The U.S. Military's Force Structure: a Primer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navy Columbia-Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program

Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 14, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R41129 Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program Summary The Navy’s Columbia (SSBN-826) class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) program is a program to design and build a class of 12 new SSBNs to replace the Navy’s current force of 14 aging Ohio-class SSBNs. Since 2013, the Navy has consistently identified the Columbia-class program as the Navy’s top priority program. The Navy procured the first Columbia-class boat in FY2021 and wants to procure the second boat in the class in FY2024. The Navy’s proposed FY2022 budget requests $3,003.0 (i.e., $3.0 billion) in procurement funding for the first Columbia-class boat and $1,644.0 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in advance procurement (AP) funding for the second boat, for a combined FY2022 procurement and AP funding request of $4,647.0 million (i.e., about $4.6 billion). The Navy’s FY2022 budget submission estimates the procurement cost of the first Columbia- class boat at $15,030.5 million (i.e., about $15.0 billion) in then-year dollars, including $6,557.6 million (i.e., about $6.60 billion) in costs for plans, meaning (essentially) the detail design/nonrecurring engineering (DD/NRE) costs for the Columbia class. (It is a long-standing Navy budgetary practice to incorporate the DD/NRE costs for a new class of ship into the total procurement cost of the first ship in the class.) Excluding costs for plans, the estimated hands-on construction cost of the first ship is $8,473.0 million (i.e., about $8.5 billion). -

A Case for a Tanker Capability for the U. S. Marine Corpsâ•Ž Heavy Lift

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2005 A Case for a Tanker Capability for the U. S. Marine Corps’ Heavy Lift Replacement Helicopter Anthony Cain Archer University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Archer, Anthony Cain, "A Case for a Tanker Capability for the U. S. Marine Corps’ Heavy Lift Replacement Helicopter. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1587 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Anthony Cain Archer entitled "A Case for a Tanker Capability for the U. S. Marine Corps’ Heavy Lift Replacement Helicopter." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Aviation Systems. Robert B. Richards, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Richard J. Ranaudo, U. Peter Solies Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Anthony Cain Archer entitled “A Case for a Tanker Capability for the U. -

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress (name redacted) Specialist in Naval Affairs December 13, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RS22478 Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress Summary Names for Navy ships traditionally have been chosen and announced by the Secretary of the Navy, under the direction of the President and in accordance with rules prescribed by Congress. Rules for giving certain types of names to certain types of Navy ships have evolved over time. There have been exceptions to the Navy’s ship-naming rules, particularly for the purpose of naming a ship for a person when the rule for that type of ship would have called for it to be named for something else. Some observers have perceived a breakdown in, or corruption of, the rules for naming Navy ships. On July 13, 2012, the Navy submitted to Congress a 73-page report on the Navy’s policies and practices for naming ships. For ship types now being procured for the Navy, or recently procured for the Navy, naming rules can be summarized as follows: The first Ohio replacement ballistic missile submarine (SBNX) has been named Columbia in honor of the District of Columbia, but the Navy has not stated what the naming rule for these ships will be. Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarines are being named for states. Aircraft carriers are generally named for past U.S. Presidents. Of the past 14, 10 were named for past U.S. Presidents, and 2 for Members of Congress. Destroyers are being named for deceased members of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, including Secretaries of the Navy. -

Beaufort Recognizes Navy Cross Recipient

Cobra Gold The 2018 Friday, February 16, 2018 Jet Vol. 53, No. 06 Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, S.C. “The noiseStream you hear is the sound of freedom.” 8 beaufort.marines.mil | facebook.com/MCASBeaufort | youtube.com/MCASBeaufort | mcasbetwitter.com/MCASBeaufortSC | Instagram/mcasbeaufort Check out our new website at Thejetstream- PROTECT WHAT YOU’VE EARNED beaufort.com Beaufort recognizes Navy Cross recipient Marines and Sailors salute the headstone of Petty Officer 1st Class William Pinckney while Taps is played at the Beaufort National Cemetery, Feb. 10. The new headstone gives proper recognition to Pinckney’s Navy Cross, the second highest award for valor. Pinckney was awarded the Navy Cross during World War II when he saved the life of an unconscious Sailor after a bomb exploded below the flight deck of their ship. At the time of the award, Pinckney was only the second African American in U.S. Navy history to receive the award. Ultimately, Pinckney was one of four African American Sailors to be awarded the Navy Cross. Story by itus professor at the University of Cpl. Benjamin McDonald South Carolina Beaufort. “After Photos by coordinating with the president Lance Cpl. Christian Moreno of the rotary club, we had a new A new headstone honoring headstone in three weeks. So here Petty Officer 1st Class William we all are today to remember this Pinckney was unveiled at the naval hero.” Beaufort National Cemetery, Feb. Pinckney was awarded the 10. Navy Cross while serving aboard The new headstone gives Petty the USS Enterprise aircraft car- Officer Pinckney appropriate rec- rier north of the Santa Cruz Is- ognition for his Navy Cross, the lands Oct. -

Development of Modern Control Laws for the AH-64D in Hover/Low Speed Flight

Development of Modern Control Laws for the AH-64D in Hover/Low Speed Flight Jeffrey W. Harding 1 Scott J. Moody Geoffrey J. Jeram 2 Aviation Engineering Directorate U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Research, Development, and Engineering Center Redstone Arsenal, Alabama M. Hossein Mansur 3 Mark B. Tischler Aeroflightdynamics Directorate U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Research, Development, and Engineering Center Moffet Field, California ABSTRACT Modern control laws are developed for the AH-64D Longbow Apache to provide improved handling qualities for hover and low speed flight in a degraded visual environment. The control laws use a model following approach to generate commands for the existing partial authority stability augmentation system (SAS) to provide both attitude command attitude hold and translational rate command response types based on the requirements in ADS-33E. Integrated analysis tools are used to support the design process including system identification of aircraft and actuator dynamics and optimization of design parameters based on military handling qualities and control system specifications. The purpose is to demonstrate the potential for improving the low speed handling qualities of existing Army helicopters with partial authority SAS actuators through flight control law modifications as an alternative to a full authority, fly-by-wire, control system upgrade. NOTATION INTRODUCTION ACAH attitude command attitude hold The AH-64 Apache was designed in the late 70’s and went DH direction hold into service as the US Army’s most advanced day, night DVE degraded visual environment and adverse weather attack helicopter in 1986. The flight HH height hold control system was designed to meet the relevant handling HQ handling qualities qualities requirements based on MIL-F-8501 (Ref. -

Assessment of Navy Heavy-Lift Aircraft Options

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation documented briefing series. RAND documented briefings are based on research briefed to a client, sponsor, or targeted au- dience and provide additional information on a specific topic. Although documented briefings have been peer reviewed, they are not expected to be comprehensive and may present preliminary findings. Assessment of Navy Heavy-Lift Aircraft Options John Gordon IV, Peter A. Wilson, Jon Grossman, Dan Deamon, Mark Edwards, Darryl Lenhardt, Dan Norton, William Sollfrey Prepared for the United States Navy Approved for public release; unlimited distribution The research described in this report was prepared for the United States Navy. -

January Cover.Indd

Accessories 1:35 Scale SALE V3000S Masks For ICM kit. EUXT198 $16.95 $11.99 SALE L3H163 Masks For ICM kit. EUXT200 $16.95 $11.99 SALE Kfz.2 Radio Car Masks For ICM kit. KV-1 and KV-2 - Vol. 5 - Tool Boxes Early German E-50 Flakpanzer Rheinmetall Geraet sWS with 20mm Flakvierling Detail Set EUXT201 $9.95 $7.99 AB35194 $17.99 $16.19 58 5.5cm Gun Barrels For Trumpter EU36195 $32.95 $29.66 AB35L100 $21.99 $19.79 SALE Merkava Mk.3D Masks For Meng kit. KV-1 and KV-2 - Vol. 4 - Tool Boxes Late Defender 110 Hardtop Detail Set HobbyBoss EUXT202 $14.95 $10.99 AB35195 $17.99 $16.19 Soviet 76.2mm M1936 (F22) Divisional Gun EU36200 $32.95 $29.66 SALE L 4500 Büssing NAG Window Mask KV-1 Vol. 6 - Lubricant Tanks Trumpeter KV-1 Barrel For Bronco kit. GMC Bofors 40mm Detail Set For HobbyBoss For ICM kit. AB35196 $14.99 $14.99 AB35L104 $9.99 EU36208 $29.95 $26.96 EUXT206 $10.95 $7.99 German Heavy Tank PzKpfw(r) KV-2 Vol-1 German Stu.Pz.IV Brumbar 15cm STuH 43 Gun Boxer MRAV Detail Set For HobbyBoss kit. Jagdpanzer 38(t) Hetzer Wheel mask For Basic Set For Trumpeter kit - TR00367. Barrel For Dragon kit. EU36215 $32.95 $29.66 AB35L110 $9.99 Academy kit. AB35212 $25.99 $23.39 Churchill Mk.VI Detail Set For AFV Club kit. EUXT208 $12.95 SALE German Super Heavy Tank E-100 Vol.1 Soviet 152.4mm ML-20S for SU-152 SP Gun EU36233 $26.95 $24.26 Simca 5 Staff Car Mask For Tamiya kit. -

OOB of the Russian Fleet (Kommersant, 2008)

The Entire Russian Fleet - Kommersant Moscow 21/03/08 09:18 $1 = 23.6781 RUR Moscow 28º F / -2º C €1 = 36.8739 RUR St.Petersburg 25º F / -4º C Search the Archives: >> Today is Mar. 21, 2008 11:14 AM (GMT +0300) Moscow Forum | Archive | Photo | Advertising | Subscribe | Search | PDA | RUS Politics Mar. 20, 2008 E-mail | Home The Entire Russian Fleet February 23rd is traditionally celebrated as the Soviet Army Day (now called the Homeland Defender’s Day), and few people remember that it is also the Day of Russia’s Navy. To compensate for this apparent injustice, Kommersant Vlast analytical weekly has compiled The Entire Russian Fleet directory. It is especially topical since even Russia’s Commander-in-Chief compared himself to a slave on the galleys a week ago. The directory lists all 238 battle ships and submarines of Russia’s Naval Fleet, with their board numbers, year of entering service, name and rank of their commanders. It also contains the data telling to which unit a ship or a submarine belongs. For first-class ships, there are schemes and tactic-technical characteristics. So detailed data on all Russian Navy vessels, from missile cruisers to base type trawlers, is for the first time compiled in one directory, making it unique in the range and amount of information it covers. The Entire Russian Fleet carries on the series of publications devoted to Russia’s armed forces. Vlast has already published similar directories about the Russian Army (#17-18 in 2002, #18 in 2003, and #7 in 2005) and Russia’s military bases (#19 in 2007). -

Iraq: Summary of U.S

Order Code RL31763 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Summary of U.S. Forces Updated March 14, 2005 Linwood B. Carter Information Research Specialist Knowledge Services Group Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Summary of U.S. Forces Summary This report provides a summary estimate of military forces that have reportedly been deployed to and subsequently withdrawn from the U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) Area of Responsibility (AOR), popularly called the Persian Gulf region, to support Operation Iraqi Freedom. For background information on the AOR, see [http://www.centcom.mil/aboutus/aor.htm]. Geographically, the USCENTCOM AOR stretches from the Horn of Africa to Central Asia. The information about military units that have been deployed and withdrawn is based on both official government public statements and estimates identified in selected news accounts. The statistics have been assembled from both Department of Defense (DOD) sources and open-source press reports. However, due to concerns about operational security, DOD is not routinely reporting the composition, size, or destination of units and military forces being deployed to the Persian Gulf. Consequently, not all has been officially confirmed. For further reading, see CRS Report RL31701, Iraq: U.S. Military Operations. This report will be updated as the situation continues to develop. Contents U.S. Forces.......................................................1 Military Units: Deployed/En Route/On Deployment Alert ..............1 -

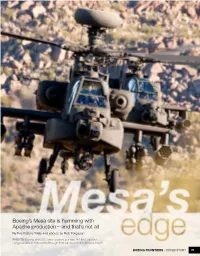

Boeing's Mesa Site Is Humming with Apache Production—And That's Not

Boeing’s Mesa site is humming with Apache production—and that’s not all By Eric Fetters-Walp and photos by Bob Ferguson PHOTO: Boeing and U.S. Army aviators put two AH-64D Apache Longbow attack helicopters through their paces over the Arizona desert. NOVEMBER 2011 BOEING FRONTIERS / COVER STORY 21 byMesa the numbers 1 ranking of Boeing Mesa’s business among all Arizona manufacturers 382 acres (155 hectares) comprising the Mesa site 576 number of Boeing suppliers or vendors in Arizona 1982 year Mesa site was established by Hughes Helicopters 4,500 approximate number of employees 8,300 hours volunteered by employees in 2010 he hot desert air above Mesa, making a growing array of components Ariz., frequently pulses with the for multiple Boeing aircraft. 1,900,000 T sound of Apache attack helicop- “We’ve gone from producing Block II ters as the intimidating machines are put Apaches two years ago to having three dollars given by Boeing Mesa and through their paces after emerging from and soon four production lines here today,” employees in charitable contributions the Boeing production line. first of the next-generation Apache Block III said Dave Koopersmith, Boeing Military during 2010 It’s a sound that’s become familiar over production models this fall. The U.S. Army Aircraft’s vice president of Attack Helicopter the nearly 30 years that the Mesa site has plans to order nearly 700 newly built or Programs and Mesa senior site executive, built Apaches for the U.S. Army and a remanufactured Block III helicopters, which referring to the two Apache production 2,000,000 growing number of international customers. -

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Updated July 29, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32492 American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Summary This report provides U.S. war casualty statistics. It includes data tables containing the number of casualties among American military personnel who served in principal wars and combat operations from 1775 to the present. It also includes data on those wounded in action and information such as race and ethnicity, gender, branch of service, and cause of death. The tables are compiled from various Department of Defense (DOD) sources. Wars covered include the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam Conflict, and the Persian Gulf War. Military operations covered include the Iranian Hostage Rescue Mission; Lebanon Peacekeeping; Urgent Fury in Grenada; Just Cause in Panama; Desert Shield and Desert Storm; Restore Hope in Somalia; Uphold Democracy in Haiti; Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF); Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF); Operation New Dawn (OND); Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR); and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). Starting with the Korean War and the more recent conflicts, this report includes additional detailed information on types of casualties and, when available, demographics. It also cites a number of resources for further information, including sources of historical statistics on active duty military deaths, published lists of military personnel killed in combat actions, data on demographic indicators among U.S. military personnel, related websites, and relevant CRS reports. Congressional Research Service American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

Neptune's Might: Amphibious Forces in Normandy

Neptune’s Might: Amphibious Forces in Normandy A Coast Guard LCVP landing craft crew prepares to take soldiers to Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944 Photo 26-G-2349. U.S. Coast Guard Photo, Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command By Michael Kern Program Assistant, National History Day 1 “The point was that we on the scene knew for sure that we could substitute machines for lives and that if we could plague and smother the enemy with an unbearable weight of machinery in the months to follow, hundreds of thousands of our young men whose expectancy of survival would otherwise have been small could someday walk again through their own front doors.” - Ernie Pyle, Brave Men 2 What is National History Day? National History Day is a non-profit organization which promotes history education for secondary and elementary education students. The program has grown into a national program since its humble beginnings in Cleveland, Ohio in 1974. Today over half a million students participate in National History Day each year, encouraged by thousands of dedicated teachers. Students select a historical topic related to a theme chosen each year. They conduct primary and secondary research on their chosen topic through libraries, archives, museums, historic sites, and interviews. Students analyze and interpret their sources before presenting their work in original papers, exhibits, documentaries, websites, or performances. Students enter their projects in contests held each spring at the local, state, and national level where they are evaluated by professional historians and educators. The program culminates in the Kenneth E. Behring National Contest, held on the campus of the University of Maryland at College Park each June.