Frequencies Between Serial Killer Typology and Theorized Etiological Factors. Leryn R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release

Rick DiBasilio, Sheriff MEDIA RELEASE Contact: Lieutenant Greg Stark Release Date: August 23, 2021 Release Time: 9:05 AM Calaveras Sheriff’s Cold Case Team Exhumed Remains from Ng & Lake Serial Murder Cases with Hope in Updated DNA Technology The Calaveras County Sheriff’s Office has a small group of deputies who, in addition to their regular duties, review and investigate unsolved “Cold Cases”. Generally, the team focuses on unsolved homicides, missing persons, and unidentified remains. Advances in technology over the years have improved the ability to identify human remains including those previously determined to be unsuitable for DNA analysis. Recognizing these advances, the Calaveras County Sheriff’s Office contacted the California Department of Justice to discuss the possibility of identifying previously unidentified human remains associated with the Charles Ng and Leonard Lake serial killings. These crimes occurred in Wilseyville (Calaveras County) and in other locations in California during the 1980’s. Discussions, meetings, and planning have occurred over the past two years, and plans were made to remove the remains from their current location and submit them to the California Department of Justice for DNA analysis. At the conclusion of the criminal trial and conviction of serial killer Charles Ng in the 1990’s, the remains were placed into a crypt in a cemetery located in San Andreas, CA. As of the morning of August 17th, 2021, the remains were removed from the crypt following a few words and an invocation by a Sheriff’s Chaplain. The Calaveras County Sheriff’s Office Cold Case Team is working directly with Criminalists from the California Department of Justice and two expert Forensic Anthropologists to respectfully catalog and analyze the remains to determine their viability for DNA analysis. -

To Wrongful Convictions

1629 ACKER (DONE) 6/11/2013 4:04 PM THE FLIPSIDE INJUSTICE OF WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS: WHEN THE GUILTY GO FREE James R. Acker* I. INTRODUCTION As the rosters of identified wrongful convictions continue to swell,1 attention naturally focuses on the fractured lives of the innocent men and women who have endured the pains of unwarranted stigmatization and punishment. Their compound sufferings2 become all the more apparent as statistics that detail the incidence, causes, and consequences of miscarriages of justice * Distinguished Teaching Professor, School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany; J.D., Duke University; Ph.D., University at Albany. 1 The Innocence Project‘s list of wrongful convictions, confined to cases involving post- conviction DNA-based exonerations, is over three hundred. Facts on Post-Conviction DNA Exonerations, INNOCENCE PROJECT, http://www.innocenceproject.org/Content/Facts_on_PostConviction_DNA_Exonerations.php (last visited May 23, 2013) (identifying 307 post-conviction exonerations based on DNA since 1989). The National Registry of Exonerations identifies 891 exonerations in the United States since 1989 and includes descriptive information about 873 individuals wrongfully convicted through March 1, 2012. Exonerations in the United States, 1989–2012, Key Findings, NAT‘L REGISTRY EXONERATIONS 1 (May 20, 2012), http://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Documents/exonerations_us_1989_2012_summ ary.pdf; see also Exoneration Detail List, NAT‘L REGISTRY EXONERATIONS, http://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/detaillist.aspx (last visited May 18, 2013) (providing detailed exoneration information on 1123 individuals, including the year of exoneration). Not included are an additional 1170 individuals whose convictions were overturned in ―group exonerations‖ explained by police perjury or corruption. -

Death Row U.S.A

DEATH ROW U.S.A. Summer 2017 A quarterly report by the Criminal Justice Project of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Deborah Fins, Esq. Consultant to the Criminal Justice Project NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Death Row U.S.A. Summer 2017 (As of July 1, 2017) TOTAL NUMBER OF DEATH ROW INMATES KNOWN TO LDF: 2,817 Race of Defendant: White 1,196 (42.46%) Black 1,168 (41.46%) Latino/Latina 373 (13.24%) Native American 26 (0.92%) Asian 53 (1.88%) Unknown at this issue 1 (0.04%) Gender: Male 2,764 (98.12%) Female 53 (1.88%) JURISDICTIONS WITH CURRENT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 33 Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming, U.S. Government, U.S. Military. JURISDICTIONS WITHOUT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 20 Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico [see note below], New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin. [NOTE: New Mexico repealed the death penalty prospectively. The men already sentenced remain under sentence of death.] Death Row U.S.A. Page 1 In the United States Supreme Court Update to Spring 2017 Issue of Significant Criminal, Habeas, & Other Pending Cases for Cases to Be Decided in October Term 2016 or 2017 1. CASES RAISING CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS First Amendment Packingham v. North Carolina, No. 15-1194 (Use of websites by sex offender) (decision below 777 S.E.2d 738 (N.C. -

Mob Storms Into Tehran As Oil Halts

PAGE TWENTY-EIGHT - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD. Manchester, Conn.. Wed.. Dec. 27. I97B other information could you Now. I’m not sure what colic sometimes benefit cage near the gallbladder give me about treatment of kind of X ray you had for from a low-fat diet. Fat region may be confused with the colic? your gallbladder, but some stimulates the gallbladder to discomfort from gallbladder What’s up In auto theft? DEAR READER - It is stones show up on an X ray contract, resulting in colic. disease. unlikely that your pain is and other don’t, depending This is not true of either pure' When such patients have Think twice about parking your car on a Boston street. HEALTH caused by gallbladder colic. upon their chemical compo protein or carbohydrates. their gallbladder removed, According to a recent survey by a'leading Insurance V^y? Because you don’t sition. I am sending you The often they don’t get relief company, Beantown has the highest auto thelt rate In the 1 " Lawrence E.Lamb.M.D. have any gallstones. Most The ones that don’t have to Health Letter number 4-9, from their symptoms be nation. attacks of gallbladder colic be visualized by X ray after Gall Stones and Gall cause the pain wasn't Here are the auto theft rates per 100.000 people as well Senator*s Win Costly 1 East Catholic Boysj Girls 1 Body Count Now 17 1 Guyana Top Headliner are caused by sudden ob taking a gallbladder dye. Bladder Disease. It will give caused by the gallbladder to as the costs ol a comprehensive theft policy on a struction of the bile duct — T his^ usi^ally done by giv you more information on begin with. -

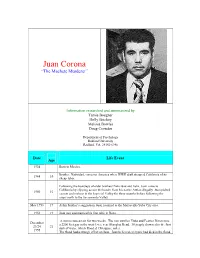

Juan Corona “The Machete Murderer”

Juan Corona “The Machete Murderer” Information researched and summarized by Tamie Boegner Holly Brickey Melissa Bowles Doug Crowder Department of Psychology Radford University Radford, VA 24142-6946 Date Life Event Age 1934 Born in Mexico. Brother, Natividad, comes to America when WWII draft strapped California of its 1944 10 cheap labor. Following the footsteps of older brothers Natividad and Felix, Juan came to California by slipping across the border from his native Autlan illegally. Juan picked 1950 16 carrots and melons in the Imperial Valley for three months before following the crops north to the Sacramento Valley. May 1953 19 At his brother’s suggestion, Juan returned to the Marysville-Yuba City area. 1953 19 Juan met and married his first wife in Reno. A storm caused rain for two weeks. The rain swollen Yuba and Feather Rivers tore December a 2200 feet gap in the west levee near Shanghai Bend. 38 people drowned in the first 23/24 21 rush of water, which flooded 150 square miles. 1955 The flood had a strange effect on Juan. Juan believed everyone had died in the flood and that he was living in a land of ghosts. Juan spent most of his free time during this period reading the Bible. After being returned by his brother to Mexico, Juan returns to the United States 1956 22 legally with a green card to work. Juan now gives up drinking. Natividad filed a petition in Yuba County Superior Court asking that his half brother 01-11-56 22 be committed to a mental hospital. -

America's Fascination with Multiple Murder

CHAPTER ONE AMERICA’S FASCINATION WITH MULTIPLE MURDER he break of dawn on November 16, 1957, heralded the start of deer hunting T season in rural Waushara County, Wisconsin. The men of Plainfield went off with their hunting rifles and knives but without any clue of what Edward Gein would do that day. Gein was known to the 647 residents of Plainfield as a quiet man who kept to himself in his aging, dilapidated farmhouse. But when the men of the vil- lage returned from hunting that evening, they learned the awful truth about their 51-year-old neighbor and the atrocities that he had ritualized within the walls of his farmhouse. The first in a series of discoveries that would disrupt the usually tranquil town occurred when Frank Worden arrived at his hardware store after hunting all day. Frank’s mother, Bernice Worden, who had been minding the store, was missing and so was Frank’s truck. But there was a pool of blood on the floor and a trail of blood leading toward the place where the truck had been garaged. The investigation of Bernice’s disappearance and possible homicide led police to the farm of Ed Gein. Because the farm had no electricity, the investigators con- ducted a slow and ominous search with flashlights, methodically scanning the barn for clues. The sheriff’s light suddenly exposed a hanging figure, apparently Mrs. Worden. As Captain Schoephoerster later described in court: Mrs. Worden had been completely dressed out like a deer with her head cut off at the shoulders. -

Frequencies Between Serial Killer Typology And

FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS A dissertation presented to the faculty of ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY in CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY By Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori March 2016 FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS This dissertation, by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _______________________________ Ron Pilato, Psy.D. Chairperson _______________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Second Faculty _______________________________ Maxann Shwartz, Ph.D. External Expert ii © Copyright by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS LERYN ROSE-DOGGETT MESSORI Antioch University Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA This study examined the association between serial killer typologies and previously proposed etiological factors within serial killer case histories. Stratified sampling based on race and gender was used to identify thirty-six serial killers for this study. The percentage of serial killers within each race and gender category included in the study was taken from current serial killer demographic statistics between 1950 and 2010. Detailed data -

Top 17 Cases Version 4/27/2020, with Addendum

2020 DNA Hit of the Year Top 17 Cases Version 4/27/2020, with Addendum * All addenda written by submitters. 1. Headless Outlaw’s Torso in Old Lava Tube Name of Submitter: Clark County Sheriff Bart May Location: Dubois, Idaho, U.S.A. Agency: Clark County Sheriff’s Office, Idaho Date of Crime: 1916 Date and Type of Hit: 2018-2019 (genetic genealogy to match with general family tree); 2018-2019 (familial match with living grandson to confirm family relationship) Executive Summary: 100-year-old unidentified human remains found in an old lava tube in 1979 leads to a cold case identification effort that lasts many years. However, his head was never located, baffling the FBI and other investigators for years. They could only establish that he was of European descent, with reddish-brown hair, and was about 40-years-old at the time of death. His arms, hand, and legs were found in 1991. Over the years, investigators enlisted the help of Idaho State University and its team of forensic genetic genealogists (anthropology students and staffers). This also included experts from the Smithsonian Institution and the FBI. Last year investigators further enlisted the help of the DNA Doe Project, hoping to use DNA and ancestral analysis to identify the man. Experts from Othram, a forensic DNA analysis company, analyzed samples taken from the remains, while a forensic genealogist from the DNA Doe Project worked with her colleagues to build a ‘genealogical tree’. The man’s DNA profile was then uploaded to various genetic genealogy DNA databases for relatives. This led to the man’s living 87-year-old grandson, whose sample was taken and tested to confirm a familial relationship. -

Prosecutor's Summary of the Evidence

WARNING: THE FOLLOWING SUMMARY CONTAINS GRAPHIC AND DISTURBING DESCRIPTIONS OF VIOLENT CRIMINAL ACTS AND MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR ALL READERS. IN PARTICULAR, FAMILY MEMBERS AND FRIENDS OF VICTIMS ARE CAUTIONED THAT THIS DOCUMENT DESCRIBES HIGHLY DISTURBING ELEMENTS OF THE CRIMES IN GRAPHIC DETAIL. 1 2 3 4 5 6 SUPERIOR COURT OF WASHINGTON FOR KING COUNTY 7 STATE OF WASHINGTON, 8 Plaintiff, No. 01-1-10270-9 SEA ) 9 vs. ) ) PROSECUTOR’S SUMMARY OF 10 GARY LEON RIDGWAY, ) THE EVIDENCE ) 11 Defendant, ) ) 12 ) ) 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Norm Maleng, Prosecuting Attorney W554 King County Courthouse 516 Third Avenue Seattle, Washington 98104 (206) 296-9000 FAX (206) 296-0955 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 I. INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................1 II. THIS DOCUMENT.......................................................................................................2 3 III. BACKGROUND...........................................................................................................2 A. THE GREEN RIVER KILLER: AN OVERVIEW ............................................2 4 B. RIDGWAY: GENERAL BACKGROUND........................................................4 C. THE INVESTIGATION INTO RIDGWAY.......................................................6 5 D. ARREST AND CHARGING..............................................................................8 E. THE PLEA AGREEMENT.................................................................................9 6 F. THE INTERVIEWS -

Canadian Broadcast Standards Council Ontario Regional Council

CANADIAN BROADCAST STANDARDS COUNCIL ONTARIO REGIONAL COUNCIL CTV re a News Report on Charles Ng’s Sentencing (CBSC Decision 98/99-1120) Decided March 22, 2000 P. Fockler (Vice-Chair), R. Cohen (ad hoc), M. Hogarth and M. Ziniak THE FACTS On June 30, 1999, CTV’s 11:00 p.m. National News reported the results of the sentencing hearing of Charles Ng which had concluded that day in a California court. Ng, the notorious serial killer who had escaped from California in 1985, was recaptured in Canada soon thereafter and extradited to the United States in 1991 to face trial, was found guilty in February 1999 of the murders of 1984 and 1985 murders of 11 individuals (six men, three women and two baby boys). Leonard Lake, his accomplice in those crimes, had committed suicide in 1985. After a lengthy hearing, Ng was sentenced to be executed by lethal injection. As a part of CTV’s 1 minute 47 second report of the outcome of that hearing, the network inserted a video clip of about seven seconds in length which showed either Ng or Lake beginning to cut the blouse of one of the female victims who was at that moment tied helplessly to a chair. The clip used was a short extract from one of the videotapes exhibited at the trial which had been shot by Ng and his cohort in the course of their sadistic crimes. The complainant wrote directly to CTV’s Vice President, News, and then to the CBSC two days later “to express [her] overwhelming anger at the complete decrepitude demonstrated by all involved in broadcasting” the brief clip showing the victim. -

“Tales of the Grim Sleeper” by Nick Broomfield

CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF RACISM, SOCIAL JUSTICE, & HEALTH Co-Sponsored with the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies and the Gary B. Nash Endowed Chair Film Screening & Discussion “Tales of the Grim Sleeper” By Nick Broomfield This film digs into the case of the notorious serial killer known as the Grim Sleeper, who terrorized black and other women in South Central LA over 25 years. Friday, May 18, 2018 12:00pm – 3:00pm ~ Room 33-105 CHS Fielding School of Public Health (Center for Health Sciences) Panelists: Margaret Prescod of KPFK Radio and Nana Gyamfi, human & civil rights attorney MARGARET PRESCOD In the mid-1980’s, in response to police reports of the serial murders of Black Women in South LA, Margaret founded the Black Coalition Fighting Back Serial Murders which resulted in the establishment of a reward by LA City and an LAPD task force to investigate the murders. Her work was reflected in the recent HBO film about the murders entitled “Tales of the Grim Sleeper.” The film was short listed for an Academy Award. She is the host and producer of “Sojourner Truth” a popular nationally syndicated drive-time public affairs program on Pacifica Radio’s KPFK in Los Angeles, WBAI in New York City and WPFW in Washington DC as well as several other stations. NANA GYAMFI Known as the ‘People's Attorney,' Nana Gyamfi is a human and civil rights advocate who seeks to address the social justice challenges of the community through legal advocacy, involvement in local causes and activism. In addition to being an attorney in private practice, she runs the Crenshaw Legal Clinic where she provides legal-ease workshops providing knowledge on civil rights, and is an adjunct professor at Cal State University Los Angeles in the Pan African Studies Department. -

Genealogical Trends in Solving Cold Cases: an Investigation Into the Merits and Concerns with New Cold-Case Lead Development

Midwest Social Sciences Journal Volume 22 Issue 1 Article 17 2019 Genealogical Trends in Solving Cold Cases: An Investigation into the Merits and Concerns with New Cold-Case Lead Development Katie Smolucha Indiana Institute of Technology Tyler Counsil Indiana Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/mssj Part of the Anthropology Commons, Business Commons, Criminology Commons, Economics Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Geography Commons, History Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Smolucha, Katie and Counsil, Tyler (2019) "Genealogical Trends in Solving Cold Cases: An Investigation into the Merits and Concerns with New Cold-Case Lead Development," Midwest Social Sciences Journal: Vol. 22 : Iss. 1 , Article 17. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/mssj/vol22/iss1/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Midwest Social Sciences Journal by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Smolucha and Counsil: Genealogical Trends in Solving Cold Cases: An Investigation into Genealogical Trends in Solving Cold Cases: An Investigation into the Merits and Concerns with New Cold-Case Lead Development* KATIE SMOLUCHA Indiana Institute of Technology TYLER COUNSIL Indiana Institute of Technology ABSTRACT In the criminal justice system, not all offenders are brought to justice; unfortunately, cold cases exist and provide long-term challenges to investigators. From historic breakthroughs in forensic DNA analysis to today’s new trends, advancements in technology continue to give investigators hope of resolving unsolved mysteries with no clear-cut suspect.