Preuzmi Datoteku Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acquisizioni Fino Al 30 Giugno 2006

AUTORE/CURATORE TITOLO ANNO PRIMA PAROLA DEL TITOLO A A comme …60 fiches de pédagogie concrète 1979 A A voce alta 2002 AA.VV. Dimensioni attuali della professionalità docente 1998 AA.VV. Donne e uomini nelle guerre mondiali 1991 AA.VV. faccia scura della Luna (La) 1997 AA.VV. insegnamento delle scienze nella scuola... (L') 1981 AA.VV. legge antimafia tre anni dopo (La) 1986 AA.VV. Lessico oggi 2003 AA.VV. libro nero del comunismo (Il) 2000 AA.VV. Per conoscere la mafia 1994 AA.VV. Per una nuova cultura dell'azione educativa 1995 AA.VV. Renato Vuillermin… 1981 AA.VV. soggetti dell'autonomia (I) 1999 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 1 1997 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 2 1997 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 3 1997 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 4 1997 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 5 1997 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 6 2000 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 7 2001 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 8 1998 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 9 1999 AA.VV. Volontariato e mezzogiorno-vol. 1 1986 AA.VV. Volontariato e mezzogiorno-vol. 2 1986 AAI Politica locale dei servizi 1975 Aarts, Flor English Syntactic Structures 1982 Abastado, Claude Messages des médias 1980 Abbate, Michele alternativa meridionale (L') 1968 Abburrà, Luciano modello per l'analisi e la previsione dei flussi…(Un) 2002 Abete, Luigi Professionalità zero? 1979 Abitare Abitare la biblioteca 1984 Abraham, G. sogno del secolo (Il) 2000 Abruzzese, A. Sostiene Berlinguer 1997 Acanfora, L. Come logora insegnare 2002 Accademia di San Marciano guerra della lega di Augusta fino alla battaglia…(La) 1993 Accame, Silvio Perché la storia 1981 Accordo Accordo di revisione del Concordato Lateranense 1984 Accornero, Aris paradossi della disoccupazione (I) 1986 Acerboni, Lidia Italiano-Progetto ARCA 1995 Achenbach, C. -

William Carlos Williams' Indian Son(G)

The News from That Strange, Far Away Land: William Carlos Williams’ Indian Son(g) Graziano Krätli YALE UNIVERSITY 1. In his later years, William Carlos Williams entertained a long epistolary relationship with the Indian poet Srinivas Rayaprol (1925-98), one of a handful who contributed to the modernization of Indian poetry in English in the first few decades after the independence from British rule. The two met only once or twice, but their correspondence, started in the fall of 1949, when Rayaprol was a graduate student at Stanford University, continued long after his return to India, ending only a few years before Williams’ passing. Although Williams had many correspondents in his life, most of them more important and better known literary figures than Rayaprol, the young Indian from the southeastern state of Andhra Pradesh was one of the very few non-Americans and the only one from a postcolonial country with a long and glorious literary tradition of its own. More important, perhaps, their correspondence occurred in a decade – the 1950s – in which a younger generation of Indian poets writing in English was assimilating the lessons of Anglo-American Modernism while increasingly turning their attention away from Britain to America. Rayaprol, doubly advantaged by virtue of “being there” (i.e., in the Bay Area at the beginning of the San Francisco Renaissance) and by his mentoring relationship with Williams, was one of the very first to imbibe the new poetic idiom from its sources, and also one of the most persistent in trying to keep those sources alive and meaningful, to him if not to his fellow poets in India. -

The Development of Dylan Thomas' Use of Private Symbolism in Poetry A.Nne" Marie Delap Master of Arts

THE DEVELOPMENT OF DYLAN THOMAS' USE OF PRIVATE SYMBOLISM IN POETRY By A.NNE" MARIE DELAP \\ Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1964 ~ubmitted to the faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1967 0DAHOMI STATE IJIIVERsifi'li' 1-~BR,AYRV dlNlQN THE DEVELOPMENT OF DYLAN THOMAS O USE OF PRIVATE SYMBOLISM IN POETRY Thesis Approved: n n 11,~d Dean of the Graduate College 658670 f.i PREFACE In spite of numerous explications that have been written about Dylan Thomas' poems, there has been little attention given the growth and change in his symbolism. This study does not pretend to be comprehensive, but will atte~pt, within the areas designated by the titles of chapters 2, 3, and 4, to trace this development. The terms early 129ems and later poems will apply to the poetry finished before and after 1939, which was the year of the publication of The Map tl Love. A number of Thomas• mature poems existed in manu- script form before 1939, but were rewritten and often drastically altered before appearing in their final form. .,After the funera1° ' i is one of these: Thomas conceived the idea for the poem in 1933, but its final form, which appeared in The Map .Q! ~' represents a complete change from the early notebook version. Poem titles which appear in this study have been capitalized according to standard prac- tice, except when derived from the first line of a poem; in thes,e cases only the first word is capitalized. -

11 Ronald Mar and the Trope of Life

11 Ronald Mar and the Trope of Life The Translation of Western Modernist Poetry in Hong Kong Chris Song Abstract This essay examines the Chinese-language debut of Western surrealist poetry in Hong Kong and its effect on the local poetry scene through the work of Ronald Mar 馬朗, from the early years of the Cold War era onward. It traces the trope of poetry being “true to life” – as resistance to the surrealist influence – through evolving notions and experiences of Hong Kong identity over time, up to the present day in the post-handover era. Keywords: Chinese poetry, translation, Ronald Mar, Hong Kong, modern- ism, surrealism Twenty years since the handover of sovereignty from the British Crown to the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong society has known increasingly severe conflicts with China, fueled by animosity toward the mainland among the local population. Growing up in such a politically intense environment, Hong Kong youths feel that political and economic systems have conspired to leave them a hopeless future. As their demand for universal suffrage in the election of the Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government was denied in September 2014, their anxiety finally broke into realization as the Umbrella Movement. Apart from responding through poetry to this large democratic movement, some young local poets perceived a need to redefine the “localness” of Hong Kong poetry. Though without much theoretical depth, their quest is quite clear: they believe that the localness of their poetic language lies, paradoxically, in the distance from external reality – a symbolic denial of the Umbrella Movement’s failed demands for universal suffrage, or any further realistic democratization, in Van Crevel, Maghiel and Lucas Klein (eds.), Chinese Poetry and Translation: Rights and Wrongs. -

The Computer As Author and Artifice

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1996 Silicon poetics| The computer as author and artifice Lawrence Andrew Koch The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Koch, Lawrence Andrew, "Silicon poetics| The computer as author and artifice" (1996). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3555. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3555 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of J M O N T A N A Pennission is granted by the author to reproduce tliis material in its entirety, provided that tliis material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature D ate Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with tlie author's explicit consent. SILICON POETICS: THE COMPUTER AS AUTHOR AND ARTIFICE by Lawrence Andrew Koch B. A., Rutgers College, Rutgers University, 1991 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English (Literature option) The University of Montana 1996 Approved by: Chair, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP35509 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

DOCTORAL THESIS Stack Minimalist Poetics Davies, James

DOCTORAL THESIS stack Minimalist Poetics Davies, James Award date: 2018 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 DAVIES 1 stack: Minimalist Poetics By James Davies BA (hons), MA. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of English and Creative Writing Roehampton University 2018 DAVIES 2 Abstract stack: Minimalist Poetics consists of a portfolio of practice-led research — a volume-length minimalist poem entitled stack — and a critical essay. The poem applies and adapts several minimalist writing strategies, which are evaluated in the critical essay to create a text that is rich in imagery yet indeterminate in meaning. In addition, stack is innovative in its structural approach — through original use of enjambment, footnoting and repetition, lines may be treated as discrete entities and, also, as combinations. A key research question that the practice- led component and the critical essay interrogate is the applicability and development of the poetics of the “New Sentence”, and other formally innovative approaches in the field of minimalist writing The first part of the critical essay contextualises the creative portfolio in relation to the field of minimalist poetics as a whole. -

The Matrix of Poetry: James Schuyler's Diary

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies and the Institute of EnglishVol. 11 (Autumn Studie 2017)s, University of Warsaw Vol. 8 (2014) Special Issue Technical Innovation in North American Poetry: Form, Aesthetics, Politics Edited by Kacper Bartczak and Małgorzata Myk AMERICAN STUDIES CENTER UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 11 (Autumn 2017) Special Issue Technical Innovation in North American Poetry: Form, Aesthetics, Politics Edited by Kacper Bartczak and Małgorzata Myk Warsaw 2017 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Jacek Partyka, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWER Paulina Ambroży TYPESETTING AND GRAPHIC DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Jerzy Durczak, “Bluescape” from the series “New York City.” By permission. https://www.flickr.com/photos/jurek_durczak/ ISSN 1733–9154 Publisher Polish Association for American Studies Al. Niepodległości 22 02–653 Warsaw www.paas.org.pl Nakład: 140 egz. Printed by Sowa – Druk na życzenie phone: +48 22 431 81 40; www.sowadruk.pl Table of Contents Kacper Bartczak and Małgorzata Myk From the Editors ......................................................................................................... 271 Joanna Orska Transition-Translation: Andrzej Sosnowski’s Translation of Three Poems by John Ashbery ......................................................................................................... 275 Mikołaj Wiśniewski The Matrix of Poetry: James Schuyler’s Diary ...................................................... 295 Tadeusz Pióro Autobiography and the Politics and Aesthetics of Language Writing ............... -

Bibliography of Works Cited in from Our

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abbott, Steve. “Introduction.” Soup 2 (1981). ___. Lives of the Poets. San Francisco: Black Star Series, 1987. ___. “Notes on Boudaries: New Narrative.” Soup 4 (1985). ___. “The Philosophic Drama of Louis Zukofsky.” Poetry Flash 76 (July 1979). ___. “Wienerschnitzel.” Mirage 1 (1985). Acker, Kathy. Algeria: A Series of Invocations Because Nothing Else Works. London: Aloes Books, 1984. ___. Blood and Guts in High School. New York: Grove Press, 1978. ___. Bodies of Work. New York: Grove Press, 1997. ___. The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula by the Black Tarantula. New York: TVRT Press, 1978. ___. Don Quixote: Which Was a Dream. New York: Grove Press, 1986. ___. Empire of the Senseless. New York: Grove Press, 1988. ___. Great Expectations. New York: Grove Press, 1982. ___. “The Killers.” Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative. Eds. Mary Burger, Robert Glück, Camille Roy, and Gail Scott. Toronto: Coach House Books, 2004. ___. Portrait of an Eye: Three Novels. New York: Grove Press, 1998. ___. Pussy, King of the Pirates. New York: Grove Press, 1996. ___. “Realism for the Cause of Future Revolution.” Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation. Ed. Brian Wallis. New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1984. BIBLIOGRAPHY 329 Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess- Worshippers and Other Pagans in America. New York: Penguin, 1986. Against Expression. Eds. Craig Dworkin, Kenneth Goldsmith, and Marjorie Perloff. Evanston, IL.: Northwestern University Press, 2011. Albon, George. Aspiration. Richmond, CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2013. Alexander, Christopher W. “Looking Back on Spicer: a double-take.” Jacket 7 (1999). <http://jacketmagazine.com/07/spicer-alex.html>. -

The Necessary Experience of Error

The Necessary Experience of Error By Carla Billitteri Delirium, Hybridity, Error Carla Harryman’s work has been found “intelligent, sardonic, and elliptical to the point of delirium,” and to this list I would add picaresque and joyful (Ziolkowski n.p.). For “delirium” in its root meaning is “to go out of the furrow,” an act of wandering, of digressing, of going astray and going wrong, and one can tell from the frequency with which Harryman uses the word “delight” (etymologically, “to lure away,” to allure) that she takes joy in such delirium, in acts of writing that willingly depart from the furrows of the ordinary, the expected, the normative. Delirium manifests itself as continuous, restless movement, and it is only fitting that three of Harryman’s most recent works (The Words, Gardener of Stars, and Baby) are picaresque tales of textual errancy suffused with the delight of moving across categorical boundaries, whether of gender, space, time, or human embodiment. These movements are affirmed or reinforced compositionally by Harryman’s penchant for continuous migrations across boundaries of literary genres. Shifting swiftly and artfully from prose to poetry, from poetry to fable, from fable to drama, from drama to critical commentary, Harryman’s works are hybrid texts in Bakhtin’s sense, not fusions of genres in which new forms are created and in which old forms are changed beyond recognizability, but heterogeneous mixtures “belonging simultaneously to two or more systems” (Bakhtin 429). Through her particular approach to hybridity, Harryman demonstrates that her delight in the picaresque experience of textual errancy is not simply a crossing of genres, but of cognitive boundaries, for each literary genre defines and can in turn be defined as a 1 delineation of cognitive expectations. -

PUBLIC FOUNDATION GREATER Educational Resource DES MOINES ART TEMPLE CHESS & POETRY GARDEN by SIA ARMAJANI

PUBLIC FOUNDATION GREATER Educational Resource DES MOINES ART TEMPLE CHESS & POETRY GARDEN BY SIA ARMAJANI ABOUT THE ART AND THE ARTIST Dedicated in May 2016, this installation was a gift to the people of Des Moines by the family of Bennett Webster, an attorney who died in 2002 and who was a devotee of the game of chess. Chess is a game of deliberation, thoughtful planning, and strategy in which the two players anticipate one another’s moves and are constantly interacting with each other. Temple Chess and Poetry provides a space for both social engagement and contemplation. It is composed of multiple parts: three chess tables, a larger table for gathering around, benches, and a small garden in whose iron fence are embedded lines of poetry by Language poet Barrett Watten (b.1948), a friend of the artist. Enjoy simply sitting here quietly, talking with a friend, or bring your own chess pieces for playing the game in the thoughtful aura created by this work of public art. It is installed in an intimate space between two major buildings in downtown Des Moines: the Temple for the Performing Arts (thus, the “Temple” portion of the title) and the Des Moines Public Library. The artist highly esteems libraries as an important — and free — source of information necessary for the proper functioning of a democracy. Siah Armajani (b.1939) specializes in installations that have a strong architectural component, but with a twist: they require the viewer to become a participant. In fact, he does not consider them complete until viewers become participants and “activate” the work of art. -

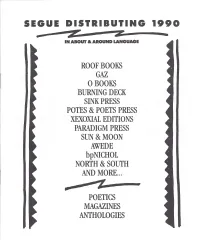

Z: • in ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE

F--~~-~- SEGUE DISTRIBUTING 1990 $5 Z z: • IN ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE ROOF BOOKS GAZ oBOOKS BURNING DECK SINK PRESS POTES & POETS PRESS XEXOXIAL EDITIONS PARADIGM PRESS SUN &MOON AWEDE bpNICHOL NORTH & SOUTH AND MORE... .......~4__.. $I I- POETICS MAGAZINES ANTHOLOGIES p--------- FEATURED PRESSES ROOF BOOKS Raik by Ray DiPalma The one hundred poems in Ray DiPalma's new collection con The Politics ofPoetic Form: Poetry andPublic Policy tinue his experiments with the poetic line that began in the early Edited by Charles Bernstein 1970s with works such as The Sargasso Transcries, Soli, and Marquee, as well as the long lyric poem Planh. Raik articulates Acollection of 14 essays by contemporary poets and critics that the dynamic variety possible within the fixed form set for each expand on the discussions presented in L=A= N= G= U= poem in the book. A= G= E, focussing on the political and ideological dimensions of the formal and stylistic practices of contemporary poetry. There is a wide range of subject matter to be found here: the lyri These essays were originally presented at the Wolfson Center for cal qualities of Elizabethan underworld slang and the contem National Affairs of the New School for Social Research in New porary urban landscape; meditations on moments in history from York. Each essay is accompanied by an edited transcript of the ancient Egypt and Roman Britain to the Italian Renaissance. discussion that took place at the New School following the initial These choices of subject spotlight DiPalma's assiduous attention presentation. to details. The word choices in each poem stir awareness of each The Politics ofPoetic Form includes full-length essays by Jerome letter in the line. -

Ron Silliman Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf696nb4f8 No online items Ron Silliman Papers Finding aid prepared by Special Collections & Archives Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, California, 92093-0175 858-534-2533 [email protected] Copyright 2005 Ron Silliman Papers MSS 0075 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Ron Silliman Papers Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0075 Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, California, 92093-0175 Languages: English Physical Description: 10.4 Linear feet(26 archives boxes) Date (inclusive): 1965-1988 Abstract: Papers of Ron Silliman, American writer and editor. Silliman has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area most of his life and is associated with the Language school of contemporary writers. He edited the anthology In The American Tree, published in 1986. The papers include extensive correspondence with many prominent contemporary writers, including Rae Armantrout, Charles Bernstein, Michael Davidson, Lyn Hejinian, Douglas Messerli, John Taggart, and Hanna Weiner. Also included are drafts of Silliman's published works, notebooks, and materials relating to In the American Tree. The collection is divided into five series: 1) ORIGINAL FINDING AID, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS, 4) IN THE AMERICAN TREE and 5) ORIGINALS OF PRESERVATION PHOTOCOPIES. Creator: Silliman, Ronald, 1946- Scope and Content of Collection The Ron Silliman papers contain collected correspondence and writings related to Silliman's career as a writer. The materials cover a range from the mid-1960s to 1988, excluding his most recent publication WHAT (1988). The collection is divided into five series: 1) ORIGINAL FINDING AID, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS, 4) IN THE AMERICAN TREE and 5) ORIGINALS OF PRESERVATION PHOTOCOPIES.