Handbook of Requirements Modeling According to the IREB Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Software Development Career Pathway

Career Exploration Guide Software Development Career Pathway Information Technology Career Cluster For more information about NYC Career and Technical Education, visit: www.cte.nyc Summer 2018 Getting Started What is software? What Types of Software Can You Develop? Computers and other smart devices are made up of Software includes operating systems—like Windows, Web applications are websites that allow users to contact management system, and PeopleSoft, a hardware and software. Hardware includes all of the Apple, and Google Android—and the applications check email, share documents, and shop online, human resources information system. physical parts of a device, like the power supply, that run on them— like word processors and games. among other things. Users access them with a Mobile applications are programs that can be data storage, and microprocessors. Software contains Software applications can be run directly from a connection to the Internet through a web browser accessed directly through mobile devices like smart instructions that are stored and run by the hardware. device or through a connection to the Internet. like Firefox, Chrome, or Safari. Web browsers are phones and tablets. Many mobile applications have Other names for software are programs or applications. the platforms people use to find, retrieve, and web-based counterparts. display information online. Web browsers are applications too. Desktop applications are programs that are stored on and accessed from a computer or laptop, like Enterprise software are off-the-shelf applications What is Software Development? word processors and spreadsheets. that are customized to the needs of businesses. Popular examples include Salesforce, a customer Software development is the design and creation of Quality Testers test the application to make sure software and is usually done by a team of people. -

Writing Quality Software

Writing Quality Software About this white paper: This whitepaper was written by David C. Young, an employee of General Dynamics Information Technology (GDIT). Dr. Young is part of a team of GDIT employees who maintain, and support high performance computing systems at the Alabama Supercomputer Center (ASC). This was written in 2020. This paper is written for people who want to write good software, but don’t have a master’s degree in software architecture (or someone managing the project who does). Much of what is here would be covered in a software development practices class, often taught at the master’s degree level. Writing quality software is not only about the satisfaction of a job well done. It is also reflects on you and your professional reputation amongst your peers. In some cases writing quality software can be a factor in getting a job, losing a job, or even life or death. Furthermore, writing quality software should be considered an implicit requirement in every software development project. If the intended useful life of the software is many years, that is yet another reason to do a good job writing it. Introduction Consider this situation, which is all too common. You have written a really neat piece of software. You put it out on github, then tell your colleagues about it. Soon you are bombarded with a series of complaints from people who tried to install, and use your software. Some of those complaints might be; • It won’t install on their version of Linux. • They did the same thing you reported, but got a different answer. -

Studying the Feasibility and Importance of Software Testing: an Analysis

Dr. S.S.Riaz Ahamed / Internatinal Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Vol.1(3), 2009, 119-128 STUDYING THE FEASIBILITY AND IMPORTANCE OF SOFTWARE TESTING: AN ANALYSIS Dr.S.S.Riaz Ahamed Principal, Sathak Institute of Technology, Ramanathapuram,India. Email:[email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Software testing is a critical element of software quality assurance and represents the ultimate review of specification, design and coding. Software testing is the process of testing the functionality and correctness of software by running it. Software testing is usually performed for one of two reasons: defect detection, and reliability estimation. The problem of applying software testing to defect detection is that software can only suggest the presence of flaws, not their absence (unless the testing is exhaustive). The problem of applying software testing to reliability estimation is that the input distribution used for selecting test cases may be flawed. The key to software testing is trying to find the modes of failure - something that requires exhaustively testing the code on all possible inputs. Software Testing, depending on the testing method employed, can be implemented at any time in the development process. Keywords: verification and validation (V & V) 1 INTRODUCTION Testing is a set of activities that could be planned ahead and conducted systematically. The main objective of testing is to find an error by executing a program. The objective of testing is to check whether the designed software meets the customer specification. The Testing should fulfill the following criteria: ¾ Test should begin at the module level and work “outward” toward the integration of the entire computer based system. -

Innovations in Natural Language Document Processing for Requirements Engineering

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Faculty and Researcher Publications Faculty and Researcher Publications 2008 Innovations in Natural Language Document Processing for Requirements Engineering Berzins, Valdis þÿB. Paech and C. Martell (Eds.): Monterey Workshop 2007, LNCS 5320, pp. 125 146, 2008. http://hdl.handle.net/10945/46073 Innovations in Natural Language Document Processing for Requirements Engineering Valdis Berzins, Craig Martell, Luqi, and Paige Adams Naval Postgraduate School, 1411 Cunningham Road, Monterey, California 93943 {berzins,cmartell,luqi,phadams}@nps.edu Abstract. This paper evaluates the potential contributions of natural language processing to requirements engineering. We present a selective history of the relationship between requirements engineering (RE) and natural-language processing (NLP), and briefly summarize relevant re- cent trends in NLP. The paper outlines basic issues in RE and how they relate to interactions between a NLP front end and system-development processes. We suggest some improvements to NLP that may be possible in the context of RE and conclude with an assessment of what should be done to improve likelihood of practical impact in this direction. Keywords: Requirements, Natural Language, Ambiguity, Gaps, Domain- Specific Methods. 1 Introduction A major challenge in requirements engineering is dealing with changes, especially in the context of systems of systems with correspondingly complex stakeholder communities and critical systems with stringent dependability requirements. Documentation driven development (DDD) is a recently developed approach for addressing these issues that seeks to simultaneously improve agility and de- pendability via computer assistance centered on a variety of documents [1,2]. The approach is based on a new view of documents as computationally active knowledge bases that support computer aid for many software engineering tasks from requirements engineering to system evolution, which is quite different from the traditional view of documents as passive pieces of paper. -

Reliability: Software Software Vs

Reliability Theory SENG 521 Re lia bility th eory d evel oped apart f rom th e mainstream of probability and statistics, and Software Reliability & was usedid primar ily as a tool to h hlelp Software Quality nineteenth century maritime and life iifiblinsurance companies compute profitable rates Chapter 5: Overview of Software to charge their customers. Even today, the Reliability Engineering terms “failure rate” and “hazard rate” are often used interchangeably. Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, University of Calgary Probability of survival of merchandize after B.H. Far ([email protected]) 1 http://www. enel.ucalgary . ca/People/far/Lectures/SENG521/ ooene MTTF is R e 0.37 From Engineering Statistics Handbook [email protected] 1 [email protected] 2 Reliability: Natural System Reliability: Hardware Natural system Hardware life life cycle. cycle. Aging effect: Useful life span Life span of a of a hardware natural system is system is limited limited by the by the age (wear maximum out) of the system. reproduction rate of the cells. Figure from Pressman’s book Figure from Pressman’s book [email protected] 3 [email protected] 4 Reliability: Software Software vs. Hardware So ftware life cyc le. Software reliability doesn’t decrease with Software systems time, i.e., software doesn’t wear out. are changed (updated) many Hardware faults are mostly physical faults, times during their e. g., fatigue. life cycle. Each update adds to Software faults are mostly design faults the structural which are harder to measure, model, detect deterioration of the and correct. software system. Figure from Pressman’s book [email protected] 5 [email protected] 6 Software vs. -

Managing Requirements Engineering Risks: an Analysis and Synthesis of the Literature

Lars Mathiassen – Timo Saarinen – Tuure Tuunanen – Matti Rossi MANAGING REQUIREMENTS ENGINEERING RISKS: AN ANALYSIS AND SYNTHESIS OF THE LITERATURE W-379 HELSINKI SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS ISSN 1795-1828 WORKING PAPERS ISBN 951-791-895-X (Electronic working paper) W-379 2004 Lars Mathiassen* – Timo Saarinen** – Tuure Tuunanen** – Matti Rossi** MANAGING REQUIREMENTS ENGINEERING RISKS: AN ANALYSIS AND SYNTHESIS OF THE LITERATURE *Center for Process Innovation, Georgia State University **Helsinki School Economics, Department of Management, Information Systems Science November 2004 HELSINGIN KAUPPAKORKEAKOULU HELSINKI SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS WORKING PAPERS W-379 HELSINGIN KAUPPAKORKEAKOULU HELSINKI SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS PL 1210 FIN-00101 HELSINKI FINLAND © Lars Mathiassen, Timo Saarinen, Tuure Tuunanen, Matti Rossi and Helsinki School of Economics ISSN 1795-1828 ISBN 951-791-895-X (Electronic working paper) Helsinki School of Economics - HeSE print 2004 Managing Requirements Engineering Risks: An Analysis and Synthesis of the Literature Lars Mathiassen ([email protected]) Center for Process Innovation, Georgia State University P. O. Box 4015, Atlanta, GA 30303-4015, USA Phone: +1-404-651-0933, Fax: +1-404-463-9292 Timo Saarinen ([email protected]) Helsinki School Economics, Department of Management, Information Systems Science P. O. Box 1210, FIN-00101 Helsinki, Finland Phone: +358-9-431-38272, Fax: Fax: +358-9-431-38700 Tuure Tuunanen ([email protected]) Helsinki School Economics, Department of Management, Information Systems Science P. O. Box 1210, FIN-00101 Helsinki, Finland Phone: +358-40-544-5591, Fax: +358-9-431-38700 http://www.tuunanen.fi Matti Rossi ([email protected]) Helsinki School Economics, Department of Management, Information Systems Science P. -

Blockchain Database for a Cyber Security Learning System

Session ETD 475 Blockchain Database for a Cyber Security Learning System Sophia Armstrong Department of Computer Science, College of Engineering and Technology East Carolina University Te-Shun Chou Department of Technology Systems, College of Engineering and Technology East Carolina University John Jones College of Engineering and Technology East Carolina University Abstract Our cyber security learning system involves an interactive environment for students to practice executing different attack and defense techniques relating to cyber security concepts. We intend to use a blockchain database to secure data from this learning system. The data being secured are students’ scores accumulated by successful attacks or defends from the other students’ implementations. As more professionals are departing from traditional relational databases, the enthusiasm around distributed ledger databases is growing, specifically blockchain. With many available platforms applying blockchain structures, it is important to understand how this emerging technology is being used, with the goal of utilizing this technology for our learning system. In order to successfully secure the data and ensure it is tamper resistant, an investigation of blockchain technology use cases must be conducted. In addition, this paper defined the primary characteristics of the emerging distributed ledgers or blockchain technology, to ensure we effectively harness this technology to secure our data. Moreover, we explored using a blockchain database for our data. 1. Introduction New buzz words are constantly surfacing in the ever evolving field of computer science, so it is critical to distinguish the difference between temporary fads and new evolutionary technology. Blockchain is one of the newest and most developmental technologies currently drawing interest. -

Geo-DB Requirement Analysis

2.1.1. Overview Lifecycle 2 Conceptual Database Design 2.1 Requirement analysis -> Text 2.2 Modeling languages Requirement analysis -> Conceptual Model 2.1.1 Overview Conceptual Design 2.1.2 Requirement Analysis (case study) 2.2.1 Basic Modeling Primitives 2.2.2 Modeling Languages: UML and CREATE TABLE Studentin (SID INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, -> Database schema VName CHAR(20) Name CHAR(30)CREATE NOT TABLENULL, Kurs Entity-Relationship Model (ERM) Logical Schema Design Email Char(40));(KID CHAR(10) PRIMARY KEY, Name CHAR(40) NOT NULL, Dauer INTEGER); CREATE TABLE Order 2.2.3 Conceptual DB design: basics ODate DATE soldBy INTEGER FOREIGN KEY REFEREBCES Peronal(PID) 2.2.4 From Requirements to Models CID INTEGER FOREIGN KEY REFERENCES Customer (CID)); Physical Schema Design -> Access paths References: Kemper / Eickler chap 2, Elmasri / Navathe chap. 3 Administration Garcia-Molina / Ullmann / Widom: chap. 2 © HS-2009 Redesign 02-DBS-Conceptual-2 Database Design:Terminology 2.1.2 Requirement Analysis Most important: talk with your customers! Def.: Database Design The process of defining the overall structure of a database, Tasks during RA: i.e. the schema, on different layers of abstraction. Identify essential "real world" information (e.g. Design levels: Conceptual, logical, physical interviews) Remove redundant, unimportant details Includes "Analysis" and "Design" from SE Clarify unclear natural language statements DB Modeling: defining the "static model" using formal or visual languages Fill remaining gaps in discussions Distinguish data and operations DB SE Requirements Requirements Conceptual modeling Analysis Requirement analysis & Conceptual Design aims at Logical modeling Design focusing thoughts and discussions ! Physical modeling Implementation © HS-2009 02-DBS-Conceptual-3 © HS-2009 02-DBS-Conceptual-4 Example: Geo-DB Requirement Analysis The database we develop will contain data about countries, cities, Clarify unclear statements organizations and geographical facts. -

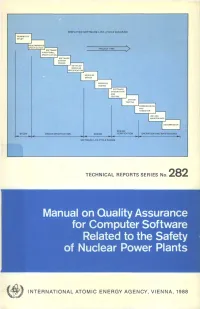

Manual on Quality Assurance for Computer Software Related to the Safety of Nuclear Power Plants

SIMPLIFIED SOFTWARE LIFE-CYCLE DIAGRAM FEASIBILITY STUDY PROJECT TIME I SOFTWARE P FUNCTIONAL I SPECIFICATION! SOFTWARE SYSTEM DESIGN DETAILED MODULES CECIFICATION MODULES DESIGN SOFTWARE INTEGRATION AND TESTING SYSTEM TESTING ••COMMISSIONING I AND HANDOVER | DECOMMISSION DESIGN DESIGN SPECIFICATION VERIFICATION OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE SOFTWARE LIFE-CYCLE PHASES TECHNICAL REPORTS SERIES No. 282 Manual on Quality Assurance for Computer Software Related to the Safety of Nuclear Power Plants f INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, VIENNA, 1988 MANUAL ON QUALITY ASSURANCE FOR COMPUTER SOFTWARE RELATED TO THE SAFETY OF NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GUATEMALA PARAGUAY ALBANIA HAITI PERU ALGERIA HOLY SEE PHILIPPINES ARGENTINA HUNGARY POLAND AUSTRALIA ICELAND PORTUGAL AUSTRIA INDIA QATAR BANGLADESH INDONESIA ROMANIA BELGIUM IRAN, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF SAUDI ARABIA BOLIVIA IRAQ SENEGAL BRAZIL IRELAND SIERRA LEONE BULGARIA ISRAEL SINGAPORE BURMA ITALY SOUTH AFRICA BYELORUSSIAN SOVIET JAMAICA SPAIN SOCIALIST REPUBLIC JAPAN SRI LANKA CAMEROON JORDAN SUDAN CANADA KENYA SWEDEN CHILE KOREA, REPUBLIC OF SWITZERLAND CHINA KUWAIT SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC COLOMBIA LEBANON THAILAND COSTA RICA LIBERIA TUNISIA COTE D'lVOIRE LIBYAN ARAB JAMAHIRIYA TURKEY CUBA LIECHTENSTEIN UGANDA CYPRUS LUXEMBOURG UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST CZECHOSLOVAKIA MADAGASCAR REPUBLIC DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA MALAYSIA UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S MALI REPUBLICS REPUBLIC OF KOREA MAURITIUS UNITED ARAB -

An Introduction to Cloud Databases a Guide for Administrators

Compliments of An Introduction to Cloud Databases A Guide for Administrators Wendy Neu, Vlad Vlasceanu, Andy Oram & Sam Alapati REPORT Break free from old guard databases AWS provides the broadest selection of purpose-built databases allowing you to save, grow, and innovate faster Enterprise scale at 3-5x the performance 14+ database engines 1/10th the cost of vs popular alternatives - more than any other commercial databases provider Learn more: aws.amazon.com/databases An Introduction to Cloud Databases A Guide for Administrators Wendy Neu, Vlad Vlasceanu, Andy Oram, and Sam Alapati Beijing Boston Farnham Sebastopol Tokyo An Introduction to Cloud Databases by Wendy A. Neu, Vlad Vlasceanu, Andy Oram, and Sam Alapati Copyright © 2019 O’Reilly Media Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com). For more infor‐ mation, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or [email protected]. Development Editor: Jeff Bleiel Interior Designer: David Futato Acquisitions Editor: Jonathan Hassell Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery Production Editor: Katherine Tozer Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest Copyeditor: Octal Publishing, LLC September 2019: First Edition Revision History for the First Edition 2019-08-19: First Release The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. An Introduction to Cloud Databases, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. The views expressed in this work are those of the authors, and do not represent the publisher’s views. -

The Roots of Software Engineering*

THE ROOTS OF SOFTWARE ENGINEERING* Michael S. Mahoney Princeton University (CWI Quarterly 3,4(1990), 325-334) At the International Conference on the History of Computing held in Los Alamos in 1976, R.W. Hamming placed his proposed agenda in the title of his paper: "We Would Know What They Thought When They Did It."1 He pleaded for a history of computing that pursued the contextual development of ideas, rather than merely listing names, dates, and places of "firsts". Moreover, he exhorted historians to go beyond the documents to "informed speculation" about the results of undocumented practice. What people actually did and what they thought they were doing may well not be accurately reflected in what they wrote and what they said they were thinking. His own experience had taught him that. Historians of science recognize in Hamming's point what they learned from Thomas Kuhn's Structure of Scientific Revolutions some time ago, namely that the practice of science and the literature of science do not necessarily coincide. Paradigms (or, if you prefer with Kuhn, disciplinary matrices) direct not so much what scientists say as what they do. Hence, to determine the paradigms of past science historians must watch scientists at work practicing their science. We have to reconstruct what they thought from the evidence of what they did, and that work of reconstruction in the history of science has often involved a certain amount of speculation informed by historians' own experience of science. That is all the more the case in the history of technology, where up to the present century the inventor and engineer have \*-as Derek Price once put it\*- "thought with their fingertips", leaving the record of their thinking in the artefacts they have designed rather than in texts they have written. -

Requirements Management Applied in an Agile Project Management Environment

Requirements Management applied in an agile Project Management environment Franco (Frank) Curtolo CEng, Principal Consultant, Program Planning Professionals Ltd, [email protected] Categorisation • Accessibility: PRACTITIONER • Application: GOOD PRACTICE • Topics: Agile Systems Engineering; Project Management Abstract This paper looks at how the Requirements Management process of Systems Engineering may benefit from some of the aspects derived from developing systems within an agile Project Management environment, using as example, the Scaled Agile Framework® of © Scaled Agile, Inc. The aim is to see if some of these agile techniques can enhance the Systems Engineering approach. Systems Engineering (SE) is well suited to develop large, complex products in a project environment where the requirements can be defined and fixed upfront. In fact, SE relies on an initial, well-defined End User’s need specified in for example, a User Requirements Specification (URS), to establish an initial requirements baseline which is used to drive the rest of the development process. However not all development projects happen that way. Sometimes the End User’s need is not clear, or cannot be well defined upfront, thus not allowing it to be captured in a fixed requirements baseline. Furthermore, the project environment may need to accommodate rapid change, both in the End Users’ need and in the technologies available to satisfy this need. In such a project environment, an agile development approach, as described in the Scaled Agile Framework® (SAFe®), may be more suitable since it allows for incremental delivery of the product and change to requirements. This can accommodate undefined End User needs, rapid change in requirements and allow for the introduction of innovation during the development and implementation stages.