Telling Pacific Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maiana Social and Economic Report 2008

M AIANA ISLAND 2008 SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE PRODUCED BY THE MINISTRY OF INTERNAL AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS, WITH FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE UNITED NATION DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM, AND TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE FROM THE SECRETARIAT OF THE PACIFIC COMMUNITY. Strengthening Decentralized Governance in Kiribati Project P.O. Box 75, Bairiki, Tarawa, Republic of Kiribati Telephone (686) 22741 or 22040, Fax: (686) 21133 MAIANA ANTHEM MAIANA I TANGIRIKO MAIANA I LOVE YOU Maiana I tangiriko - 2 - FOREWORD by the Honourable Amberoti Nikora, Minister of Internal and Social Affairs, July, 2007 I am honored to have this opportunity to introduce this revised and updated socio-economic profile for Maiana island. The completion of this profile is the culmination of months of hard-work and collaborative effort of many people, Government agencies and development partners particularly those who have provided direct financial and technical assistance towards this important exercise. The socio-economic profiles contain specific data and information about individual islands that are not only interesting to read, but more importantly, useful for education, planning and decision making. The profile is meant to be used as a reference material for leaders both at the island and national level, to enable them to make informed decisions that are founded on accurate and easily accessible statistics. With our limited natural and financial resources it is very important that our leaders are in a position to make wise decisions regarding the use of these limited resources, so that they are targeted at the most urgent needs and produce maximum impact. In addition, this profile will act as reference material that could be used for educational purposes, at the secondary and tertiary levels. -

Report on Second Visit to Wallis and Futuna, 4 November 1983 to 22

SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION UNPUBLISHED REPORT No. 10 REPORT ON SECOND VISIT TO KIRIBATI 1 April – 5 September 1984 and 31 October – 19 December 1984 by P. Taumaia Masterfisherman and P. Cusack Fisheries Development Officer South Pacific Commission Noumea, New Caledonia 1997 ii The South Pacific Commission authorises the reproduction of this material, whole or in part, in any form provided appropriate acknowledgement is given This unpublished report forms part of a series compiled by the Capture Section of the South Pacific Commission's Coastal Fisheries Programme. These reports have been produced as a record of individual project activities and country assignments, from materials held within the Section, with the aim of making this valuable information readily accessible. Each report in this series has been compiled within the Capture Section to a technical standard acceptable for release into the public arena. However, they have not been through the full South Pacific Commission editorial process. South Pacific Commission BP D5 98848 Noumea Cedex New Caledonia Tel.: (687) 26 20 00 Fax: (687) 26 38 18 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.spc.org.nc/ Prepared at South Pacific Commission headquarters, Noumea, New Caledonia, 1997 iii SUMMARY The South Pacific Commission's Deep Sea Fisheries Development Project (DSFDP) visited the Republic of Kiribati for the second time between April and December 1984. The visit was conducted in two distinct phases; from 1 April to 5 September the Project was based at Tanaea on Tarawa in the Gilbert Group and operated there and at the islands of Abaiang, Abemama, Arorae and Tamana. -

Kiribati Fourth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity

KIRIBATI FOURTH NATIONAL REPORT TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Aranuka Island (Gilbert Group) Picture by: Raitiata Cati Prepared by: Environment and Conservation Division - MELAD 20 th September 2010 1 Contents Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: OVERVIEW OF BIODIVERSITY, STATUS, TRENDS AND THREATS .................................................... 8 1.1 Geography and geological setting of Kiribati ......................................................................................... 8 1.2 Climate ................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Status of Biodiversity ........................................................................................................................... 10 1.3.1 Soil ................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.3.2 Water Resources .......................................................................................................................... -

The Partition of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands W

Island Studies Journal , Vol. 7, No.1, 2012, pp. 135-146 REVIEW ESSAY The Partition of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands W. David McIntyre Macmillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies Christchurch, New Zealand [email protected] ABSTRACT : This paper reviews the separation of the Ellice Islands from the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, in the central Pacific, in 1975: one of the few agreed boundary changes that were made during decolonization. Under the name Tuvalu, the Ellice Group became the world’s fourth smallest state and gained independence in 1978. The Gilbert Islands, (including the Phoenix and Line Islands), became the Republic of Kiribati in 1979. A survey of the tortuous creation of the colony is followed by an analysis of the geographic, ethnic, language, religious, economic, and administrative differences between the groups. When, belatedly, the British began creating representative institutions, the largely Polynesian, Protestant, Ellice people realized they were doomed to permanent minority status while combined with the Micronesian, half-Catholic, Gilbertese. To protect their identity they demanded separation, and the British accepted this after a UN-observed referendum. Keywords: Foreign and Commonwealth Office; Gilbert and Ellis islands; independence; Kiribati; Tuvalu © 2012 Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Context The age of imperialism saw most of the world divided up by colonial powers that drew arbitrary lines on maps to designate their properties. The age of decolonization involved the assumption of sovereign independence by these, often artificial, creations. Tuvalu, in the central Pacific, lying roughly half-way between Australia and Hawaii, is a rare exception. -

Economic and Financial Analysis

Outer Islands Transport Infrastructure Investment Project (RRP KIR 53043) ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS A. General 1. The proposed project will finance several activities to improve the safety of interisland navigation and provide resilient outer island access infrastructure for four outer islands in Kiribati. The project scope includes a hydrographic survey to establish digital chart coverage of the outer islands to make navigation safer in the country’s waters in accordance with international conventions and small-scale maritime interventions, which are needed to improve the delivery of basic goods and services to the outer islands. The project will finance rehabilitation of causeways in these islands to reduce transport costs within the islands and improve resilience to climate change and disaster risks. 2. The four islands considered for the project investment are Abaiang, Nonouti, Beru, and Tabiteuea South. Kiribati’s 33 islands are scattered over a large area of central and western Pacific Ocean and constrained by geographic isolation, a small population, and high transport and shipping costs. The nation depends on maritime transport to import essential manufactured goods, export agriculture and fishery products, and connect and resupply outer island communities. Only two ports are capable of handling international shipping—one in Betio and the other in Kiritimati and the outer islands, which are served by domestic (interisland) shipping. Safe navigation aids are limited and defined island access infrastructure nonexistent. The proposed project will tackle these constraints and ease safer access to the outer islands. 3. Standard demand analysis to calculate the project benefits is not applicable for some project components. Therefore, cost-effectiveness analysis or cost–benefit analysis was used for individual subprojects, depending on whether the benefits of the subproject were quantifiable or not.1 For example, the installation of aid to navigation (ATON) is essential but does not lead to direct economic benefit or reduced operating costs. -

Kiribati Voluntary National Review and Kiribati Development Plan Mid-Term Review New-York, July 2018

Kiribati Voluntary National Review and Kiribati Development Plan Mid-Term Review New-York, July 2018 Acknowledgments The Kiribati Voluntary National Review and Kiribati Development Plan Mid-Term Review was authored by the Government of Kiribati, as coordinated by the Director of the National Economic and Planning Office in the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. This document would not have been possible without the support of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for the Asia Pacific (UNESCAP), the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS), and the Secretariat for the Pacific Community (SPC) who offered both financial and technical support. Forward I am honoured to present this first Kiribati Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Voluntary National Review Report (VNR) and Kiribati Development Plan Mid-Term Review. The VNR has provided us with an opportunity to take stock of our current stage of development and assess where our future plans will take us. It is a chance for us to engage all the people of Kiribati in helping to shape our development story to the world. It is for this reason that we have made extensive efforts to engage with our community and service organisations, the private sector, religious bodies, development partners, and all levels of government. This report is truly a product of collaboration and partnership. Effective implementation through partnership is respected by Government. Government engages NGOs, CBOs, and the private sector in many of our national committees and taskforces to build ownership and dialogue with the community. International and regional partnerships are equally important, with Kiribati committed to a number of regional and international conventions such as the Istanbul Plan of Action, the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) Accelerated Modalities of Action (SAMOA) Pathway, the Framework for Pacific Regionalism, and the UN’s Human Rights-based conventions such as CEDAW, the Pacific Gender Equality Declaration and more. -

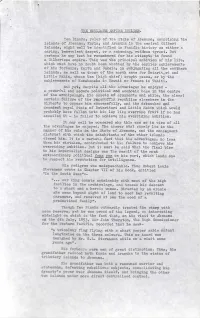

^ Distrust with Which the Inhabitants of the Other Islands 7"* Viewed Him

THE WOULi>-BE El-IPIRE BUILDER-. Tem Binoka, ruler of the State of Ahemama, comprising the isla-nds of Ahemama, Kuria, and Aranuka in the central Gilbert Islands, might well he identified in Pacific history as either a caring, benevolent despot, or a scheming, rutliless tyrant. But perhaps he may best be remembered for his attempts to found a Gilbertese empire. This was the principal ambition of his life, , which must have no doubt been vjhetted by the earlier achievements -•<7 '• oi* liis forbears, Kaitu and Uakeia, in subjugating all the southern islands, as well as those of the north save for Butaritj^ri and Little Makin, whose Uea (high chief) sought peace, or by the achievements of Kamehameha ir Hawaii or Poraare in Tahiti. And yet, despite all the advantages he enjoyed - a powerful and secure political and economic base in the centre of the archipelago, his assets of armaments and ships, the almost certain failure of the ragamuffin republics elsevjhere in the Gilberts to oppose him successfully, and the d.ebauched g^nd decadent royal State of Butaritari and Little Makin vjhich would probably have fallen into his la.p like overripe fruit if he had assailed it - he failed to achieve his overriding ambition. : It may well be v/ondered why this was so in view of all ! , ,i-7 the advantages he enjoyed. The answer must surely lie in the i manner of his rule in the State of Ahemama, and the consequent ^ distrust with which the inhabitants of the other islands 7"* viewed him. It is a curious fact that his advantages, no less then his mistakes, contributed to his failure to achieve his r • • overriding ambition. -

Nonouti Island 2007

NONOUTI ISLAND 2007 SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE PRODUCED BY THE MINISTRY OF INTERNAL AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS, WITH FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE UNITED NATION DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM AND KIRIBATI ADAPTATION PROJECT AND, TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE FROM THE SECRETARIAT OF THE PACIFIC COMMUNITY. Strengthening Decentralized Governance in Kiribati Project P.O. Box 75, Bairiki, Tarawa, Republic of Kiribati Telephone (686) 22741 or 22040, Fax: (686) 21133 NONOUTI ANTHEM E a tia Te Waa Canoe completed E a tia te Waa The Canoe is completed E a bobonga raoi In all ways required A matoa nako bwaina ngkai All materials well fixed and tightened Bwa a nang ka ieie ni biribiri Ready to sail and to run Inanon te nama i- Nonouti In the lagoon of Nonouti Tara aron butina ngkai See how it sails Tara aron birina ngkai See how it runs Tatanako iaon naona te naomoro Parting the waves rough as they are Ao ko a kan aki oaa mwina You will not be able to catch up with it Tina teirake ngaira i-Nonouti We will stand up all of us I-Nonouti Ma ni kanenei n tokaria And come in flocks to board the canoe Tina noria bwa butira ngkai To witness its swiftness E kare matoa angina As it flies with the firm wind - 2 - FOREWORD by the Honorable Amberoti Nikora, Minister of Internal and Social Affairs, July, 2007 I am honored to have this opportunity to introduce this revised and updated socio-economic profile for Nonouti island. The completion of this profile is the culmination of months of hard-work and collaborative effort of many people, Government agencies and development partners particularly those who have provided direct financial and technical assistance towards this important exercise. -

2002 04 Small Is Viable.Pdf

The U.S. Congress established the East-West Center in 1960 to foster mutual understanding and coopera- tion among the governments and peoples of the Asia Pacific region including the United States. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. govern- ment with additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, corporations, and Asian and Pacific governments. East-West Center Working Papers are circulated for comment and to inform interested colleagues about work in progress at the Center. For more information about the Center or to order publications, contact: Publication Sales Office East-West Center 1601 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawaii 96848-1601 Telephone: 808-944-7145 Facsimile: 808-944-7376 Email: [email protected] Website: www.EastWestCenter.org EAST-WEST CENTER WORKING PAPERSPAPERSEAST-WEST Pacific Islands Development SeriesSeriesPacific No. 15, April 2002 Small is Viable: The Global Ebbs and Flows of a Pacific Atoll Nation Gerard A. Finin Gerard A. Finin is a Senior Fellow in the Pacific Islands Development Program, East-West Center. He can be reached at telephone: 808-944-7751 or email: [email protected]. East-West Center Working Papers: Pacific Islands Development Series is an unreviewed and unedited prepublication series reporting on research in progress. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Center. Please direct orders and requests to the East-West Center's Publication Sales Office. The price for Working Papers is $3.00 each plus postage. For surface mail, add $3.00 for the first title plus $0.75 for each additional title or copy sent in the same shipment. -

Sustainable Development for Tuvalu: a Reality Or an Illusion?

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT FOR TUVALU: A REALITY OR AN ILLUSION? bY Petely Nivatui BA (University of the South Pacific) Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Environmental Studies (Coursework) Centre for Environmental Studies University of Tasmania Hobart, Tasmania, Australia December 1991 DECLARATION This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except when due reference is made in this thesis. Petely Nivatui ABSTRACT For development to be sustainable for Tuvalu it needs to be development which specifically sustains the needs of Tuvaluans economically, politically, ecologically and culturally without jeopardising and destroying the resources for future generations. Development needs to be of the kind which empowers Tuvaluans, gives security, self-reliance, self-esteem and respect. This is different from western perspectives which concentrate and involve a western style economy and money system in which money is the centre of everything. For Tuvaluans the economy is based on and dependent on land, coconut trees, pulaka (Cyrtosperma) and fish, as well as the exchange of these commodities. The aim of this thesis is to compare western and Tuvaluan concepts and practices of sustainable development in order to evaluate future possibilities of sustainable practices for Tuvalu. An atoll state like Tuvalu has many problems. The atolls are small, isolated, and poor in natural resources. Transport and communication are difficult and the environment is sensitive. Tuvalu is classified by the United Nations as one of the least developed countries, one dependent on foreign assistance. -

Kiribati Social and Economic Report 2008

Pacific Studies Series Studies Pacific Pacific Studies Series Kiribati Social and Economic Report 2008 After two impressively peaceful decades, there are signs of a dangerous degree of complacency in Kiribati’s view of its domestic and external affairs. Forms of cultural and political resistance to change have thus been encouraged, and these are handicapping the nation’s response to development risks. Eight leading sources of development risk confronting Kiribati are identified, and these require understanding and appropriate responses in the form of well-formulated national development strategies. Based on a thorough assessment of risks, priorities, and options by sector in the main report, 16 policy actions are recommended as keys to the full range of responses that need to be formulated to cope with development risk. About the Asian Development Bank 2008 Report KiribatiEconomic and Social ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries substantially reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two thirds of the world’s poor: 1.8 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 903 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Kiribati Social and Economic Report 2008 MANAGING DEVELOPMENT RISK Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org ISBN 978-971-561-777-2 Publication Stock No. -

Telling Pacific Lives

TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS Brij V. Lal & Vicki Luker Editors Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/tpl_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Telling Pacific lives : prisms of process / editors, Vicki Luker ; Brij V. Lal. ISBN: 9781921313813 (pbk.) 9781921313820 (pdf) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Islands of the Pacific--Biography. Islands of the Pacific--Anecdotes. Islands of the Pacific--Civilization. Islands of the Pacific--Social life and customs. Other Authors/Contributors: Luker, Vicki. Lal, Brij. Dewey Number: 990.0099 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: Choris, Louis, 1795-1828. Iles Radak [picture] [Paris : s.n., [1827] 1 print : lithograph, hand col.; 20.5 x 26 cm. nla.pic-an10412525 National Library of Australia Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Table of Contents Preface vii 1. Telling Pacic Lives: From Archetype to Icon, Niel Gunson 1 2. The Kila Wari Stories: Framing a Life and Preserving a Cosmology, Deborah Van Heekeren 15 3. From ‘My Story’ to ‘The Story of Myself’—Colonial Transformations of Personal Narratives among the Motu-Koita of Papua New Guinea, Michael Goddard 35 4. Mobility, Modernisation and Agency: The Life Story of John Kikang from Papua New Guinea, Wolfgang Kempf 51 5.