7.3 History of Computers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology?

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2016 Apr 28th, 9:00 AM - 10:15 AM To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology? Hayley A. LeBlanc Sunset High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y LeBlanc, Hayley A., "To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology?" (2016). Young Historians Conference. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2016/oralpres/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. To what extent did British advancements in cryptanalysis during World War 2 influence the development of computer technology? Hayley LeBlanc 1936 words 1 Table of Contents Section A: Plan of Investigation…………………………………………………………………..3 Section B: Summary of Evidence………………………………………………………………....4 Section C: Evaluation of Sources…………………………………………………………………6 Section D: Analysis………………………………………………………………………………..7 Section E: Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………10 Section F: List of Sources………………………………………………………………………..11 Appendix A: Explanation of the Enigma Machine……………………………………….……...13 Appendix B: Glossary of Cryptology Terms.…………………………………………………....16 2 Section A: Plan of Investigation This investigation will focus on the advancements made in the field of computing by British codebreakers working on German ciphers during World War 2 (19391945). -

Intro to Google for the Hill

Introduction to A company built on search Our mission Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful. As a first step to fulfilling this mission, Google’s founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin developed a new approach to online search that took root in a Stanford University dorm room and quickly spread to information seekers around the globe. The Google search engine is an easy-to-use, free service that consistently returns relevant results in a fraction of a second. What we do Google is more than a search engine. We also offer Gmail, maps, personal blogging, and web-based word processing products to name just a few. YouTube, the popular online video service, is part of Google as well. Most of Google’s services are free, so how do we make money? Much of Google’s revenue comes through our AdWords advertising program, which allows businesses to place small “sponsored links” alongside our search results. Prices for these ads are set by competitive auctions for every search term where advertisers want their ads to appear. We don’t sell placement in the search results themselves, or allow people to pay for a higher ranking there. In addition, website managers and publishers take advantage of our AdSense advertising program to deliver ads on their sites. This program generates billions of dollars in revenue each year for hundreds of thousands of websites, and is a major source of funding for the free content available across the web. Google also offers enterprise versions of our consumer products for businesses, organizations, and government entities. -

Theeccentric Engineer by Justin Pollard

106 TIME OUT COLUMNIST The name of Tommy Flowers deserves to be as well known as the computing industry giants who profited from his wartime efforts. TheEccentric Engineer by Justin Pollard PEOPLE Competition purpose machine, it was the first electronic computer. THE FORGOTTEN What are these Bletchley The device set to work on Park Wrens thinking as they Tunny intercepts. It also gained ENGINEER OF work on Colossus? The best a new name, thought up by BLETCHLEY PARK caption emailed to the members of the Women’s [email protected] by Royal Naval who operated the 23 March wins a pair of one-tonne, room-sized behemoth books from Haynes. – Colossus. A 2,400-valve version entered service four days before D-Day, providing crucial decrypts of Tunny messages in the lead-up to the invasion. It’s said system offering five trillion that Eisenhower had a Tunny times more combinations decrypt, courtesy of Colossus, than the 157 trillion offered in his hand as he gave the order by Enigma. The possibility to launch Operation Overlord. of getting bombes to crunch By the end of the war there that many permutations fast were ten Colossus machines at enough for the intelligence to Bletchley. After the surrender of have any value seemed remote. Germany, eight of them were The man charged with solving destroyed and the other two this conundrum was Max secretly moved to the peacetime Newman, whose ‘Hut F’ team was government intelligence centre, assigned the task of cracking the GCHQ, where one remained in ‘Tunny’ intercepts known to operation until 1960. -

Dr. Eric Schmidt Eric Schmidt Is Founder of Schmidt Futures

Biography of Dr. Eric Schmidt Eric Schmidt is Founder of Schmidt Futures. Eric is also Technical Advisor to Alphabet Inc., holding company of Google Inc, where he advises its leaders on technology, business and policy issues. Eric was Executive Chairman of Alphabet from 2015-2018, and of Google from 2011-2015. From 2001-2011, Eric served as Google’s Chief Executive Officer, overseeing the company’s technical and business strategy alongside founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page. Under his leadership, Google dramatically scaled its infrastructure and diversified its product offerings while maintaining a strong culture of innovation, growing from a Silicon Valley startup to a global leader in technology. Prior to joining Google, Eric was the chairman and CEO of Novell and chief technology officer at Sun Microsystems, Inc. Previously, he served on the research staff at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), Bell Laboratories and Zilog. He holds a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Princeton University as well as a master’s degree and Ph.D. in computer science from the University of California, Berkeley. Eric was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 2006 and inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as a fellow in 2007. Since 2008, he has been a trustee of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. Since 2012, Eric has been on the board of the Broad Institute and the Mayo Clinic. Eric was a member of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science 2009-2017. In 2013, Eric and Jared Cohen co-authored The New York Times bestselling book, The New Digital Age: Transforming Nations, Businesses, and Our Lives. -

Edsger Dijkstra: the Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders

INFERENCE / Vol. 5, No. 3 Edsger Dijkstra The Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders Krzysztof Apt s it turned out, the train I had taken from dsger dijkstra was born in Rotterdam in 1930. Nijmegen to Eindhoven arrived late. To make He described his father, at one time the president matters worse, I was then unable to find the right of the Dutch Chemical Society, as “an excellent Aoffice in the university building. When I eventually arrived Echemist,” and his mother as “a brilliant mathematician for my appointment, I was more than half an hour behind who had no job.”1 In 1948, Dijkstra achieved remarkable schedule. The professor completely ignored my profuse results when he completed secondary school at the famous apologies and proceeded to take a full hour for the meet- Erasmiaans Gymnasium in Rotterdam. His school diploma ing. It was the first time I met Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. shows that he earned the highest possible grade in no less At the time of our meeting in 1975, Dijkstra was 45 than six out of thirteen subjects. He then enrolled at the years old. The most prestigious award in computer sci- University of Leiden to study physics. ence, the ACM Turing Award, had been conferred on In September 1951, Dijkstra’s father suggested he attend him three years earlier. Almost twenty years his junior, I a three-week course on programming in Cambridge. It knew very little about the field—I had only learned what turned out to be an idea with far-reaching consequences. a flowchart was a couple of weeks earlier. -

Computer History – the Pitfalls of Past Futures

Research Collection Working Paper Computer history – The pitfalls of past futures Author(s): Gugerli, David; Zetti, Daniela Publication Date: 2019 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000385896 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library TECHNIKGESCHICHTE DAVID GUGERLI DANIELA ZETTI COMPUTER HISTORY – THE PITFALLS OF PAST FUTURES PREPRINTS ZUR KULTURGESCHICHTE DER TECHNIK // 2019 #33 WWW.TG.ETHZ.CH © BEI DEN AUTOREN Gugerli, Zetti/Computer History Preprints zur Kulturgeschichte der Technik #33 Abstract The historicization of the computer in the second half of the 20th century can be understood as the effect of the inevitable changes in both its technological and narrative development. What interests us is how past futures and therefore history were stabilized. The development, operation, and implementation of machines and programs gave rise to a historicity of the field of computing. Whenever actors have been grouped into communities – for example, into industrial and academic developer communities – new orderings have been constructed historically. Such orderings depend on the ability to refer to archival and published documents and to develop new narratives based on them. Professional historians are particularly at home in these waters – and nevertheless can disappear into the whirlpool of digital prehistory. Toward the end of the 1980s, the first critical review of the literature on the history of computers thus offered several programmatic suggestions. It is one of the peculiar coincidences of history that the future should rear its head again just when the history of computers was flourishing as a result of massive methodological and conceptual input. -

The Turing Approach Vs. Lovelace Approach

Connecting the Humanities and the Sciences: Part 2. Two Schools of Thought: The Turing Approach vs. The Lovelace Approach* Walter Isaacson, The Jefferson Lecture, National Endowment for the Humanities, May 12, 2014 That brings us to another historical figure, not nearly as famous, but perhaps she should be: Ada Byron, the Countess of Lovelace, often credited with being, in the 1840s, the first computer programmer. The only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, Ada inherited her father’s romantic spirit, a trait that her mother tried to temper by having her tutored in math, as if it were an antidote to poetic imagination. When Ada, at age five, showed a preference for geography, Lady Byron ordered that the subject be replaced by additional arithmetic lessons, and her governess soon proudly reported, “she adds up sums of five or six rows of figures with accuracy.” Despite these efforts, Ada developed some of her father’s propensities. She had an affair as a young teenager with one of her tutors, and when they were caught and the tutor banished, Ada tried to run away from home to be with him. She was a romantic as well as a rationalist. The resulting combination produced in Ada a love for what she took to calling “poetical science,” which linked her rebellious imagination to an enchantment with numbers. For many people, including her father, the rarefied sensibilities of the Romantic Era clashed with the technological excitement of the Industrial Revolution. Lord Byron was a Luddite. Seriously. In his maiden and only speech to the House of Lords, he defended the followers of Nedd Ludd who were rampaging against mechanical weaving machines that were putting artisans out of work. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CURVE/open How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park Smith, C Author post-print (accepted) deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Smith, C 2014, 'How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park' History of Science, vol 52, no. 2, pp. 200-222 https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0073275314529861 DOI 10.1177/0073275314529861 ISSN 0073-2753 ESSN 1753-8564 Publisher: Sage Publications Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the author’s post-print version, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer-review process. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. Mechanising the Information War – Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park Christopher Smith Abstract The Bombe machine was a key device in the cryptanalysis of the ciphers created by the machine system widely employed by the Axis powers during the Second World War – Enigma. -

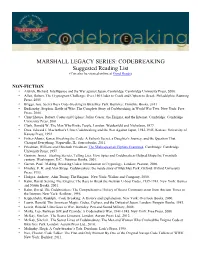

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F. L. MORRIS AND C. B. JONES The paper reproduces, with typographical corrections and comments, a 7 949 paper by Alan Turing that foreshadows much subsequent work in program proving. Categories and Subject Descriptors: 0.2.4 [Software Engineeringj- correctness proofs; F.3.1 [Logics and Meanings of Programs]-assertions; K.2 [History of Computing]-software General Terms: Verification Additional Key Words and Phrases: A. M. Turing Introduction The standard references for work on program proofs b) have been omitted in the commentary, and ten attribute the early statement of direction to John other identifiers are written incorrectly. It would ap- McCarthy (e.g., McCarthy 1963); the first workable pear to be worth correcting these errors and com- methods to Peter Naur (1966) and Robert Floyd menting on the proof from the viewpoint of subse- (1967); and the provision of more formal systems to quent work on program proofs. C. A. R. Hoare (1969) and Edsger Dijkstra (1976). The Turing delivered this paper in June 1949, at the early papers of some of the computing pioneers, how- inaugural conference of the EDSAC, the computer at ever, show an awareness of the need for proofs of Cambridge University built under the direction of program correctness and even present workable meth- Maurice V. Wilkes. Turing had been writing programs ods (e.g., Goldstine and von Neumann 1947; Turing for an electronic computer since the end of 1945-at 1949). first for the proposed ACE, the computer project at the The 1949 paper by Alan M. -

Turing's Influence on Programming — Book Extract from “The Dawn of Software Engineering: from Turing to Dijkstra”

Turing's Influence on Programming | Book extract from \The Dawn of Software Engineering: from Turing to Dijkstra" Edgar G. Daylight∗ Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract Turing's involvement with computer building was popularized in the 1970s and later. Most notable are the books by Brian Randell (1973), Andrew Hodges (1983), and Martin Davis (2000). A central question is whether John von Neumann was influenced by Turing's 1936 paper when he helped build the EDVAC machine, even though he never cited Turing's work. This question remains unsettled up till this day. As remarked by Charles Petzold, one standard history barely mentions Turing, while the other, written by a logician, makes Turing a key player. Contrast these observations then with the fact that Turing's 1936 paper was cited and heavily discussed in 1959 among computer programmers. In 1966, the first Turing award was given to a programmer, not a computer builder, as were several subsequent Turing awards. An historical investigation of Turing's influence on computing, presented here, shows that Turing's 1936 notion of universality became increasingly relevant among programmers during the 1950s. The central thesis of this paper states that Turing's in- fluence was felt more in programming after his death than in computer building during the 1940s. 1 Introduction Many people today are led to believe that Turing is the father of the computer, the father of our digital society, as also the following praise for Martin Davis's bestseller The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing1 suggests: At last, a book about the origin of the computer that goes to the heart of the story: the human struggle for logic and truth. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 2 3 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ................................................................................. 8 4 III. PARTIES .................................................................................................................... 9 5 A. Plaintiffs .......................................................................................................... 9 6 B. Defendants ....................................................................................................... 9 7 IV. FACTUAL ALLEGATIONS ................................................................................... 17 8 A. Alphabet’s Reputation as a “Good” Company is Key to Recruiting Valuable Employees and Collecting the User Data that Powers Its 9 Products ......................................................................................................... 17 10 B. Defendants Breached their Fiduciary Duties by Protecting and Rewarding Male Harassers ............................................................................ 19 11 1. The Board Has Allowed a Culture Hostile to Women to Fester 12 for Years ............................................................................................. 19 13 a) Sex Discrimination in Pay and Promotions: ........................... 20 14 b) Sex Stereotyping and Sexual Harassment: .............................. 23 15 2. The New York Times Reveals the Board’s Pattern