Chowkurlberg2020swctwoort

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics–Men's 5000M (3 Mi Before

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics –Men’s 5000m (3 mi before 1970) by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 12:56.41 Augustine Choge KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 2 2 12:58.19 Craig Mottram AUS 2 Melbourne 2006 3 3 13:05.30 Benjamin Limo KEN 3 Melbourne 2006 4 4 13:05.89 Joseph Ebuya KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 5 5 13:12.76 Fabian Joseph TAN 5 Melbourne 2006 6 6 13:13.51 Sammy Kipketer KEN 1 Manchester 2002 7 13:13.57 Benjamin Limo 2 Manchester 2002 8 7 13:14.3 Ben Jipcho KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 9 8 13.14.6 Brendan Foster GBR 2 Christchurch 1974 10 9 13:18.02 Willy Kiptoo Kirui KEN 3 Manchester 2002 11 10 13:19.43 John Mayock ENG 4 Manchester 2002 12 11 13:19.45 Sam Haughian ENG 5 Manchester 2002 13 12 13:22.57 Daniel Komen KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 14 13 13:22.85 Ian Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 15 14 13:23.00 Rob Denmark ENG 1 Victoria 1994 16 15 13:23.04 Henry Rono KEN 1 Edmonton 1978 17 16 13:23.20 Phillimon Hanneck ZIM 2 Victoria 1994 18 17 13:23.34 Ian McCafferty SCO 2 Edinburgh 1970 19 18 13:23.52 Dave Black ENG 3 Christchurch 1974 20 19 13:23.54 John Nuttall ENG 3 Victoria 1994 21 20 13:23.96 Jon Brown ENG 4 Victoria 1994 22 21 13:24.03 Damian Chopa TAN 6 Melbourne 2006 23 22 13:24.07 Philip Mosima KEN 5 Victoria 1994 24 23 13:24.11 Steve Ovett ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 25 24 13:24.86 Andrew Lloyd AUS 1 Auckland 1990 26 25 13:24.94 John Ngugi KEN 2 Auckland 1990 27 26 13:25.06 Moses Kipsiro UGA 7 Melbourne 2006 28 13:25.21 Craig Mottram 6 Manchester 2002 29 27 13:25.63 -

Messenger 2020-0708 Portrait

ST MICHAEL AND ALL ANGELS, WILLIAM STREET, HELENSBURGH July and August 2020 Charity Registered in Scotland SC006468 The United Diocese of Glasgow & Galloway Bishop: The Right Revd Kevin Pearson THE MESSENGER Diocesan Website: www.glasgow.anglican.org Clergy and Staff Rector: The Revd Dominic Ind The Rectory, 16 William Street, Helensburgh G84 8BD 01436 670297 [email protected] Lay Reader: Kevin Boak, 38 West Dhuhill Drive, Helensburgh G84 9AW 676852 [email protected] Secretary to the Vestry……………. Nick Davies The Copse, Donaldson’s Brae, Kilcreggan G84 0JB 842060 [email protected] Treasurer………………………………… Janina Duncan Deepdene, 119 West Clyde St. Helensburgh G84 8ET 0741 256 7154 [email protected] Property Convener…………………. Reay MacKay 21 Campbell Street Helensburgh G 84 8BQ 675499 [email protected] Stewardship Convener……………. Jane Davies 842060 Lay Representative…………………. Richard Horrell 676936 Children & Vulnerable ……………. Joan Thompson 423451 Persons Protection [email protected] The Magazine of Coordinator St Michael And All Angels Email: [email protected] Episcopal Church, Helensburgh Website: www.stmichaelhelensburgh.org.uk/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/stmichaelshelensburgh/ www.stmichaelhelensburgh.org.uk ST MICHAEL AND ALL ANGELS, WILLIAM STREET, HELENSBURGH July and August 2020 Charity Registered in Scotland SC006468 The United Diocese of Glasgow & Galloway Bishop: The Right Revd Kevin Pearson THE MESSENGER Diocesan Website: www.glasgow.anglican.org Clergy and Staff Rector: The Revd Dominic Ind The Rectory, 16 William Street, Helensburgh G84 8BD 01436 670297 [email protected] Lay Reader: Kevin Boak, 38 West Dhuhill Drive, Helensburgh G84 9AW 676852 [email protected] Secretary to the Vestry……………. -

Downloadable Results (Pdf)

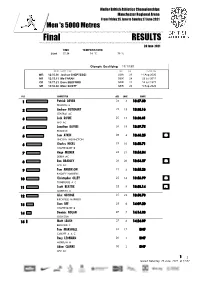

Muller British Athletics Championships Manchester Regional Arena From Friday 25 June to Sunday 27 June 2021 Men 's 5000 Metres LETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS Final RESULTS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS 26 June 2021 TIME TEMPERATURE Start 17:34 14°C 78 % Olympic Qualifying 13:13.50 MARK COMPETITOR NAT AGE Record Date WR12:35.36 Joshua CHEPTEGEI UGA 23 14 Aug 2020 NR12:53.11 Mo FARAH GBR 28 22 Jul 2011 CR13:17.21 Dave BEDFORD GBR 22 14 Jul 1972 SR13:32.98 Marc SCOTT GBR 26 5 Sep 2020 POS COMPETITOR AGE LANE MARK 1 Patrick DEVER 24 3 13:37.30 PRESTON H 2 Andrew BUTCHART 29 15 13:38.16 CENTRAL AC 3 Jack ROWE 25 13 13:38.81 AFD AC 4 Jonathan DAVIES 26 19 13:39.75 READING 5 Sam ATKIN 28 4 13:46.25 SB LINCOLN WELLINGTON 6 Charles HICKS 19 10 13:50.71 SHAFTESBURY B 7 Hugo MILNER 22 21 13:54.04 DERBY AC 8 Ben BRADLEY 26 20 13:54.37 SB AFD AC 9 Tom ANDERSON 31 5 13:55.23 BINGLEY HARRIERS 10 Christopher OLLEY 25 14 13:56.99 SB TONBRIDGE A C 11 Scott BEATTIE 22 9 13:58.14 PB MORPETH H 12 Alex GEORGE 25 22 13:58.78 BIRCHFIELD HARRIERS 13 Liam DEE 25 8 14:09.20 SHAFTESBURY B 14 Dominic NOLAN 27 7 14:14.38 CROYDON 15 Matt LEACH 27 6 14:24.09 BEDFORD C Tom MARSHALL 32 17 DNF CARDIFF A A C Rory LEONARD 20 1 DNF MORPETH H Adam CLARKE 30 2 DNF AFD AC 1 2 Issued Saturday, 26 June 2021 at 17:52 5000 Metres Men - Final RESULTS POS COMPETITOR AGE LANE MARK Ellis CROSS 24 12 DNF AFD AC David DEVINE 29 16 DNF LIVERPOOL H Mo FARAH 38 18 DNS NEWHAM E B Marc SCOTT 27 11 DNS RICHMOND & ZETLAND INTERMEDIATE TIMES 1000 228 Hugo MILNER 2:52.53 2000 228 Hugo MILNER 5:37.32 3000 228 Hugo MILNER 8:24.36 4000 89 Jonathan DAVIES 10:04.77 GREAT BRITAIN & N.I. -

Official Journal of the British Milers' Club

Official Journal of the British Milers’ Club VOLUME 3 ISSUE 14 AUTUMN 2002 The British Milers’ Club Contents . Sponsored by NIKE Founded 1963 Chairmans Notes . 1 NATIONAL COMMITTEE President Lt. CoI. Glen Grant, Optimum Speed Distribution in 800m and Training Implications C/O Army AAA, Aldershot, Hants by Kevin Predergast . 1 Chairman Dr. Norman Poole, 23 Burnside, Hale Barns WA15 0SG An Altitude Adventure in Ethiopia by Matt Smith . 5 Vice Chairman Matthew Fraser Moat, Ripple Court, Ripple CT14 8HX End of “Pereodization” In The Training of High Performance Sport National Secretary Dennis Webster, 9 Bucks Avenue, by Yuri Verhoshansky . 7 Watford WD19 4AP Treasurer Pat Fitzgerald, 47 Station Road, A Coach’s Vision of Olympic Glory by Derek Parker . 10 Cowley UB8 3AB Membership Secretary Rod Lock, 23 Atherley Court, About the Specificity of Endurance Training by Ants Nurmekivi . 11 Upper Shirley SO15 7WG BMC Rankings 2002 . 23 BMC News Editor Les Crouch, Gentle Murmurs, Woodside, Wenvoe CF5 6EU BMC Website Dr. Tim Grose, 17 Old Claygate Lane, Claygate KT10 0ER 2001 REGIONAL SECRETARIES Coaching Frank Horwill, 4 Capstan House, Glengarnock Avenue, E14 3DF North West Mike Harris, 4 Bruntwood Avenue, Heald Green SK8 3RU North East (Under 20s)David Lowes, 2 Egglestone Close, Newton Hall DH1 5XR North East (Over 20s) Phil Hayes, 8 Lytham Close, Shotley Bridge DH8 5XZ Midlands Maurice Millington, 75 Manor Road, Burntwood WS7 8TR Eastern Counties Philip O’Dell, 6 Denton Close, Kempston MK Southern Ray Thompson, 54 Coulsdon Rise, Coulsdon CR3 2SB South West Mike Down, 10 Clifton Down Mansions, 12 Upper Belgrave Road, Bristol BS8 2XJ South West Chris Wooldridge, 37 Chynowen Parc, GRAND PRIX PRIZES (Devon and Cornwall) Cubert TR8 5RD A new prize structure is to be introduced for the 2002 Nike Grand Prix Series, which will increase Scotland Messrs Chris Robison and the amount that athletes can win in the 800m and 1500m races if they run particular target times. -

The Mammoth Cave ; How I

OUTHBERTSON WHO WAS WHO, 1897-1916 Mails. Publications : The Mammoth Cave ; D'ACHE, Caran (Emmanuel Poire), cari- How I found the Gainsborough Picture ; caturist b. in ; Russia ; grandfather French Conciliation in the North of Coal ; England ; grandmother Russian. Drew political Mine to Cabinet ; Interviews from Prince cartoons in the "Figaro; Caran D'Ache is to Peasant, etc. Recreations : cycling, Russian for lead pencil." Address : fchological studies. Address : 33 Walton Passy, Paris. [Died 27 Feb. 1909. 1 ell Oxford. Club : Koad, Oxford, Reform. Sir D'AGUILAR, Charles Lawrence, G.C.B ; [Died 2 Feb. 1903. cr. 1887 ; Gen. b. 14 (retired) ; May 1821 ; CUTHBERTSON, Sir John Neilson ; Kt. cr, s. of late Lt.-Gen. Sir George D'Aguilar, 1887 ; F.E.I.S., D.L. Chemical LL.D., J.P., ; K.C.B. d. and ; m. Emily, of late Vice-Admiral Produce Broker in Glasgow ; ex-chair- the Hon. J. b. of of School Percy, C.B., 5th Duke of man Board of Glasgow ; member of the Northumberland, 1852. Educ. : Woolwich, University Court, Glasgow ; governor Entered R. 1838 Mil. Sec. to the of the Glasgow and West of Scot. Technical Artillery, ; Commander of the Forces in China, 1843-48 ; Coll. ; b. 13 1829 m. Glasgow, Apr. ; Mary served Crimea and Indian Mutiny ; Gen. Alicia, A. of late W. B. Macdonald, of commanding Woolwich district, 1874-79 Rammerscales, 1865 (d. 1869). Educ. : ; Lieut.-Gen. 1877 ; Col. Commandant School and of R.H.A. High University Glasgow ; Address : 4 Clifton Folkestone. Coll. Royal of Versailles. Recreations: Crescent, Clubs : Travellers', United Service. having been all his life a hard worker, had 2 Nov. -

Catherine Fox Was Educated at Durham and London Universities

Catherine Fox was educated at Durham and London Universities. She is the author of three adult novels: Angels and Men, The Benefits of Passion and Love for the Lost; a Young Adult fantasy novel, Wolf Tide; and a memoir, Fight the Good Fight: From vicar’s wife to killing machine, which relates her quest to achieve a black belt in judo. She lives in Liverpool, where her husband is dean of the cathedral. ‘A delightful portrait of the follies and foibles in a contemporary Anglican diocese, written with wit, wisdom and impeccable liberal sympathies.’ Michael Arditti, author and critic ‘Clear-eyed, moving and mischievously funny, Acts and Omissions is at one with the deep linguistic and human resources that make the modern Church of England what it is. The novel brims with wit and heart, acknow- ledging the awkwardness and consolations of Anglicanism in the twenty-first century. Hugely entertaining and highly recommended.’ Richard Beard, author of Lazarus is Dead ‘Catherine Fox writes so well about the Church of England that she can make sense of a world in which the salacious and the sacred are intimately entwined. This is a novelist who is never frightened to enter ecclesiastical territory where bishops fear to tread. She writes not merely with affection but with love for an institution that is creaking under the weight of its own contradictions. ‘Acts and Omissions will help people in the Church who already pray for one another daily to like one another a little more. It is also a great collection of intertwining stories that throw a welcome ray of light for those who find it hard to understand why an institution made up of good, caring people has become better known for hypocrisy than for happiness. -

Teen Sensation Athing Mu

• ALL THE BEST IN RUNNING, JUMPING & THROWING • www.trackandfieldnews.com MAY 2021 The U.S. Outdoor Season Explodes Athing Mu Sets Collegiate 800 Record American Records For DeAnna Price & Keturah Orji T&FN Interview: Shalane Flanagan Special Focus: U.S. Women’s 5000 Scene Hayward Field Finally Makes Its Debut NCAA Formchart Faves: Teen LSU Men, USC Women Sensation Athing Mu Track & Field News The Bible Of The Sport Since 1948 AA WorldWorld Founded by Bert & Cordner Nelson E. GARRY HILL — Editor JANET VITU — Publisher EDITORIAL STAFF Sieg Lindstrom ................. Managing Editor Jeff Hollobaugh ................. Associate Editor BUSINESS STAFF Ed Fox ............................ Publisher Emeritus Wallace Dere ........................Office Manager Teresa Tam ..................................Art Director WORLD RANKINGS COMPILERS Jonathan Berenbom, Richard Hymans, Dave Johnson, Nejat Kök SENIOR EDITORS Bob Bowman (Walking), Roy Conrad (Special AwaitsAwaits You.You. Projects), Bob Hersh (Eastern), Mike Kennedy (HS Girls), Glen McMicken (Lists), Walt Murphy T&FN has operated popular sports tours since 1952 and has (Relays), Jim Rorick (Stats), Jack Shepard (HS Boys) taken more than 22,000 fans to 60 countries on five continents. U.S. CORRESPONDENTS Join us for one (or more) of these great upcoming trips. John Auka, Bob Bettwy, Bret Bloomquist, Tom Casacky, Gene Cherry, Keith Conning, Cheryl Davis, Elliott Denman, Peter Diamond, Charles Fleishman, John Gillespie, Rich Gonzalez, Ed Gordon, Ben Hall, Sean Hartnett, Mike Hubbard, ■ 2022 The U.S. Nationals/World Champion- ■ World Track2023 & Field Championships, Dave Hunter, Tom Jennings, Roger Jennings, Tom ship Trials. Dates and site to be determined, Budapest, Hungary. The 19th edition of the Jordan, Kim Koffman, Don Kopriva, Dan Lilot, but probably Eugene in late June. -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J. -

A (Very Personal) History of Barnet and District AC

A (very personal) history of Barnet and District AC In early 2017 the club magazine Editor wrote to me, saying: “I'd like there to be some things in the next issue relating to the club's 50 anniversary/history etc. Would you be able/willing to contribute something?” Without hesitation I said yes, and here it is. I have chosen to write three parallel intertwined stories. They are the main points in the development of the club in the early years, illustrated with some results and reports from those days from the relevant club magazines, and interspersed with some observations on my own short running career once I arrived on the scene (thankfully for you that was not until 1982!). There are thousands of results and reports, and I have tried to select items of interest and/or relevance. I have tried to not dwell on, or comment too often on, the ‘but things were different/better in them days’ aspect of athletics. I leave you to interpret the content as you wish. Considerable license has been taken in editing down mag reports to their core detail. STEVE CHILTON (with thanks to Brian Fowler and all the club magazine editors) 1 Early days Barnet and District AC was formed in 1967, after a merger of Hampstead Harriers with Barnet AC. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find copies of the club mags from the years before 1974, so the first 6 years are something of a mystery (I copied all Brian Strong’s club mags from 1973 onwards a while ago, at the time I was editor, as he was editor for many of the early years). -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

Cyprianlife November 2014

Cyprian Remembrance Sunday 9th November 2014 Christmas Fayre Saturday 22nd November 2014 from 10am to 3pm The Magazine of St Cyprian’s Church,1 Lenzie November 2014 Scottish Episcopal Church Vestry Rector@ Revd. Les Ireland Diocese of Glasgow & Galloway Lay Representative@ Paul Hindle Bishop: 40 Garngaber Avenue, Lenzie G66 4LL ) The Right Revd. Dr. Gregor Duncan 776 3237 Bishop’s Office, Diocesan Centre Secretary@ Mary Boyd, 9 Northbank Road, ) 5 St Vincent Pl., Glasgow G1 2DH Kirkintilloch, G66 1EZ 776 2812 ) 0141-221 6911 fax 0141-221 6490 Treasurer@ Jacqui Stother, email: [email protected] 11 Fern Avenue, Lenzie G66 4LE ) 776 5330 Property Convenor@ Adrian Clark, Solsgirth Lodge, Langmuir Road, Kirkintilloch G66 3XN ) 776 2160 Elected Members Jacqui Barker, Pam Cyprian Bently, Eileen Ferry, Aileen Mundy, Dave Parfitt, Jill Taylor, Kevin Wilbraham Contacts Fundraising Group@ Susan Frost 776 4135 The News Magazine of /Kathryn Potts 578 0734 St. Cyprian’s Scottish Episcopal Church, Altar Guild@ Anne Carswell 776 3354 Beech Road, Lenzie, Glasgow. G66 4HN Alt. Lay Rep Adrian Clark 776 2160 Scottish Charity No. SC003826 Bible Rdg Fellowship Eric Parry 776 6422 The Scottish Episcopal Church is in full Fair Trade@ Vivienne Parry 776 6422 communion with the Church of England and Gift Aid@ Aileen Mundy 578 9449 all other churches of the Anglican Hall Bookings@ Gavin Boyd 776 2812 Communion throughout the world Link@ Rector 776 3866 Magazine@ Paul Hindle 776 3237 MU@ Maxine Gow 01360 Rector 310420 Revd. Les Ireland Pastoral Visiting@ -

A27 Arundel Bypass Barn Owl Baseline Survey

A27 Arundel Bypass Barn Owl Baseline Survey Appendix 8-4: Barn Owl Baseline Survey Report 06 August 2019 Appendix 8-4: Barn Owl Baseline Survey Report A27 Arundel Bypass – PCF Stage 2 Further Consultation Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 1 Introduction 1-1 1.1 Project Background 1-1 1.2 Ecological Background 1-2 1.3 Aims and Objectives 1-4 2 Methods 2-6 2.1 Study Area 2-6 2.2 Desk Study 2-6 2.3 Field Survey 2-7 2.4 Assumptions and Limitations 2-10 3 Results 3-12 3.1 Desk Study 3-12 3.2 Field Survey 3-12 4 Discussion and Recommendations 4-15 4.1 Discussion 4-15 4.2 Further Survey Recommendations 4-16 LIST OF TABLES Table 3-1 - Foraging habitat 3-13 Table 3-2 - Barn owl evidence recorded 3-14 Table 3-3 - Barn owl breeding and resting sites 3-14 August 2019 Appendix 8-4: Barn Owl Baseline Survey Report A27 Arundel Bypass – PCF Stage 2 Further Consultation Executive Summary WSP was commissioned by Highways England to undertake studies of barn owl to inform A27 Arundel Bypass Scheme Project Control Framework Stage 2. A desk study was undertaken to identify habitats suitable for this species within the area of the Scheme options. Desk study records identified multiple records of barn owl from the past 10 years within 1.5 kilometres of the Scheme options. Inspection of aerial photography identified 71 habitat features including 21 buildings potentially suitable for use by this species. Barn owl Stage 1 and 2 surveys were undertaken in 2017.