Rhodesian Ridgeback

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

The Care and Loving of Your New Rhodesian Ridgeback Puppy

Camelot Rhodesian Ridgebacks Clayton Heathcock & Cheri Hadley 5235 Alhambra Valley Road; Martinez, CA 94553; (925) 229-2944 http://steroid.cchem.berkeley.edu/Camelot The Care and Loving of Your New Rhodesian Ridgeback Puppy Table of Contents The first few nights (will be Hell--you might as well expect it) . 2 Crate training (providing your puppy with a life-long secure retreat) . 2 Feeding (the little critter needs lots of small meals at first) . 4 Inoculations (and other ways to minimize health risks during the critical first four months) . 6 Socializing (to other dogs and to people) . 7 Bite inhibition (nip it in the bud!) . 9 Obedience training (soon, or you’ll regret it!) . 9 Chewing (what’s his is his and what’s yours isn’t!) . 10 Exercise (Ridgebacks are natural couch potatoes, but they do need a place to unwind) . 11 Maintenance (dogears and toenails and teeth, oh my!) . 12 Dog shows (or, showing off your dog) . 13 Books and magazines about Ridgebacks . 17 Camelot Puppy Manual; revised November 5, 1998 page 2 The first few nights (will be Hell--you might as well expect it) For his entire short lifetime, your new puppy has spent virtually all of his time in a warm, cozy environment––first it was mom’s womb and then it was the ‘puppy pile’. If he got a little cold, he just had to burrow down to the bottom of the pile and he was warm. If he got a little lonesome, there were always plenty of siblings around for comfort. Things are different now that he is removed from his canine companions. -

Dog Breeds Pack 1 Professional Vector Graphics Page 1

DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 1 Affenpinscher Afghan Hound Aidi Airedale Terrier Akbash Akita Inu Alano Español Alaskan Klee Kai Alaskan Malamute Alpine Dachsbracke American American American American Akita American Bulldog Cocker Spaniel Eskimo Dog Foxhound American American Mastiff American Pit American American Hairless Terrier Bull Terrier Staffordshire Terrier Water Spaniel Anatolian Anglo-Français Appenzeller Shepherd Dog de Petite Vénerie Sennenhund Ariege Pointer Ariegeois COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 2 Armant Armenian Artois Hound Australian Australian Kelpie Gampr dog Cattle Dog Australian Australian Australian Stumpy Australian Terrier Austrian Black Shepherd Silky Terrier Tail Cattle Dog and Tan Hound Austrian Pinscher Azawakh Bakharwal Dog Barbet Basenji Basque Basset Artésien Basset Bleu Basset Fauve Basset Griffon Shepherd Dog Normand de Gascogne de Bretagne Vendeen, Petit Basset Griffon Bavarian Mountain Vendéen, Grand Basset Hound Hound Beagle Beagle-Harrier COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 2 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 3 Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bearded Collie Beauceron Bedlington Terrier (Tervuren) Dog (Groenendael) Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bergamasco Dog (Laekenois) Dog (Malinois) Shepherd Berger Blanc Suisse Berger Picard Bernese Mountain Black and Berner Laufhund Dog Bichon Frisé Billy Tan Coonhound Black and Tan Black Norwegian -

I First Became Involved with Rhodesian Ridgebacks in 1982

Ross Jones; Nominee for President I first became involved with Rhodesian Ridgebacks in 1982 when I met Cherie Starr of “Cimarron” and she and her Ridgebacks allowed myself and my Great Dane to become a part of their lives. We have bred 14 litters through the years and have attained a total of 35 titles on our puppies. These titles are in Conformation, Obedience and Lure Coursing. We owned, bred and handled the first Ridgeback Brace to go Best in Show and also the first Ridgeback Veteran to go Best In Show in a Veteran Exhibition. In the course of the following year I became a member of RRCUS as well as the local all breed club, Obedience Club, and Stewards Club. In other words I was “HOOKED”. I have been a Board Member of Rio Grande Kennel Club for the past 30 years and have held the position of Board Member, Vice- President and was President from 1994-1999 & 2014-present and am also the AKC Delegate. I was Show Chairman for 8 years and Cluster Chairman for the last 8 years. I am the equipment manager for the local Lure Coursing Club here in Albuquerque. Due to this exposure to the dog fancy I have become well versed in dealing with various personalities involved, dealing with the AKC and conducting the day-to-day business of an All Breed Club. I have served on various committees for Rhodesian Ridgeback Club of the US, and was appointed by the Board to the position of Recording Secretary in January 1999, and was re-elected in 2000. -

HOUND GROUP Photos Compliments of A.K.C

HOUND GROUP Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AFGHAN HOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AMERICAN ENGLISH COONHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AMERICAN FOXHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AZAWAKH HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BASENJI HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BASSET HOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BEAGLE HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BLACK AND TAN COONHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BLOODHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BLUETICK COONHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BORZOI HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H CIRNECO DELL’ETNA HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H DACHSHUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H ENGLISH FOXHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H GRAND BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H GREYHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H HARRIER HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H IBIZAN HOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H IRISH WOLFHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H NORWEGIAN ELKHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H OTTERHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. -

Border Collie

SCRAPS Breed Profile RHODESIAN RIDGEBACK Stats Country of Origin: Zimbabwe Group: Hounds Use today: Hunter and Guard Dog Life Span: 10 to 12 years Color: Coat colors include light wheaten to shades of red sometimes with a little white on the chest and toes. Coat: The coat is short and dense with a clearly defined symmetrical ridge of hairs growing in the opposite direction down the middle of the back. Grooming: The smooth, shorthaired coat is easy to groom. Brush with a firm bristle brush and shampoo only when necessary. This breed is an average shedder. Height: Males 25 - 27 inches; Females 24 - 26 inches Weight: Males 80 - 90 pounds; Females 65 - 75 pounds Profile In Brief: A large and muscular dog, the red sometimes with a little white on the chest Rhodesian Ridgeback was not only developed and toes. as hunter but also as a family protector. Due to their short coats Ridgebacks shed very little and Temperament: A fine hunter, the Rhodesian require only weekly brushing and occasional Ridgeback is ferocious in the hunt, but in the baths. The breed is also athletic, requiring home it is a calm, gentle, obedient, good dog. It regular exercise. Trustworthy with children, they is good natured, but some do not do well with are "people" dogs and like to be where you are, small children because they may play too possibly curled up on the couch if permitted. The roughly and knock them down. They are breed can be light wheaten to red wheaten and intelligent, skillful and straight-forward dogs that are sleek and glossy in appearance. -

Today's Breeder

® Today’s Breeder A Nestlé Purina Publication Dedicated to the Needs of Canine Enthusiasts Issue 74 BREEDER PROFILE Eternal Moon Rottweilers Odyssey German Shorthairs Retriever Trial Seminar Pug Dog Encephalitis Breeders Turned Show Judges old puppy. In April 2010, he went Best of Opposite Sex to Best of Variety (Smooth) at the Tri-County Collie Breeders Show. Vince will soon sire his first litter and continue his Specials career. I owe all his wins and success to Pro Plan and our regimen - Pro Club member Patti Simmons of Reed Creek Labs in Hartwell, Ga., shares this photo of her tal exercise program, which helps recent litter of 10 yellow Labrador Retriever puppies. keep him in great shape. I want to share this amazing Pro Club . All my puppies are raised on Jennifer Zappone photo of my recent litter sired by Pro Plan Chicken & Rice, and I feed Bluwave Collies Torrington, CT Temora Australian Terrier breeder Julie Seaton HRCH UH CH Kerrybrooks Vince, MH Pro Plan Chicken & Rice Shredded is shown with her Best of Opposite Sex winner (“Vince”) out of Ransom’s Alegría Blend to adult dogs. My dogs all I have been an exhibitor/breeder of at the 2010 National Specialty. @ ReedCreek, MH (“Alli”). What a have wonderful, shiny coats, and they Australian Terriers since 1995 and have wonderful litter. These 10 beautiful, eat well, which can be challenging always fed my dogs Purina Pro Plan At our 2010 National Specialty healthy puppies were started on Pro for the “picky” Collie. Performance and my puppies Pro Plan Show under judge Michelle Billings, Plan Selects puppy food, and I sent The first litter I bred produced a Puppy Chicken & Rice. -

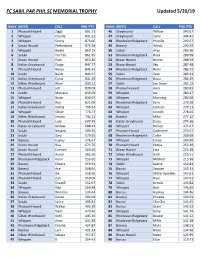

2019 Phil Trophy Statistics.Xlsx

FC SABIL PAR PHIL SC MEMORIAL TROPHY Updated 5/20/19 RANK BREED CALL PHIL PTS RANK BREED CALL PHIL PTS 1 Pharaoh Hound Ziggy 891.71 46 Greyhound Willow 340.67 2 Whippet Charlie 891.52 47 Greyhound Sonic 304.42 3 Whippet Sonny 873.06 48 Rhodesian Ridgeback Priscilla 292.67 4 Ibizan Hound Prefontaine 872.58 49 Basenji Windy 290.39 5 Whippet Bowie 863.75 50 Saluki Arya 289.36 6 Saluki Tsu'Tey 861.65 51 Rhodesian Ridgeback Roca 289.08 7 Ibizan Hound Puck 853.30 52 Ibizan Hound Breeze 288.59 8 Italian Greyhound Diego 847.77 53 Ibizan Hound Sky 287.48 9 Pharaoh Hound Rocco 845.42 54 Rhodesian Ridgeback Remi 286.72 10 Saluki Baida 844.97 55 Saluki Seze 285.31 11 Italian Greyhound Cyrus 841.49 56 Rhodesian Ridgeback Basia 284.49 12 Silken Windhound Khan 839.12 57 Saluki Jon Snow 281.13 13 Pharaoh Hound Jett 838.09 58 Pharaoh Hound Aura 280.83 14 Saluki Marzena 835.69 59 Whippet Isa 280.27 15 Whippet Ryder 830.67 60 Whippet Manning 280.00 16 Pharaoh Hound Roo 821.09 61 Rhodesian Ridgeback Kyra 279.28 17 Italian Greyhound Dottie 795.53 62 Whippet Jackson 279.13 18 Whippet Oliver 776.77 63 Whippet Lincoln 278.05 19 Silken Windhound Smoky 744.11 64 Basenji Miko 277.12 20 Pharaoh Hound Luke 697.49 65 Italian Greyhound Daisy 274.36 21 Italian Greyhound Willow 688.43 66 Whippet Nelson 271.67 22 Saluki Neyteri 593.95 67 Pharaoh Hound Cashmere 270.57 23 Saluki Zory 579.55 68 Rhodesian Ridgeback Callie 269.68 24 Basenji Cayley 576.67 69 Whippet Emoji 264.90 25 Ibizan Hound Risa 571.75 70 Pharaoh Hound Persia 252.40 26 Ibizan Hound Carmen 563.66 71 Ibizan -

Dianne P. Miller

Dianne P. Miller In the early 1980’s I acquired a Ridgeback puppy from my partner John who had two at the time and decided to breed. For many years I had owned and obedience trained Doberman Pinchers but I really got taken by the appearance and personality of the Rhodesian Ridgeback. For several years our Roughrider Kennel placed in the Top 5 in the Breed and won many All Hound Groups and Specialties. The late 1980’s brought us a lot of recognition with our puppies selling in the U.S.A. and Canada as well as Bermuda. In the 1990’s I developed my own breeding program under the prefix “SpruceRun Kennels” and had many successful dogs. Our kennel is mentioned in two published books of the breed one from England and one from Canada. After 17 years involvement of breeding and showing Ridgebacks I acquired an Australian Silky Terrier from Texas who became # 6 Toy in Canada 1991 and #3 Toy in Canada 1992. Six years later after numerous Champions and Toy Group placers I produced a Multiple Best in Show winner who became the All Time Top Canadian Bred Silky and # 3 Toy in Canada 1998 & 1999, his record still stands today. My Silkys are recognized in a published book of the breed from the United States. I have had the pleasure not only to live with Ridgebacks and Silkys but also some exquisite Wire-Haired and German Short Haired Pointers my husband owned so I have a great admiration for Sporting Breeds. Since the mid 1980’s I have bred over 40 Canadian Champions and 15 American Champions and applied for my Judging License in 1999. -

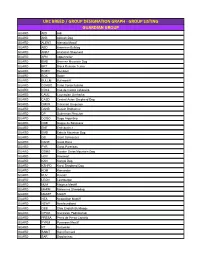

Ukc Breed / Group Designation Graph

UKC BREED / GROUP DESIGNATION GRAPH - GROUP LISTING GUARDIAN GROUP GUARD AIDI Aidi GUARD AKB Akbash Dog GUARD ALENT Alentejo Mastiff GUARD ABD American Bulldog GUARD ANAT Anatolian Shepherd GUARD APN Appenzeller GUARD BMD Bernese Mountain Dog GUARD BRT Black Russian Terrier GUARD BOER Boerboel GUARD BOX Boxer GUARD BULLM Bullmastiff GUARD CORSO Cane Corso Italiano GUARD CDCL Cao de Castro Laboreiro GUARD CAUC Caucasian Ovcharka GUARD CASD Central Asian Shepherd Dog GUARD CMUR Cimarron Uruguayo GUARD DANB Danish Broholmer GUARD DP Doberman Pinscher GUARD DOGO Dogo Argentino GUARD DDB Dogue de Bordeaux GUARD ENT Entlebucher GUARD EMD Estrela Mountain Dog GUARD GS Giant Schnauzer GUARD DANE Great Dane GUARD PYR Great Pyrenees GUARD GSMD Greater Swiss Mountain Dog GUARD HOV Hovawart GUARD KAN Kangal Dog GUARD KSHPD Karst Shepherd Dog GUARD KOM Komondor GUARD KUV Kuvasz GUARD LEON Leonberger GUARD MJM Majorca Mastiff GUARD MARM Maremma Sheepdog GUARD MASTF Mastiff GUARD NEA Neapolitan Mastiff GUARD NEWF Newfoundland GUARD OEB Olde English Bulldogge GUARD OPOD Owczarek Podhalanski GUARD PRESA Perro de Presa Canario GUARD PYRM Pyrenean Mastiff GUARD RT Rottweiler GUARD SAINT Saint Bernard GUARD SAR Sarplaninac GUARD SC Slovak Cuvac GUARD SMAST Spanish Mastiff GUARD SSCH Standard Schnauzer GUARD TM Tibetan Mastiff GUARD TJAK Tornjak GUARD TOSA Tosa Ken SCENTHOUND GROUP SCENT AD Alpine Dachsbracke SCENT B&T American Black & Tan Coonhound SCENT AF American Foxhound SCENT ALH American Leopard Hound SCENT AFVP Anglo-Francais de Petite Venerie SCENT -

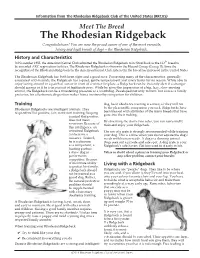

The Rhodesian Ridgeback

Information from The Rhodesian Ridgeback Club of the United States (RRCUS) Meet The Breed The Rhodesian Ridgeback Congratulations! You are now the proud owner of one of the most versatile, loving and loyal breeds of dogs—the Rhodesian Ridgeback. History and Characteristics In November 1955, the American Kennel Club admitted the Rhodesian Ridgeback to its Stud Book as the 112th breed to be accorded AKC registration facilities. The Rhodesian Ridgeback is shown in the Hound Group (Group II). Since the recognition of the Rhodesian Ridgeback by the American Kennel Club, interest in the breed has increased in the United States. The Rhodesian Ridgeback has both keen sight and a good nose. Possessing many of the characteristics generally associated with hounds, the Ridgeback has a quiet, gentle temperament and rarely barks for no reason. While able to enjoy lazing around in a patch of sun or in front of a winter fireplace, a Ridgeback can be instantly alert if a stranger should appear or if he is in pursuit of legitimate prey. While he gives the impression of a big, lazy, slow-moving animal, the Ridgeback can be a threatening presence as a watchdog. Developed not only to hunt, but also as a family protector, his affectionate dispostion makes him a trustworthy companion for children. Training dog, basic obedience training is a must, or they will not Rhodesian Ridgebacks are intelligent animals. They be the pleasurable companion you seek. Ridgebacks have respond well to positive, fair, consistent training, keeping been blessed with attributes of the many breeds that have in mind that positive gone into their making. -

Kurzform Rasse / Abbreviation Breed Stand/As Of: Sept

Kurzform Rasse / Abbreviation Breed Stand/as of: Sept. 2016 A AP Affenpinscher / Monkey Terrier AH Afghanischer Windhund / Afgan Hound AID Atlas Berghund / Atlas Mountain Dog (Aidi) AT Airedale Terrier AK Akita AM Alaskan Malamute DBR Alpenländische Dachsbracke / Alpine Basset Hound AA American Akita ACS American Cocker Spaniel / American Cocker Spaniel AFH Amerikanischer Fuchshund / American Foxhound AST American Staffordshire Terrier AWS Amerikanischer Wasserspaniel / American Water Spaniel AFPV Small French English Hound (Anglo-francais de petite venerie) APPS Appenzeller Sennenhund / Appenzell Mountain Dog ARIE Ariegeois / Arigie Hound ACD Australischer Treibhund / Australian Cattledog KELP Australian Kelpie ASH Australian Shepherd SILT Australian Silky Terrier STCD Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog AUST Australischer Terrier / Australian Terrier AZ Azawakh B BARB Franzosicher Wasserhund / French Water Dog (Barbet) BAR Barsoi / Russian Wolfhound (Borzoi) BAJI Basenji BAN Basst Artesien Normad / Norman Artesien Basset (Basset artesien normand) BBG Blauer Basset der Gascogne / Bue Cascony Basset (Basset bleu de Gascogne) BFB Tawny Brittany Basset (Basset fauve de Bretagne) BASH Basset Hound BGS Bayrischer Gebirgsschweisshund / Bavarian Mountain Hound BG Beagle BH Beagle Harrier BC Bearded Collie BET Bedlington Terrier BBS Weisser Schweizer Schäferhund / White Swiss Shepherd Dog (Berger Blanc Suisse) BBC Beauceron (Berger de Beauce) BBR Briard (Berger de Brie) BPIC Picardieschäferhund / Picardy Shepdog (Berger de Picardie (Berger Picard))