Kan Xuan: Performing the Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conversation with Hou Hanru

Michael Zheng Objectivity, Absurdity, and Social Critique: A Conversation with Hou Hanru January 12, 2009, on the occasion of the exhibition imPOSSIBLE! Eight Chinese Artists Engage Absurdity, San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery and MISSION 17 Left: Zhang Peili, WATER— I. Chinese Video Art in the 1980s Standard Version from the Dictionary Ci Hai, 1991, single- channel colour video, 9 mins. Michael Zheng: Shall we start with how video art began in China? There are 35 secs. Courtesy of the artist. quite a few video works in the exhibition imPOSSIBLE! In the West, video Middle: Zhang Peili, 30 x 30, 1988, single-channel was first used by artists to record performances and events. In that way, at colour video, 9 mins. 32 secs. Courtesy of the artist. least in the West, video art developed hand in hand with performance art. Is Right: Zhang Peili, Document the same true in China? on “Hygiene No. 3,” 1991, single-channel colour video, 24 mins. 45 secs. Courtesy of the artist. Hou Hanru: Yes, the case in China is really similar. In the 980s, when video was introduced to China as an artistic medium, it began to be used by lots of performance artists. They didn’t really have video—they had documentary, like photography, video documentaries, and very, very brief videotapes, because at that time such technology was not so popular. Only professionals had video cameras—mainly people working in television or with advertising companies. The equipment was very expensive, so few artists had access to it. One of the first artists to really use video both to document his performances and to make independent work was Zhang Peili. -

Kan Xuan 6 July – 11 September 2016

Ikon Gallery, 1 Oozells Square, Brindleyplace, Birmingham B1 2HS 0121 248 0708 / www.ikon-gallery.org Open Tuesday-Sunday, 11am-5pm / free entry Kan Xuan 6 July – 11 September 2016 Kan Xuan, Kanxuan! Ai! (1999). Video, sound, 1'22”, single channel. Film still courtesy the artist. Ikon presents the first UK exhibition by renowned Chinese artist Kan Xuan (born 1972, Anhui province). It will comprise a wide selection of single screen video pieces made since the late 1990s. Refreshingly unpretentious and economical in style, with familiar subject matter, they exemplify a profoundly philosophical approach to human existence. Kan’s work is often based on personal experience, and she herself sometimes features, as in the early video Kanxuan! Ai! (1999) in which she is seen dashing through subway tunnels shouting her own name, as if searching for herself, and then answering in the affirmative, “Ai!”. She is moving against a tide of heaving humanity, at once anxious, funny, romantic, whilst making a clear political statement, exemplifying the plight of an individual in the face of a totalitarian mass. Kan Xuan left her hometown, Xuancheng in southern Anhui province, in 1993 to study at the China Academy of Arts, Hangzhou, with influential teachers Geng Jianyi and Zhang Peili. She began working with video after arriving in Beijing in 1998, subsequently enrolling at the RijksAkademie Amsterdam where she “learned to communicate with people, not just as a person in a community, but as an artist. I learned to be more interested in other people …through [my] work.” She returned to live in Beijing in 2009. -

Chinese Contemporary Art and the Value of Dissidence by Marie

Transition and Transformation: Chinese Contemporary Art and the Value of Dissidence by Marie Dorothée Leduc A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Visual Art and Globalization Department of Sociology and Art and Design University of Alberta © Marie Leduc, 2016 Abstract Transition and Transformation: Chinese Contemporary Art and the Value of Dissidence Marie Leduc Taking an interdisciplinary approach combining sociology and art history, this dissertation considers the phenomenal rise of Chinese contemporary art in the global art market since 1989. The dissertation explores how Western perceptions of difference and dissidence have contributed to the recognition and validation of Chinese contemporary art. Guided by Nathalie Heinich’s sociology of values and Pierre Bourdieu’s work on the field of cultural production, the dissertation proposes that dissidence may be understood as an artistic value, one that distinguishes artists and artwork as singular and original. Following the careers of nine Chinese artists who moved to France in and around 1989, the dissertation demonstrates how perceptions of dissidence – artistic, cultural, and political – have distinguished Chinese artists as they have transitioned into an artistic field dominated by Western liberal-democratic values and artistic taste. The transition and transformation of Chinese contemporary art and artists then highlights how the valorization of dissidence in the West is both artistic and political, and significant to the production of contemporary art. ii Preface This thesis is an original work by Marie Leduc. The research project, of which this thesis is a part, received research ethics approval from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board, Project Name “Transition and Transformation: Contemporary Chinese Art in the Global Marketplace,” No. -

Contemporary Chinese Art

FRICK FINE ARTS LIBRARY ART HISTORY: CONTEMPORARY CHINESE ART Library Guide Series, No. 44 “Qui scit ubi scientis sit, ille est proximus habenti.” -- Brunetiere* This bibliography is highly selective and is meant only as a starting place to aid the beginning art history student in his/her search for library material. The serious student will find other relevant sources by noting citations within the encyclopedias, books, journal articles, and other sources listed below in addition to searching Pitt Cat, the ULS online catalog. IMPORTANT: For scholars who read Chinese, please note that the resources on this library guide are primarily in Western languages. Chinese language materials can be searched in Pitt Cat Classic using Pinyin. Reference assistance with Chinese language materials is available at the East Asian Library on the 2nd floor of Hillman Library. Before Beginning Research FFAL Hours: M-H, 9-9; F, 9-5; Sa-Su, Noon - 5 Policies Requesting Items: All ULS libraries allow you to request an item that is in the ULS Storage Facility or has not yet been cataloged at no charge by using the “Get It” Icon in Pitt Cat Plus. Items that are not in the Pitt library system may also be requested from another library that owns them via the same icon in the online catalog. There is a $5.00 feel for photocopying journal articles (unless they are sent to the student via email). Requesting books from another library is free of charge. Photocopying and Printing: There are two photocopiers and one printer in the FFAL Reference Room. One photocopier accepts cash (15 cents per copy) and both are equipped with a reader for the Pitt ID debit card (10 cents per copy). -

Yin Xiuzhen: Mapping the Fabric of Life

Yin Xiuzhen: Mapping the Fabric of Life A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Cynthia A. Strickland June 2009 © 2009 Cynthia A. Strickland. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Yin Xiuzhen: Mapping the Fabric of Life by CYNTHIA A. STRICKLAND has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Marion Lee Assistant Professor of the Arts Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT STRICKLAND, CYNTHIA A., M.A., June 2009, Art History Yin Xiuzhen: Mapping the Fabric of Life (90 pp.) Director ofThesis: Marion Lee This thesis examines the circumstances of production and layers of meaning in the installation works of Beijing-based contemporary artist Yin Xiuzhen (b. 1963, Beijing). The approach is to analyze several groups of Yin Xiuzhen’s installations to read how the artist has chosen to map the transformations of the economy, culture, built environment, and power structures, first of her native Beijing and then concentrically outward into the global arena. The result will chronicle the journey of the artist’s successful negotiation of place, space, materials, and message: what I call mapping the fabric of life. As an academically trained oil painter, the 1989 graduate of Capitol Normal University in Beijing initially had limited opportunities to explore a new creative path in art production. During the 1990s, she emerged along with other experimental artists in China who worked to create conceptual art. This thesis focuses on the choices both taken and resisted by Yin Xiuzhen as she developed her artistic voice and located her message within homegrown installations, using as materials fragments and remnants of lives and places. -

The Knife's Edge: Video Recently Seen in Beijing

Fremantle Arts Centre: The Knife’s Edge: video recently seen in Beijing cover: Zhao Yao, 2009 I Love Beijing 999 (series of video stills) far left: Li Ming, 2010 Pond (production still) left: Jin Shan, 2010 Not a Dream 3 from the series One Man’s Island (video still) The Knife’s Edge: video recently seen in Beijing distinctly non-narrative and non-documentary. They do not try background. For Face 11 we see Li’s face gradually appear over to illustrate aspects of reality, but rather modify and expand an hour period, as drips of water accumulate on a dark surface Their form of paradise is a heterotopic imaginary zone, our possible understandings of it. In doing so, these videos to form his reflected image. And in Face 17 the black-on-black composed of obsessions, hallucinations and quotidian manipulate the time-based qualities of the medium and present silhouette of Li’s head is occasionally made visible by him situations that need to be survived. HOU HANRU1 us with a different awareness of temporality. exhaling smoke from a cigarette. As the wisps of smoke escape Commenting on certain drives within recent Chinese art, Suturing thousands of singular moments together into a we see the brief, dissipating image of a skull hover to the left, curator Hou Hanru writes that today’s generation of artists no frenetic vision of Beijing, Zhao Yao’s I Love Beijing 999, creates and to the right the image of Li’s face. Surrounded by a black longer create consistent projections of an ideal reality. -

Art and Visual Culture in Contemporary Beijing (1978-2012)

Infrastructures of Critique: Art and Visual Culture in Contemporary Beijing (1978-2012) by Elizabeth Chamberlin Parke A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Elizabeth Chamberlin Parke 2016 Infrastructures of Critique: Art and Visual Culture in Contemporary Beijing (1978-2012) Elizabeth Chamberlin Parke Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2016 Abstract This dissertation is a story about relationships between artists, their work, and the physical infrastructure of Beijing. I argue that infrastructure’s utilitarianism has relegated it to a category of nothing to see, and that this tautology effectively shrouds other possible interpretations. My findings establish counter-narratives and critiques of Beijing, a city at once an immerging global capital city, and an urban space fraught with competing ways of seeing, those crafted by the state and those of artists. Statecraft in this dissertation is conceptualized as both the art of managing building projects that function to control Beijing’s public spaces, harnessing the thing-power of infrastructure, and the enforcement of everyday rituals that surround Beijinger’s interactions with the city’s infrastructure. From the spectacular architecture built to signify China’s neoliberal approaches to globalized urban spaces, to micro-modifications in how citizens sort their recycling depicted on neighborhood bulletin boards, the visuals of Chinese statecraft saturate the urban landscape of Beijing. I advocate for heterogeneous ways of seeing of infrastructure that releases its from being solely a function of statecraft, to a constitutive part of the artistic practices of: Song Dong (宋冬 b. -

![It Is Intended These Materials Be Downloadabkle from a Free Website]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6934/it-is-intended-these-materials-be-downloadabkle-from-a-free-website-3526934.webp)

It Is Intended These Materials Be Downloadabkle from a Free Website]

1 Contemporary Asian Art at Biennials © John Clark, 2013 Word count 37,315 words without endnotes 39,813 words including endnotes 129 pages [It is intended these materials be downloadabkle from a free website]. Asian Biennial Materials Appendix One: Some biennial reviews, including complete list of those by John Clark. 1 Appendix Two: Key Indicators for some Asian biennials. 44 Appendix Three: Funding of APT and Queensland Art Gallery. 54 Appendix Four: Report on the Database by Thomas Berghuis. 58 Appendix Five: Critics and curators active in introducing contemporary Chinese art outside China. 66 Appendix Six: Chinese artists exhibiting internationally at some larger collected exhibitions and at biennials and triennials. 68 Appendix Seven: Singapore National Education. 80 Appendix Eight: Asian Art at biennials and triennials: An Initial Bibliography. 84 Endnotes 124 2 Contemporary Asian Art at Biennials © John Clark, 2013 Appendix One: REVIEWS Contemporary Asian art at Biennales Reviews the 2005 Venice Biennale and Fukuoka Asian Triennale, the 2005 exhibition of the Sigg Collection, and the 2005 Yokohama and Guangzhou Triennales 1 Preamble If examination of Asian Biennials is to go beyond defining modernity in Asian art, we need to look at the circuits for the recognition and distribution of contemporary art in Asia. These involved two simultaneous phenomena.2 The first was the arrival of contemporary Asian artists on the international stage, chiefly at major cross-national exhibitions including the Venice and São Paolo Biennales. This may be conveniently dated to Japanese participation at Venice in the 1950s to be followed by the inclusion of three contemporary Chinese artists in the Magiciens de la terre exhibition in Paris in 1989.3 The new tendency was followed by the arrival of Chinese contemporary art at the Venice Biennale in 1993. -

Signature Redacted Signature of Author: Z/1" Department of Architecture Signature Redact Ed May.25,207 Certified By: Caroline A

CAPITALIST REALISM Making Art for Sale in Shanghai, 1999 by Xiaorui Zhu-Nowell Bachelor of Fine Arts School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2014 Submitted to the Department of Architecture In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2017 2017 Xiaorui Zhu-Nowell. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author: Z/1" Department of Architecture Signature redact ed May.25,207 Certified by: Caroline A. Jones Professor of the History of Art Department of Architecture d Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: ignature redac ted MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE t/ / Sheila Kennedy OF TECHNOLOGY Professor of Architecture Chair of the Department Committee on Graduate Students JUN 2 2 2017 LIBRARIES ARCHIVES COMMITTEE Caroline A. Jones Professor of the History of Art Department of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Lauren Jacobi Assistant Professor of the History of Art Department of Architecture Reader Rende Green Professor of Art, Culture and Technology Department of Architecture Reader CAPITALIST REALISM MakingArtfor Sale in Shanghai, 1999 by Xiaorui Zhu-Nowell Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 25, 2017 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT The artist-instigated exhibition Artfor Sale (1999), which partially operated as a fully functioning 'art supermarket' inside a large shopping mall, was one of the most important exhibitions that took place during the development of Shanghai's experimental art-scene in the 1990s, a time when the influx of consumer capitalism was becoming a key mechanism of life in the city. -

JAARVERSLAG 2013 Inhoudsopgave

Prins Hendrikkade 142 1011 at Amsterdam +31 20 625 56 51 www.deappel.nl 2013ARTISTIEK JAARVERSLAG ARTISTIEK JAARVERSLAG 2013 Inhoudsopgave 2 INLEIDING 4 TENTOONSTELLINGEN Overige presentaties en tentoonstellingen 11 NEVENACTIVITEITEN Performances Educatie Rondleidingen Zondagsschool Lezingen & debatten Boekpresentaties & events Fundraising events Curatorial Programme Research Programme Gallerist Programme Bibliotheek Archief de Appel arts centre Prins Hendrikkade 142 Bruiklenen 1011 AT Amsterdam 27 OVERZICHT MEDEWERKERS EN BESTUUR www.deappel.nl 29 SUMMARY DE APPEL ARTS CENTRE ARTISTIEK JAARVERSLAG 2013 2 Inleiding Braeckman en Zarina Bhimji en de Het jaar 2013 was het eerste volledige jaar groepstentoonstellingen Bourgeois Leftovers dat de Appel arts centre gehuisvest was (eindproject Curatorial Programme), Artificial op de nieuwe locatie, centraal gelegen in Amsterdam en de Prix de Rome. Amsterdam. Nadat 2012 een roller coaster was en met de opening van een nieuw In de solo’s van Bhimji en Braeckman Inleiding gebouw aan de Prins Hendrikkade een werden de foto’s en films van deze twee hoogtepunt markeerde in de geschiedenis internationaal gewaardeerde kunstenaars van de Appel arts centre, was 2013 een voor het eerst aan het Nederlandse publiek jaar van consolidatie en stabilisatie. De gepresenteerd. De Appel arts centre Appel arts centre heeft zich genesteld in heeft hierbij ondersteuning verleend aan haar nieuwe omgeving, kennis gemaakt de productie van nieuw werk dat bij de met de buren en de deuren opengesteld tentoonstelling een -

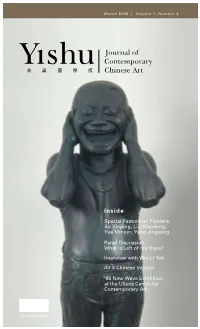

Inside Special Feature on Painters: Su Xinping, Liu Xiaodong, Yue Minjun, Yang Jingsong

March 2008 | Volume 7, Number 2 Inside Special Feature on Painters: Su Xinping, Liu Xiaodong, Yue Minjun, Yang Jingsong Panel Discussion: What is Left of the Hype? Interview with Wei-Li Yeh do it Chinese Version ’85 New Wave Exhibition at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art US$12.00 NT$350.00 1 2 3 4 10 VOLUME 7, NUMBER 2, MARCH 2008 CONTENTS Editor’s Note 25 8 Contributors Special Feature on Painters 10 Su Xinping: Allegories of Loss Jonathan Goodman 18 New Pictures of the “Ugly Chinaman:” The Art of Liu Xiaodong Thorsten Botz-Bornstein 25 Interview with Yue Minjun Karen Smith 37 New Works/New Directions in the Art of Yang Jinsong 41 Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Symposium 41 What is Left of the Hype? Panel Discussion on China’s Art: Between New Beginnings and Commerce Artist Features 57 Wang Lang and Liu Xin Hua: Mission Accomplished Mathieu Borysevicz 64 Buried Treasures: An Afternoon with Wei-Li Yeh at the Cité Internationale des Art, Paris Joni Low 64 Do It 77 Why do it Chinese Version? Hu Yuanxing interviews Hans Ulrich Obrist and Hu Fang Reviews 84 A Chinese Frequency: Vital 07 – The Essence of Performance Rachel Lois Clapham 91 Breakout: Chinese Art Outside China Jonathan Goodman 91 98 A(n) (In)Decisive Act of Disclosure: Reflections on the ‘85 New Wave Exhibition at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art in Beijing Paul Gladston 105 Chinese Name Index 98 Cover: Yue Minjun, Contemporary Terracotta Warriors (detail), 2005, bronze, 55 x 182 x 55 cm. Private Collection. Courtesy of the artist and AW ASIA, New York. -

Cui Xiuwen Born 1967 in Heilongjiang, China

Cui Xiuwen Born 1967 in Heilongjiang, China. Died 2018 in Beijing. EDUCATION 1996 M.F.A., Oil Painting Department, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing 1990 B.A., Fine Arts Department, Northeast Normal University, Jilin, China SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Cui Xiuwen: Light, Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology at Peking University, Beijing 2015 Cui Xiuwen: Awakening of the Flesh, Klein Sun Gallery, New York 2014 Cui Xiuwen: The Love of Soul, Today Art Museum, Beijing Cui Xiuwen: Reincarnation, Shanghai Gallery of Art, Shanghai 2013 Cui Xiuwen: IU - You & Me, Australia China Art Foundation Project Space, Melbourne, Australia; Suzhou Art Museum, Suzhou, China 2011 Cui Xiuwen: Discourse on Inner Humanity, Tank Loft Chongqing Contemporary Art Center, Chongqing, China Cui Xiuwen: Existential Emptiness, Eli Klein Fine Art, New York Cui Xiuwen, Blindspot Gallery, Hong Kong 2010 Cui Xiuwen: The Domain of God, Today Art Museum, Beijing Cui Xiuwen: Existential Emptiness, Tina Keng Gallery, Taipei Cui Xiuwen, Dix9 Gallery, Paris 2007 Quarter - Cui Xiuwen, Florence Museum, Florence, Italy Cui Xiuwen: Angel, Marella Gallery, Milan, Italy 2006 Cui Xiuwen, DF2 Gallery, Los Angeles Cui Xiuwen, Marella Gallery, Beijing 2005 Cui Xiuwen, Marella Gallery, Beijing 2004 Cui Xiuwen - Kan Xuan, Museum of Contemporary Art, Bordeaux, France 398 West Street, New York, NY 10014 | T: +1.212.255.4388 | [email protected] | www.galleryek.com SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2021 Right Now, Right Here, Stand by Her, Doulun Museum of Modern Art, Shanghai 2019 Art Purposes: Object Lessons for the Liberal Arts, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine Becoming - Experimental Video Works, Eli Klein Gallery, New York 2018 Intersection: International Art and Culture, Arthur M.