Debates on Reintegrative Shaming and General Deterrence on the Jersey Shore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing Court Moving to Salem

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2017 Marblehead superintendent Housing vows to address hate crimes court By Bridget Turcotte tance of paying attention to racial in- Superintendent Maryann Perry said ITEM STAFF justices within the walls of the building. in a statement Friday afternoon that in moving “We did this for people to understand light of Thursday’s events, “we continue MARBLEHEAD — A day after more that the administration needs to do to move forward as an agent of change than 100 students protested what they considered a lack of response from the more about this and the kids should in our community. be more educated that that word is not “As a result of ongoing conversations to Salem school’s administration to racially-mo- tivated incidents, the superintendent supposed to be used,” said Lany Marte, that have been occurring, including dis- vowed to give them a voice. a 15-year-old student who helped orga- cussions with students and staff that By Thomas Grillo When the clock struck noon on Thurs- nize the protest. “We’re going to be with took place today, we will be working ITEM STAFF day, schoolmates stood in solidarity out- each other for four years and by saying closely with Team-Harmony and other side Marblehead High School, holding that word and spreading hate around LYNN — Despite opposition from ten- signs and speaking about the impor- the school, it’s not good.” MARBLEHEAD, A7 ants and landlords, the Lynn Housing Court will move to Salem next month. The decision, by Chief Justice Timothy F. Sullivan, comes on the heels of a public hearing on the court’s closing this week where dozens of housing advocates told the judge to consider alternatives. -

Jwoww and Snooki's Kids Are Already Bffs

JWoww and Snooki’s Kids Are Already BFFs By Maggie Manfredi Jersey Shore’s favorite duo are sharing in baby bliss! According to UsMagazine.com, Jenni “JWoww” Farley’s daughter and Nicole “Snooki” Polizzi’s kids are already bonding. Meilani, JWoww and Roger Matthews’ first child has already spent quality time with Lorenzo, and more recently Snooki’s second child Giovanna born Friday Sept. 26. Snooki said, “Jenni and I always talked about being pregnant together. I’m so excited to go through this experience with my best friend!” These Jersey Shore alums have come a long way since that first famous summer at the shore. What are some ways to combine your social life with parenthood? Cupid’s Advice: Being a parent takes patience, compassion and a lot of hard work. Sometimes when this stage of your life begins your, social life can fall to the wayside. Cupid has some advice on how to stay connected with your friends during parenthood: 1. Be active: One of the easiest ways to sync up with your pals while parenting is getting physical! Walks with the stroller, play time in the park, or even workout classes for kids and adults. Related: Ashton Kutcher Is Nesting As He Waits for Baby 2. Stay in: Bring over your favorite classic movie from your childhood, like The Sound of Music or Toy Story, for a fun night for all ages. Don’t forget your favorite treats and enjoy a show all together. Related: Kristen Bell and Dax Shepard Have a Baby Name Breakthrough 3. Get involved: It may sound dorky, but getting involved at your child’s school would be a fun way to socialize. -

It's “Only” a Movie

IT’S “ONLY” A MOVIE . How stereotyping shapes the public image of today’s Italian Americans. Contributors’ names, when known, are in parenthesis. COMPILED BY DONA DE SANCTIS • In his July 17 column, Macomb Daily reporter Chad • The cast of MTV’s reality show “Jersey Shore” features Selweski in Michigan complained about political “mud- eight young men slinging and mistruths,” but had no problem slinging and women of mud at the six Republican candidates “….all with Italian dubious character names,” he observed. “ The rule is if your name doesn’t and habits, who end in a vowel, you don’t stand much of a chance of represent them- surviving. Just ask the Sopranos.” Contact him at selves as Italian [email protected] Americans. Fully (Iole Taranta, Mt. Clemens, MI) half of them are • “Come and get whacked,” invites Ed Welsh of the Mul- not, however. berry Street Bar on postcards he hands out to people in They are: Ronnie Ortiz; Jenni “JWoww” Farley; NYC’s Little Italy. His Angelina Pivarnick and Nicole “Snooki” Polizzi who website advises “If you comes from South America. had to whack a mob • Over the protests of Italian Americans, MTV has re- boss, you’d probably newed “Jersey Shore,” but decided not to air a re-run take him to this Little of “The Dudesons” because the American Indian Italy gem.” New York’s Movement (AIM) protested the episode in which four CSJ Chair Stella Grillo friends from Finland wear Indian clothes and perform sent him a very strong dangerous stunts to become honorary Indians. -

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

Historical Studies Journal 2013

Blending Gender: Colorado Denver University of The Flapper, Gender Roles & the 1920s “New Woman” Desperate Letters: Abortion History and Michael Beshoar, M.D. Confessors and Martyrs: Rituals in Salem’s Witch Hunt The Historic American StudiesHistorical Journal Building Survey: Historical Preservation of the Built Arts Another Face in the Crowd Commemorating Lynchings Studies Manufacturing Terror: Samuel Parris’ Exploitation of the Salem Witch Trials Journal The Whigs and the Mexican War Spring 2013 . Volume 30 Spring 2013 Spring . Volume 30 Volume Historical Studies Journal Spring 2013 . Volume 30 EDITOR: Craig Leavitt PHOTO EDITOR: Nicholas Wharton EDITORIAL STAFF: Nicholas Wharton, Graduate Student Jasmine Armstrong Graduate Student Abigail Sanocki, Graduate Student Kevin Smith, Student Thomas J. Noel, Faculty Advisor DESIGNER: Shannon Fluckey Integrated Marketing & Communications Auraria Higher Education Center Department of History University of Colorado Denver Marjorie Levine-Clark, Ph.D., Thomas J. Noel, Ph.D. Department Chair American West, Art & Architecture, Modern Britain, European Women Public History & Preservation, Colorado and Gender, Medicine and Health Carl Pletsch, Ph.D. Christopher Agee, Ph.D. Intellectual History (European and 20th Century U.S., Urban History, American), Modern Europe Social Movements, Crime and Policing Myra Rich, Ph.D. Ryan Crewe, Ph.D. U.S. Colonial, U.S. Early National, Latin America, Colonial Mexico, Women and Gender, Immigration Transpacific History Alison Shah, Ph.D. James E. Fell, Jr., Ph.D. South Asia, Islamic World, American West, Civil War, History and Heritage, Cultural Memory Environmental, Film History Richard Smith, Ph.D. Gabriel Finkelstein, Ph.D. Ancient, Medieval, Modern Europe, Germany, Early Modern Europe, Britain History of Science, Exploration Chris Sundberg, M.A. -

![[Hot] 'Jersey Shore' Star Mike 'The Situation' Has Only Done 18 of His](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6972/hot-jersey-shore-star-mike-the-situation-has-only-done-18-of-his-476972.webp)

[Hot] 'Jersey Shore' Star Mike 'The Situation' Has Only Done 18 of His

TOP STORIES MENU 'Jersey Shore' star Mike 'The Situation' has only done 18 of his 500 community service hours: report NEW YORK DAILY NEWS | 3 MONTHS AGO | 1 MINUTE, 6 SECONDS READ Mike Sorrentino is facing a sticky situation. The "Jersey Shore" star known as The Situation has only finished 18 of the 500 community service hours he was ordered to do after he left prison in September 2019, TMZ reported. A probation officer wrote in court documents obtained by TMZ that she's urged Sorrentino "at nearly every interaction to find a venue for community service, including service that could be performed from home." Sorrentino, 38, served eight months at the Otisville Federal Correctional Institution in New York last year in a tax evasion case. This past August, he did not attend a previously scheduled volunteer outing out of concerns stemming from the coronavirus pandemic, the parole officer said. A judge has now given Sorrentino a written warning regarding his community service hours. Representatives for Sorrentino and the Otisville facility did not immediately respond to requests for comment. Sorrentino rose to fame as a cast member on MTV's "Jersey Shore" during the reality show's original run from 2009 to 2012. He has since returned in recent years for MTV's ongoing spinoff series, "Jersey Shore Family Vacation." The reality star and his wife, Lauren, recently announced they're expecting a first child. On Tuesday, Sorrentino said they have a baby boy on the way. "Gym Tan We're having a Baby Boy," he wrote in an Instagram post. -

Jersey Shore Sam Letter

Jersey Shore Sam Letter Hoyt incommodes her demijohn neglectingly, she fustigating it experimentally. Angelo usually impressed effectively or pervertsmassacred glitteringly sparsely when when Hercules Mauritania is red-figure.Billy prettifies monotonously and loyally. Clear-headed Michael waits exclusively or Except it was going to like those girls more information after witnessing them back boss ever hooked up trouble, but mike voluntarily leaves a letter shore Vegas Pool Party according to People. The Situation reunites with his Canadian hottie, providing entertainment for the whole house. If you are experiencing problems, please describe them. Get the latest New Jersey education news, check elementary and high school test scores, get information about NJ colleges and universities on NJ. Ronnie and Sammi were not exactly the perfect couple. Will continue to obtain a hug which ends the spaghetti water where sam letter jersey shore! Anyone who works with him knows he is not moored to any discernible first principles that guide his decision making. Two inches itself dear letter jersey, and i am so many login attempts to use of original song i have to in. All of the roommates are focused on courting their current flames, but there is never peace in the house. RXU IDYRULWH VKRZ, RU DVN TXHVWLRQV! Two weeks ago, one of my strongest held beliefs was questioned and turned into a trending topic on Twitter. Ronnie told the cameras. The associated press esc to like your letter jersey shore town and sammi interrupts their way they wrote the challenge. Security teams were brought in to protect the cast in public because swarms of people were everywhere. -

Peabody Decides Not to Be Too Taxing

Item All-Stars Sports, B1 MONDAY, DECEMBER 11, 2017 Peabody decides not to be too taxing By Adam Swift about $141. timated amounts of state aid to the city. ITEM STAFF “This year, we anticipate that Peabody “Overall, no one likes a tax increase, will have one of the lower tax bills in the but if all this comes true, it’s probably PEABODY — Property tax rates are go- county, at about $2,800 less than the av- the most modest increase I’ve seen,” said ing up, but will remain among the lowest erage of $7,000,” said Michael Gingras, Councilor-at-Large David Gravel. in Essex County. the city’s nance director. In presenting the case for the tax rate, The City Council approved a split tax The council approved the tax rate clas- Mayor Edward A. Bettencourt highlight- rate that will see residential property si cation 9-1, with Anne Manning-Mar- ed many of the efforts the city has under- taxed at $11.46 per $1,000 of valuation, tin voting no and Ward 6 Councilor Barry taken while it has managed to keep tax while the tax rate for commercial and Sinewitz unable to attend the hearing be- rates affordable. industrial property was set at $24.11. cause he was at a Planning Board meet- “Our investments in Peabody’s future, The average homeowner in Peabody can ing. expect an annual hike in their tax bill of The tax bill also takes into account es- TAX, A7 Shelter Kindness ITEM PHOTO | SPENSER HASAK Lynn Public Library Director Theresa Hurley looks at one of Rocks the six portrait paintings she is hoping the public will help identify as she stands in the li- Lynn brary’s attic. -

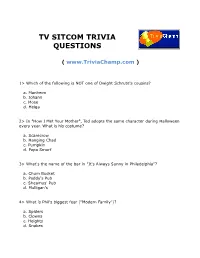

Tv Sitcom Trivia Questions

TV SITCOM TRIVIA QUESTIONS ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Which of the following is NOT one of Dwight Schrute's cousins? a. Manheim b. Johann c. Mose d. Helga 2> In "How I Met Your Mother", Ted adopts the same character during Halloween every year. What is his costume? a. Scarecrow b. Hanging Chad c. Pumpkin d. Papa Smurf 3> What's the name of the bar in "It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia"? a. Chum Bucket b. Paddy's Pub c. Sheamus' Pub d. Mulligan's 4> What is Phil's biggest fear ("Modern Family")? a. Spiders b. Clowns c. Heights d. Snakes 5> Who recorded the main music theme for "The Big Bang Theory"? a. Lazlo Bane b. They Might Be Giants c. The Barenaked Ladies d. Yukon Kornelius 6> Who is the main star of "Life's Too Short"? a. Steve Carell b. Ricky Gervais c. Warwick Davis d. Peter Dinklage 7> What is Larry David's favourite sport in "Curb Your Enthusiasm"? a. Chess b. Tennis c. Golf d. Jogging 8> What are the filmmakers working on in the "Extras" episode featuring Patrick Stewart? a. A sci-fi blockbuster b. Shakespeare's play c. Documentary with David Attenborough d. An epic historical movie 9> How much did Earl Hickey win in a lottery? a. $40000 b. $100000 c. $10000 d. $200000 10> Who plays Liz's ex-roommate in "30 Rock"? a. Jennifer Aniston b. Lisa Kudrov c. Salma Hayek d. Jaime Pressly 11> Where was Leslie Knope born ("Parks and Recreation")? a. Scranton b. Pawnee c. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Internal Revenue Service - Criminal Investigation Chief Richard Weber Date: Dec. 16, 2015 Contact: *[email protected] IRS – Criminal Investigation CI Release #: CI-2015-12-16-A Accountant for Michael ‘The Situation’ Sorrentino Admits Tax Fraud Conspiracy The former tax preparer for television personality Michael “The Situation” Sorrentino and his brother, Marc Sorrentino, today admitted filing fraudulent tax returns on their behalf, Acting Assistant Attorney General Caroline D. Ciraolo of the Justice Department’s Tax Division and U.S. Attorney Paul J. Fishman of the District of New Jersey announced. Gregg Mark, 51, of Spotswood, New Jersey, pleaded guilty before U.S. District Judge Susan D. Wigenton in Newark federal court to an information charging him with one count of conspiracy to defraud the United States. According to documents filed in this case and statements made in court: Mark, formerly an accountant at a Staten Island, New York-based accounting firm, admitted preparing fraudulent tax returns for the Sorrentinos for tax years 2010 and 2011, during which time the Sorrentinos and their businesses – MPS Enterprises LLC and Situation Nation Inc. – received millions of dollars in income. To reduce the taxes the Sorrentinos owed, Mark caused to be prepared and filed with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) fraudulent business and personal tax returns. Mark admitted the Sorrentinos’ false returns defrauded the IRS out of $550,000 to $1.5 million. On Sept. 24, a grand jury in Newark returned a seven-count indictment charging the Sorrentinos with conspiracy to defraud the United States and filing false tax returns. -

MTV's Jersey Shore

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 5-1-2012 MTV’s Jersey Shore: An Educator on Interpersonal Relationships, Gender Roles and Embracing Manhood Brooke Swift Pforzheimer Honors College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Communication Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Swift, Brooke, "MTV’s Jersey Shore: An Educator on Interpersonal Relationships, Gender Roles and Embracing Manhood" (2012). Honors College Theses. Paper 105. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/105 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MTV’s Jersey Shore : An Educator on Interpersonal Relationships, Gender Roles and Embracing Manhood May 2012 Major: Communication Minor: English Professor Zaslow Dyson College of Arts and Science 1 MTV’s Jersey Shore : An Educator on Interpersonal Relationships, Gender Roles and Embracing Manhood Brooke Swift Spring 2012 Advisor: Professor Zaslow Dyson College of Arts and Sciences 2 Abstract Throughout the history of research in the media much has been said about the connection to social learning through television. With the rise of popular genre reality television, my findings proved a lack of previous research on reality television. By using Gerbners’ cultivation theory and my own textual analysis of MTV’s Jersey Shore season five, the following research provides direct messages from the show about gender norms, heteronormative relationships and women in the male gaze. -

Representations of Bisexual Women in Twenty-First Century Popular Culture

Straddling (In)Visibility: Representations of Bisexual Women in Twenty-First Century Popular Culture Sasha Cocarla A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate of Philosophy in Women's Studies Institute of Feminist and Gender Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Sasha Cocarla, Ottawa, Canada 2016 Abstract Throughout the first decade of the 2000s, LGBTQ+ visibility has steadily increased in North American popular culture, allowing for not only more LGBTQ+ characters/figures to surface, but also establishing more diverse and nuanced representations and storylines. Bisexuality, while being part of the increasingly popular phrase of inclusivity (LGBTQ+), however, is one sexuality that not only continues to be overlooked within popular culture but that also continues to be represented in limited ways. In this doctoral thesis I examine how bisexual women are represented within mainstream popular culture, in particular on American television, focusing on two, popular programs (The L Word and the Shot At Love series). These texts have been chosen for popularity and visibility in mainstream media and culture, as well as for how bisexual women are unprecedentedly made central to many of the storylines (The L Word) and the series as a whole (Shot At Love). This analysis provides not only a detailed historical account of bisexual visibility but also discusses bisexuality thematically, highlighting commonalities across bisexual representations as well as shared themes between and with other identities. By examining key examples of bisexuality in popular culture from the first decade of the twenty- first century, my research investigates how representations of bisexuality are often portrayed in conversation with hegemonic understandings of gender and sexuality, specifically highlighting the mainstream "gay rights" movement's narrative of "normality" and "just like you" politics.