A Statute for Limburg?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

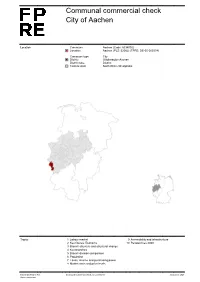

Communal Commercial Check City of Aachen

Eigentum von Fahrländer Partner AG, Zürich Communal commercial check City of Aachen Location Commune Aachen (Code: 5334002) Location Aachen (PLZ: 52062) (FPRE: DE-05-000334) Commune type City District Städteregion Aachen District type District Federal state North Rhine-Westphalia Topics 1 Labour market 9 Accessibility and infrastructure 2 Key figures: Economy 10 Perspectives 2030 3 Branch structure and structural change 4 Key branches 5 Branch division comparison 6 Population 7 Taxes, income and purchasing power 8 Market rents and price levels Fahrländer Partner AG Communal commercial check: City of Aachen 3rd quarter 2021 Raumentwicklung Eigentum von Fahrländer Partner AG, Zürich Summary Macro location text commerce City of Aachen Aachen (PLZ: 52062) lies in the City of Aachen in the District Städteregion Aachen in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Aachen has a population of 248'960 inhabitants (31.12.2019), living in 142'724 households. Thus, the average number of persons per household is 1.74. The yearly average net migration between 2014 and 2019 for Städteregion Aachen is 1'364 persons. In comparison to national numbers, average migration tendencies can be observed in Aachen within this time span. According to Fahrländer Partner (FPRE), in 2018 approximately 34.3% of the resident households on municipality level belong to the upper social class (Germany: 31.5%), 33.6% of the households belong to the middle class (Germany: 35.3%) and 32.0% to the lower social class (Germany: 33.2%). The yearly purchasing power per inhabitant in 2020 and on the communal level amounts to 22'591 EUR, at the federal state level North Rhine-Westphalia to 23'445 EUR and on national level to 23'766 EUR. -

The Dynamic Nordic Region Looking Back at the Past Year in the Nordic Council 2004And Nordic Council of Ministers

The Dynamic Nordic Region Looking back at the past year in the Nordic Council 2004and Nordic Council of Ministers 1 The Dynamic Nordic Region Looking back at the past year in the Nordic Council 2004and Nordic Council of Ministers The photographs in this annual report were taken during the Ses- Photos sion of the Nordic Council in Stockholm in early November 2004. Johan Gunséus cover, pp. 2, 5, 7-, 8, 11, 13, 14, 17, 18, The annual Session brings together parliamentarians, ministers, 21, 22, 23, 26, 31, 32, 37. journalists, civil servants and international guests for three days Magnus Fröderberg pp. 1, 4 (2nd from left), 16, 29, 35. of hectic and intense activity, meetings and debate. Personal Johannes Jansson p. 4 (1st from left). exchanges of opinions and ideas are an integral part of the Nordic democratic process. The Dynamic Nordic Region The Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers 2004 Further information: Please contact the Information Department: ANP 2005:705 www.norden.org/informationsavdelningen © The Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers, E-mail [email protected] Copenhagen 2005 Fax (+45) 3393 5818 ISBN 92-893-1109-6 Nordic co-operation Printer: Scanprint as, Århus 2005 Nordic co-operation, one of the oldest and most wide-ranging Production controller: Kjell Olsson regional partnerships in the world, involves Denmark, Finland, Design: Brandpunkt a/s Iceland, Norway, Sweden, the Faroe Islands, Greenland and the Copies: 1,500 Åland Islands. Co-operation reinforces the sense of Nordic commu- Printed on 130 g Arctic the Volume, environmentally friendly paper nity, while respecting national differences and similarities, makes as per the Nordic Swan labelling scheme. -

Die Euregiobahn

Stolberg-Mühlener Bahnhof – Stolberg-Altstadt 2021 > Fahrplan Stolberg Hbf – Eschweiler-St. Jöris – Alsdorf – Herzogenrath – Aachen – Stolberg Hbf Eschweiler-Talbahnhof – Langerwehe – Düren Bahnhof/Haltepunkt Montag – Freitag Mo – Do Fr/Sa Stolberg Hbf ab 5:11 6:12 7:12 8:12 18:12 19:12 20:12 21:12 22:12 23:12 23:12 usw. x Eschweiler-St. Jöris ab 5:18 6:19 7:19 8:19 18:19 19:19 20:19 21:19 22:19 23:19 23:19 alle Alsdorf-Poststraße ab 5:20 6:21 7:21 8:21 18:21 19:21 20:21 21:21 22:21 23:21 23:21 60 Alsdorf-Mariadorf ab 5:22 6:23 7:23 8:23 18:23 19:23 20:23 21:23 22:23 23:23 23:23 Minu- x Alsdorf-Kellersberg ab 5:24 6:25 7:25 8:25 18:25 19:25 20:25 21:25 22:25 23:25 23:25 ten Alsdorf-Annapark an 5:26 6:27 7:27 8:27 18:27 19:27 20:27 21:27 22:27 23:27 23:27 Alsdorf-Annapark ab 5:31 6:02 6:32 7:02 7:32 8:02 8:32 9:02 18:32 19:02 19:32 20:02 20:32 21:02 21:32 22:02 22:32 23:32 23:32 Alsdorf-Busch ab 5:33 6:04 6:34 7:04 7:34 8:04 8:34 9:04 18:34 19:04 19:34 20:04 20:34 21:04 21:34 22:04 22:34 23:34 23:34 Herzogenrath-A.-Schm.-Platz ab 5:35 6:06 6:36 7:06 7:36 8:06 8:36 9:06 18:36 19:06 19:36 20:06 20:36 21:06 21:36 22:06 22:36 23:36 23:36 Herzogenrath-Alt-Merkstein ab 5:38 6:09 6:39 7:09 7:39 8:09 8:39 9:09 18:39 19:09 19:39 20:09 20:39 21:09 21:39 22:09 22:39 23:39 23:39 Herzogenrath ab 5:44 6:14 6:44 7:14 7:44 8:14 8:44 9:14 18:44 19:14 19:44 20:14 20:45 21:14 21:44 22:14 22:44 23:43 23:43 Kohlscheid ab 5:49 6:19 6:49 7:19 7:49 8:19 8:49 9:19 18:49 19:19 19:49 20:19 20:50 21:19 21:49 22:19 22:49 23:49 23:49 Aachen West ab 5:55 6:25 6:55 -

Städteregionales Einzelhandelskonzept 113

StStSt ädteädterrrregionales EEEiEiii nzelhanzelhannnndelsdelsdelskkkkonzeponzeptttt STRIKT Aachen DurchführungDurchführung: ::: BBE RETAIL EXPERTS Unternehmensberatung GmbH & Co. KG Dipl.Dipl.- ---Geogr.Geogr. Rainer SchmidtSchmidt----IllguthIllguth Anna Heynen M.A. Auftraggeber: Zweckverband StädteRegion Aachen Aachen/Köln Oktober 2002008888 Mit freundlicher Unterstützung: Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite 1 Vorbemerkungen 1 1.1 Ausgangssituation und Zielsetzung 1 1.2 Methodische Vorgehensweise und Primärerhebungen 2 1.2.1 Angebotsanalyse 2 1.2.2 Nachfrageanalyse 3 2 Rahmenbedingungen der Einzelhandelsentwicklung 4 2.1 Siedlungsräumliche und demographische Strukturen 4 2.2 Einzelhandelsrelevantes Kaufkraftpotenzial in der StädteRegion 7 3 Einzelhandelsstrukturen in der StädteRegion 9 3.1 Überblick 9 3.1.1 Betriebe - Verkaufsflächen - Umsätze 9 3.1.2 Großflächiger Einzelhandel 12 3.1.3 Wohnungsnahe Versorgung 14 3.1.4 Einkaufsorientierung in der StädteRegion 17 3.1.5 Einzelhandelszentralitäten der Kommunen in der StädteRegion 19 3.2 Standortprofile der Kommunen in der StädteRegion 23 3.2.1 Stadt Aachen 23 3.2.1.1 Einzelhandelssituation im Überblick 23 3.2.1.2 Zentrale Versorgungsbereiche 28 3.2.1.3 Wohnungsnahe Grundversorgung in der Stadt Aachen 34 3.2.2 Stadt Alsdorf 35 3.2.2.1 Einzelhandelssituation im Überblick 35 3.2.2.2 Zentrale Versorgungsbereiche 40 3.2.2.3 Wohnungsnahe Grundversorgung in der Stadt Alsdorf 42 I 3.2.3 Stadt Baesweiler 43 3.2.3.1 Einzelhandelssituation im Überblick 43 3.2.3.2 Zentrale Versorgungsbereiche 48 3.2.3.3 Wohnungsnahe -

Voorstel Inrichting Buffergebied “De Baenjd” Datum; 25 November 2019

Voorstel Inrichting buffergebied “De Baenjd” Datum; 25 november 2019 Projectnaam: Kwistbeek fase 2 waterbuffer Projectnummer: 60-2019-OV-013 Projectgebied: Gemeente Peel en Maas Onderdeel: Helden Versie: Concept/praatstuk Document: Auteur: Ron Janssen Trekkers: Ron Janssen ism gemeente Peel en Maas 1. Inleiding Binnen de gemeente Peel en Maas wordt werk gemaakt om de regenwaterproblematiek op te lossen. Vanuit het veranderende klimaat en de hoeveelheid verharding is het noodzakelijk dat regenwater “gebufferd” kan worden, waarna het gedoseerd zijn weg kan vervolgen. Binnen de gemeente Peel en Maas is samen met Waterschap Limburg het gebied “De Baenjd” benoemd als buffergebied. De gemeente heeft een structuur opgezet met werkgroepen en voor dit onderdeel wil men graag een plan, dat vroegtijdig besproken is met de omgeving. Daarom heeft IKL, Ron Janssen, inzet gepleegd vanuit de kaders Waterschap Limburg en de gemeente Peel en Maas om samen met de streek een voorstel uit te werken. Onderstaand de opzet van het voorstel, dat op 27 november besproken wordt in de Werkgroep. 2. Uitgangspunten en randvoorwaarden Vanuit de opdracht heeft IKL uitgangspunten meegekregen die duidelijk aangeven dat de buffer voor waterretentie functioneel moet zijn en te allen tijde zijn functie kan volbrengen. Vandaar heeft Antea berekend wat de inhoud van de retentiebuffer dient te zijn. Gemeente heeft de beoogde locatie aangegeven. Vanuit deze uitgangspunten heeft de gemeente en werkgroep aangeven wat de aanvullende randvoorwaarden zijn: • Inrichting gebied dient een bijdrage te leveren aan de landschappelijke structuur/cultuurhistorische opbouw van het gebied • Ecologisch mogen bestaande waarden niet in het gedrang komen door wijziging watertoestand/instroom gebiedsvreemd water • De inrichting moet beheersbaar zijn, zodat de functionaliteit ten alle tijden gewaarborgd is. -

Exploring Vigilance Notification for Organs

NOTIFY - E xploring V igilanc E n otification for o rgans , t issu E s and c E lls NOTIFY Exploring VigilancE notification for organs, tissuEs and cElls A Global Consultation e 10,00 Organised by CNT with the co-sponsorship of WHO and the participation of the EU-funded SOHO V&S Project February 7-9, 2011 NOTIFY Exploring VigilancE notification for organs, tissuEs and cElls A Global Consultation Organised by CNT with the co-sponsorship of WHO and the participation of the EU-funded SOHO V&S Project February 7-9, 2011 Cover Bologna, piazza del Nettuno (photo © giulianax – Fotolia.com) © Testi Centro Nazionale Trapianti © 2011 EDITRICE COMPOSITORI Via Stalingrado 97/2 - 40128 Bologna Tel. 051/3540111 - Fax 051/327877 [email protected] www.editricecompositori.it ISBN 978-88-7794-758-1 Index Part A Bologna Consultation Report ............................................................................................................................................7 Part B Working Group Didactic Papers ......................................................................................................................................57 (i) The Transmission of Infections ..........................................................................................................................59 (ii) The Transmission of Malignancies ....................................................................................................................79 (iii) Adverse Outcomes Associated with Characteristics, Handling and Clinical Errors -

A Stronger Region the Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers 2006 06

Modern partnerships for a stronger Region The Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers 2006 06 06 Photos pp. 2, 25, 40: Pictures from “Reflections in the Northern Sky” – the international culture festival for indigenous peoples, held in Estonia. Photos pp. 2, 25 and 40: Kersti Sepper. Inset p. 25: Tiiu Kirsipuu. Front cover: The Gogmagogs music ensemble (part of the “Distur- Nordic cultural co-operation was reformed radically at the end of bances” Nordic music symposium). PR shot. Back cover (small 2006. Several institutions were discontinued and Nordic Culture pictures): Burst. Photo: G. Magni Agústsson; Vertebra. Photo: Petri Point was set up with a mandate to run multi-national and multi- Heikkilä; URGE. Photo: Ulrik Wivel; Polaroid. Photo: © Jo Strømgren genre programmes. The annual report features photographs Kompani. Photo (right): The Madman’s Garden, Martin Sirkovsky. illustrating various aspects of the multi-facetted cultural collabora- Photos pp. 1, 3, 28–29: Magnus Frölander (MF). Photos pp. 4, 9: tion that goes on under Nordic auspices or with official Nordic Johannes Jansson (JJ). Photos pp. 16–17: JJ; JJ; MF; JJ; MF; MF; MF; support. The worlds of dance, opera, poetry and the theatre are MF; MF; MF; MF; MF; JJ; JJ; MF. all portrayed along with a depiction of the Nordic Computer Games programme. The photographs are from the Faroe Islands in the west all the way to Latvia in the east and include a collage from the Annual Session of the Nordic Council in Copenhagen. Modern partnerships for a stronger Region The Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers 2006 ANP 2007:717 © The Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen 2007 ISBN 978-92-893-192-3 Print: Saloprint A/S, Copenhagen 2007 Design: Par No 1 A/S Copies: 800 Printed on environmentally friendly paper Printed in Denmark Nordic co-operation Nordic co-operation, one of the oldest and most wide-ranging regional partnerships in the world, involves Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, the Faroe Islands, Greenland and the Åland Islands. -

Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Countries

POWER, COMMUNICATION, AND POLITICS IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES POWER, COMMUNICATION, POWER, COMMUNICATION, AND POLITICS IN THE NORDIC COUNTRIES The Nordic countries are stable democracies with solid infrastructures for political dia- logue and negotiations. However, both the “Nordic model” and Nordic media systems are under pressure as the conditions for political communication change – not least due to weakened political parties and the widespread use of digital communication media. In this anthology, the similarities and differences in political communication across the Nordic countries are studied. Traditional corporatist mechanisms in the Nordic countries are increasingly challenged by professionals, such as lobbyists, a development that has consequences for the processes and forms of political communication. Populist polit- ical parties have increased their media presence and political influence, whereas the news media have lost readers, viewers, listeners, and advertisers. These developments influence societal power relations and restructure the ways in which political actors • Edited by: Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard Kristensen, & Lars Nord • Edited by: Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard communicate about political issues. This book is a key reference for all who are interested in current trends and develop- ments in the Nordic countries. The editors, Eli Skogerbø, Øyvind Ihlen, Nete Nørgaard Kristensen, and Lars Nord, have published extensively on political communication, and the authors are all scholars based in the Nordic countries with specialist knowledge in their fields. Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Nordicom is a centre for Nordic media research at the University of Gothenburg, Nordicomsupported is a bycentre the Nordic for CouncilNordic of mediaMinisters. research at the University of Gothenburg, supported by the Nordic Council of Ministers. -

The Political Alignment of the Centre Party in Wilhelmine Germany: a Study of the Party's Emergence in Nineteenth-Century Württemberg

The Political Alignment of the Centre Party in Wilhelmine Germany: A Study of the Party's Emergence in Nineteenth-Century Württemberg The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Blackbourn, David. 1975. The political alignment of the Centre Party in Wilhelmine Germany: A study of the party's emergence in nineteenth-century Württemberg. Historical Journal 18(4): 821-850. Published Version doi:10.1017/S0018246X00008906 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3629315 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Historical Journal, XVIII, 4 (I975), pp. 82I-850 821 Printed in Great Britain THE POLITICAL ALIGNMENT OF THE CENTRE PARTY IN WILHELMINE GERMANY: A STUDY OF THE PARTY'S EMERGENCE IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY WURTTEMBERG By DAVID BLACKBOURN Jesus College, Cambridge LESS than a month before Bismarck's dismissal as German chancellor, the Reichstag elections of February I890 destroyed the parliamentary majority of the Kartell parties - National Liberals and Conservatives - with whose support he had governed. The number of Reichstag seats held by these parties fell from 22I to I40, out of the total of397; they never again achieved more than I69. To the multitude of problems left by Bismarck to his successorswas there- fore added one of parliamentaryarithmetic: how was the chancellor to organize a Reichstag majority when the traditional governmental parties by themselves were no longer large enough, and the intransigently anti-governmental SPD was constantly increasing its representation? It was in this situation that the role of the Centre party in Wilhelmine politics became decisive, for between I890 and I9I4 the party possessed a quarter of the seats in the Reichstag, and thus held the balance of power between Left and Right. -

Challenging Times Need Focussed Policies and Programmes

Newsletter January 2011 European Alliance Group Challenging times need focussed CONTENT policies and programmes EA Rapporteur welcomes the crea- By EA Group President tion of the Intergroup on Health in the CoR As we begin the - Daiva Matonienė appointed CoR tions are now the past for regions will continue. Our rapporteur on the EU LIFE+ mid New Year reflec- group will strongly oppose any form of term review renationalisation of the Structural and coming to frui Cohesion funds. This is a clear message EA coordinator for EDUC Commis- tion on aCommon number that we will take to the Cohesion forum- sion welcomes 2011 as the Euro- Agriculture Policy of policy issues in- at the end of January. - pean year of Volunteering particular the future of the Focussed policies must also have tan- as well as the Struc gible benefits for regions and local au 2 CoR Plenary to adopt Brian Meaney’s tural Funds. We have argued on many thorities across the EU and then dis - opinion on biomass sustainability occasions for the need for a strong CAP cussing these in a European context, which will guarantee fully traceable, this is why I’m delighted that our col Francesco Musotto to take part in high quality food supply and security- leagues inSustainable the Scottish Tourism National Policy Party for the citizens of the EU as well as a have invited our group to Scotland to ARLEM Plenary Session in Agadir ‘fair’ income for farmers. We will con Asdiscuss we begin the European Year of Vol- tinue to reiterate our points to ensure unteeringon the 21st March 2011. -

Venlo Is in the Netherlands. We Are Called 'Blariacum College'. Http

Venlo is in the Netherlands. We are called 'Blariacum College'. http://www.blariacum.nl/ Venlo in southeastern Netherlands Venlo, Netherlands, location map Location of Venlo: Venlo is located in the southeast Netherlands in the Dutch province of Limburg near the border with Germany. The historic center of the town is located on the east side of the river Meuse. The population of Venlo is around 100,000 people. Getting to Venlo - Railway Station: Venlo offers intercity connections to Den Haag, Delft, Rotterdam and Eindhoven among other stations, with connections to Germany via Kaldenkirchen. Regional and city buses are located in front of the station, and there is a large parking lot as well. Venlo Carnival and Other Events: Venlo's carnival celebration is called Vastenaovend, and it's a grand celebration held six weeks before Easter. The main event is on Saturday and festivities continue until the next Tuesday. The Zomerparkfeest is a big arts festival held in the park near the train station. Need to know what to do in the area? Here's a long list: a day out in Limburg. If you like country living, or are looking for lodging during Floriade or carnival, you might have to look for places in the Limburg countryside. HomeAway lists a variety of Limburg Vacation Rentals. Closest Airports: Venlo is served by the airports of Düsseldorf (Germany), Maastricht, Eindhoven and Weeze (Germany). Tourist Office: VVV Venlo: The address of the tourist office is Nieuwstraat 40-42, 5911 Venlo. It's open Monday through Friday from 10 am to 5:30 pm and Saturday from 10am to 5pm. -

Summary of the Limburg Region Seminar, November 8-9, 2012

Local Scenarios of Demographic Change: Policies and Strategies for Sustainable Development, Skills and Employment Summary of the Limburg Region Seminar, November 8-9, 2012 Maastricht, December 7, 2012 Summary of the Limburg Region Seminar, November 8-9, 2012 Acknowledgements This summary note has been prepared by Andries de Grip (Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market, Maastricht University) and Inge Monteyne (Zeeland Regional Province). Aldert de Vries, Roxana Chandali (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations) and Silas Olsson (Health Access) and Karin Jacobs, Hans Mooren (Benelux Union) revised the note and provide useful comments for its final format. The note has been edited by Cristina Martinez-Fernandez (OECD LEED Programme), Tamara Weyman (OECD project consultant) and Melissa Telford (OECD consultant editor). Our gratitude to the workshop participants for their inputs and suggestions during the focus groups. 2 Summary of the Limburg Region Seminar, November 8-9, 2012 List of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Pre-workshop discussion and study visit ........................................................................................................... 4 Limburg Workshop ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Focus group 1. Opportunities within the cross-border labour