and Lifschitz on Mechanics, which is often thought to be too concise for most undergraduate students. -

Fermat's Principle and the Geometric Mechanics of Ray

Fermat’s Principle and the Geometric Mechanics of Ray Optics Summer School Lectures, Fields Institute, Toronto, July 2012 Darryl D Holm Imperial College London [email protected] http://www.ma.ic.ac.uk/~dholm/ Texts for the course include: Geometric Mechanics I: Dynamics and Symmetry, & II: Rotating, Translating and Rolling, by DD Holm, World Scientific: Imperial College Press, Singapore, Second edition (2011). ISBN 978-1-84816-195-5 and ISBN 978-1-84816-155-9. Geometric Mechanics and Symmetry: From Finite to Infinite Dimensions, by DD Holm,T Schmah and C Stoica. Oxford University Press, (2009). ISBN 978-0-19-921290-3 Introduction to Mechanics and Symmetry, by J. E. Marsden and T. S. Ratiu Texts in Applied Mathematics, Vol. 75. New York: Springer-Verlag (1994). 1 GeometricMechanicsofFermatRayOptics DDHolm FieldsInstitute,Toronto,July2012 2 Contents 1 Mathematical setting 5 2 Fermat’s principle 8 2.1 Three-dimensional eikonal equation . 10 2.2 Three-dimensional Huygens wave fronts . 17 2.3 Eikonal equation for axial ray optics . 23 2.4 The eikonal equation for mirages . 29 2.5 Paraxial optics and classical mechanics . 32 3 Lecture 2: Hamiltonian formulation of axial ray optics 34 3.1 Geometry, phase space and the ray path . 36 3.2 Legendre transformation . 39 4 Hamiltonian form of optical transmission 42 4.1 Translation-invariant media . 49 4.2 Axisymmetric, translation-invariant materials . 50 4.3 Hamiltonian optics in polar coordinates . 53 4.4 Geometric phase for Fermat’s principle . 56 4.5 Skewness . 58 4.6 Lagrange invariant: Poisson bracket relations . 63 GeometricMechanicsofFermatRayOptics DDHolm FieldsInstitute,Toronto,July2012 3 5 Axisymmetric invariant coordinates 69 6 Geometry of invariant coordinates 73 6.1 Flows of Hamiltonian vector fields . -

Schrödinger's Argument.Pdf

SCHRÖDINGER’S TRAIN OF THOUGHT Nicholas Wheeler, Reed College Physics Department April 2006 Introduction. David Griffiths, in his Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (2nd edition, 2005), is content—at equation (1.1) on page 1—to pull (a typical instance of) the Schr¨odinger equation 2 2 i ∂Ψ = − ∂ Ψ + V Ψ ∂t 2m ∂x2 out of his hat, and then to proceed directly to book-length discussion of its interpretation and illustrative physical ramifications. I remarked when I wrote that equation on the blackboard for the first time that in a course of my own design I would feel an obligation to try to encapsulate the train of thought that led Schr¨odinger to his equation (1926), but that I was determined on this occasion to adhere rigorously to the text. Later, however, I was approached by several students who asked if I would consider interpolating an account of the historical events I had felt constrained to omit. That I attempt to do here. It seems to me a story from which useful lessons can still be drawn. 1. Prior events. Schr¨odinger cultivated soil that had been prepared by others. Planck was led to write E = hν by his successful attempt (1900) to use the then-recently-established principles of statistical mechanics to account for the spectral distribution of thermalized electromagnetic radiation. It was soon appreciated that Planck’s energy/frequency relation was relevant to the understanding of optical phenomena that take place far from thermal equilibrium (photoelectric effect: Einstein 1905; atomic radiation: Bohr 1913). By 1916 it had become clear to Einstein that, while light is in some contexts well described as a Maxwellian wave, in other contexts it is more usefully thought of as a massless particle, with energy E = hν and momentum p = h/λ. -

Introduction to Waves

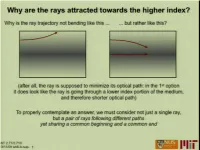

Paraxial focusing by a thin quadratic GRIN lens df n(r) r MIT 2.71/2.710 03/04/09 wk5-b- 2 Gradient Index (GRIN) optics: axial Stack Meld Grind &polish to a sphere • Result: Spherical refractive surface with axial index profile n(z) MIT 2.71/2.710 03/04/09 wk5-b- 3 Correction of spherical aberration by axial GRIN lenses MIT 2.71/2.710 03/04/09 wk5-b- 4 Generalized GRIN: what is the ray path through arbitrary n(r)? material with variable optical “density” P’ light ray P “optical path length” Let’s take a break from optics ... MIT 2.71/2.710 03/04/09 wk5-b- 5 Mechanical oscillator MIT 2.71/2.710 03/04/09 wk5-b- 6 MIT 2.71/2.710 03/04/09 wk5-b- 7 Hamiltonian Optics postulates s These are the “equations of motion,” i.e. they yield the ray trajectories. MIT 2.71/2.710 03/04/09 wk5-b- 8 The ray Hamiltonian s The choice yields Therefore, the equations of motion become Since the ray trajectory satisfies a set of Hamiltonian equations on the quantity H, it follows that H is conserved. The actual value of H=const.=const. isis arbitrary. MIT 2.71/2.710 03/04/09 wk5-b- 9 The ray Hamiltonian and the Descartes sphere =0 The ray momentum p p(s) is constrained to lie on n(q(s)) a sphere of radius n at any ray location q along the trajectory s Application: Snell’s law of refraction optical axis MIT 2.71/2.710 03/04/09 wk5-b- 10 The ray Hamiltonian and the Descartes sphere =0 The ray momentum p p(s) is constrained to lie on n(q(s)) a sphere of radius n at any ray location q along the trajectory s Application: propagation in a GRIN medium n(q) The Descartes sphere radius is proportional to n(q); as the rays propagate, the lateral momentum is preserved by gradually changing the ray orientation to match the Descartes spheres. -

Publishers Version

Existence and uniqueness of solutions to Liouville's equation and the associated flow for Hamiltonians of bounded variation Citation for published version (APA): Lith, van, B. S., Thije Boonkkamp, ten, J. H. M., IJzerman, W. L., & Tukker, T. W. (2014). Existence and uniqueness of solutions to Liouville's equation and the associated flow for Hamiltonians of bounded variation. (CASA-report; Vol. 1434). Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2014 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. -

Introduction to Optics

2.71/2.710 Optics 2.71/2.710 Optics • Instructors: Prof. George Barbastathis Prof. Colin J. R. Sheppard • Assistant Instructor: Dr. Se Baek Oh • Teaching Assistant: José (Pepe) A. Domínguez-Caballero • Admin. Assistant: Kate Anderson Adiana Abdullah • Units: 3-0-9, Prerequisites: 8.02, 18.03, 2.004 • 2.71: meets the Course 2 Restricted Elective requirement • 2.710: H-Level, meets the MS requirement in Design • “gateway” subject for Doctoral Qualifying exam in Optics • MIT lectures (EST): Mo 8-9am, We 7:30-9:30am • NUS lectures (SST): Mo 9-10pm, We 8:30-10:30pm MIT 2.71/2.710 02/06/08 wk1-b- 2 Image of optical coherent tomography removed due to copyright restrictions. Please see: http://www.lightlabimaging.com/image_gallery.php Images from Wikimedia Commons, NASA, and timbobee at Flickr. MIT 2.71/2.710 02/06/08 wk1-b- 3 Natural & artificial imaging systems Image by NIH National Eye Institute. Image by Thomas Bresson at Wikimedia Commons. Image by hyperborea at Flickr. MIT 2.71/2.710 Image by James Jones at Wikimedia Commons. 02/06/08 wk1-b- 4 Image removed due to copyright restrictions. Please see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LukeSkywalkerROTJV2Wallpaper.jpg MIT 2.71/2.710 02/06/08 wk1-b- 5 Class objectives • Cover the fundamental properties of light propagation and interaction with matter under the approximations of geometrical optics and scalar wave optics, emphasizing – physical intuition and underlying mathematical tools – systems approach to analysis and design of optical systems • Application of the physical concepts to topical -

D.D. Holm Y K.B. Wolf, Lie-Poisson Description of Hamiltonian Ray Optics, Physica D 51

Physica D 51 (1991) 189-199 North-Holland Lie-Poisson description of Hamiltonian ray optics Darryl D. Holm a and K. Bernardo Wolf b aCenter for Nonlinear Studies and Theoretical Division, Los Alamos National Laboratory, MS B284, Los Alamos, NM 87545, USA bInstituto de Investigaciones en Matemdticas Aplicadas yen Sistemas, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico-Cuernavaca, Apdo. Postal 20-726, 01000 Mexico D.F., Mexico We express classical Hamiltonian ray optics for light rays in axisymmetric fibers as a Lie-Poisson dynamical system defined in R 3, regarded as the dual of the Lie algebra sp(2, •). The ray-tracing dynamics is interpreted geometrically as motion in ~3 along the intersections of two-dimensional level surfaces of the conserved optical Hamiltonian and the skewness invariant (the analog of angular momentum, conserved because of the axisymmetry of the medium). In this geometrical picture, a Hamiltonian level surface is a vertically oriented cylinder whose cross section describes the radial profile of the refractive index, and a level surface of the skewness function is a hyperboloid of revolution around a horizontal axis. Points of tangency of these surfaces are equilibria, which are stable when the Gaussian curvature of the Hamiltonian level surface (constrained by the skewness function) is negative definite at the equilibrium point. Examples are discussed for various radial profiles of the refractive index. This discussion places optical ray tracing in fibers into the geometrical setting of Lie-Poisson Hamiltonian dynamics and provides an example of optical ray trapping within separatrices (homoclinic orbits). 1. Optical phase space qy The phase space of geometrical optics is four- //~'~q,z) dimensional. -

Lagrangian Mechanics - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 11

Lagrangian mechanics - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 11 Lagrangian mechanics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Lagrangian mechanics is a re-formulation of classical mechanics that combines Classical mechanics conservation of momentum with conservation of energy. It was introduced by the French mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange in 1788. Newton's Second Law In Lagrangian mechanics, the trajectory of a system of particles is derived by solving History of classical mechanics · the Lagrange equations in one of two forms, either the Lagrange equations of the Timeline of classical mechanics [1] first kind , which treat constraints explicitly as extra equations, often using Branches [2][3] Lagrange multipliers; or the Lagrange equations of the second kind , which Statics · Dynamics / Kinetics · Kinematics · [1] incorporate the constraints directly by judicious choice of generalized coordinates. Applied mechanics · Celestial mechanics · [4] The fundamental lemma of the calculus of variations shows that solving the Continuum mechanics · Lagrange equations is equivalent to finding the path for which the action functional is Statistical mechanics stationary, a quantity that is the integral of the Lagrangian over time. Formulations The use of generalized coordinates may considerably simplify a system's analysis. Newtonian mechanics (Vectorial For example, consider a small frictionless bead traveling in a groove. If one is tracking the bead as a particle, calculation of the motion of the bead using Newtonian mechanics) mechanics would require solving for the time-varying constraint force required to Analytical mechanics: keep the bead in the groove. For the same problem using Lagrangian mechanics, one Lagrangian mechanics looks at the path of the groove and chooses a set of independent generalized Hamiltonian mechanics coordinates that completely characterize the possible motion of the bead. -

Fermat's Principle and the Geometric Mechanics of Ray Optics Summer

Fermat's Principle and the Geometric Mechanics of Ray Optics Summer School Lectures, Fields Institute, Toronto, July 2012 Darryl D Holm Imperial College London [email protected] http://www.ma.ic.ac.uk/~dholm/ Texts for the course include: Geometric Mechanics I: Dynamics and Symmetry, & II: Rotating, Translating and Rolling, by DD Holm, World Scientific: Imperial College Press, Singapore, Second edition (2011). ISBN 978-1-84816-195-5 and ISBN 978-1-84816-155-9. Geometric Mechanics and Symmetry: From Finite to Infinite Dimensions, by DD Holm,T Schmah and C Stoica. Oxford University Press, (2009). ISBN 978-0-19-921290-3 Introduction to Mechanics and Symmetry, by J. E. Marsden and T. S. Ratiu Texts in Applied Mathematics, Vol. 75. New York: Springer-Verlag (1994). 1 Geometric Mechanics of Fermat Ray Optics DD Holm Fields Institute, Toronto, July 2012 2 Contents 1 Mathematical setting 5 2 Fermat's principle 8 2.1 Three-dimensional eikonal equation . 10 2.2 Three-dimensional Huygens wave fronts . 17 2.3 Eikonal equation for axial ray optics . 23 2.4 The eikonal equation for mirages . 29 2.5 Paraxial optics and classical mechanics . 32 3 Lecture 2: Hamiltonian formulation of axial ray optics 34 3.1 Geometry, phase space and the ray path . 36 3.2 Legendre transformation . 39 4 Hamiltonian form of optical transmission 42 4.1 Translation-invariant media . 49 4.2 Axisymmetric, translation-invariant materials . 50 4.3 Hamiltonian optics in polar coordinates . 53 4.4 Geometric phase for Fermat's principle . 56 4.5 Skewness . 58 4.6 Lagrange invariant: Poisson bracket relations . -

Intensity, Brightness And´Etendue of an Aperture Lamp 1 Problem

Intensity, Brightness and Etendue´ of an Aperture Lamp Kirk T. McDonald Joseph Henry Laboratories, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 (December 8, 2012; updated July 23, 2018) 1Problem An aperture lamp is a variant of a fluorescent bulb in which the phosphor1 is deposited on a reflecting substrate (which acts as a kind of optical insulator), and both of these exist over only a portion of the azimuth of the cylindrical glass housing, as sketched below. Phosphor molecules are excited by ultraviolet light emitted during the steady electrical discharge of the low-pressure gas inside the lamp, and subsequently de-excite via emission of visible light. Some of this light is absorbed and re-emitted by the phosphor. In this problem, assume that there are no losses in this absorption/re-emission. Compare the intensity, brightness and ´etendue of the light from an ordinary fluorescent lamp (with no reflector and phosphor over the full azimuth) with that of an aperture lamp, with small angular aperture Δφ, with the same power output in the visible light. You may assume that the phosphor surface emits radiation according to Lambert’s cosine law [2].2 Note that the principle of this problem applies equally well to a lamp consisting of an array of light-emitting diodes (which also absorb and re-emit light with little loss).3,4 Show that the effect of the phosphor/reflector (optical insulator) is to increase the inten- sity/brightness/temperature of the light inside the lamp (and the light emitted by it) for a 1 The phosphors are typically metal oxides with a PO4 radical, often with rare-earth elements. -

Nonimaging Optics

Introduction ho NONIMAGING OPTICS Julio Chaves Light Prescriptions Innovators Madrid, Spain (^oC) CRC Press V*^ / Taylor & Francis Group Boca Raton London New York CRC Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Croup, an Informa business Contents Foreword xv Preface xvii Acknowledgments xix Author xxi List of Symbols xxiii List of Abbreviations and Terms xxv Part I Nonimaging Optics 1 1 Fundamental Concepts 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Imaging and Nonimaging Optics 3 1.3 The Compound Parabolic Concentrator 8 1.4 Maximum Concentration 17 1.5 Examples 22 References 23 2 Design of Two-Dimensional Concentrators 25 2.1 Introduction 25 2.2 Concentrators for Sources at a Finite Distance 25 2.3 Concentrators for Tubular Receivers 27 2.4 Angle Transformers 29 2.5 The String Method 30 2.6 Optics with Dielectrics 35 2.7 Asymmetrical Optics 37 2.8 Examples 41 References 52 3 Etendue and the Winston-Welford Design Method 55 3.1 Introduction 55 3.2 Conservation of Etendue 57 3.3 Nonideal Optical Systems 63 3.4 Etendue as a Geometrical Quantity 65 3.5 Two-Dimensional Systems 68 3.6 Etendue as an Integral of the Optical Momentum 70 3.7 Etendue as a Volume in Phase Space 75 3.8 Etendue as a Difference in Optical Path Length 78 3.9 Flow Lines 83 3.10 The Winston-Welford Design Method 87 3.11 Caustics as Flow Lines 99 ix Contents 3.12 Maximum Concentration 102 3.13 Etendue and the Shape Factor 106 3.14 Examples 110 References 115 Vector Flux 117 4.1 Introduction 117 4.2 Definition of Vector Flux 121 4.3 Vector Flux as a Bisector of the Edge Rays 126 4.4 Vector -

Hamiltonian Mechanics - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 12

Hamiltonian mechanics - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 12 Hamiltonian mechanics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Hamiltonian mechanics is a reformulation of classical Classical mechanics mechanics that was introduced in 1833 by Irish mathematician William Rowan Hamilton. Newton's Second Law It arose from Lagrangian mechanics, a previous History of classical mechanics · reformulation of classical mechanics introduced by Joseph Timeline of classical mechanics Louis Lagrange in 1788, but can be formulated without Branches recourse to Lagrangian mechanics using symplectic spaces (see Mathematical formalism , below). The Hamiltonian Statics · Dynamics / Kinetics · Kinematics · method differs from the Lagrangian method in that instead Applied mechanics · Celestial mechanics · of expressing second-order differential constraints on an n- Continuum mechanics · dimensional coordinate space (where n is the number of Statistical mechanics degrees of freedom of the system), it expresses first-order constraints on a 2 n-dimensional phase space.[1] Formulations Newtonian mechanics (Vectorial As with Lagrangian mechanics, Hamilton's equations mechanics) provide a new and equivalent way of looking at classical Analytical mechanics: mechanics. Generally, these equations do not provide a more convenient way of solving a particular problem. Lagrangian mechanics Rather, they provide deeper insights into both the general Hamiltonian mechanics structure of classical mechanics and its connection to Fundamental concepts quantum mechanics as