On How We Use and Prioritize Communicative Cues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into the Mainstream Guide to the Moving Image Recordings from the Production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988

Descriptive Level Finding aid LANDER_N001 Collection title Into the Mainstream Guide to the moving image recordings from the production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988 Prepared 2015 by LW and IE, from audition sheets by JW Last updated November 19, 2015 ACCESS Availability of copies Digital viewing copies are available. Further information is available on the 'Ordering Collection Items' web page. Alternatively, contact the Access Unit by email to arrange an appointment to view the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on viewing The collection is open for viewing on the AIATSIS premises. AIATSIS holds viewing copies and production materials. Contact AFI Distribution for copies and usage. Contact Ned Lander and Yothu Yindi for usage of production materials. Ned Lander has donated production materials from this film to AIATSIS as a Cultural Gift under the Taxation Incentives for the Arts Scheme. Restrictions on use The collection may only be copied or published with permission from AIATSIS. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1988 Extent: 102 videocassettes (Betacam SP) (approximately 35 hrs.) : sd., col. (Moving Image 10 U-Matic tapes (Kodak EB950) (approximately 10 hrs.) : sd, col. components) 6 Betamax tapes (approximately 6 hrs.) : sd, col. 9 VHS tapes (approximately 9 hrs.) : sd, col. Production history Made as a one hour television documentary, 'Into the Mainstream' follows the Aboriginal band Yothu Yindi on its journey across America in 1988 with rock groups Midnight Oil and Graffiti Man (featuring John Trudell). Yothu Yindi is famed for drawing on the song-cycles of its Arnhem Land roots to create a mix of traditional Aboriginal music and rock and roll. -

Sustainable Aviation Fuels Road Map: Data Assumptions and Modelling

Sustainable Aviation Fuels Road Map: Data assumptions and modelling CSIRO Paul Graham, Luke Reedman, Luis Rodriguez, John Raison, Andrew Braid, Victoria Haritos, Thomas Brinsmead, Jenny Hayward, Joely Taylor and Deb O’Connell Centre of Policy Studies Phillip Adams May 2011 Enquiries should be addressed to: Paul Graham Energy Modelling Stream Leader CSIRO Energy Transformed Flagship PO Box 330 Newcastle NSW 2300 Ph: (02) 4960 6061 Fax: (02) 4960 6054 Email: [email protected] Copyright and Disclaimer © 2011 CSIRO To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Important Disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. CONTENTS Contents ..................................................................................................................... -

BEU Alm.Del - Bilag 28 Offentligt

Beskæftigelsesudvalget 2018-19 (2. samling) BEU Alm.del - Bilag 28 Offentligt Health effects of exposure to diesel exhaust in diesel-powered trains Maria Helena Guerra Andersen1,2*, Marie Frederiksen2, Anne Thoustrup Saber2, Regitze Sølling Wils1,2, Ana Sofia Fonseca2, Ismo K. Koponen2, Sandra Johannesson3, Martin Roursgaard1, Steffen Loft1, Peter Møller1, Ulla Vogel2,4 1Department of Public Health, Section of Environmental Health, University of Copenhagen, Øster Farimagsgade 5A, DK-1014 Copenhagen K, Denmark 2The National Research Centre for the Working Environment, Lersø Parkalle 105, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark. 3 Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Sahlgrenska Academy at University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. 4 DTU Health Tech., Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark *Corresponding author: [email protected]; [email protected] Maria Helena Guerra Andersen, [email protected]; [email protected] Marie Frederiksen, [email protected] Anne Thoustrup Saber, [email protected] Regitze Sølling Wils, [email protected] Ana Sofia Fonseca, [email protected] Ismo K. Koponen, [email protected] Sandra Johannesson, [email protected] Martin Roursgaard, [email protected] Steffen Loft, [email protected] Peter Møller, [email protected] Ulla Vogel, [email protected] Abstract Background: Short-term controlled exposure to diesel exhaust (DE) in chamber studies have shown mixed results on lung and systemic effects. There is a paucity of studies on well- characterized real-life DE exposure in humans. In the present study, 29 healthy volunteers were exposed to DE while sitting as passengers in diesel-powered trains. Exposure in electric trains was used as control scenario. -

2DAY-FM Chart, 1988-12-12

2DAY-FM TOP THIRTY SINGLES 2DAY-FM TOP THIRTY ALBUMS 2DAY-FM TOP THIRTY COMPACT DISCS No Title Artist Dist No Title Artist Dist No Title Artist Dist 1 Don't Worry Be Happy Bobby McFerrin EMI 1 * Barnestorming Jimmy Barnes Fest 1 Barnestorming Jimmy Barnes Fest 2 A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins WEA 2 "Cocktail" Sountrack WEA 2 Rattle and Hum U2 Fest 3 * If I Could 1927 WEA 3 Rattle and Hum U2 Fest 3 * "Cocktail" Soundtrack WEA 4 The Only Way Is Up Yazz & The Plastic CBS 4 Age Of Reason John Farnham BMG 4 Bryan Ferry Ultimate Collection Bryan Ferry/Roxy Music EMI Population 5 * Greatest Hits Fleetwood Mac WEA 5 * Greatest Hits Fleetwood Mac WEA 5 * Kokomo Beach Boys WEA 6 ...ISH 1927 WEA 6 Money For Nothing Dire Straits Poly 6 When A Man Loves A Woman Jimmy Barnes Fest 7 * Bryan Ferry Ultimate Collection Bryan Ferry/Roxy Music EMI 7 * The Best Of Chris Rea New Light Through Old WEA 7 I Want Your Love Transvision Vamp WEA 8 The Best Of Chris Rea New Light Through Old WEA Windows 8 Bring Me Some Water Melissa Etheridge Fest Windows 8 Age Of Reason John Farnham BMG 9 Wild, Wild West Escape Club WEA 9 Volume One Traveling Wilburys WEA 9 Kick INXS WEA 10 Nothing Can Divide Us Jason Donovan Fest 10 Kick INXS WEA 10 Union Toni Childs Fest 11 Teardrops Womack & Womack Fest 11 * Delicate Sound Of Thunder Pink Floyd CBS 11 * Melissa Etheridge Melissa Etheridge Fest 12 I Still Love You Oe Ne Sais Pas Pourquoi) Kylie Minogue Fest 12 Money For Nothing Dire Straits Poly 12 ...ISH 1927 WEA 13 Don't Need Love Johnny Diesel & The Fest 13 Union Toni -

Market Cost of Renewable Jet Fuel Adoption in the United States

Market Cost of Renewable Jet Fuel Adoption in the United States Niven Winchester, Dominic McConnachie, Chrisoph Wollersheim and Ian Waitz Report No. 238 January 2013 The MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change is an organization for research, independent policy analysis, and public education in global environmental change. It seeks to provide leadership in understanding scientific, economic, and ecological aspects of this difficult issue, and combining them into policy assessments that serve the needs of ongoing national and international discussions. To this end, the Program brings together an interdisciplinary group from two established research centers at MIT: the Center for Global Change Science (CGCS) and the Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research (CEEPR). These two centers bridge many key areas of the needed intellectual work, and additional essential areas are covered by other MIT departments, by collaboration with the Ecosystems Center of the Marine Biology Laboratory (MBL) at Woods Hole, and by short- and long-term visitors to the Program. The Program involves sponsorship and active participation by industry, government, and non-profit organizations. To inform processes of policy development and implementation, climate change research needs to focus on improving the prediction of those variables that are most relevant to economic, social, and environmental effects. In turn, the greenhouse gas and atmospheric aerosol assumptions underlying climate analysis need to be related to the economic, technological, and political forces that drive emissions, and to the results of international agreements and mitigation. Further, assessments of possible societal and ecosystem impacts, and analysis of mitigation strategies, need to be based on realistic evaluation of the uncertainties of climate science. -

A Collection of Stories from the Ground up by Dustin Clark A

A Collection of Stories from the Ground Up by Dustin Clark A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of Degree of Master of Fine Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL December 2009 Abstract Author: Dustin Clark Title: A Collection of Stories from the Ground Up Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Papatya Bucak, M.F.A. Degree: Master of Fine Arts Year: 2009 The stories proposed within this thesis examine the daily lives of working class men, women, and children and the subtle dynamics of the relationships between them. The stories engage a variety of narrative perspectives, sometimes employing serious overtones and sometimes shifting toward humor. Stylistically, the stories construct a single unified voice that sifts through common themes including alcoholism, self-pity, the loss of culture, grief, distrust, absolution, and hero worship. iii A Collection of Stories from the Ground Up The Great Regurgitator…………………………………………………………….…..…1 A Biography of Abraham Lincoln from Memory following Halloween Night 1996…...10 The Nickel…………………………………………………………………………..…...17 The Princess is in Danger…………………………………………………………..…....23 Connecting Rods…………………………………………………………………..….…30 The Junkyard……………………………………………………………………..….…..33 The Sledge……………………………………………………………………..…..…….37 Great Aunt Gertrude…………………………………………………………..……..…..39 The Oven…………………………………………………………………….………..…41 Father Ray…………………………………………………………………………...…..43 Running from the Law in -

Guide to Off-Road Vehicle & Equipment Regulations

Guide to Off-Road Vehicle & Equipment Regulations The California Air Resources Board (CARB) is actively enforcing off-road diesel and large spark-ignition engine vehicle and equipment regulations in support of California’s clean air goals. Enforcement of clean off-road vehicle rules provides a level playing field for those who have already done their part and are in compliance. If your fleet does not meet state clean air laws, you could be subject to fines. This booklet provides basic information and resources to help take the guesswork out of California’s clean off-road vehicle and equipment requirements. This booklet is not comprehensive of all CARB regulations that an off-road fleet may be subject to, but provides basic information specific to the following: • Regulation for In-Use Off-Road Diesel-Fueled Fleets • Large Spark-Ignition Engine Fleet Requirements Regulation • Portable Equipment Registration Program DISCLAIMER While this booklet is intended to assist vehicle owners with their compliance efforts, it is the sole responsibility of fleets to ensure compliance with applicable regulations. For more information or assistance with compliance options, visit arb.ca.gov/offroadzone, call the toll-free hotline at (877) 59DOORS (877-593-6677), or email at [email protected]. Table of Contents What off-road vehicle and equipment rules may apply to you? 1 Regulation for In-Use Off-Road Diesel-Fueled Fleets 2 Basic Reporting 3 Reporting – Initial & Annual 3 Labeling 3 Emission Performance Compliance Options 4 Meeting the Fleet Average Target -

CLASSIC SONGS (60S/70S/80S/90S)

MODERN SONGS (2000 – today) ARTIST SONG ARTIST SONG Adele Someone Like You John Mayer Waiting On The World To Change Adele Rolling In The Deep John Mayer Gravity Adele Set Fire To The Rain John Mayer Slow Dancing In A Burning Room John Mayer Stop This Train Alicia Keys If I Ain’t Got You Aloe Blacc I Need A Dollar Justin Timberlake Suit & Tie Amy Winehouse Rehab Justin Timberlake Rock Your Body Amy Winehouse Valerie Justin Timberlake Senorita Angus & Julia Stone Big Jet Plane Kings Of Leon Use Somebody Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire Beyonce Love On Top LMFAO Party Rocking Bruno Mars Just The Way You Are LMFAO Sexy And I Know It Bruno Mars Locked Out Of Heaven Maroon 5 This Love Bruno Mars Lazy Song Maroon 5 Moves Like Jagger Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Maroon 5 She Will Be Loved Cee Lo Green Forget You Maroon 5 Sunday Morning Daniel Merriweather Change Michael Buble Home David Guetta feat.Sia Titanium Michael Buble Everything David Gray The One I Love Michael Buble How Sweet It Is Ed Sheeran The A-Team Mumford & Sons The Cave Foster The People Pumped Up Kicks Mumford & Sons Little Lion Man Foster The People Call It What You Want Neyo Closer Frank Ocean Thinkin Bout You Neyo So Sick Frank Ocean Sweet Life Norah Jones Come Away With Me fun. We Are Young Norah Jones Don’t Know Why George Michael Amazing Outkast Hey Ya Gnarls Barkley Crazy Outkast Roses Gotye Heart's A Mess Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Gotye I Feel Better Pete Murray Feeler Gotye In Your Light Pete Murray So Beautiful Gotye Somebody That I Used -

Montage Setlist

Montage Setlist Take Me Back – Noiseworks Hit Me With Your Best Shot – Pat Benatar Tucker’s Daughter – Ian Moss Call Me – Blondie Cry in Shame – Diesel Sweet Child o’ Mine – Guns n Roses One Word – Baby Animals Better – Screaming Jets Don’t Stop Believing – Journey Summer of 69 – Bryan Adams Pressure Down – John Farnham Livin on a Prayer – Bon Jovi You’re the Voice – John Farnham Horses – Daryl Braithwaite Power of Love – Huey Lewis Superstition – Stevie Wonder Hip to be Square – Huey Lewis You Give Love a Bad Name – Bon Jovi Boys of Summer – Don Henley Bad Medicine – Bon Jovi Cold as Ice - Foreigner Rosanna – Toto Go Your Own Way – Fleetwood Mac Run to You – Bryan Adams Life in the Fast Lane - Eagles Jessie’s Girl – Rick Springfield Long Way to the Top – ACDC Take on Me – Aha You Shook Me All Night Long – ACDC Come on Eileen – Dexy’s Midnight Runners Africa – Toto Hold the Line – Toto Black or White – Michael Jackson Easy Lover – Phil Collins Separate Ways – Journey Poison – Alice Cooper Khe Sanh – Cold Chisel Hurt So Good – John Mellencamp Flame Trees – Cold Chisel Touch – Noiseworks Love Is – Allanah Myles Girls Just Wanna Have Fun – Cindi Lauper Get Out of My Dreams – Billy Ocean We Built This City – Starship Danger Zone – Kenny Loggins One Summer – Daryl Braithwaite Eye of the Tiger – Survivor Final Countdown – Europe Jump – Van Halen Can’t Stop This Thing – Bryan Adams Dreams – Van Halen You Make My Dreams – Hall & Oates Cheap Wine – Cold Chisel Never Gonna Give You Up – Rick Astley Run to Paradise – Choir Boys Dance With Somebody—Whitney Houston Working Class Man - Jimmy Barnes Heaven is a Place on Earth—Belinda Carlisle Black Velvet—Allanah Miles Walking on Sunshine—Katrina and the Waves www.ient.com.au Andrew Brassington | Managing Director [email protected] Mobile: 0408 445 562 | Direct: 03 6251 3118 . -

In This Issue

DOWNSIZING? SINGLE? We can help you FREE We have your partner sell and nd the MONTHLY Providing perfect new home. a personal introductions For expert advice, service for active seniors call Adrian Abel since 1995 0410 564 304 NO COMPUTER NEEDED! 9371 0380 See Friend to Friend on page 49 for Solutions Contacts Column www.solutionsmatchmaking.com.au Established 1991 PRINT POST APPROVED: 64383/00006 SUPPORTING SENIORS’ RECREATION COUNCIL OF WA (INC) WA’S PREMIER MONTHLY PAPER FOR THE OVER 45s45s VOLUME 24 NO. 12 ISSUE NO. 280 JULY 2015 • FoodIn & Wine this Issue Australia’s rock and roll - Wine for winter • Let’s Go Travelling - WIN a trip to Bali plus much more... • Downsizing • Grand Activities royalty return to Perth - School Holiday Fun by Brad Elborough THE PERTH ARENA opened late in 2012, but it Competitions/Giveaways will nally come of age in November when it plays host to Australian music royalty, Cold Chisel. You just can’t be taken seriously as a music venue in this country until the unique vocal tones of Jimmy Barnes and the beautiful guitar play- ing of Ian Moss have echoed through your halls. The Arena crowds were Peace Train - A Cat Stevens Tribute warmed up earlier this year Tommy Emmanuel when it welcomed the prin- Chris Hadfield cess of Aussie music, Kylie The Great Britain Retro Film Festival Minogue - but a Chisel con- The Audience - Helen Mirren cert is something different. Mr Holmes These guys have been Madame Bovary rocking venues, festivals Scandinavian Film Festival and major events throughout Australia (on and off) since 1973, since Kylie was ve. -

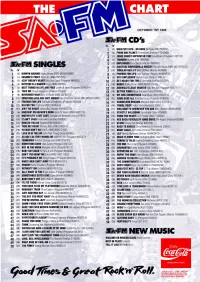

SA-FM Charts, 1992-10-01 to 1992-11-12

OCTOBER 1ST 1992 Na. LW 1 (3) GREATEST HITS - DR HOOK Dr Hook (EMI 7995052) 2 (2) FORM ONE PLANET Rockmelons (Festival TVD93360) 3 (11 JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR 1992 Soundtrack (Polygram 5137132) 4 (6) TOURISM Roxette (EMI 7999294) 5 117) UNPLUGGED Eric Clapton (Warner 9362450) 6 (5) ELECTRIC SOUP/GORILLA BISCUIT Hoodoo Gurus (BMG 432110740-2) NO. LW 7 (14) TUBULAR BELLS II Mike Oldtield (Warner 4509906) 1 (2) HUMPIN AROUND Bobby Brown (BMG MCAD518962) 8 (4) FRIENDS FOR LIFE Jose Carieras (Warner 4509902552) 2 (1) SESAME'S TREET Smart Es (BMG PDS 510) 9 (9) MTV UNPLUGGED Mariah Carey (Sony 471869 2) 3 (7) ACHY BREAKY HEART Billy Ray Cyrus (Polygram 8640562) 10 (7) GET READY FOR THIS 2 Unlimited (Festival D 30797) 4 (4) RHYTHM IS A DANCER Snap (BMG 665309) 11 (10) BOBBY Bobby Brown (BMG MCAD 10417) 5 (3) BEST THINGS IN LIFE ARE FREE Luther & Janet (Polygram 587410-4) 12 120) AMERICA'S LEAST WANTED Ugly Kid Joe (Polygram 512571-) 6 (9) TAKE ME Dream Frequency (Festival D11203) 13 (18) BETTER TIMES Black Sorrows (Sony 4721492) 7 (8) NOVEMBER RAIN Guns N' Roses (BMG GEFDS 21) 14 (8) MY GIRL SOUNDTRACK Soundtrack (Sony 469213-2) 8 (15) SOMETIMES LOVE JUST AIN'T ENOUGH Patty Smyth/Don Henley (BMG MCADS 54403) 15 (271 SOME GAVE ALL Billy Ray Cyrus (Polygram 5106352) 9 (5) FRIENDS FOR LIFE Carreras & Brightman (Polygram 863308) 16 124) CHAMELEON DREAMS Margaret Urlich (Sony 472118.2) 10 (12) DO FOR YOU Euphoria (EMI 8740054-2) 17 119) TRIBAL VOICE Yothu Yindi (Festival D 30602) 11 (21) AIN'T NO DOUBT Jimmy Nail (Warner 4509902272) 18 (11) WELCOME -

Jet Interaction in a Small-Bore Optical Diesel Engine

The shortening of lift-off length associated with jet-wall and jet- jet interaction in a small-bore optical diesel engine. Alvin M. Ruslya, Minh K. Lea, Sanghoon Kook*, a, Evatt R. Hawkesa, b, aSchool of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, The University of New South Wales, Sydney NSW 2052, Australia bSchool of Photovoltaic and Renewable Engineering, The University of New South Wales, Sydney NSW 2052, Australia * Corresponding Author: Phone: +61 2 9385 4091, Fax: +61 2 9663 1222, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Jet-wall and jet-jet interactions are important diesel combustion phenomena that impact fuel- air mixing, flame lift-off and pollutant formation. Previous studies to visualise a wall- interacting jet in heavy-duty diesel engines suggested that the shortening of lift-off length could occur due to the recirculated hot combustion products that are entrained back into incoming diesel jet. The significance of this effect, known as re-entrainment, can be higher in small-bore engines due to shorter nozzle-to-wall distance and increased wall curvature. In this study, we performed hydroxyl chemiluminescence imaging using an intensified CCD camera and high-speed imaging of natural soot luminosity using a CMOS camera in an automotive-size optical diesel engine. To provide detailed understanding of the reacting jet under the influence of re-entrainment as well as jet-jet interaction, various jet trajectories were investigated using one and two-hole injectors coupled with a modified piston that allows 1) the identification of the shortening of lift-off length, 2) the measurements of lift-off lengths for varying degrees of jet-wall interactions and 3) the clarification on inter-jet spacing effects on the lift-off lengths.