COMMODORE SIR JOHN DUTTON CLERK of PENICUIK, 10Th Baronet Sir John Clerk, Who Died on 25 October 2002, Was Not Himself a Scholar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Gazette, 25 March, 1930. 1895

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25 MARCH, 1930. 1895 panion of Our Distinguished Service Order, on Sir Jeremiah Colman, Baronet, Alfred Heath- whom we have conferred the Decoration of the cote Copeman, Herbert Thomas Crosby, John Military Cross, Albert Charles Gladstone, Francis Greenwood, Esquires, Lancelot Wilkin- Alexander Shaw (commonly called the Honour- son Dent, Esquire, Officer of Our Most Excel- able Alexander Shaw), Esquires, Sir John lent Order of the British Empire, Edwin Gordon Nairne, Baronet, Charles Joeelyn Hanson Freshfield, Esquire, Sir James Hambro, Esquire, Sir Josiah Charles Stamp, Fortescue Flannery, Baronet, Charles John Knight Grand Cross of Our Most Excellent Ritchie, Esquire, Officer of Our Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Sir Ernest Mus- Order of the British Empire; OUR right trusty grave Harvey, Knight Commander of Our and well-beloved Charles, Lord Ritchie of Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Dundee; OUR trusty and well-beloved Sir Sir Basil Phillott Blackett, Knight Commander Alfred James Reynolds, Knight, Percy Her- of Our Most Honourable Order of the Bath, bert Pound, George William Henderson, Gwyn Knight Commander of Our Most Exalted Order Vaughan Morgan, Esquires, Frank Henry of the Star of India, Sir Andrew Rae Duncan, Cook, Esquire, Companion of Our Most Knight, Edward Robert Peacock, James Lionel Eminent Order of the Indian Empire, Ridpath, Esquires, Sir Homewood Crawford, Frederick Henry Keeling Durlacher, Esquire, Knight, Commander of Our Royal Victorian Colonel Sir Charles Elton Longmore, Knight Order; Sir William Jameson 'Soulsby, Knight Commander of Our Most Honourable Order of Commander of Our Royal Victorian Order, the Bath, Colonel Charles St. -

Krantz [email protected] Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia + Delta Omicron = Sinfonicron G&S Works, with Date and Length of Original London Run • Thespis 1871 (63)

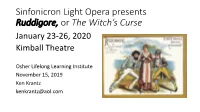

Sinfonicron Light Opera presents Ruddigore, or The Witch’s Curse January 23-26, 2020 Kimball Theatre Osher Lifelong Learning Institute November 15, 2019 Ken Krantz [email protected] Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia + Delta Omicron = Sinfonicron G&S Works, with date and length of original London run • Thespis 1871 (63) • Trial by Jury 1875 (131) • The Sorcerer 1877 (178) • HMS Pinafore 1878 (571) • The Pirates of Penzance 1879 (363) • Patience 1881 (578) • Iolanthe 1882 (398) G&S Works, Continued • Princess Ida 1884 (246) • The Mikado 1885 (672) • Ruddigore 1887 (288) • The Yeomen of the Guard 1888 (423) • The Gondoliers 1889 (554) • Utopia, Limited 1893 (245) • The Grand Duke 1896 (123) Elements of Gilbert’s stagecraft • Topsy-Turvydom (a/k/a Gilbertian logic) • Firm directorial control • The typical issue: Who will marry the soprano? • The typical competition: tenor vs. patter baritone • The Lozenge Plot • Literal lozenge: Used in The Sorcerer and never again • Virtual Lozenge: Used almost constantly Ruddigore: A “problem” opera • The horror show plot • The original spelling of the title: “Ruddygore” • Whatever opera followed The Mikado was likely to suffer by comparison Ruddigore Time: Early 19th Century Place: Cornwall, England Act 1: The village of Rederring Act 2: The picture gallery of Ruddigore Castle, one week later Ruddigore Dramatis Personae Mortals: •Sir Ruthven Murgatroyd, Baronet, disguised as Robin Oakapple (Patter Baritone) •Richard Dauntless, his foster brother, a sailor (Tenor) •Sir Despard Murgatroyd, Sir Ruthven’s younger brother -

Hutton S Geological Tours 1

Science & Education James Hutton's Geological Tours of Scotland: Romanticism, Literary Strategies, and the Scientific Quest --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: Full Title: James Hutton's Geological Tours of Scotland: Romanticism, Literary Strategies, and the Scientific Quest Article Type: Research Article Keywords: James Hutton; geology; literature; Romanticism; travel writing; Scotland; landscape. Corresponding Author: Tom Furniss University of Strathclyde Glasgow, UNITED KINGDOM Corresponding Author Secondary Information: Corresponding Author's Institution: University of Strathclyde Corresponding Author's Secondary Institution: First Author: Tom Furniss First Author Secondary Information: All Authors: Tom Furniss All Authors Secondary Information: Abstract: Rather than focussing on the relationship between science and literature, this article attempts to read scientific writing as literature. It explores a somewhat neglected element of the story of the emergence of geology in the late eighteenth century - James Hutton's unpublished accounts of the tours of Scotland that he undertook in the years 1785 to 1788 in search of empirical evidence for his theory of the earth. Attention to Hutton's use of literary techniques and conventions highlights the ways these texts dramatise the journey of scientific discovery and allow Hutton's readers to imagine that they were virtual participants in the geological quest, conducted by a savant whose self-fashioning made him a reliable guide through Scotland's geomorphology and the landscapes of -

SOSJ SJ Inner Workings 01 Post-Nominals (2) Revised Nov 17

Title: Deciphering Post-Nominal Letters Our Sovereign Order has a long and wonderful history and many traditions that reflect that history. These sometimes can be opaque to us today, and so from time to time it is helpful to review these “inner workings” to broaden the understanding among our members of how and why we do things. The letters after a person’s name tell us something about the person’s status and achievements within our Sovereign Order. To decipher this code, we need to be clear about three different elements of a person’s status within the order: 1) Type of membership 2) Rank and grade 3) Honours awarded. Types of Membership Our Constitution and Rules provide for three types of membership: 1) Dames and Knights – full members with voting rights, minimum age of 23 2) Demoiselles and Squires – full members without voting rights, minimum age of 18 3) Donats – employees or others serving the Sovereign Order being so honored. The third category is rarely used but provides a means by which a person who has faithfully served our Sovereign Order may be “admitted into the Order” while “not being admitted to full Membership.” Donats are not awarded post-nominal letters, and they needn’t be Christian so long as they have served faithfully and are deemed deserving of special recognition. Demoiselles and Squires are full members of our Sovereign Order. They are not awarded post-nominal letters but may hold offices of trust, though these usually will be at the Commandery level. They are eligible for promotion to Dame or Knight upon reaching the requisite age but, like all promotions, this must be earned by service and is adjudicated by the normal promotion assessment process. -

Lasswade & Kevock Conservation Area

Lasswade & Kevock Conservation Area Midlothian LASSWADE & KEVOCK CONSERVATION AREA Midlothian Strategic Services Fairfield House 8 Lothian Road Dalkeith EH22 3ZN Tel: 0131 271 3473 Fax: 0131 271 3537 www.midlothian.gov.uk 1 Lasswade & Kevock Conservation Area Midlothian Lasswade and Kevock CONTENTS Preface Page 3 Planning Context Page 4 Location and Population Page 5 Date of Designation Page 5 Archaeology and History Page 5 Character Analysis Lasswade Setting and Views Page 8 Urban Structure Page 8 Key Buildings Page 9 Architectural Character Page 10 Landscape Character Page 12 Issues Page 13 Enhancement Opportunities Page 13 Kevock Setting and Views Page 14 Urban Structure Page 14 Key Buildings Page 15 Architectural Character Page 15 Landscape Character Page 16 Issues Page 17 Enhancement Opportunities Page 17 Issues Applicable to the Whole Conservation Area Page 17 Character Analysis Map Page 19 Listed Buildings Page 20 Conservation Area Boundary Page 25 Conservation Area Boundary Map Page 26 Article 4 Direction Order Page 27 Building Conservation Principles Page 28 Glossary Page 30 References Page 33 2 Lasswade & Kevock Conservation Area Midlothian PREFACE attention to the character and appearance of the area when Conservation Areas exercising its powers under planning legislation. Conservation area status 1 It is widely accepted that the historic means that the character and environment is important and that a appearance of the conservation area high priority should be given to its will be afforded additional conservation and sensitive protection through development management. This includes plan policies and other planning buildings and townscapes of historic guidance that seeks to preserve and or architectural interest, open enhance the area whilst managing spaces, historic gardens and change. -

Titles – a Primer

Titles – A Primer The Society of Scottish Armigers, INC. Information Leaflet No. 21 Titles – A Primer The Peerage – There are five grades of the peerage: 1) Duke, 2) Marquess, 3) Earl, 4) Viscount and 5) Baron (England, GB, UK)/Lord of Parliament (Scotland). Over the centuries, certain customs and traditions have been established regarding styles and forms of address; they follow below: a. Duke & Duchess: Formal style: "The Most Noble the Duke of (title); although this is now very rare; the style is more usually, “His Grace the Duke of (Hamilton), and his address is, "Your Grace" or simply, "Duke” or “Duchess.” The eldest son uses one of his father's subsidiary titles as a courtesy. Younger sons use "Lord" followed by their first name (e.g., Lord David Scott); daughters are "Lady" followed by their first name (e.g., Lady Christina Hamilton); in conversation, they would be addressed as Lord David or Lady Christina. The same rules apply to eldest son's sons and daughters. The wife of a younger son uses”Lady” prior to her husbands name, (e.g. Lady David Scot) b. Marquess & Marchioness: Formal style: "The Most Honourable the Marquess/Marchioness (of) (title)" and address is "My Lord" or e.g., "Lord “Bute.” Other rules are the same as dukes. The eldest son, by courtesy, uses one of his father’s subsidiary titles. Wives of younger sons as for Dukes. c. Earl & Countess: Formal style: "The Right Honourable the Earl/Countess (of) (title)” and address style is the same as for a marquess. The eldest son uses one of his father's subsidiary titles as a courtesy. -

Sir Barry Close, 1St Baronet (3 December 1756 – 12 April 1813) Was an Army General in the East India Company and a Political Officer

Sir Barry Close, 1st Baronet (3 December 1756 – 12 April 1813) was an army general in the East India Company and a political officer. Barry Closei was born at Elm Park in Armagh, the third son of Maxwell Close and his wife Mary. The family had moved from Yorkshire to Ireland during the reign of Charles I. Barry joined the Madras army as a fifteen-year-old cadet in 1771 after his early schooling in Ireland. He was commissioned an ensign with the Madras infantry in 1773 and rose to become an adjutant of the 20th battalion in 1777. He saw action in the defence of Tellicherry against Hyder Ali and his General Sirdar Khan in 1780. Close's treatment of the sepoys and his leadership prevented his battalion from mutinying unlike several others. He gained a reputation as a linguist and chose to conduct all business with the sepoys in their own language. Close demonstrated his diplomatic talent when he served under James Stuart, commander-in-chief of the Madras army who was dismissed by Lord Macartney for not attacking the French. By handling this situation he rose in reputation and after becoming a captain on 18 December 1783, he was appointed to negotiate with Tipu Sultan. He served as deputy adjutant-general of the Madras army during the Siege of Seringapatam. Following this he was appointed adjutant-general and gazetted a lieutenant-colonel on 29 November 1797. Close founded the Madras military fund and promoted the formation of a permanent police committee to improve the law and order of Madras.[2] He was then posted to deal with the Mysore rulers drafting treaties with them. -

Supplement to Thelondon Gazette, 23 February, 1914

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 23 FEBRUARY, 1914. 1483 130 E. CHICHESTER of Raleigh. 4th Aug., 1641. Sir EDWARD GEORGE CHICHESTER lOtb Baronet. 131 E. KNATCHBULL of Mersham 4th Aug., 1641. Sir WYNDHAM KNATCHBULL, 12th Hatch. Baronet. 132 S. TURING of Foveran. 1641. Sir JAMES WALTER TURING, 9th Baronet. 133 S. CURZON of Kedleston. llth Aug., 1641. Sir ALFRED NATHANIEL HOLDEN CURZON, 8th Baronet ; 4th Baron Scarsdale. 134 E. LAWLEY of Spoonbill. 16th Aug., 1641. Sir EICHARD THOMPSON LAWLEY, llth Baronet; 4th Baron Wenlock. 135 E. TROLLOPE of Casewick. 5th Feb., 1642. Sir JOHN HENRY TROLLOPE, 8th Baronet; 2nd Baron Kesteven. 136 E. KEMP of Gissing. 14th March, 1642. Sir KENNETH HAGAR KEMP, 12th Baronet. 137 E. HAMPSON of Taplow. 3rd June, 1642. Sir GEORGE FRANCIS HAMPSON, 10th Baronet. 138 E. WILLIAMSON of East 3rd June, 1642. Sir HEDWORTH WILLIAMSON, 9th Markham. Baronet. 139 S. GORDON of Haddo. 13th Aug., 1642. Sir JOHN CAMPBELL GORDON, 9th Baronet; 7th Earl of Aberdeen. 140 E. THOROLD of Marston. 24th Aug., 1642. Sir JOHN HENRY THOROLD, 12th Baronet. 141 E. WROTTESLEY of Wrottes- 30th Aug., 1642. Sir VICTOR ALEXANDER WROTTESLEY, ley. 12th Baronet; 4th Baron Wrottes- ley. 142 E. THROCKMORTON of Cough- 1st Sept., 1642. Sir .NICHOLAS WILLIAM GEORGE ton. THROCKMORTON, 9th Baronet. 143 E. BLOUNT of Sodington. 6th Oct., 1642. Sir WALTER DE SODINGTON BLOUNT, 9th Baronet. 144 E. HAGGERSTON of Hagger- 15th Oct., 1642. Sir JOHN DE MARIE HAGGERSTON, ston. 9th Baronet. 145 E. LIDDELL of Ravensworth 2nd Nov., 1642. Sir ARTHUR THOMAS LIDDELL, 10th Castle. Baronet; 5th Baron Ravensworth. 146 E. -

Titles of Nobility, Hereditary Privilege, and the Unconstitutionality of Legacy Preferences in Public School Admissions

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Law Review Volume 84 Issue 6 2006 Titles of Nobility, Hereditary Privilege, and the Unconstitutionality of Legacy Preferences in Public School Admissions Carlton F. W. Larson University of California, Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Carlton F. W. Larson, Titles of Nobility, Hereditary Privilege, and the Unconstitutionality of Legacy Preferences in Public School Admissions, 84 WASH. U. L. REV. 1375 (2006). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol84/iss6/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TITLES OF NOBILITY, HEREDITARY PRIVILEGE, AND THE UNCONSTITUTIONALITY OF LEGACY PREFERENCES IN PUBLIC SCHOOL ADMISSIONS CARLTON F.W. LARSON∗ ABSTRACT This Article argues that legacy preferences in public university admissions violate the Constitution’s prohibition on titles of nobility. Examining considerable evidence from the late eighteenth century, the Article argues that the Nobility Clauses were not limited to the prohibition of certain distinctive titles, such as “duke” or “earl,” but had a substantive content that included a prohibition on all hereditary privileges with respect to state institutions. The Article places special emphasis on the dispute surrounding the formation of the Society of the Cincinnati, a hereditary organization formed by officers of the Continental Army. -

THE NEW ZEALAND · GAZETTE No. 27

568 THE NEW ZEALAND · GAZETTE No. 27 Orders, Decorations, and_ Medals British Empire Medal HJ!. Canada Medal!!. Queen's Police Medal, for Distinguished Service. THE following issued in a supplement to the London Gazette Queen's Fire Service Medal, for Distinguisheq. Service. of 14 January' 1958, is published for general information. Queen's Medal for Chiefs. · Dated at Wellington this 28th day of A~ril 1958. WAR MEDALS (in order of date of campaign for which awarded)§§. POLAR MEDALS (in .order of date). W. T. ANDERTON, Minister of Internal Affairs. Royal Victorian Medal (Gold, Silver and Bronze). Imperial Service Medal. CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD POLICE MEDALS FOR VALUABLE SERVICES Indian Police Medal for Meritorious Service. St. James's Palace, S. W. 1. Ceylon Police Medal for Merit. 14th January, 1958. Colonial Police Medal for Meritorious Service. THE following list shows the order in which Order1>, Decorations and Medals should be worn, and is to be substituted for the list dated 19 April 1955. It in no way affects the precedence conferred Badge of Honour. by the Statutes of certain Orders upon the Members thereof. JUBILEE, CORONATION AND DURBAR MEDALS- VICTORIA CROSSI!. Queen Victoria's Jubilee Medal, 1887 (Gold, Silver and Bronze). GEORGE CROSSI\. Queen Victoria's Police Jubilee Medal, 1887. Queen Victoria's Jubilee Medal, 1897 (Gold, Silver and Bronze).· BRITISH ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD, ETC. Queen Victoria's Police Jubilee Medal, 1897. Order of the Garter*II. Queen Victoria's Commemoration Medal, 1900 (Ireland). Order of the Thistle*II. King Edward VII's Coronation Medal, 1902. Order of St. -

War Medals, Orders and Decorations

War Medals, Orders and Decorations To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Book Room 34-35 New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Tuesday 18 July 2006 at 12.00 noon Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Friday 14 July 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 17 July 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 18 July 9.30 am to 11.30 am Or by previous appointment Catalogue no. 21 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Paul Wood or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 107 (front); Lot 119 (back); Lot 142 (inside front); Lots 172 and 171 (inside back) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. Estimates are published as a guide only and are subject to review. The actual hammer price of a lot may well be higher or lower than the range of figures given and there are no fixed “starting prices”. A Buyer’s Premium of 15% is applicable to all lots in this sale. -

155 Coping with a Title

Coping with a title: the indexer and the British aristocracy David Lee The names of peers occur frequently in books, and of course in their indexes. The English peerage system is not straightforward; it is so easy to make errors in the treatment of the names of peers and knights and their ladies, causing confusion to readers, that an article warning of pitfalls seems worthwhile.1 It is sometimes necessary to do research on peers and their titles, and this article gives the necessary clues. Whilst the article is in part general, the particular problems of indexers are covered, such as the form of name, and the order of entries. Introduction Beaumont. The 16th Duke's barony of Herries, however, First, a couple of warnings. This article is concerned was able to pass to a woman, and his eldest daughter, with the English peerage, and any statement cannot Lady Anne Fitzalan-Howard, duly became Baroness automatically be applied to practice in other countries. I Herries in her own right. At times a peerage may be in am no great expert on Scots and Irish peerage, so they abeyance, the final heir not being clear, and there are will crop up here rarely. Nor is this article concerned wonderful cases where claims to ancient peerages have with the special problems of indexing royalty. Further, been proved centuries later. It still happens, as in the case the article expresses one man's views and there can be of Jean Cherry Drummond, Baroness Strange, whose room for differences in interpretation and treatment, peerage came out of abeyance only in 1986, for much which I shall try to indicate as we go on.