China's Integration Into the Global Financial System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Public Banks and People's Bank of China: Confronting

Chapter 13 Godfrey Yeung THE PUBLIC BANKS AND PEOPLE’S BANK OF CHINA: CONFRONTING COVID-19 (IF NOT WITHOUT CONTROVERSY) he outbreak of Covid-19 in Wuhan and its subsequent dom- ino effects due to the lock-down in major cities have had a devastating effect on the Chinese economy. China is an Tinteresting case to illustrate what policy instruments the central bank can deploy through state-owned commercial banks (a form of ‘hybrid’ public banks) to buffer the economic shock during times of crisis. In addition to the standardized practice of liquidity injection into the banking system to maintain its financial viability, the Chi- nese central bank issued two top-down and explicit administra- tive directives to state-owned commercial banks: the minimum quota on lending to small- and medium-sized enterprises (MSEs) and non-profitable lending. Notwithstanding its controversy on loopholes related to such lending practices, these pro-active policy directives provide counter-cyclical lending and appear able to pro- vide short-term relief for SMEs from the Covid-19 shock in a timely manner. This has helped to mitigate the devastating impacts of the pandemic on the Chinese economy. 283 Godfrey Yeung INTRODUCTION The outbreak of Covid-19 leading to the lock-down in Wuhan on January 23, 2020 and the subsequent pandemic had significant im- pacts on the Chinese economy. China’s policy response regarding the banking system has helped to mitigate the devastating impacts of pandemic on the Chinese economy. Before we review the measures implemented by the Chinese gov- ernment, it is important for us to give a brief overview of the roles of two major group of actors (institutions) in the banking system. -

China Construction Bank 2018 Reduced U.S. Resolution Plan Public Section

China Construction Bank 2018 Reduced U.S. Resolution Plan Public Section 1 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Overview of China Construction Bank Corporation ...................................................................................... 3 1. Material Entities .................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Core Business Lines ............................................................................................................................... 4 3. Financial Information Regarding Assets, Liabilities, Capital and Major Funding Sources .................... 5 3.1 Balance Sheet Information ........................................................................................................... 5 3.2 Major Funding Sources ................................................................................................................. 8 3.3 Capital ........................................................................................................................................... 8 4. Derivatives Activities and Hedging Activities ........................................................................................ 8 5. Memberships in Material Payment, Clearing and Settlement Systems ............................................... 8 6. Description of Foreign Operations ....................................................................................................... -

World Bank: Roadmap for a Sustainable Financial System

A UN ENVIRONMENT – WORLD BANK GROUP INITIATIVE Public Disclosure Authorized ROADMAP FOR A SUSTAINABLE FINANCIAL SYSTEM Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized NOVEMBER 2017 UN Environment The United Nations Environment Programme is the leading global environmental authority that sets the global environmental agenda, promotes the coherent implementation of the environmental dimension of sustainable development within the United Nations system and serves as an authoritative advocate for the global environment. In January 2014, UN Environment launched the Inquiry into the Design of a Sustainable Financial System to advance policy options to deliver a step change in the financial system’s effectiveness in mobilizing capital towards a green and inclusive economy – in other words, sustainable development. This report is the third annual global report by the UN Environment Inquiry. The first two editions of ‘The Financial System We Need’ are available at: www.unep.org/inquiry and www.unepinquiry.org. For more information, please contact Mahenau Agha, Director of Outreach ([email protected]), Nick Robins, Co-director ([email protected]) and Simon Zadek, Co-director ([email protected]). The World Bank Group The World Bank Group is one of the world’s largest sources of funding and knowledge for developing countries. Its five institutions share a commitment to reducing poverty, increasing shared prosperity, and promoting sustainable development. Established in 1944, the World Bank Group is headquartered in Washington, D.C. More information is available from Samuel Munzele Maimbo, Practice Manager, Finance & Markets Global Practice ([email protected]) and Peer Stein, Global Head of Climate Finance, Financial Institutions Group ([email protected]). -

2017Annual Report CONTENTS

(A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) Stock Code: 6066 2017 Annual2017 Report 2017Annual Report CONTENTS Definitions ................................ 2 Chairman’s Statement ....................... 6 Section 1 Important Notice ................. 9 Section 2 Material Risk Factors ............. 10 Section 3 Company Information ............. 11 Section 4 Financial Summary ............... 26 Section 5 Management Discussion and Analysis .................... 32 Section 6 Report of Directors ............... 84 Section 7 Other Significant Events ........... 96 Section 8 Changes in Shares and Information on Substantial Shareholders .......... 108 Section 9 Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Employees ....... 114 Section 10 Corporate Governance Report ...... 150 Section 11 Environmental, Social and Governance Report ............... 177 Annex Independent Auditor’s Report and Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements ..................... 205 Annual Report 2017 1 DEFINITIONS Unless the context otherwise requires, the following expressions have the following meanings in this annual report: “A Share(s)” the ordinary shares with a nominal value of RMB1.00 each proposed to be issued by the Company under the A Share Offering, to be listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange and traded in RMB “A Share Offering” the proposed initial public offering of not more than 400,000,000 A Shares in the PRC by the Company “Articles of Association” or “Articles” the articles of association of CSC Financial -

US and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 Eric Helleiner University of Wate

Still an Extraordinary Power After All These Years: US and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 Eric Helleiner University of Waterloo June 2014 Acknowledgements: I am grateful for comments from Randy Germain and Herman Schwartz. Parts of this paper are drawn from Helleiner 2014. I am grateful to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for helping to fund this research. Susan Strange is well known for her interventions into discussions about the trajectory of US hegemony. At a time when scholars fiercely debated the consequences of declining US hegemony, she questioned the underlying assumption being made. Scholars across the theoretical spectrum, she argued, failed to recognize the enduring nature of the US power, particularly in its structural form. She argued that scholars of international political economy often neglected the significance of structural power which she defined as “the power to shape and determine the structures of the global political economy within which other states, their political institutions, their economic enterprises, and (not least) their scientists and other professional people have to operate.”1 Strange was particularly keen to highlight the importance of enduring US structural power in the global financial arena where she argued that outcomes continued to be influenced by the unmatched ability of the US to control and shape the environment within which others operated.2 Strange’s concept of structural power has been sometimes criticized for its lack of precision.3 How is structural power exercised and over whom? What are its sources? What can it accomplish? These kinds of analytical questions were not always addressed in great detail in Strange’s writings. -

Inward Remittance — Quick Reference Guide

Inward Remittance — Quick Reference Guide How to instruct a Remitting Bank to remit funds to your account with BOCHK Please instruct the Remitting Bank to send a detailed payment instruction in SWIFT MT103 format to us using the below SWIFT BIC of BOCHK. To designate BOCHK as the Beneficiary’s bank, please provide below details. SWIFT BIC: BKCHHKHHXXX Bank Name: BANK OF CHINA (HONG KONG) LIMITED, HONG KONG Main Address: BANK OF CHINA TOWER, 1 GARDEN ROAD, CENTRAL, HONG KONG Bank Code: 012 (for local bank transfer CHATS / RTGS only) Please provide details of your account for depositing the remittance proceeds. Beneficiary’s Account Number: Please provide the 14-digit account number to deposit the incoming funds. (Please refer to Part 3 for further explanation.) Beneficiary’s Name: Please provide the name of the above account number as in our record. Major Clearing Arrangement and Correspondent Banks of BOCHK CCY SWIFT BIC Name of Bank Details Bank of China (Hong Kong) Ltd - RMB BKCHHKHH838 BOCHK’s CNAPS No.: 9895 8400 1207 Clearing Centre CNY BKCHCNBJXXX Bank of China Head Office, Beijing Direct Participant of CIPS (Payment through CIPS) BKCHCNBJS00 Bank of China, Shanghai Correspondent Bank of BOCHK in the mainland CCY SWIFT BIC Name of Bank CCY SWIFT BIC Name of Bank AUD BKCHAU2SXXX Bank of China, Sydney NOK DNBANOKKXXX DNB Bank ASA, Oslo Bank Islam Brunei Darussalam NZD BND BIBDBNBBXXX ANZBNZ22XXX ANZ National Bank Ltd, Wellington Berhad CAD BKCHCATTXXX Bank of China (Canada), Toronto SEK NDEASESSXXX Nordea Bank AB (Publ), Stockholm CHF UBSWCHZH80A UBS Switzerland AG, Zurich SGD BKCHSGSGXXX Bank of China, Singapore DKK DABADKKKXXX Danske Bank A/S, Copenhagen THB BKKBTHBKXXX Bangkok Bank Public Co Ltd, Bangkok Commerzbank AG, Frankfurt AM COBADEFFXXX CHASUS33XXX JPMorgan Chase Bank NA, New York EUR Main BKCHDEFFXXX Bank of China, Frankfurt USD CITIUS33XXX Citibank New York GBP BKCHGB2LXXX Bank of China, London BOFAUS3NXXX Bank of America, N.A. -

Circular of the Beijing Municipal Finance Bureau on Strengthening Financial Services to Support the Prevention and Control of the COVID-19 Epidemic 56

For Foreign-invested Enterprises in Beijing Municipality Compilation of Support Policies for Enterprises in Beijing Municipality During the COVID-19 Epidemic Beijing Municipal Commerce Bureau Contents Circular of the General Office of the Ministry of Commerce on Proactively Responding to the COVID-19 Epidemic, Strengthening Services for Foreign-invested Enterprises and Enhancing Investment Promotion 5 Circular of the General Office of the People's Government of Beijing Municipality on Releasing the Measures for Further Supporting Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises to Mitigate the Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic and Maintain Stable Development 8 Measures for Further Supporting Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises to Mitigate the Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic and Maintain Stable Development 9 Circular of the General Office of the People's Government of Beijing Municipality on Issuing the Measures for Preventing and Controlling the COVID-19 Epidemic and Ensuring the Safe and Orderly Resumption of Work and Production by Enterprises 14 Measures for Preventing and Controlling the COVID-19 Epidemic and Ensuring the Safe and Orderly Resumption of Work and Production by Enterprises 14 Measures of the General Office of the People's Government of Beijing Municipality for Further Supporting the Efforts to Defeat the COVID-19 Epidemic 19 Measures of the General Office of the People's Government of Beijing Municipality for Mitigating the Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic, and Supporting Sustained and Healthy Development of Micro, Small -

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Annual Report CONTENTS

2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 annual report Details of Changes in Ordinary Shares and Shareholders 90 SECTION VI Significant Events 74 SECTION V 2 6 8 Discussion and Analysis of Operations 27 SECTION IV Financial Highlights 22 SECTION III Company Profile 11 SECTION II Definitions 9 MESSAGE FROM CHAIRMAN FROM MESSAGE PRESIDENT FROM MESSAGE NOTICE IMPORTANT CONTENTS SECTION I Auditor’s Report 124 Written Confirmation of 2020 Annual Report by Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management Members of Hua Xia Bank Co., Limited 122 List of Documents for Inspection 121 SECTION XI Financial Statements 120 SECTION X Corporate Governance 112 SECTION IX Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management Members, Other Employees and Branches 100 SECTION VIII Preference Shares 96 SECTION VII 2 HUA XIA BANK CO., LIMITED MESSAGE FROM CHAIRMAN Chairman: Li Minji 2020 Annual Report 3 2020 was an extraordinary year. In a strategic In the persistent pursuit of development, we drive for great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation amid achieved new breakthroughs in reform and innovation seismic changes not seen for a century, China carried during the past four years. We insisted on driving out COVID-19 prevention and control and pursued business development with reform and innovation economic and social development in a coordinated and made solid progress in key reform tasks such way. The country successfully met challenges posed as the comprehensive risk management system, the by both the complicated international situation and operation management system and the resource the COVID-19 pandemic, securing a decisive victory allocation mechanism, which delivered gratifying in finishing the building of a moderately prosperous results. -

List of CMU Members 2021-08-18

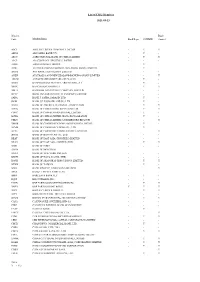

List of CMU Members 2021-09-23 Member Bond Code Member Name Bank Repo CMUBID Connect ABCI ABCI SECURITIES COMPANY LIMITED - Y Y ABNA ABN AMRO BANK N.V. - Y - ABOC AGRICULTURAL BANK OF CHINA LIMITED - Y Y AIAT AIA COMPANY (TRUSTEE) LIMITED - - - ASBK AIRSTAR BANK LIMITED - Y - ACRL ALLIED BANKING CORPORATION (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y - ANTB ANT BANK (HONG KONG) LIMITED - - - ANZH AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BANKING GROUP LIMITED - - Y AMCM AUTORIDADE MONETARIA DE MACAU - Y - BEXH BANCO BILBAO VIZCAYA ARGENTARIA, S.A. - Y - BSHK BANCO SANTANDER S.A. - Y Y BBLH BANGKOK BANK PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED - - - BCTC BANK CONSORTIUM TRUST COMPANY LIMITED - - - SARA BANK J. SAFRA SARASIN LTD - Y - JBHK BANK JULIUS BAER AND CO. LTD. - Y - BAHK BANK OF AMERICA, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION - Y Y BCHK BANK OF CHINA (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y Y CDFC BANK OF CHINA INTERNATIONAL LIMITED - Y - BCHB BANK OF CHINA LIMITED, HONG KONG BRANCH - Y - CHLU BANK OF CHINA LIMITED, LUXEMBOURG BRANCH - - Y BMHK BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y - BCMK BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS CO., LTD. - Y - BCTL BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS TRUSTEE LIMITED - - Y DGCB BANK OF DONGGUAN CO., LTD. - - - BEAT BANK OF EAST ASIA (TRUSTEES) LIMITED - - - BEAH BANK OF EAST ASIA, LIMITED (THE) - Y Y BOIH BANK OF INDIA - - - BOFM BANK OF MONTREAL - - - BNYH BANK OF NEW YORK MELLON - - - BNSH BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA (THE) - - - BOSH BANK OF SHANGHAI (HONG KONG) LIMITED - Y Y BTWH BANK OF TAIWAN - Y - SINO BANK SINOPAC, HONG KONG BRANCH - - Y BPSA BANQUE PICTET AND CIE SA - - - BBID BARCLAYS BANK PLC - Y - EQUI BDO UNIBANK, INC. -

2020 Annual Report 9668

渤海銀行股份有限公司 CHINA BOHAI BANK CO., LTD. (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) Stock Code : 9668 CHINA BOHAI BANK CO., LTD. CO., CHINA BOHAI BANK 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT Annual Report 2020 Contents 1 Contents Definitions 2 Important Notice 4 Chairman’s Statement 5 President’s Statement 6 Statement of the Chairman of the Board of Supervisors 7 Corporate Profile 8 Awards and Ranking 10 Summary of Accounting Data and Business Data 11 Management Discussion and Analysis 15 Changes in Share Capital and Information on Shareholders 65 Directors, Supervisors, Members of Senior Management, Employees and Branches 71 Corporate Governance 86 Report of the Board of Directors 108 Report of the Board of Supervisors 117 Important Events 124 Audit Report and Financial Report 129 Organizational Structure Chart 280 CHINA BOHAI BANK CO., LTD. Annual Report 2020 2 Denitions Definitions Articles of Association the Articles of Association of CHINA BOHAI BANK CO., LTD. Bank, our Bank, Company, CHINA BOHAI BANK CO., LTD. (渤海銀行股份有限公司), a joint stock company our Company established on December 30, 2005 in the PRC with limited liability pursuant to the relevant PRC laws and regulations, and its H Shares were listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (Stock Code: 9668) CBIRC China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (中國銀行保險監督管理委員會) CBRC the former China Banking Regulatory Commission (中國銀行業監督管理委員會) Central Bank, PBoC the People’s Bank of China China Accounting Standards Accounting Standards for -

Primary Dealers (With Effect from 1 October 2021)

HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA GOVERNMENT BOND PROGRAMME List of Primary Dealers (with effect from 1 October 2021) 1. Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited 2. Bank of Communications Company, Limited 3. BNP Paribas, Hong Kong 4. Citibank N.A. 5. Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 6. DBS Bank (Hong Kong) Limited 7. Hang Seng Bank Limited 8. Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited, The 9. Societe Generale 10. Standard Chartered Bank (Hong Kong) Limited List of Recognized Dealers (with effect from 30 September 2021) 1. ABN AMRO Bank N.V. 2. Agricultural Bank of China Limited 3. Airstar Bank Limited 4. Allied Banking Corporation (Hong Kong) Limited 5. Ant Bank (Hong Kong) Limited 6. Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited 7. Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, S.A. 8. Banco Santander, S.A. 9. Bangkok Bank Public Company Limited 10. Bank Julius Baer & Co. Ltd. 11. Bank of America, National Association 12. Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited 13. Bank of China International Limited 14. Bank of Communications Company, Limited 15. Bank of Communications (Hong Kong) Limited 16. Bank of Dongguan Co., Ltd. 17. Bank of East Asia, Limited (The) 18. Bank of India 19. Bank of Montreal 20. Bank of Nova Scotia (The) 21. Bank of Taiwan 22. Bank SinoPac, Hong Kong Branch 23. Banque Pictet & Cie SA 24. Barclays Bank plc 25. BDO Unibank, Inc. 26. BNP Paribas, Hong Kong 27. BNP Paribas Securities Services 28. Cathay Bank 29. Cathay United Bank Company, Limited 30. Chang Hwa Commercial Bank, Limited 31. -

Made in China, Financed in Hong Kong

China Perspectives 2007/2 | 2007 Hong Kong. Ten Years Later Made in China, financed in Hong Kong Anne-Laure Delatte et Maud Savary-Mornet Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1703 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1703 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 avril 2007 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Anne-Laure Delatte et Maud Savary-Mornet, « Made in China, financed in Hong Kong », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2007/2 | 2007, mis en ligne le 08 avril 2008, consulté le 28 octobre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1703 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1703 © All rights reserved Special feature s e v Made In China, Financed i a t c n i e In Hong Kong h p s c r e ANNE-LAURE DELATTE p AND MAUD SAVARY-MORNET Later, I saw the outside world, and I began to wonder how economic zones and then progressively the Pearl River it could be that the English, who were foreigners, were Delta area. In 1990, total Hong Kong investments repre - able to achieve what they had achieved over 70 or 80 sented 80% of all foreign investment in the Chinese years with the sterile rock of Hong Kong, while China had province. The Hong Kong economy experienced an accel - produced nothing to equal it in 4,000 years… We must erated transformation—instead of an Asian dragon specialis - draw inspiration from the English and transpose their ex - ing in electronics, it became a service economy (90% of ample of good government into every region of China.