Chapter 4 Boundary Layers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4: Immersed Body Flow [Pp

MECH 3492 Fluid Mechanics and Applications Univ. of Manitoba Fall Term, 2017 Chapter 4: Immersed Body Flow [pp. 445-459 (8e), or 374-386 (9e)] Dr. Bing-Chen Wang Dept. of Mechanical Engineering Univ. of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, R3T 5V6 When a viscous fluid flow passes a solid body (fully-immersed in the fluid), the body experiences a net force, F, which can be decomposed into two components: a drag force F , which is parallel to the flow direction, and • D a lift force F , which is perpendicular to the flow direction. • L The drag coefficient CD and lift coefficient CL are defined as follows: FD FL CD = 1 2 and CL = 1 2 , (112) 2 ρU A 2 ρU Ap respectively. Here, U is the free-stream velocity, A is the “wetted area” (total surface area in contact with fluid), and Ap is the “planform area” (maximum projected area of an object such as a wing). In the remainder of this section, we focus our attention on the drag forces. As discussed previously, there are two types of drag forces acting on a solid body immersed in a viscous flow: friction drag (also called “viscous drag”), due to the wall friction shear stress exerted on the • surface of a solid body; pressure drag (also called “form drag”), due to the difference in the pressure exerted on the front • and rear surfaces of a solid body. The friction drag and pressure drag on a finite immersed body are defined as FD,vis = τwdA and FD, pres = pdA , (113) ZA ZA Streamwise component respectively. -

Brief History of the Early Development of Theoretical and Experimental Fluid Dynamics

Brief History of the Early Development of Theoretical and Experimental Fluid Dynamics John D. Anderson Jr. Aeronautics Division, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction 1 2 Early Greek Science: Aristotle and Archimedes 2 As you read these words, there are millions of modern engi- neering devices in operation that depend in part, or in total, 3 DA Vinci’s Fluid Dynamics 2 on the understanding of fluid dynamics – airplanes in flight, 4 The Velocity-Squared Law 3 ships at sea, automobiles on the road, mechanical biomedi- 5 Newton and the Sine-Squared Law 5 cal devices, and so on. In the modern world, we sometimes take these devices for granted. However, it is important to 6 Daniel Bernoulli and the Pressure-Velocity pause for a moment and realize that each of these machines Concept 7 is a miracle in modern engineering fluid dynamics wherein 7 Henri Pitot and the Invention of the Pitot Tube 9 many diverse fundamental laws of nature are harnessed and 8 The High Noon of Eighteenth Century Fluid combined in a useful fashion so as to produce a safe, efficient, Dynamics – Leonhard Euler and the Governing and effective machine. Indeed, the sight of an airplane flying Equations of Inviscid Fluid Motion 10 overhead typifies the laws of aerodynamics in action, and it 9 Inclusion of Friction in Theoretical Fluid is easy to forget that just two centuries ago, these laws were Dynamics: the Works of Navier and Stokes 11 so mysterious, unknown or misunderstood as to preclude a flying machine from even lifting off the ground; let alone 10 Osborne Reynolds: Understanding Turbulent successfully flying through the air. -

In Classical Fluid Dynamics, a Boundary Layer Is the Layer I

Atm S 547 Boundary Layer Meteorology Bretherton Lecture 1 Scope of Boundary Layer (BL) Meteorology (Garratt, Ch. 1) In classical fluid dynamics, a boundary layer is the layer in a nearly inviscid fluid next to a surface in which frictional drag associated with that surface is significant (term introduced by Prandtl, 1905). Such boundary layers can be laminar or turbulent, and are often only mm thick. In atmospheric science, a similar definition is useful. The atmospheric boundary layer (ABL, sometimes called P[lanetary] BL) is the layer of fluid directly above the Earth’s surface in which significant fluxes of momentum, heat and/or moisture are carried by turbulent motions whose horizontal and vertical scales are on the order of the boundary layer depth, and whose circulation timescale is a few hours or less (Garratt, p. 1). A similar definition works for the ocean. The complexity of this definition is due to several complications compared to classical aerodynamics. i) Surface heat exchange can lead to thermal convection ii) Moisture and effects on convection iii) Earth’s rotation iv) Complex surface characteristics and topography. BL is assumed to encompass surface-driven dry convection. Most workers (but not all) include shallow cumulus in BL, but deep precipitating cumuli are usually excluded from scope of BLM due to longer time for most air to recirculate back from clouds into contact with surface. Air-surface exchange BLM also traditionally includes the study of fluxes of heat, moisture and momentum between the atmosphere and the underlying surface, and how to characterize surfaces so as to predict these fluxes (roughness, thermal and moisture fluxes, radiative characteristics). -

Literature Review

SECTION VII GLOSSARY OF TERMS SECTION VII: TABLE OF CONTENTS 7. GLOSSARY OF TERMS..................................................................... VII - 1 7.1 CFD Glossary .......................................................................................... VII - 1 7.2. Particle Tracking Glossary.................................................................... VII - 3 Section VII – Glossary of Terms Page VII - 1 7. GLOSSARY OF TERMS 7.1 CFD Glossary Advection: The process by which a quantity of fluid is transferred from one point to another due to the movement of the fluid. Boundary condition(s): either: A set of conditions that define the physical problem. or: A plane at which a known solution is applied to the governing equations. Boundary layer: A very narrow region next to a solid object in a moving fluid, and containing high gradients in velocity. CFD: Computational Fluid Dynamics. The study of the behavior of fluids using computers to solve the equations that govern fluid flow. Clustering: Increasing the number of grid points in a region to better resolve a geometric or flow feature. Increasing the local grid resolution. Continuum: Having properties that vary continuously with position. The air in a room can be thought of as a continuum because any cube of air will behave much like any other chosen cube of air. Convection: A similar term to Advection but is a more generic description of the Advection process. Convergence: Convergence is achieved when the imbalances in the governing equations fall below an acceptably low level during the solution process. Diffusion: The process by which a quantity spreads from one point to another due to the existence of a gradient in that variable. Diffusion, molecular: The spreading of a quantity due to molecular interactions within the fluid. -

Chapter 5 Frictional Boundary Layers

Chapter 5 Frictional boundary layers 5.1 The Ekman layer problem over a solid surface In this chapter we will take up the important question of the role of friction, especially in the case when the friction is relatively small (and we will have to find an objective measure of what we mean by small). As we noted in the last chapter, the no-slip boundary condition has to be satisfied no matter how small friction is but ignoring friction lowers the spatial order of the Navier Stokes equations and makes the satisfaction of the boundary condition impossible. What is the resolution of this fundamental perplexity? At the same time, the examination of this basic fluid mechanical question allows us to investigate a physical phenomenon of great importance to both meteorology and oceanography, the frictional boundary layer in a rotating fluid, called the Ekman Layer. The historical background of this development is very interesting, partly because of the fascinating people involved. Ekman (1874-1954) was a student of the great Norwegian meteorologist, Vilhelm Bjerknes, (himself the father of Jacques Bjerknes who did so much to understand the nature of the Southern Oscillation). Vilhelm Bjerknes, who was the first to seriously attempt to formulate meteorology as a problem in fluid mechanics, was a student of his own father Christian Bjerknes, the physicist who in turn worked with Hertz who was the first to demonstrate the correctness of Maxwell’s formulation of electrodynamics. So, we are part of a joined sequence of scientists going back to the great days of classical physics. -

Chapter 4: Immersed Body Flow [Pp

MECH 3492 Fluid Mechanics and Applications Univ. of Manitoba Fall Term, 2017 Chapter 4: Immersed Body Flow [pp. 445-459 (8e), or 374-386 (9e)] Dr. Bing-Chen Wang Dept. of Mechanical Engineering Univ. of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, R3T 5V6 When a viscous fluid flow passes a solid body (fully-immersed in the fluid), the body experiences a net force, F, which can be decomposed into two components: a drag force F , which is parallel to the flow direction, and • D a lift force F , which is perpendicular to the flow direction. • L The drag coefficient CD and lift coefficient CL are defined as follows: FD FL CD = 1 2 and CL = 1 2 , (112) 2 ρU A 2 ρU Ap respectively. Here, U is the free-stream velocity, A is the “wetted area” (total surface area in contact with fluid), and Ap is the “planform area” (maximum projected area of an object such as a wing). In the remainder of this section, we focus our attention on the drag forces. As discussed previously, there are two types of drag forces acting on a solid body immersed in a viscous flow: friction drag (also called “viscous drag”), due to the wall friction shear stress exerted on the • surface of a solid body; pressure drag (also called “form drag”), due to the difference in the pressure exerted on the front • and rear surfaces of a solid body. The friction drag and pressure drag on a finite immersed body are defined as FD,vis = τwdA and FD, pres = pdA , (113) ZA ZA Streamwise component respectively. -

Part III: the Viscous Flow

Why does an airfoil drag: the viscous problem – André Deperrois – March 2019 Rev. 1.1 © Navier-Stokes equations Inviscid fluid Time averaged turbulence CFD « RANS » Reynolds Averaged Euler’s equations Reynolds equations Navier-stokes solvers irrotational flow Viscosity models, uniform 3d Boundary Layer eq. pressure in BL thickness, Prandlt Potential flow mixing length hypothesis. 2d BL equations Time independent, incompressible flow Laplace’s equation 1d BL Integral 2d BL differential equations equations 2d mixed empirical + theoretical 2d, 3d turbulence and transition models 2d viscous results interpolation The inviscid flow around an airfoil Favourable pressure gradient, the flo! a""elerates ro# $ero at the leading edge%s stagnation point& Adverse pressure gradient, the low decelerates way from the surface, the flow free tends asymptotically towards the stream air freestream uniform flow flow inviscid ◀—▶ “laminar”, The boundary layer way from the surface, the fluid’s velocity tends !ue to viscosity, the asymptotically towards the tangential velocity at the velocity field of an ideal inviscid contact of the foil is " free flow around an airfoil$ stream air flow (magnified scale) The boundary layer is defined as the flow between the foil’s surface and the thic%ness where the fluid#s velocity reaches &&' or &&$(' of the inviscid flow’s velocity. The viscous flow around an airfoil at low Reynolds number Favourable pressure gradient, the low a""elerates ro# $ero at the leading edge%s stagnation point& Adverse pressure gradient, the low decelerates +n adverse pressure gradients, the laminar separation bubble forms. The flow goes flow separates. The velocity close to the progressively turbulent inside the bubble$ surface goes negative. -

The Atmospheric Boundary Layer (ABL Or PBL)

The Atmospheric Boundary Layer (ABL or PBL) • The layer of fluid directly above the Earth’s surface in which significant fluxes of momentum, heat and/or moisture are carried by turbulent motions whose horizontal and vertical scales are on the order of the boundary layer depth, and whose circulation timescale is a few hours or less (Garratt, p. 1). A similar definition works for the ocean. • The complexity of this definition is due to several complications compared to classical aerodynamics: i) Surface heat exchange can lead to thermal convection ii) Moisture and effects on convection iii) Earth’s rotation iv) Complex surface characteristics and topography. Atm S 547 Lecture 1, Slide 1 Sublayers of the atmospheric boundary layer Atm S 547 Lecture 1, Slide 2 Applications and Relevance of BLM i) Climate simulation and NWP ii) Air Pollution and Urban Meteorology iii) Agricultural meteorology iv) Aviation v) Remote Sensing vi) Military Atm S 547 Lecture 1, Slide 3 History of Boundary-Layer Meteorology 1900 – 1910 Development of laminar boundary layer theory for aerodynamics, starting with a seminal paper of Prandtl (1904). Ekman (1905,1906) develops his theory of laminar Ekman layer. 1910 – 1940 Taylor develops basic methods for examining and understanding turbulent mixing Mixing length theory, eddy diffusivity - von Karman, Prandtl, Lettau 1940 – 1950 Kolmogorov (1941) similarity theory of turbulence 1950 – 1960 Buoyancy effects on surface layer (Monin and Obuhkov, 1954). Early field experiments (e. g. Great Plains Expt. of 1953) capable of accurate direct turbulent flux measurements 1960 – 1970 The Golden Age of BLM. Accurate observations of a variety of boundary layer types, including convective, stable and trade- cumulus. -

Incompressible Irrotational Flow

Incompressible irrotational flow Enrique Ortega [email protected] Rotation of a fluid element As seen in M1_2, the arbitrary motion of a fluid element can be decomposed into • A translation or displacement due to the velocity. • A deformation (due to extensional and shear strains) mainly related to viscous and compressibility effects. • A rotation (of solid body type) measured through the midpoint of the diagonal of the fluid element. The rate of rotation is defined as the angular velocity. The latter is related to the vorticity of the flow through: d 2 V (1) dt Important: for an incompressible, inviscid flow, the momentum equations show that the vorticity for each fluid element remains constant (see pp. 17 of M1_3). Note that w is positive in the 2 – Irrotational flow counterclockwise sense Irrotational and rotational flow ij 0 According to the Prandtl’s boundary layer concept, thedomaininatypical(high-Re) aerodynamic problem at low can be divided into outer and inner flow regions under the following considerations: Extracted from [1]. • In the outer region (away from the body) the flow is considered inviscid and irrotational (viscous contributions vanish in the momentum equations and =0 due to farfield vorticity conservation). • In the inner region the viscous effects are confined to a very thin layer close to the body (vorticity is created at the boundary layer by viscous stresses) and a thin wake extending downstream (vorticity must be convected with the flow). Under these hypotheses, it is assumed that the disturbance of the outer flow, caused by the body and the thin boundary layer around it, is about the same caused by the body alone. -

Boundary Layers

1 I-campus project School-wide Program on Fluid Mechanics Modules on High Reynolds Number Flows K. P. Burr, T. R. Akylas & C. C. Mei CHAPTER TWO TWO-DIMENSIONAL LAMINAR BOUNDARY LAYERS 1 Introduction. When a viscous fluid flows along a fixed impermeable wall, or past the rigid surface of an immersed body, an essential condition is that the velocity at any point on the wall or other fixed surface is zero. The extent to which this condition modifies the general character of the flow depends upon the value of the viscosity. If the body is of streamlined shape and if the viscosity is small without being negligible, the modifying effect appears to be confined within narrow regions adjacent to the solid surfaces; these are called boundary layers. Within such layers the fluid velocity changes rapidly from zero to its main-stream value, and this may imply a steep gradient of shearing stress; as a consequence, not all the viscous terms in the equation of motion will be negligible, even though the viscosity, which they contain as a factor, is itself very small. A more precise criterion for the existence of a well-defined laminar boundary layer is that the Reynolds number should be large, though not so large as to imply a breakdown of the laminar flow. 2 Boundary Layer Governing Equations. In developing a mathematical theory of boundary layers, the first step is to show the existence, as the Reynolds number R tends to infinity, or the kinematic viscosity ν tends to zero, of a limiting form of the equations of motion, different from that obtained by putting ν = 0 in the first place. -

Geosc 548 Notes R. Dibiase 9/2/2016

Geosc 548 Notes R. DiBiase 9/2/2016 1. Fluid properties and concept of continuum • Fluid: a substance that deforms continuously under an applied shear stress (e.g., air, water, upper mantle...) • Not practical/possible to treat fluid mechanics at the molecular level! • Instead, need to define a representative elementary volume (REV) to average quantities like velocity, density, temperature, etc. within a continuum • Continuum: smoothly varying and continuously distributed body of matter – no holes or discontinuities 1.1 What sets the scale of analysis? • Too small: bad averaging • Too big: smooth over relevant scales of variability… An obvious length scale L for ideal gases is the mean free path (average distance traveled by before hitting another molecule): = ( 1 ) 2 2 where kb is the Boltzman constant, πr is the effective4√2 cross sectional area of a molecule, T is temperature, and P is pressure. Geosc 548 Notes R. DiBiase 9/2/2016 Mean free path of atmosphere Sea level L ~ 0.1 μm z = 50 km L ~ 0.1 mm z = 150 km L ~ 1 m For liquids, not as straightforward to estimate L, but typically much smaller than for gas. 1.2 Consequences of continuum approach Consider a fluid particle in a flow with a gradient in the velocity field : �⃑ For real fluids, some “slow” molecules get caught in faster flow, and some “fast” molecules get caught in slower flow. This cannot be reconciled in continuum approach, so must be modeled. This is the origin of fluid shear stress and molecular viscosity. For gases, we can estimate viscosity from first principles using ideal gas law, calculating rate of momentum exchange directly. -

Flow Over Immerced Bodies

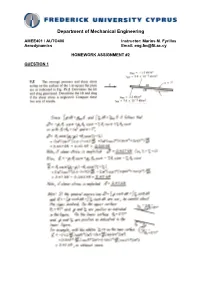

Department of Mechanical Engineering AMEE401 / AUTO400 Instructor: Marios M. Fyrillas Aerodynamics Email: [email protected] HOMEWORK ASSIGNMENT #2 QUESTION 1 Clearly there are two mechanisms responsible for the drag and the lift, the pressure and the shear stress: The drag force and the lift force on an object can be obtained by: Dpcos d Aw sin d A Lpsin d A w cos d A LIFT: Most common lift-generating devices (i.e., airfoils, fans, spoilers on cars, etc.) operate in the large Reynolds number range in which the flow has a boundary layer character, with viscous effects confined to the boundary layers and wake regions. For such cases the wall shear stress, w , contributes little to the lift. Most of the lift comes from the surface pressure distribution, as justified through Bernoulli’s equation. For objects operating in very low Reynolds number regimes (i.e. Re 1) viscous effects are important, and the contribution of the shear stress to the lift may be as important as that of the pressure. Such situations include the flight of minute insects and the swimming of microscopic organisms. DRAG: Similarly, when flow separation occurs, i.e. a blunt body or a streamlined body at a large angle of attack, the major component of the drag force is pressure differential due to the low pressure in the flow separation region. On the ultimately streamlined body (a zero thickness flat plate parallel to the flow) the drag is entirely due to the shear stress at the surface (boundary layers) and, is relatively small.