Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

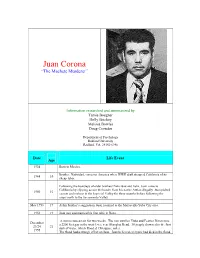

Juan Corona “The Machete Murderer”

Juan Corona “The Machete Murderer” Information researched and summarized by Tamie Boegner Holly Brickey Melissa Bowles Doug Crowder Department of Psychology Radford University Radford, VA 24142-6946 Date Life Event Age 1934 Born in Mexico. Brother, Natividad, comes to America when WWII draft strapped California of its 1944 10 cheap labor. Following the footsteps of older brothers Natividad and Felix, Juan came to California by slipping across the border from his native Autlan illegally. Juan picked 1950 16 carrots and melons in the Imperial Valley for three months before following the crops north to the Sacramento Valley. May 1953 19 At his brother’s suggestion, Juan returned to the Marysville-Yuba City area. 1953 19 Juan met and married his first wife in Reno. A storm caused rain for two weeks. The rain swollen Yuba and Feather Rivers tore December a 2200 feet gap in the west levee near Shanghai Bend. 38 people drowned in the first 23/24 21 rush of water, which flooded 150 square miles. 1955 The flood had a strange effect on Juan. Juan believed everyone had died in the flood and that he was living in a land of ghosts. Juan spent most of his free time during this period reading the Bible. After being returned by his brother to Mexico, Juan returns to the United States 1956 22 legally with a green card to work. Juan now gives up drinking. Natividad filed a petition in Yuba County Superior Court asking that his half brother 01-11-56 22 be committed to a mental hospital. -

Frequencies Between Serial Killer Typology And

FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS A dissertation presented to the faculty of ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY in CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY By Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori March 2016 FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS This dissertation, by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _______________________________ Ron Pilato, Psy.D. Chairperson _______________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Second Faculty _______________________________ Maxann Shwartz, Ph.D. External Expert ii © Copyright by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS LERYN ROSE-DOGGETT MESSORI Antioch University Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA This study examined the association between serial killer typologies and previously proposed etiological factors within serial killer case histories. Stratified sampling based on race and gender was used to identify thirty-six serial killers for this study. The percentage of serial killers within each race and gender category included in the study was taken from current serial killer demographic statistics between 1950 and 2010. Detailed data -

Books on Serial Killers

_____________________________________________________________ Researching the Multiple Murderer: A Comprehensive Bibliography of Books on Specific Serial, Mass, and Spree Killers Michael G. Aamodt & Christina Moyse Radford University True crime books are a useful source for researching serial killers. Unfortunately, many of these books do not include the name of the killer in the title, making it difficult to find them in a literature search. To make researching serial killers easier, we have created a comprehensive bibliography of true crime books on specific multiple murderers. This was done by identifying the names of nearly 1,800 serial killers and running searches of their names through such sources as WorldCat, Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and crimelibrary.com. This listing was originally published in 2004 in the Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology and was last updated in August, 2012. An asterisk next to a killer’s name indicates that a timeline written by Radford University students is available on the Internet at http://maamodt.asp.radford.edu/Psyc%20405/serial_killer_timelines.htm and an asterisk next to a book indicates that the book is available in the Radford University library. ______________________________________________________________________________________ Adams, John Bodkin Devlin, Patrick (1985). Easing the passing. London: Robert Hale. (ISBN 0-37030-627-9) Hallworth, Rodney & Williams, Mark (1983). Where there’s a will. Jersey, England: Capstans Press. (ISBN 0-946-79700-5) Hoskins, Percy (1984). Two men were acquitted: The trial and acquittal of Doctor John Bodkin Adams. London: Secker & Warburg (ISBN 0-436-20161-5) Albright, Charles* *Matthews, John (1997). The eyeball killer. NY: Pinnacle Books (ISBN 0-786-00242-5) Alcala, Rodney+ Sands, Stella (2011). -

Serial Killers

CHAPTER SEVEN SERIAL KILLERS hanks in part to a fascination with anything that is “serial,” whether it be T murder, rape, arson, or robbery, there has been a tendency to focus a good deal of attention on the timing of different types of multiple murder. Thus, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) distinguishes between spree killers who take the lives of several victims over a short period of time without a cooling-off period and serial killers who murder a number of people over weeks, months, or years, but in between their attacks live relatively normal lives.1 In 2008, for example, Nicholasdistribute T. Sheley, then 28, went on a killing spree across two states, beating as many as eight people to death over a period of several days in an effort to get money to buy crack. Sheley’s victims ranged from a child to a 93-year-old man.or At the time of these incidents, Sheley already had a long criminal history of robbery, drugs, and weapons convictions and had spent time in prison. Sheley is doing life in prison in Illinois for six of the murders and faces two additional homicide charges in Missouri. Unfortunately, the distinction between spree and serial killing can easily break down. For example, over the course of 2 weeks in 1997, Andrew Cunanan killed two victims in Minnesota, then drove to Illinois,post, where he killed another person, and then on to New Jersey, where he killed his fourth victim. While evading apprehension, and on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted List, Cunanan was labeled a spree killer. -

The BG News January 16, 1973

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 1-16-1973 The BG News January 16, 1973 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News January 16, 1973" (1973). BG News (Student Newspaper). 2795. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/2795 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. An Bowling Green, Ohio Independent Student Tuesday, January 16, 1973 Voice THe BG news Volumt 56 Number 54 Peace hopes soar as attacks subside KEY BISCAYNE. Fla lapi • Presi- press secretary Ronald L Ziegler and hours before the decision was an- dent Nixon halted all bombing, shelling was seen as a sign that the President nounced. and mining of North Vietnam yester- was satisfied with the outcome of Ziegler said shelling by Navy ships day, citing progress in Henry A Kissinger's six days of negotiations also was banned Mines already dotting Kissinger's Pans peace negotiations last week with Panoi's Le Due Tho. Paiphong harbor and other North Viet- The "unilateral gesture'' ordered by namese ports will remain in place, he Nixon sent peace hopes soaring and THE ORDER TO HALT all offensive said, and will be the subject of negotia- came amid a flood of reports that operations in North Vietnam effective tions. -

Herbariumscientist00mccarich.Pdf

of California Oral History Office University Regional California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, Women in Botany Project June McCaskill HERBARIUM SCIENTIST UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, DAVIS With an Introduction by John Tucker An Interview Conducted by Ann Lage in 1988 of California Copyright (c\ 1989 by The Regents of the University Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and June McCaskill dated February 28, 1989. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

3/16/15 1 Each Homicide Is Like Life Itself It Has a Beginning, a Middle

3/16/15 Each homicide is like life itself It has a beginning, a middle, John H. White, Ph.D. Forensic Psychologist and an end Stockton University ACFP – March 26,2015 Each crime scene tells a story Hotel clerk killed a pimp – left him A 5 year-old female chewed to where he fell – argument about death – left on killer’s property payment A person shot a male who was lying in under a bed bed in a motel – unknown motive A female bludgeoned to death, A female lying on the floor of her chains and cinderblocks apartment – killed by a serial killer – weighted her down – placed in staged lake 1 3/16/15 Female stabbed over fifteen times Prostitute stabbed in ally, left at scene in her bed – posed by ex Female strangled in hotel room – boyfriend serial killer 24 year-old female mutilated and 7-11 clerk shot execution style during a robbery left in a field – serial killer 7 year-old female abducted from a Woman stabbed 4 times, run over bus stop. Raped, strangled, placed in by car driven by ex husband a lake The location where the Police must determine specifics of the crime scene killer leaves the body If not, it may be left to Forensic May or may not be the Psychologists death scene 2 3/16/15 May be part of the modus M.O. --Comprised of those operandi (MO) actions necessary to commit May be part of a ritual the crime May be part of the signature Has three basic purposes: ◦ 1. -

Unty $Ffiilistorical Fficietv N.Wsbw.,[Etin

ffi"tter ffi"unty $ffiilistorical fficietv N.wsBW.,[etin Vol. XXXVII No. I Yuba City, California January, 1996 . ii:; (Phatograph credit: Ruby Romovich) TROWBRIDGE GENERAL STORE 2505 Nicor"'if"?oiul'3y.P-liff ' car ir' e5687 EONSAI STAWED GLASS ANNOUES PIAIVTS ffifter @"nry {$iluroricat fficiery N.*,9Wu[etin OFFICER,S OF THE S()CIETf' Bruce Harter, President Constance Cary, Secretary Steve Perry, Vice President Linda Leone, Treasurer f)ItrEcTc)R_s Audrey Breeding Jack Mclaughlin Constance Cary Stephen Perry Celia Ettt Evelyn Quigg Dewey Gruening Marian Regli Bruce Harter Randolph Schnabel Helen Heenan Sharyl Simmons Leonard Henson Edgar Stanton l-inda Leone Elaine Tarke' The News Burretin is pubrished quarterry by the society in Yuba city, carifornia. The annuar membership dues includes receiving the News Bulretin and the Museum,s lluse News. At the April L987 Annual Dinner Meeting it was voted to change the By-laws to cornbine the memberships of the Society and the Museum. The L996 dues are payable as of January L, 1996. Student (under 1_8)/Senior Citizen/Library g1O.OO Individual gl_5. OO Organizations/Clubs $ZS.oO Family g3o. oo Business/Sponsor glOO.OO Corporate/Benefactor 91, Ooo. oo PRINTED BY FIIVEB CIry PBINTING 583 2Nd STREET iN YUBA CMY (916) 755.02.17 PRESIDENT'S THOUGHTS Good day to you, Another calendar year is about to close its door upon our lives. A bright and shiny new gate is swinging wide open to what will be the best year of our lives here on Mother Earth. What we did accomplish in 1995 will be history, likewise what we did not do, but feel that we should have, will also be made history. -

Comprehensive School Safety Plan 2019-2020

0 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 School Safety Committee .............................................................................................................................. 5 Members ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Mission Statement .................................................................................................................................... 5 Vision Statement ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Review of 2018-2019 Goals ...................................................................................................................... 6 Goals for 2019-2020 .................................................................................................................................. 7 Assessment of School Safety......................................................................................................................... 8 Discipline Data .......................................................................................................................................... 8 School Survey ........................................................................................................................................... -

Murders by SCOTT HARBERS HOUSTON-As Many As 40 Teenage Boys May Have Died to Satisfy the Sadistic Sex Cravings of a 34-Year-Old "Nice Guy," Police Here Be- Lieve

HORROR IN HOUSTON Newspaper of America's Homophile Community So. Calif. 35C Issue 119 50C T~DVDCATE Elsewhere -\, ',. the r» y NEWSPAPER OF AMERICA'S HOMOPHILE COMMUNITY Copyright © 1973 ISSUE 119 Advocate Publications. Inc. AUGUST 29, 1973 Bays victim of gay' sadist • Toll may reach 40 inTexas murders by SCOTT HARBERS HOUSTON-As many as 40 teenage boys may have died to satisfy the sadistic sex cravings of a 34-year-old "nice guy," police here be- lieve. Nineteen bodies had been found as of Aug. 10. If the, number is anywhere near correct, it will be the nation's highest known toll of indisputably homosexual sex killings. Cali- ..• fornian Juan Corona is serving a life term for the murders of 2S men in 1971. but though those killings had INS IDE strong homosexual overtones. it was • • • never definitely established that . ~~:':i~a was homosexually moti-' AROUND TOWN Page38 r; Toll may reach 40 inTexas murders by SCOTT HARBERS HOUSTON-As many as 40 teenage boys may have died to satisfy the sadistic sex cravings of a 34-year-old "nice guy," police here be- lieve. Nineteen bodies had been found as of Aug. 10. If the, number is anywhere near correct, it will be the nation's highest known toll' of indisputably homosexual sex killings. Cali- -: fornian Juan Corona is serving a life term for 'the murders of 2S men in 1971, but though those killings had INS IDE ' strong homosexual overtones, it was ' '. • • never definitely established that ' Corona was homosexually moti-' AROUND TOWN Page 38 vated. The gruesome torture deaths at- AUNTIE LOU COOKS Page 29 tributed to Dean Corll of Pasadena, BODY BUDDY Page 31 a Houston suburb, over the past three years could prove a major set- BOOKS , . -

CALIFORNIA ODYSSEY the 1930S Migration to the Southern San Joaquin Valley

110 CALIFORNIA STATE COLLEGE, BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIA ODYSSEY The 1930s Migration to the Southern San Joaquin Valley Oral History Program Interview Between INTERVIEWEE: Frank Andy Manies PLACE OF BIRTH: Duncan, Stephens County, Oklahoma INTERVIEWER: Stacey Jagels DATES OF INTERVIEWS: February 18 and 20, 1981 PLACE OF INTERVIEWS: Tulare, Tulare County NUMBER OF TAPES: 4 TRANSCRIBER: Marsha A. Rink 110 PREFACE Mr. Frank Manies is a retired school teacher who now sells real estate in Tulare, California. Mr. Manies is well educated, articulate and extremely easy to talk to. He seemed to be aware of exactly what the Project was interested in learning through interviews and spoke on those subjects. Mr. Manies coped with some difficult times and still is very sensitive about them. He read the transcript carefully and edited a great deal of the interview himself. Stacey Jagels Interviewer llOsl CALIFORNIA STATE COLLEGE, BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIA ODYSSEY The 1930s Migration to the Southern San Joaquin Valley Oral History Program Interview Between INTERVIEWEE: Frank Andy Manies (Age: 66) INTERVIEWER: Stacey Jagels DATED: February 18, 1981 s .J.: This is an interview with Frank Andy Manies for the California State College, Bakersfield CALIFORNIA ODYSSEY Project, by Stacey Jagels at 957 Lyndale, Tulare, California on February 18, 1981 at 2:00 p.m. s .J.: First we'll start off with your childhood. When and where were you born? Manies: I was born in Duncan, Oklahoma which is in Stephens County, Oklahoma in 1915. We lived there for a couple years before we moved. There were two of us there. I am the third of four children. -

University of California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program Records, 1961-1996, Bulk 1969-1980

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt087031sh No online items Finding Aid to the University of California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program Records, 1961-1996, bulk 1969-1980 Finding Aid written by Finding Aid written by Janice Otani The Ethnic Studies Library 30 Stephens Hall #2360 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-2360 Phone: (510) 643-1234 Fax: (510) 643-8433 Email: [email protected] URL: http://eslibrary.berkeley.edu © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the University of CS ARC 2009/1 1 California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program Records, 19... Finding Aid to the University of California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program Records, 1961-1996, bulk 1969-1980 Collection Number: CS ARC 2009/1 The Ethnic Studies Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Finding Aid written by Janice Otani Date Completed: October 2009 © 2009 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: University of California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program records Date (inclusive): 1961-1996, Date (bulk): bulk 1969-1980 Collection Number: CS ARC 2009/1 Creators: University of California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program. Extent: Number of containers: 17 cartonsLinear feet: 21.25 Repository: University of California, Berkeley. Ethnic Studies Library 30 Stephens Hall #2360 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-2360 Phone: (510) 643-1234 Fax: (510) 643-8433 Email: [email protected] URL: http://eslibrary.berkeley.edu Abstract: The Chicano Studies Program records, 1961-1996 (bulk 1968-1980), provide materials relating to the formation of the program as a result of the Third World Strike student demands in 1969.