Issue 4.1 Fall 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love You 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 911 More Than A Woman 1927 Compulsory Hero 1927 If I Could 1927 That's When I Think Of You Ariana Grande Dangerous Woman "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Eat It "Weird Al" Yankovic White & Nerdy *NSYNC Bye Bye Bye *NSYNC (God Must Have Spent) A Little More Time On You *NSYNC I'll Never Stop *NSYNC It's Gonna Be Me *NSYNC No Strings Attached *NSYNC Pop *NSYNC Tearin' Up My Heart *NSYNC That's When I'll Stop Loving You *NSYNC This I Promise You *NSYNC You Drive Me Crazy *NSYNC I Want You Back *NSYNC Feat. Nelly Girlfriend £1 Fish Man One Pound Fish 101 Dalmations Cruella DeVil 10cc Donna 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc I'm Mandy 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Wall Street Shuffle 10cc Don't Turn Me Away 10cc Feel The Love 10cc Food For Thought 10cc Good Morning Judge 10cc Life Is A Minestrone 10cc One Two Five 10cc People In Love 10cc Silly Love 10cc Woman In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 2 Unlimited No Limit 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 2nd Baptist Church (Lauren James Camey) Rise Up 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

Love & Wedding

651 LOVE & WEDDING THE O’NEILL PLANNING RODGERS BROTHERS – THE MUSIC & ROMANCE A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR YOUR WEDDING 35 songs, including: All at PIANO MUSIC FOR Book/CD Pack Once You Love Her • Do YOUR WEDDING DAY Cherry Lane Music I Love You Because You’re Book/CD Pack The difference between a Beautiful? • Hello, Young Minnesota brothers Tim & good wedding and a great Lovers • If I Loved You • Ryan O’Neill have made a wedding is the music. With Isn’t It Romantic? • My Funny name for themselves playing this informative book and Valentine • My Romance • together on two pianos. accompanying CD, you can People Will Say We’re in Love They’ve sold nearly a million copies of their 16 CDs, confidently select classical music for your wedding • We Kiss in a Shadow • With a Song in My Heart • performed for President Bush and provided music ceremony regardless of your musical background. Younger Than Springtime • and more. for the NBC, ESPN and HBO networks. This superb The book includes piano solo arrangements of each ______00313089 P/V/G...............................$16.99 songbook/CD pack features their original recordings piece, as well as great tips and tricks for planning the of 16 preludes, processionals, recessionals and music for your entire wedding day. The CD includes ROMANCE: ceremony and reception songs, plus intermediate to complete performances of each piece, so even if BOLEROS advanced piano solo arrangements for each. Includes: you’re not familiar with the titles, you can recognize FAVORITOS Air on the G String • Ave Maria • Canon in D • Jesu, your favorites with just one listen! The book is 48 songs in Spanish, Joy of Man’s Desiring • Ode to Joy • The Way You divided into selections for preludes, processionals, including: Adoro • Always Look Tonight • The Wedding Song • and more, with interludes, recessionals and postludes, and contains in My Heart • Bésame bios and photos of the O’Neill Brothers. -

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Hurts 2B Human" Uscirà Il 26 Aprile Per RCA Records Ed È Disponibile Per Il Pre-Order Già Da Oggi

GIOVEDì 28 MARZO 2019 L'ottavo album di P!NK "Hurts 2b Human" uscirà il 26 aprile per RCA Records ed è disponibile per il pre-order già da oggi. Per festeggiare, la popstar pubblica anche un altro pezzo contenuto nell'album, "Hustle", P!NK, esce il 26 aprile il nuovo scritto dalla stessa P!NK insieme a Dan Reynolds degli Imagine Dragons album "Hurts 2b Human" e a Jorgen Odegard e prodotto da Odegard (con la collaborazione di Reynolds). Le 13 tracce vedono P!NK collaborare di nuovo con i suoi fidati collaboratori Max Martin, Shellback, Julia Michaels, Nate Ruess, Greg Kurstin, Billy Mann e per la prima volta con Teddy Geiger, Sasha Sloan, CRISTIAN PEDRAZZINI Beck e Sia, oltre ai featuring con Khalid, Chris Stapleton, Cash Cash e Wrabel. Il primo singolo ora in radio "Walk Me Home" ha più di 50 milioni di stream in tutto il mondo e rimane nella top 10 di iTunes US. Il video diretto da Michael Gracey (The Greatest Showman) e da Stuart Bowen, uscito settimana scorsa, ha più di 6 milioni di views. [email protected] SPETTACOLINEWS.IT La cantante americana ha da poco dato il via alla seconda tranche del suo Beautiful Trauma World Tour a partire dal 1 marzo da Sunrise, in Florida, e terminerà con ben due serate al New York City's Madison Square Garden il 21 e il 22 maggio. Per il tour sono già stati venduti più di 3 milioni di biglietti in tutto il mondo e più di 1 milione solo in America. Dal suo debutto nel 2000, P!NK (Alecia Moore) ha pubblicato 6 album ("Can't Take Me Home", "M!ssundaztood", "Try This", "I'm Not Dead", "Funhouse", "Greatest Hits So Far!!!"), venduto oltre 60 milioni di album, 75 milioni di singoli (quasi 20 milioni di brani digitali), più di 2.4 milioni di DVD in tutto il mondo e ha avuto ben 15 singoli nella top 10 della classifica Hot 100 di Billboard. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

XS Nov 2019 by ARTIST

XS Nov 2019 by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title 311 Amber Avicii Lonely Together (feat Rita 5 Seconds Of Summer Easier Ora) Teeth SOS (feat Aloe Blacc) Youngblood Without You (feat Sandro Adams, Bryan Shine A Light Cavazza) Adele Love Song Azalea, Iggy Black Widow (feat Rita Ora) Aguilera, Christina Guy What Takes His Time Fancy (feat Charli XCX) Aitch Taste (Make It Shake) B.O.B. Headband (explicit feat 2 AJR I'm Ready Chainz) Alaina, Lauren Doin' Fine B-52's, The Rock Lobster Getting Good Badu, Erykah Danger Getting Good Ballerini, Kelsea Better Luck Next Time (Instrumental) Better Luck Next Time Aldean, Jason Girl Like You (Instrumental) Rearview Town Homecoming Queen Rearview Town Homecoming Queen (Instrumental) (Instrumental) We Back I Hate Love Songs We Back (Instrumental) Miss Me More You Make It Easy Band of Heathens, The Hurricane Allen, Jimmie Best Shot Banners Got It In You Alter Bridge Watch Over You Bareilles, Sara Fire Aly & AJ Potential Breakup Song Goodbye Yellow Brick Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Road More Hearts Than Mine You Matter To Me (Instrumental) Bastille Basket Case Angels & Airwaves Kiss & Tell Joy Anne-Marie Heavy Those Nights Arthur, James Falling Like The Stars Bay, James Let It Go Naked Peer Pressures (feat Julia Say You Won't Let Go Michaels) Ashbury, Cory Reckless Love Beat, The Tears Of A Clown Reckless Love Bebe Rexha Meant To Be (feat Florida (Instrumental) Georgia Line) Au/Ra Dance In The Dark Beer, Madison All Day & All Night Ava Max Freaking Me Out Bellion, Jon All Time Low So Am I Benson, George The Greatest Love Of All Sweet But Psycho Beyonce Before I Let Go Torn Freedom Torn (Instrumental) If I Were A Boy (feat R. -

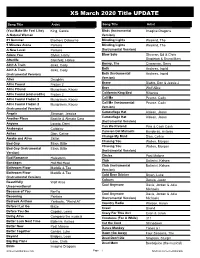

XS March 2020 Title UPDATE

XS March 2020 Title UPDATE Song Title Artist Song Title Artist (You Make Me Feel Like) King, Carole Birds (Instrumental Imagine Dragons A Natural Woman Version) 21 Summer Brothers Osbourne Blinding Lights Weeknd, The 5 Minutes Alone Pantera Blinding Lights Weeknd, The A New Level Pantera (Instrumental Version) Adore You Styles, Harry Blow Solo Sheeran, Ed & Chris Afterlife Steinfeld, Hailee Stapleton & Bruno Mars Bonny, The Ain't A Train Jinks, Cody Cinnamon, Gerry Both Ain't A Train Jinks, Cody Andress, Ingrid (Instrumental Version) Both (Instrumental Andress, Ingrid Version) Alive Daughtry Brave All is Found Frozen 2 Diablo, Don & Jessie J Bros All is FOund Musgraves, Kacey Wolf Alice California King Bed All is Found (end credits) Frozen 2 Rihanna Call Me All is Found Frozen 2 Musgraves, Kacey Pearce, Carly Call Me (Instrumental All is Found Frozen 2 Musgraves, Kacey Pearce, Carly (Instrumental Version) Version) Camouflage Hat Angels Simpson, Jessica Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Another Place Bastille & Alessia Cara Aldean, Jason (Instrumental Version) Anyone Lovato, Demi Can We Pretend Pink & Cash Cash Arabesque Coldplay Cancion Del Mariachi Banderas, Antonio Ashes Dion, Celine Change My Mind Dion, Celine Awake and Alive Skillet Chasing You Wallen, Morgan Bad Guy Eilish, Billie Chasing You Wallen, Morgan Bad Guy (Instrumental Eilish, Billie (Instrumental Version) Version) Circles Post Malone Bad Romance Halestorm Club Ballerini, Kelsea Bandages Hot Hot Heat Club (Instrumental Ballerini, Kelsea Bathroom Floor Maddie & Tae Version) Bathroom -

Time's the Revelator

Time’s the Revelator: Revival and Resurgence in Alt.country and Modern Old-Time American Music Ashley Denise Melzer A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of American Studies (Folklore). Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Dr. William Ferris Dr. Robert Cantwell Dr. Patricia Sawin © 2009 Ashley Denise Melzer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ASHLEY MELZER: Time’s the Revelator: Revival and Resurgence in Alt.country and Modern Old-Time American Music (Under the directions of Dr. William Ferris, Dr. Robert Cantwell, and Dr. Patricia Sawin) This thesis investigates the relationship between the modern old-time and alt.country movements through the comparison of four different female musicians: Abigail Washburn, Rayna Gellert, Gillian Welch, and Neko Case. These four women often pull from the same wellspring of old-time songs/structures/sounds, but their instincts come from exceptionally different places. The disparity between the ways they approach their music, reveals how the push toward modern capitalist industrialism has affected how different artists and communities access and transmit those old-world icons and sounds. Furthermore, their engagement specifically with the topic of gender exposes key tactical differences. Old-time musicians, Washburn and Gellert, work within the strictures of tradition so as to remain in dialogue with their community. Welch and Case play into the experimental bent of alt.country to emotionally affect listeners in order to create discreet, personal connections between themselves and their audience. iii To the ones who listen and love me anyway iv PREFACE In the summer, Florida is so hot the home becomes some dark prison of necessary air conditioning. -

Little Love Stories

Little Love Stories Memento Dinner for some guests on the by Ann Baker Boardwalk, not the dining room. Downtown, in the city of Rochester, The student, enjoying a second summer New York, there’s a bridge with a working at the shore, view of the Genesee River. It is Clad in white clam diggers, with named after former Rochester sunkissed bare feet, residents, Frederick Douglass and approached the young man sitting alone. Susan B. Anthony. We call it the After work, they departed together, Freddy Sue Bridge. I miss it. Briefly visited a crowded bar, Twin Lights, high above the sea, quiet, _____ dark . just the place to talk for hours. They talked every day Chance or fate? til Labor Day, when she left, for her by Judy Toohey senior year. They pledged to continue that My husband could have married my conversation . It lasted for the next 56 sister. Was it chance or fate that he years! didn’t? _____ The second weekend of our freshman year, 1953, two Harvard boys drove Love me, love my St. Bernard over from Cambridge looking to by Gini Smith meet some coeds. The two boys chose to talk with my identical twin Come meet my pooch. and me. As one chatted with my His name is Mooch. sister, the other really didn’t have a He likes a single square of steak choice. He got me! With a double spot of hootch. And that was the beginning. Was it Beware! He'll lick your shiny boot. chance? I was meeting my future And lap your hand, a swarmy smooch. -

Class Act Live Songlist

CLASS ACT LIVE SONGLIST (Everything I Do) I Do It For You – Bryan Adams (I’m Gonna Be) 500 Miles – The Proclaimers (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman – Aretha Franklin 2011 Megamix – Various Artists o Poker Face – Lady Gaga o Forget You – CeeLo Green o Party Rock Anthem – LMFAO o We Found Love – Calvin Harris f/Rihanna o Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 f/Christina Aguilera #41 – Dave Matthews Band 867-5309 (Jenny) – Tommy Tutone 90’s Rap Medley – Various Artists o Can’t Touch This – MC Hammer o Ice Ice Baby – Vanilla Ice o Good Vibrations – Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch o Regulate – Warren G o Around The Way Girl – LL Cool J o The Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air – DJ Jazzy Jeff and The Fresh Prince o Jump Around – House of Pain 99 Red Balloons – Nena A Fifth Of Beethoven – Saturday Night Fever ABC/I Want You Back – Jackson 5 Africa – Toto Ain’t It Fun – Paramore Ain’t No Mountain High Enough – Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain’t Too Proud To Beg – The Temptations All For You – Sister Hazel All Of Me – John Legend All You Need Is Love – The Beatles American Pie – Don McLean And We Danced/Day By Day – The Hooters Are You Gonna Go My Way – Lenny Kravitz At Last – Etta James Baby One More Time – Britney Spears Barbara Ann – The Beach Boys Beautiful – Carole King Because You Loved Me – Celine Dion Best Day – Taylor Swift Better Together – Jack Johnson Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Black Velvet – Alannah Myles Boogie Shoes – KC and the Sunshine Band Born To Run – Bruce Springsteen CLASS ACT LIVE SONGLIST Break My Stride – Matthew Wilder Breakfast At Tiffany’s – Deep Blue Something Brick House – The Commodores Bright – Echosmith Brokenhearted – Karmin Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Build Me Up Buttercup – The Foundations Cake By The Ocean – DNCE California Gurls/California Love – Katy Perry/Tupac/Dr.