ORGANIZING MR. SLOAN the Creation of the Modern Organization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rovement Here LIQUOR SEIZURE Present Frame of Mind

THE PRESS n A Home Town Paper F6r Home Town Folks. |THE ONLY NEWSPAPER pOTLISHEgll^ THE TO OF ENFIELD, CONN. ^11.--.. ;-T ..ll,........ •;*>•- FORTY-SIXTH YEAR—NO. 12. THOSfPSONVILLE, pONNECTlCl^V $OTRSDAY, JULY 16, 1925 PRICE $2.00 A YEAR—SINGLE COPY 5c .... ora mere disaster, but « folly developed' it was surely, when in the early stages of JEJviSi «"°^i last Thursday afternoon, w:»hitherto reliable press shuddered, staggered, N.. a- * .Y c°Uapsed into silence,, witn ^ne of its most important sections irreparably j® . m™lssi°n for the time being. _ For the mom^it our little newspaper world seemed hopeless- +V!T. O ^ V miss publication is the worst; j)iinster that could befall a newspaper. But only nd Superior Court Judge Brown Advises That the ] i "Jydread of such an ignonfcnous fate,—, whenmtvii withVT t VIA ac* snap, ourvut hope, courvvuiT( age and determination came back and we were at the telephone. Ourn,,,. predicament was hastily ex- Further Evidence of he Lack of Co-ordination Is Hartford and Springfield St. Railway Stop Do- P^'n®l to our ever accommodating neighbor, The ' lindsor Locks Journal. Could they help us ? Yes, a cheery reassuring yep, which was just whit ¥|e needed at the moment. "Come on bring your Disclosed During the Past Week When County », iitg Business On the Credit of the Court—The P""®. ^e will stay with you all night if neces$»j&" was the statement of genial and kindly Mr. ™aC.e of And we did. EpStefn, "who moves," moved faster than ever be- Officials Ignore the Local Police Department ^ : Bondholders To Foreclose—New Transporta- »T » l?S j **-, !. -

The Forbidden Zone Executives in China Are Frustrated Over New Internet Curbs That Restrict Their Ability to Stay in Touch with Foreign Clients and Their Headquarters

April 2015 The Forbidden Zone Executives in China are frustrated over new Internet curbs that restrict their ability to stay in touch with foreign clients and their headquarters ALSO INSIDE • Interview with Matt Tsien of GM • President’s Report APRIL 2015 INSIGThe Journal of the American Chamber of Commerceh in ShanghaiT AMCHAM SHANGHAI 11 By Peter Stratos PRESIDENT Taxing Errors Kenneth Jarrett 11 A tax expert sheds some light on common mistakes VP OF PROGRAMS & SErvicES American expats make on tax returns Scott Williams VP OF ADMINIStratioN & FINANCE helen Ren 18 DIREctorS In the Driver’s Seat By Bryan Virasami BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT & MARKETING 18 Matt Tsien, president of GM China, talks about the auto Patsy Li market, air quality and electric vehicles COMMITTEES Stefanie Myers EVENTS Jessica Wu 26 govERNMENT RElatioNS & CSR Cover Story: The Forbidden Zone Veomayoury "Titi" Baccam 26 By Kathryn Grant MEMBERSHIP & CVP The Internet in China is frustrating many business Linda X. Wang executives who interact regularly with overseas colleagues INSIGHT and clients EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Bryan Virasami 34 CONTENT MANagER Opinion: The Economic Fallout By Robert Atkinson Kathryn Grant 34 How China’s crackdown on the Internet will hurt the SENIOR ASSociatE EDitor economy Silvia Feng INTERNS Lois Delhom Anne Meredith Amanda Zhao INSIGht standards DESIGN 5 Movers & Shakers 9 President’s Report Alicia Beebe PRINTING MONTh IN PICTURES EXECUTIVE INTERVIEW Mickey Zhou Highlights from recent events Favorite Interview Question Snap Printing, Inc. 42 50 INSIGHT SPONSORSHIP INSIDE AMChAM (86-21) 6279-7119 ext. 5667 Story ideas, questions or 40 From the Chairman comments on Insight: Please contact 41 Board of Governors Meeting Bryan Virasami (86-21) 6279-7119 ext. -

NEWSPAPERS Monlclair Slate University

\ . .\ UNION COUNTY CLASSIFIED PAGE B16 - THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 6, 1997 Carjacking is down Still hitting the books According to the Prosecutor's A retired teacher authors his Office, incidences of carjacking fifth book, a history of 18th Automotive dropped again in 1996, Page B1. century Union. See Page B3, . AUTO FOR SALE AUTO WANTED AUTOMOTIVE 1994 JEEP GRAND CHEROKEE.-V-8. 4X4. ABLE PAYS TOP S$$ IN CASH Buick showcases the next automatic, 'attponanionlng, ABS. an power, premium stereo, alarm, many extras. 34.000 miles S18.5O0. 201-762-9462. ^ ' For All 4 Wheel Drives J l 1989 LINCOLN. SIGNATURE Series, black. CARS. TRUCKS and VANS - AUTO DEALERS Loaded. 4-door.leather. power seats, cruise. generation with the XP2000 59K Insta-dear windshield, car phono In- SMYTHE VOLVO cluded. Garage kept. $5900. 906-964-8850. FREE PICK UP 7 DAYS Buick's XP2000 showcases a new EXCLUSIVE 1989 LINCOLN CONTINENTAL, Signature series, bronze, tully loaded. 4 door.-leather 1-800-953-9328 generation of automotive technology. When the driver approaches the XP2000 after VOLVO DEALER seats, low mileage, car phone. $6,000 Best 326 Morris Avenue Summit : specifically selected to enhance the dark; the signal from the remote keyless fob otter. 201-379-6608. ' 908-688-2044 convenience, comfort and safety of (908) 273-4200 . 1988 LINCOLN TOWN Car,'garage kept, one Buick customers. While trje XP2000 turns on all of the white exterior lights, AUTHORIZED owner fabric top. fully loaded, cherry Wack 70,000 miles $7.000. 908-233-8299: 9-4. remains a dream-car. many of these FACTORY SERVICE including the headlamps and backup lumps, LONG TERM LEASING 1988 MERCURY COUGAR XR7, excellent "Your Best Source For Community Information" features will appear on real-world condition, white, blue leather interior, loaded, ^^ ~' 7 A buicks during the next lew Veins. -

STATE of MISSOURI ) ) Ss COUNTY of JACKSON ) AFFIDAVIT I, Jeffrey Weiland, a Special Agent with the Federal Bureau of Inves

STATE OF MISSOURI ) ) s s COUNTY OF JACKSON ) AFFIDAVIT I, Jeffrey Weiland, a Special Agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), being duly sworn, state the following is true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief: 1. I am a Special Agent with the FBI and have been employed in such a capacity since September 2007. I am currently assigned to the Criminal Enterprise Program, which investigates gangs, drugs, and organized crime matters. Prior to working for the FBI, I was employed as an attorney in Chicago, Illinois (2001-06) and as a law clerk to federal judges sitting on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals (2000-01) and the Northern District of Illinois (2006-07). The information in this complaint was obtained by me personally, from other FBI agents, and from police officers and police officers' official reports. 2. This affidavit is in support of a Complaint and Arrest Warrant for Michael Austin Leak, white male, date of birth August 11, 1990, for violations of Title 18, United States Code, Sections 371, 2113(a) and (d), and 2, Conspiracy to Commit Bank Robbery and Aiding and Abetting Armed Bank Robbery. A criminal history report shows that the Columbia, Missouri Police Department arrested Leak on one count of Stealing on January 30, 2008. 3. On Thursday, July 2, 2009, law enforcement personnel responded to a bank robbery at the Bank of Brookfield Purden located at 33332 Main, Winigan, Missouri. During the course of the investigation, it was learned that a lone white male entered the bank at approximately 9:02 a.m. -

(Bluffton, Ohio), 1948-06-03

THURSDAY, JUNE 3, 1948 THE BLUFFTON NEWS.l BLUFFTON, OHIO tery is mowed, it takes five men two and one-half days to trim by hand, Orange Twp. Sunday the grass around the monuments . School Convention and high school seniors back from NO FUSS ... NO MUSS Washington after seeing sights—it township school Public Salo must have been Northwestern Ohio convention will be held next Sunday senior week, anyway the Bluffton afternoon and evening at Liberty The undersigned will sell at public auction on the Vic Let the Washette do your family washing while you chapel. Green property located mile north or the second road June—bustin’ out all over—turned crowd reported meeting senior classes Officers are: Pres., Olney shop down town. Clothes washed and dried in an hour from Pandora and Kalida also tour I)aft; vice pres., 0. E. Zimmerman; to right on State Route 25 (Dixie Highway) from Bluffton, and a quarter. A up bright and smiling Tuesday’ morn Ohio on ing just as wonderful as any of those ing the capital—and speaking of the ■ec., Mrs. Mary Koontz Binkley. It’s Quick —I Convenient — Economical rare June days the poets describe Bluffton seniors, they say that four The program follows: . however, just to gbt down to of the girls are wearing diamond sol- Afternoon 2:30 P. M. Soft Water I— Parking Lot in Rear earth—a little shower wouldn’t be taires. amiss—fact is fields were pretty dry lev. Walter Purdy; Music, Riley Try it today—Hours 8 a. m.-to 5:30 p. -

Monthly Newsletter of the St Louis Chapter Buick Club of America Volume XXXVIII No

Monthly Newsletter of the St Louis Chapter Buick Club of America Volume XXXVIII No. 6 June 2019 Dedicated to the memory of Jeff Watkins Director’s Letter June, 2019 Greetings, Well folks, we start this month off with the passing of one of our founders and charter mem- bers, Jeff Watkins. Not only was Jeff a “Buick guy” but he was a true to the heart “car guy”. As a chartered member, he had a special love for the club and became a self-appointed histo- rian and an excellent resource for all things past. Jeff was also a collector of Buick and auto- motive literature. One of the things I will miss most about Jeff; every time he heard I ac- quired a new Buick, he would come to the next meeting with a sales brochure or some type of literature he had related to the car. And after each review, I would ask him if I could pur- chase it, and the answer was always the same, “NO”. Not too much is known about Jeff’s passing, but the family is planning a memorial in the near future and the club will be invited to share in his memory. Last year we honored Jeff with an Honorary Lifetime Membership for his forty years of ser- vice with the club. So for this month we dedicate our Gazette and member profile to Jeff Watkins. 1 On a happier note, “Thank You” to everyone who attended the car show and lunch at Laura Buick GMC in Collinsville, IL. I know many of you were traveling and had other commitments but we still had a good showing for the event. -

![(Bluffton, Ohio), 1948-05-20, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9279/bluffton-ohio-1948-05-20-p-4709279.webp)

(Bluffton, Ohio), 1948-05-20, [P ]

THE BLUFFTON NEWS, BLUFFTON, OHIO THURSDAY, MAY 20, 1948 PAGE TWO Couple Married In Birthday Dinner and Miss Collene Dangler of Ada. D. C. BIXEL, O.D. Couple Weds At The SCHOOLS and AIRPORT Mr. ana MW, Eail Rupright and Pandora Parsonage daughter Sandra Kay of Arlington GORDON BIXEL. O.D. Home Of Minister BOOST BLUFFTON SKY-HI Mr. and Mrs. John Marquart and 122 Baath Main St., Bluffton family entertained at a basket din were supper guests. EYEMIGHT $PBCIALISTS Wedding of Miss Doris Jean Bad-1 Sara Mae Oberly, daughter of Mr. ner Sunday in honor of the 19th Of flea Hours t ertscher, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. I Open Evening* A T100 u 0.00. and Mrs. Millard Oberly of Cherry birthday of their son Ivan Ray. The Closed 1 ay Aftam—n. Otto Badertscher, Bluffton, and Don-1 Fester To Address street was married to Howard Eldon aid Miller, son of Mr. and Mrs. Ed-1 table was centered with two large Beery, son of Mr. and Mrs. Howard ward Miller, Dalton, was solemnized I angel food cakes. College Varsity B Francis Bi Inger, D. D. S Beery of Col. Grove, Saturday morn Wednesday afternoon, May 12, at I Present were Mr. and Mrs. Charle^ ing at 10 o’clock in a ceremony at By Observing - 30th Air Mail Anniversary Wesley Fesler, head football coach Evan Bas ger, D. D. S. 3 o’clock at the home of the offi-l Main and daughter Charlene and the home of the officiating minister, Send Letters by AIRMAIL during Mrs. -

(Bluffton, Ohio), 1948-01-29

THURSDAY, JAN. 29. 1948 THE BLUFFTON NEWS, BLUFFTON. OHIO PAGE SEVEN / FOR PERFORMANCE— CONSERVATION AFFAIRS ALL DEAD STOCK REMOVED Happenings Affecting Woods, Waters and Wildlife We Pay 121 for Horses -- $23 for Cows By THE BLUFFTON COMMUNITY SPORTSMEN’S CLUB, INC. Build With Brick According to size and condition. —.r..1!.1., oesJSL-------------- - ogs according to size and condition. Sportsmen Meeting Planned Feeding birds at home is a pleasure ors have been elected to assist Mum and be sure to specify DUNBRICK, the superbrick. Truer The February meeting of the Bluff and interesting pastime. The mixture ma with the program: Vice president BUCKEY REDUCTION COMPANY, Findlay, Ohio is simply scattered on the ground in in form, higher in insulation value, lighter in weight than ton Community Sportsmen’s Club in charge, Ray Mumma; Moser Re will be held next Monday night, a sheltered area at times when snow serve, John Boehr; Rickly Reserve, Phone MAIN 475 Collect ordinary brick. Wide range of color variety; $25 per 8:00 p. m., Bluffton Town hall. covers all other food supply. Addi Howard Rickly; Rogers Reserve, Roy BRANCH OF FOSTORIA ANIMAL PRODUCTS. BfC thousand and up. Reorganization of the club into tion of cracklings, meat scraps, Rogers; College Reserve, Russell seven departments has been effected crumbs and other food scraps to the Lantz; Gratz Reserve, Andrew’ Gratz; by Gerald Clever, new club president. menu is also beneficial. Montgomery Reserve, Gilbert Mont For the coming year 56 officers and Wilbur Fish, heads the feeding pro gomery; Green Reserve, Vic Green; CONCRETE DRAIN TILE directors have been elected to carry gram for the Sportsmen Club, Boy Game Feeding, Wilbur Fish; Preda out a program embracing more than Scouts of Troop 56 jack up the feed tor Control, Russell Montgomery. -

Driving Force Will Enforcement to Arrest and Take Into Custody a Person Determined Efeature Members of the State to Have Been Engaged in Street Racing

Delivering Up-to-Date Information to America’s Car Clubs and Enthusiasts www.semasan.com MAY 2009 Taking the Lead California Lawmaker Assumes Leadership Post of State Auto Caucus alifornia Assemblyman Mike Duvall is the Duvall represents the 72nd Assembly District in new chairman of the SEMA-sponsored State California. He was first elected to the assembly in CAutomotive Enthusiast Leadership Cau- 2006 and re-elected in 2008. cus. Duvall succeeds New York Assemblyman Bill In a recent sit-down with the SAN, Duvall Reilich who served in that capacity since 2007. exclaimed, “Who knew that a guy who loves old cars Founded in 2005, the caucus is a bipartisan and Harleys could have fun in politics?” He added, group of state lawmakers whose common thread is “We need to keep this alive for future generations.” a love for automobiles. To date, almost 400 state Within a month of his arrival in Sacramento, legislators from all 50 states have joined the group. Duvall was appointed to the Vice-Chairmanship The caucus serves to raise the motor-vehicle hobby’s of the powerful Assembly Transportation Com- profile in state legislatures across the country and in mittee, which is tasked with overseeing the many the public’s eyes. Many of these lawmakers seek to roadway, rail, air and port operations of the Califor- preserve and expand the hobby by improving exist- nia Department of Transportation, Department of ing motor-vehicle statutes and regulations. Motor Vehicles and the California Highway Patrol. s Continued on page 2 CAUCUS CORNER LEGISLATIVE QUICK HITS California Street Racing: Existing law in California allows law ach month Driving Force will enforcement to arrest and take into custody a person determined E feature members of the State to have been engaged in street racing. -

The Antique Expression

Volume 57, Issue 6 June-July 2015 My 1918 Buick Center Door Sedan By Bill Thomas was desirable and went over and looked About a year and a half ago I answered an ad at the center door. He said it would on Craig’s List listing some old cars. It was actually run! That made it more only about fifteen miles from my place. So I interesting. It was an older restoration drove over to New Waverly. Well, when I but appeared to have been kept inside arrived, the place was out in the woods and most of its life. The roof has some not very developed. There were old parts and issues but that was expected. The rest pieces of cars everywhere. I thought it looked of the car was tight and could be more like a junk yard than restorable cars. refinished without too much work. Finally we found the owner and he took us to a couple of old barns and there were some So, I worked out a deal on all three cars that had potential. vehicles and gave him a check for the An AACA Award Winning Newsletter Winning Award An AACA Gulf CoastGulf Region, Houston, Texas full amount. He said, “I have all the Outside was an old T fuel truck that caught titles,” which again, I found unusual. The Antique Expression my attention. So, we marked that one. Once Normally the title on cars this old can inside, there were two old Buicks. One was a be an issue. 1918 roadster, the other, a closed car, also a (Continued on page 2.) 1918 which I never knew Buick made, a center door sedan! Well, I knew the roadster Inside this issue: Lots of Birthdays 3 Big Hats & Little Whispers 7 Picnic & Party Info 10 The Antique Expression (Continued from page 1) books and found out both of these 18 Buicks apparently are very rare. -

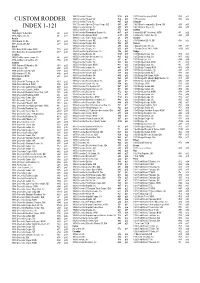

Custom Rodder Index #1-121

1940 Chevrolet Sedan #103 p26 1978 Corvettes (pair), NSW #85 p23 CUSTOM RODDER 1940 Chevrolet Sloper, Vic #26 p22 1979 Corvette #86 p22 1940 Chevrolet Truck, Vic #97 p28 Chrysler 1941 Chevrolet Special Deluxe Coupe, NZ #85 p31 1962 Chrysler Imperial Le Baron, SA #20 p33 INDEX 1-121 1946 Chevrolet pickup, Vic #55 p20 1962 Chrysler Royal, Vic #64 p35 Anglia 1947 Chevrolet ute, NSW #75 p30 Cortina 1948 Anglia Tudor, Qld #4 p29 1948 Chevrolet Fleetmaster Sedan, Vic #47 p38 Cortina 500 GT ‘Knockout’, NSW #7 p23 1958 Anglia van, Vic #8 p25 1948 Chevrolet pickup, NSW #107 p15 Cortina with Holden Six, Vic #55 p25 Austin 1950 Chevrolet Fisher body coupe, NSW #7 p28 Daimler 1939 Austin 10, SA #21 p29 1950 Chevrolet Coupe, NZ #25 p22 1939 Daimler DB-18, UK #67 p25 1951 Austin A40, NZ #15 p29 1952 Chevrolet Sedan, Qld #59 p27 Datsun Buick 1952 Chevrolet Sedan, Vic #85 p22 ? Datsun Coupe V8, Vic #75 p31 1930 Buick 8/90 Sedan, NSW #15 p32 1953 Chevrolet Coupe, Vic #50 p28 ? Datsun Chevy 240Z, NSW #100 p32 1940 Buick four door sedan, NSW #17 p19 1954 Chevrolet Sports Coupe, Vic #96 p30 Dodge Cadillac 1954 Chevrolet Bel Air, SA #101 p15 1917 Dodge bucket, SA #19 p30 1939 Cadillac opera coupe, Vic #4 p30 1955 Chevrolet two door sedan, Vic #20 p22 1925 Dodge pickup, SA #17 p22 1956 Cadillac Convertible, Vic #58 p19 1955 Chevrolet Coupe, Vic #31 p31 1925 Dodge ute, Vic #48 p38 Camaro 1955 Chevrolet Sedan, Vic #40 p32 1928 Dodge pickup, NSW #1 p32 1967 Camaro 500hp plus, SA #61 p22 1955 Chevrolet Coupe, NSW #41 p30 1928 Dodge pickup, Vic #3 p17 1967 Camaro, -

Safety Evaluation of Lane Change Collision Avoidance Systems Using

SAFETY EVALUATION OF LANE CHANGE in progress and is planned to be completed in mid COLLISION AVOIDANCE SYSTEMS USING 2005. THE NATIONAL ADVANCED DRIVING SIMULATOR INTRODUCTION Lane change collision avoidance systems (CAS) are designed to prevent crashes in lane change maneuvers by alerting the driver to hazards in the Alrik L. Svenson adjacent lanes of traffic. From previous studies, it National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has been determined that many crashes during a lane Valerie J. Gawron change occur when drivers are unaware of hazards around their vehicle. A CAS can detect surrounding General Dynamics vehicles that are in zones on the sides and behind the Timothy Brown vehicle and notify the driver through the use of a National Advanced Driving Simulator warning signal such as an auditory message or a United States of America visual symbol in the side or rear view mirrors. Lane change crashes account for approximately 5 percent Paper number 05-0249 of the total of all reported crashes in the General Estimates System (GES) data. To the extent that a CAS helps drivers avoid unsafe lane changes, it has ABSTRACT the potential to reduce crashes. This paper reports on the status of the evaluation of several lane change collision avoidance systems The Space and Electronics Group of TRW has (CAS) types using the National Advanced Driving developed a CAS consisting of two detection and Simulator (NADS). The goal of this evaluation is to warning subsystems [2]. The first subsystem, a examine driver behavior with a variety of lane proximity warning subsystem, detects vehicles in a change CAS to determine what leads to the safest defined proximity zone on the side of the vehicle driver behavior, and to investigate if the use of a lane including the region referred to as the blind spot.