Settegast Report," a Study Commissioned by H-HCEOO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Report ID

Number 21 April 2004 BAKER INSTITUTE REPORT NOTES FROM THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY BAKER INSTITUTE CELEBRATES ITS 10TH ANNIVERSARY Vice President Dick Cheney was man you only encounter a few the keynote speaker at the Baker times in life—what I call a ‘hun- See our special Institute’s 10th anniversary gala, dred-percenter’—a person of which drew nearly 800 guests to ability, judgment, and absolute gala feature with color a black-tie dinner October 17, integrity,” Cheney said in refer- 2003, that raised more than ence to Baker. photos on page 20. $3.2 million for the institute’s “This is a man who was chief programs. Cynthia Allshouse and of staff on day one of the Reagan Rice trustee J. D. Bucky Allshouse years and chief of staff 12 years ing a period of truly momentous co-chaired the anniversary cel- later on the last day of former change,” Cheney added, citing ebration. President Bush’s administra- the fall of the Soviet Union, the Cheney paid tribute to the tion,” Cheney said. “In between, Persian Gulf War, and a crisis in institute’s honorary chair, James he led the treasury department, Panama during Baker’s years at A. Baker, III, and then discussed oversaw two landslide victories in the Department of State. the war on terrorism. presidential politics, and served “There is a certain kind of as the 61st secretary of state dur- continued on page 24 NIGERIAN PRESIDENT REFLECTS ON CHALLENGES FACING HIS NATION President Olusegun Obasanjo of the Republic of Nigeria observed that Africa, as a whole, has been “unstable for too long” during a November 5, 2003, presentation at the Baker Institute. -

CITY of HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Melrose Building AGENDA ITEM: C OWNERS: Wang Investments Networks, Inc. HPO FILE NO.: 15L305 APPLICANT: Anna Mod, SWCA DATE ACCEPTED: Mar-02-2015 LOCATION: 1121 Walker Street HAHC HEARING DATE: Mar-26-2015 SITE INFORMATION Tracts 1, 2, 3A & 16, Block 94, SSBB, City of Houston, Harris County, Texas. The site includes a 21- story skyscraper. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark Designation HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY The Melrose Building is a twenty-one story office tower located at 1121 Walker Street in downtown Houston. It was designed by prolific Houston architecture firm Lloyd & Morgan in 1952. The building is Houston’s first International Style skyscraper and the first to incorporate cast concrete cantilevered sunshades shielding rows of grouped windows. The asymmetrical building is clad with buff colored brick and has a projecting, concrete sunshade that frames the window walls. The Melrose Building retains a high degree of integrity on the exterior, ground floor lobby and upper floor elevator lobbies. The Melrose Building meets Criteria 1, 4, 5, and 6 for Landmark designation of Section 33-224 of the Houston Historic Preservation Ordinance. HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE Location and Site The Melrose Building is located at 1121 Walker Street in downtown Houston. The property includes only the office tower located on the southeastern corner of Block 94. The block is bounded by Walker Street to the south, San Jacinto Street to the east, Rusk Street to the north, and Fannin Street to the west. The surrounding area is an urban commercial neighborhood with surface parking lots, skyscrapers, and multi-story parking garages typical of downtown Houston. -

Loyalty, Or Democracyat Home?

WW II: loyalty, or democracy at home? continued from page 8 claimed 275,000 copies sold each week, The "old days," when Abbott 200,000 of its National edition, 75,000 became the first black publisher to of its local edition. Mrs. Robert L. Vann establish national circulation by who said she'd rather be known as soliciting Pullman car porters and din- Robert L. Vann's widow than any other ing car waiters to get his paper out, man's wife reported that the 17 were gone. Once, people had been so various editions of the Pittsburgh V a of anxious about getting the Defender that lW5 Yt POWBCX I IT A CMCK WA KIMo) Courier had circulation 300,000. Pf.Sl5 Jm happened out ACtw mE Other women leaders of they just sent Abbott money in the mail iVl n HtZx&Vif7JWaP rjr prominent the NNPA were Miss Olive . .coins glued to cards with table numerous. syrup. Abbott just dumped all the Diggs was business manager of Anthony money and cards in a big barrel to Overton's Chicago Bee. She was elected separate the syrup and paper from the th& phone? I wbuWfi in 1942 as an executive committee cash. What Abbott sold his readers was w,S,75ods PFKvSi member, while Mrs. Vann was elected an idea catch the first train and come eastern vice president. They were the out of the South. first women to hold elected office in the n New publishers with new ideas were I NNPA. coming to the fore. W.A. -

Crawling, Standing, Walking, Carving, Building

Pioneering Your Art Career in Houston: Just Like Our Predecessors, Pursuing Fame, Fortune, Freedom, or a Place to Call Home Mayra Muller-Schmidt Sharpstown Middle School Architecture is the quintessential meter to convince each upcoming civilization on how to rate past cultures, deciding how advanced the examined society has been in this human denominator. Buildings can say a lot about their technical systems, what kind of math they employed, how fine their tools were, their artistic skills, their philosophy of life, their religion, and how far advanced their thinking skills were by how they used materials. My middle school magnet students are currently studying design and architecture as two separate courses. In architecture, they study about basic materials and touch upon design. In my design course, they get a better idea of what the ramifications are in designing any building by studying other factors. Besides reviewing the basic materials, artistic skills, and tools of the times, students get a better grasp of why a building has been manufactured a certain way. They begin to comprehend what technology, math, life conditions, and culture they are observing. In this unit, my students study an arranged collection of materials that will amplify and enhance their understanding of the culture in the selected time line. Providing the time for research study, plus having them practice reporting about the topic, prepares them in the skills of analyzing the whole. In doing this, as a regular class procedure, I will boost their observation and critical thinking as well. Their discussion skills will improve by sheer practice. -

The Pipeline

HOUSTON CHAPTER—AMERICAN GUILD OF ORGANISTS November 2015-January 2016 THE PIPELINE DEAN’S COLUMN Kathryn Sparks White echnology is changing rapidly and the AGO is working hard to keep up! Here are INSIDE THIS ISSUE T just a few of the recent advancements that benefit our image, our members, and our bottom line: Page 1 New members are being attracted by the Guild’s seven regional online-only (“virtual”) chapters Dean’s Column for organists under 30. Honorary Life Member Convention check in will be expedited: Volunteers will scan the barcode you received when you Officers registered online. We’ve developed a handy Convention app for your mobile device (more info in this issue). Page 2 And, after this season, The Pipeline will be distributed as an electronic newsletter! As they’ve always been, new and archived issues are available on our Chapter website. 2016 Houston Chapter Events The 2015-2016 Chapter Directory is now available on the chapter website. This new edition is based solely on information you provided in ONCARD. I recommend that everyone logs Page 3 onto the ONCARD website (https://www.agohq.org/oncard-login) and reviews his or her Innovation to Convention information. It is easy to log on; they have prompts to help you. In addition, please add your Leadership Award places of employment, positions, and certifications. Thanks to Andrew Bowen for his hard work in preparing the directory and monitoring ONCARD. Insert Sheet Our season began on September 20 with a brilliant and energetic concert by Patrick Scott at 2016 Convention Report St. -

Book Reviews

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 43 Issue 2 Article 12 10-2005 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation (2005) "Book Reviews," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 43 : Iss. 2 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol43/iss2/12 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HlSTORICAL ASSOCTATtON 71 BOOK REVIEWS Saving Lives, Training Caregivers. Making Discoveries: A Centennial History ofthe University i!t'Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Chester R. Burns (Texas St.ate Historical Association, The University of Texas at Austin. ] University Station D090L Austin, TX 78712-0332) 2003. Contents. Appendices. Notes. mus. Tables. Biblio. Index. P. 660. $49.95. Hardcover. Chester R. Burns, known for emphasil.ing medical ethics and bioethics in his published works, has woven the many threads of the story of the University ofTexas Medical Branch at Galveston into a beautiful tapestry thal is both unique and complete. The difficulty of the ta",k he set for himself, while totally beyond the capabilities of many historians, has been able con quered in this large volume. It is, most definitely, a "Great Man" story in that Burns concentrated on the influen,tial, moneyed people and groups who even tually made the Galveston Medical Branch a reality. -

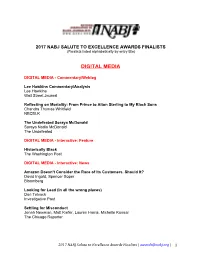

Digital Media

2017 NABJ SALUTE TO EXCELLENCE AWARDS FINALISTS (Finalists listed alphabetically by entry title) DIGITAL MEDIA DIGITAL MEDIA - Commentary/Weblog Lee Hawkins Commentary/Analysis Lee Hawkins Wall Street Journal Reflecting on Mortality: From Prince to Alton Sterling to My Black Sons Chandra Thomas Whitfield NBCBLK The Undefeated Soraya McDonald Soraya Nadia McDonald The Undefeated DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: Feature Historically Black The Washington Post DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: News Amazon Doesn’t Consider the Race of Its Customers. Should It? David Ingold, Spencer Soper Bloomberg Looking for Lead (in all the wrong places) Dan Telvock Investigative Post Settling for Misconduct Jonah Newman, Matt Kiefer, Lauren Harris, Michelle Kanaar The Chicago Reporter 2017 NABJ Salute to Excellence Awards Finalists | [email protected] | 1 DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: Feature The City: Prison's Grip on the Black Family Trymaine Lee NBC News Digital Under Our Skin Staff of The Seattle Times The Seattle Times Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement Eric Barrow New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: News Chicago's disappearing front porch Rosa Flores, Mallory Simon, Madeleine Stix CNN Machine Bias Julia Angwin, Jeff Larson, Surya Mattu, Lauren Kirchner, Terry Parris Jr. ProPublica Nuisance Abatement Sarah Ryley, Barry Paddock, Pia Dangelmayer, Christine Lee ProPublica and The New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Single Story: Feature Congo's Secret Web of Power Michael Kavanagh, Thomas Wilson, Franz Wild Bloomberg Migration and Separation: -

TEXAS NEWSPAPER COLLECTION the CENTER for AMERICAN HISTORY -A- ABILENE Abilene Daily Reporter (D) MF†*: Feb. 5, 1911; May

TEXAS NEWSPAPER COLLECTION pg. 1 THE CENTER FOR AMERICAN HISTORY rev. 4/17/2019 -A- Abilene Reporter-News (d) MF: [Apr 1952-Aug 31, 1968: incomplete (198 reels)] (Includes Abilene Morning Reporter-News, post- ABILENE 1937) OR: Dec 8, 11, 1941; Jul 19, Dec 13, 1948; Abilene Daily Reporter (d) Jul 21, 1969; Apr 19, 1981 MF†*: Feb. 5, 1911; May 20, 1913; OR Special Editions: Jun. 30, Aug. 19, 1914; Jun. 11, 1916; Sep. 24, 1950; [Jun. 21-Aug. 8, 1918: incomplete]; [vol. 12, no. 1] May 24, 1931 Apr. 8, 1956; (75th Anniversary Ed.) (Microfilm on misc. Abilene reel) [vol. 35, no. 1] (Includes Abilene Morning Reporter-News, pre- Mar. 13, 1966; (85th Anniversary Ed.) 1937, and Sunday Reporter-News - Index available) [vol. 82, no. 1] OR Special Editions: 1931; (50th Anniversary Ed.) Abilene Semi-Weekly Reporter (sw) [vol. 10, no. 1] MF†*: Jun 9, 1914; Jan 8, 1915; Apr 13, 1917 Mar. 15, 1936; (Texas Centennial Ed.) (Microfilm on Misc. Abilene reel) [vol. 1, no. 1] Dec. 6, 1936 Abilene Times (d) [vol. 1, no. 2] MF†: [Mar 5-Jun 1, 1928: incomplete] (Microfilm of Apr 1-Dec 30, 1927 on reel with West Abilene Evening Times (d) Texas Baptist) MF†: Apr 1-Oct 31, 1927 (Microfilm of Mar 5-June 1, 1928 on misc. Abilene- (Microfilm on misc. Abilene reel) Albany reel) OR: Aug 30, Oct 18, 1935 Abilene Morning News (d) OR: Feb 15, 1933 Baptist Tribune (w) MF: [Jan 8, 1903-Apr 18, 1907: incomplete (2 Abilene Morning Reporter (d) reels)] MF†*: Jul 26; Aug 1, 1918 (Microfilm on Misc. -

Houstonhouston

RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Jennifer S. Cowley Assistant Research Scientist Texas A&M University July 2001 © 2001, Real Estate Center. All rights reserved. RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Contents 2 Note Population 6 Employment 9 Job Market 10 Major Industries 11 Business Climate 13 Public Facilities 14 Transportation and Infrastructure Issues 16 Urban Growth Patterns Map 1. Growth Areas Education 18 Housing 23 Multifamily 25 Map 2. Multifamily Building Permits 26 Manufactured Housing Seniors Housing 27 Retail Market 29 Map 3. Retail Building Permits 30 Office Market Map 4. Office Building Permits 33 Industrial Market Map 5. Industrial Building Permits 35 Conclusion RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Jennifer S. Cowley Assistant Research Scientist Aldine Jersey Village US Hwy 59 US Hwy 290 Interstate 45 Sheldon US Hwy 90 Spring Valley Channelview Interstate 10 Piney Point Village Houston Galena Park Bellaire US Hwy 59 Deer Park Loop 610 Pasadena US Hwy 90 Stafford Sugar Land Beltway 8 Brookside Village Area Cities and Towns Counties Land Area of Houston MSA Baytown La Porte Chambers 5,995 square miles Bellaire Missouri City Fort Bend Conroe Pasadena Harris Population Density (2000) Liberty Deer Park Richmond 697 people per square mile Galena Park Rosenberg Montgomery Houston Stafford Waller Humble Sugar Land Katy West University Place ouston, a vibrant metropolitan City Business Journals. The city had a growing rapidly. In 2000, Houston was community, is Texas’ largest population of 44,633 in 1900, growing ranked the most popular U.S. city for Hcity. Houston was the fastest to almost two million in 2000. More employee relocations according to a growing city in the United States in the than four million people live in the study by Cendant Mobility. -

The Rice Hotel Would Be Safe

Cite Fall 1992-Winterl993 21 The Rice Hotel % MARGIE C. E L L I O T T A N D CHARLES D. M A Y N A R D , JR. i • • ia .bU I I I " f If HE* When Texas was stilt an outpost for American civilization and m Houston was a rowdy geographi- cal gamble, Jesse H. Jones' Rice Hotel came along and showed the ••»*. locals what class was all about. W DENNIS FITZGERALD, Houston Chronicle, 30 March 1975 Ladies' bridge meeting, Crystal Ballroom. Rice Hotel, shortly after opening f sentiment were all that was needed CO the hero of San Jacinto, The nonexistent From the beginning the Rice was a Houston Endowment donated the hotel to guarantee its preservation. Houston's town of Houston won out over more than landmark, one of Houston's first steel- Rice University, which had owned the Rice Hotel would be safe. But 1 5 years a dozen other contenders. The first capitol framed highnse buildings. I en thousand land upon which the building stood since without maintenance have left what was built on the site in 1837. After 1839, people turned up to tour the building on the 1900 death of William Marsh Rice. Imay be our most important landmark in when the seat of government was moved opening day. For two years the hotel continued to ruinous condition. Many Housionians, from Houston to Austin, the Allen opt ran profitably. I" 1974. howev er. the sentimentalists and pragmatists alike, brothers retained ownership of the capitol Through the years, numerous modifica- city of Houston adopted a new fire code, wonder whether their city can live up to its building, which continued to be used lor tions were made. -

PASADENA INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT Meeting of The

PASADENA INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT Meeting of the Board of Trustees Tuesday, May 27, 2008, at 5:30 P.M. AGENDA The Pasadena Independent School District Board of Trustees Personnel Committee will meet in Room L101 of the Administration Building, 1515 Cherrybrook, Pasadena, Texas on Tuesday, May 27, 2008, at 5:30 P.M. I. Convene in a Quorum and Call to Order; Invocation; Pledge of Allegiance II. Adjournment to closed session pursuant to Texas Government Code Section 551.074 for the purpose of considering the appointment, employment, evaluation, reassignment, duties, discipline or dismissal of a public officer, employee, or to hear complaints or charges against a public officer or employee. III. Reconvene in Open Session IV. Adjourn The Pasadena Independent School District Board of Trustees Policy Committee will meet in the Board Room of the Administration Building, 1515 Cherrybrook, Pasadena, Texas on Tuesday, May 27, 2008, at 5:30 P.M. I. Convene into Open Session II. Discussion regarding proposed policies III. Adjourn The Board of Trustees of the Pasadena Independent School District will meet in regular session at the conclusion of any committee meetings on Tuesday, May 27, 2008, in the Board Room of the Administration Building, 1515 Cherrybrook, Pasadena, Texas. A copy of items on the agenda is attached. I. Convene in a Quorum and Call to Order THE SUBJECTS TO BE DISCUSSED OR CONSIDERED OR UPON WHICH ANY FORMAL ACTION MIGHT BE TAKEN ARE AS FOLLOWS: II. First Order of Business Section II 1. Adjournment to closed session pursuant to -

Cite 74 29739 Final Web Friendly

TOUR COMPETITION e RDA ANNUAL ARCHITECTURE TOUR t The Splendid Houses of John F. Staub i Saturday and Sunday, March 29 and 30 1 - 6 p.m. each day. c 99K HOUSE COMPETITION . 713.348.4876 or rda.rice.edu 8 LECTURES Rice Design Alliance and AIA Houston 0 The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Brown Auditorium announce finalists. 7 p.m. G 713.348.4876 or rda.rice.edu N SANFORD KWINTER I Far From Equilibrium: Essays on Technology and Design Culture R A program by the MFA,H Bookstore Wednesday, April 2 IN FEBRUARY, FIVE FINALISTS WERE SELECTED FROM 182 and adaptability to reproduction as well as design. P GWENDOLYN WRIGHT entrants proposing a sustainable, affordable house The winner will receive an additional $5,000 New York City that addresses the needs of a low-income family in stipend. The City of Houston through the Land S Co-sponsored by RDA and Houston Mod Wednesday, April 9 the Gulf Coast region. Each will receive a $5,000 Assemblage Redevelopment Authority (LARA) R award and the competition will move forward to initiative has donated a site for the house located at THOM MAYNE, MORPHOSIS Santa Monica, CA Stage II. 4015 Jewel Street in Houston’s historic Fifth Ward, A The 2008 Sally Walsh Lecture Program a residential area northeast of Co-sponsored by RDA and AIA Houston downtown. Once constructed, Wednesday, April 16 D the winning house will be sold or auctioned to a low- BOOK SIGNING income family. N WM. T. CANNADAY Five jurors, representing The Things They’ve Done E A book about the careers of selected graduates expertise in design, sustainabili- of the Rice University School of Architecture ty, construction of affordable L Thursday, April 10 housing, and Houston’s Fifth 5-7 p.m.