MY MOTHER's MISSING BEES Thesis Submitted to the College Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sports Drinks: the Myths Busted August 5, 2012

Sports drinks: the myths busted August 5, 2012 The Coca-Cola and McDonald's sponsorships for the London Olympics are creating outcry from health advocates, but there's one sponsorship they may be overlooking: Powerade. Powerade, the official drink for athletes at the 2012 Olympic Games (as well as the EUFA 2012), is the sister drink of the other official Olympic drink: Coca-Cola. Is it that surprising? The most common beliefs about sports drinks are that they rehydrate athletes, that all athletes (Olympic or not) can benefit from sports drinks, and that all sports drinks are created equal. Right? Wrong. Reaching for a neon-green Gatorade after your oh-so-grueling spin class may seem like a good idea, but the truth might surprise you. Sports drinks contain electrolytes (mostly potassium and sodium) and sugars to replenish what the body has lost through sweating that water alone can’t replace. The purpose of these beverages is to bring the levels of minerals in your blood closer to their normal levels, so you can continue your workout as if you just started. Sounds great, right? But don’t go reaching for the nearest bottle just yet. Not all sports drinks are created equal, and not every sports drink works the same for every athlete. Most nutritionists agree that sports drinks only become beneficial once your workout extends past 60 minutes. For Olympians, sports drinks might actually do the trick; one study from the University of Bath found that sipping on a carbohydrate-based drink helped athletes’ performances. But that doesn’t mean that drinking water ceases to be essential. -

Mexico Is the Number One Consumer of Coca-Cola in the World, with an Average of 225 Litres Per Person

Arca. Mexico is the number one Company. consumer of Coca-Cola in the On the whole, the CSD industry in world, with an average of 225 litres Mexico has recently become aware per person; a disproportionate of a consolidation process destined number which has surpassed the not to end, characterised by inventors. The consumption in the mergers and acquisitions amongst USA is “only” 200 litres per person. the main bottlers. The producers WATER & CSD This fizzy drink is considered an have widened their product Embotelladoras Arca essential part of the Mexican portfolio by also offering isotonic Coca-Cola Group people’s diet and can be found even drinks, mineral water, juice-based Monterrey, Mexico where there is no drinking water. drinks and products deriving from >> 4 shrinkwrappers Such trend on the Mexican market milk. Coca Cola Femsa, one of the SMI LSK 35 F is also evident in economical terms main subsidiaries of The Coca-Cola >> conveyor belts as it represents about 11% of Company in the world, operates in the global sales of The Coca Cola this context, as well as important 4 installation. local bottlers such as ARCA, CIMSA, BEPENSA and TIJUANA. The Coca-Cola Company These businesses, in addition to distributes 4 out of the the products from Atlanta, also 5 top beverage brands in produce their own label beverages. the world: Coca-Cola, Diet SMI has, to date, supplied the Coke, Sprite and Fanta. Coca Cola Group with about 300 During 2007, the company secondary packaging machines, a worked with over 400 brands and over 2,600 different third of which is installed in the beverages. -

The Coca-Cola Company and Monster Beverage Corporation Close on Previously Announced Strategic Partnership

June 12, 2015 The Coca-Cola Company and Monster Beverage Corporation Close on Previously Announced Strategic Partnership ATLANTA & CORONA, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- The Coca-Cola Company (NYSE: KO) and Monster Beverage Corporation (NASDAQ: MNST) announced today the closing of the previously announced strategic partnership related to an equity investment, business transfers and expanded distribution in the global energy drink category. As a result of the transaction, The Coca-Cola Company now owns an approximate 16.7% stake in Monster. The Coca-Cola Company transferred ownership of its worldwide energy business, including NOS, Full Throttle, Burn, Mother, BU, Gladiator, Samurai, Nalu, BPM, Play and Power Play, Ultra and Relentless, to Monster, and Monster transferred its non-energy business, including Hansen’s Natural Sodas, Peace Tea, Hubert’s Lemonade and Hansen’s Juice Products, to The Coca-Cola Company. Since the transaction was announced, Monster and The Coca-Cola Company and its bottlers have amended their distribution arrangements in the U.S. and Canada by expanding into additional territories and entering into long-term agreements. The Coca-Cola Company also has become Monster’s preferred global distribution partner with new international distribution commitments already in place with bottlers in Germany and Norway. In connection with the closing, The Coca-Cola Company made a net cash payment of approximately $2.15 billion to Monster. About The Coca-Cola Company The Coca-Cola Company (NYSE: KO) is the world’s largest beverage company, refreshing consumers with more than 500 sparkling and still brands. Led by Coca-Cola, one of the world’s most valuable and recognizable brands, our Company’s portfolio features 20 billion- dollar brands including, Diet Coke, Fanta, Sprite, Coca-Cola Zero, vitaminwater, POWERADE, Minute Maid, Simply, Georgia, Dasani, FUZE TEA and Del Valle. -

Coca-Cola Invites Consumers to Get “On the Go with D.O.”

June 19, 2012 Coca-Cola Invites Consumers to Get “On the Go with D.O.” Coca-Cola Partners with Track Star and Olympian David Oliver for Consumer Promotion to Benefit a Local School and Inspire Summer Physical Activity ORLANDO, Fla.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Moms will be inspired to take their families “on the go with D.O.” this summer thanks to a new consumer promotion from Coca-Cola. Coca-Cola kicks off Coca-Cola and Olympic medalist David Oliver team up for "On the Go with “On the Go with D.O." to inspire moms and their children to increase daily physical activity by offering a school "field day" with the track star. (Photo: Business Wire) D.O.,” a My Coke Rewards promotion offering a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for moms to bring 2008 Olympic bronze medalist and 2012 Olympic hopeful David Oliver (also known as “D.O.”) to their children’s school for an exciting “field day” of athletic activities. In the true spirit of the Olympics, “On the Go with D.O.” is designed to inspire African Americans to get physically active with their families and rally the community together to cheer on Oliver in his quest to compete in London for the gold. “As a long-standing sponsor of the Olympic Games, we are excited to bring an Olympian to spend time with a lucky group of children,” said Kimberly Paige, assistant vice president, African American Marketing, Coca-Cola North America. “Providing this unique opportunity is our way of sharing a creative outlet for youth to join in the fun of the Olympics and be physically active.” To participate in the promotion, consumers are encouraged to purchase Coca-Cola and donate points under-the-cap or on the package to their children’s school on MyCokeRewards.com/FieldDay now through August 12. -

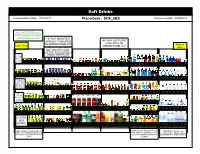

Soft Drinks Implementation Date: 17/07/2017 Planocode: SOF 6BS Previous Update: 22/05/2017

Soft Drinks Implementation Date: 17/07/2017 PlanoCode: SOF_6BS Previous Update: 22/05/2017 2GO GUIDELINE Range compliance required, all products in planogram must be stocked. Shelf locations and number of facings may be varied to reflect your local market and equipment, but only within the existing space allocated to each supplier. 4611524 MONSTER ASSAULT AVAILABLE 4611508 L&P FLOAT TO ORDER FROM 5/07 AVAILABLE TO Rear of Cash Desk ORDER FROM 31/7 PLEASE SELL THROUGH RED BULL store ZERO 355ML FROM LOCATION. REDUCE THE FACINGS OF RED BULL 355ML. ONCE YOU HAVE SOLD LTD THROUGH THE DELETED LINE EDITION REVERT TO THE PLANOGRAM. OR ZZZ "V" 250 ML CAN LIMITED EDITION OR ZZZ "V" 500 ML CAN LIMITED EDITION OR ZZZ "V" 350 ML BOTTLE CLEARA NCE DRINKS. NEW V PRODUCT LAUNCH ON 18/7. HOMEGROWN RANGE WILL BE DISPLAY IN LIMITED EDITION SPACE. AVAILABLE TO ORDER IN JULY. REFER TO PCC9 DETAILS WILL BE SENT VIA WEEKLY WILL BE COMMUNICATED VIA SUMMARY REPORTS COMMS. COMMS Soft Drinks - 6BS Implementation Date: 17/07/2017 PlanoCode: SOF_6BS Previous Update: 22/05/2017 LOC ID DART ID UPC Name Facings 1 4606620 94123524 V BOTTLE GREEN 500ML 5 2 4607588 9415767010512 V CAN GREEN 710ML 2 2GO GUIDELINE Range compliance required, all products in planogram must be 3 4606699 94129038 V BOTTLE BLUE 350ML 3 stocked. Shelf locations and number of facings may be varied to reflect your local market and equipment, but only within the 4 4607734 94123562 V BLUE BOTTLE 500ML 2 existing space allocated to each supplier. -

Mother Muff's Drink Menu

Drink Your vegetables WHAT A PERSON SHOULD DRINK IS OUR DrinkMOTHER Your MADE BLOODY MARY’S. Our very own house juiced 8 vegetable blend. We add black pepper, celery salt, Worcestershirevegetables and a hint of Tabasco to make the perfect breakfast drink. Garnished with olive, lemon and celery stalk. Just like Mother used to make. WHAT A PERSON SHOULD DRINK IS OUR PICK YOURMOTHER RIM - Kosher MADE salt, BLOODY Old Bay MARY’S. or Mother's Spicy Salt Mix. Our very own house juiced 8 vegetable blend. We add black pepper, celery salt, Worcestershire and a hint of Tabasco to make the perfect breakfast drink. HOUSEGarnished BLOODY with olive,MARYʼS lemon and 5.50 celery stalk. BLOODYJust like Mother MAMA-SAN used to make. 5.50 House made Mary mix with vodka. House made Mary mix with vodka PICK YOURDrink RIM Your- Kosher salt, Old Bay andor Mother's wasabi. Spicy Salt Mix. Kick It Up with our own house infused Poblano Vodka. 1.00 HOUSE BLOODY MARYʼS add5.50 BLOODYHORNY MAMA-SAN MARY 5.50 5.50 House madevegetables Mary mix with vodka. HouseHouse made made Mary Marymix with mix vodka with beef broth. BLOODY MADRE 5.50 and wasabi. WHAT A PERSONKick It UpWHAT SHOULDwith our own A PERSONhouse DRINK ISSHOULD OUR MOTHER DRINK IS MADE OUR BLOODY MARY! Houseinfused made Poblano Mary Vodka. mix with Tequila. 1.00 We use our very own house juiced 8 vegetable blend!MOTHER We add black MADEpepper,add celery BLOODY salt,HORNY WorcestershireMARINER MARYMARY’S. and MARY a 5.50 hint of Tabasco 6.00 to make the perfect breakfast drink. -

Coca-Cola Australia Sugar Reduction.Pdf

June 2018 We’ve come a long way since 1937 when the first Coca-Cola production facility was set- up in Australia with just ten staff and four fleet trucks. Today, The Coca-Cola Company portfolio in Australia has grown to offer more than 180 products over 26 brands and we’re proud of our progress in innovation. Importantly, our journey to becoming a total beverage company includes supporting the World Health Organization (WHO)’s recommendation that people limit added sugars to 10 per cent of their daily energy intake. The Coca-Cola Australia and Coca-Cola Amatil portfolio We have set ourselves a clear goal for 2020 to reduce by includes Fanta, FUZE Tea, Keri Juice Blenders, Mount 10% the average amount of sugar in the portfolio we sell. Franklin Lightly Sparling, Powerade, Pump, Sprite and ZICO Coconut Water. This will involve building on our ambitious reformulation and new product innovation program, and also harnessing These and many other brands of The Coca-Cola Company our marketing capabilities to encourage more people to are manufactured and distributed right across the country choose our lower kJ and no sugar beverages. by Coca-Cola Amatil, the Australian listed bottler and manufacturer. Together as part of the ‘Coca-Cola system’, The launch of Coca-Cola No Sugar, a new and improved Coca-Cola Amatil and Coca-Cola South Pacific directly sugar-free Coca-Cola, is a key part of our strategy to help employ almost 4,000 people nationwide. Australians reduce their sugar intake. It took more than five years of development to achieve a taste as similar to Coca- Since Diet Coca-Cola was launched more than 35 Cola as possible, as we know taste is key. -

2018 Annual Report

TO OUR STOCKHOLDERS I am pleased to report that 2018 represented our 26th consecutive record year of increased gross sales. Net sales rose to $3.8 billion in 2018 from $3.4 billion in 2017. Gross sales rose to $4.4 billion in 2018 from $3.9 billion in 2017. We continue to innovate in the energy drink category and following successful launches earlier this year, we anticipate future introductions of new and exciting beverages and packaging. In particular, in March 2019, we successfully launched Reign Total Body Fuel™, our new line of performance energy drinks. In 2018 and 2019, we continued to transition a number of domestic and international geographies to the system bottlers of The Coca-Cola Company. Our Monster Energy® drinks are now sold in approximately 142 countries and territories globally and our Strategic Brands, comprised of various energy drink brands we acquired from The Coca-Cola Company in 2015, are now sold in approximately 96 countries and territories globally. One or more of our energy drinks are now distributed in approximately 155 countries and territories worldwide. Our Monster Energy® brand participates in the premium segment of the energy drink category in numerous countries as do our Strategic Brands. Our affordable energy brand, notably Predator®, participates in the affordable segment of the energy drink category internationally. Norman C. Epstein, Harold C. Taber, Jr. and Kathy N. Waller are retiring from the Board of Directors effective as of the 2019 Annual Meeting and are not standing for re-election. Mr. Epstein and Mr. Taber have both served on the Board of Directors since 1992, and Ms. -

2021-05-19 Full Throttle Complaint (02125507).DOCX

Case 3:21-cv-00081-RLY-MPB Document 1 Filed 05/19/21 Page 1 of 36 PageID #: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA EVANSVILLE DIVISION ENERGY BEVERAGES LLC, a ) Civil Action No. 3:21-cv-81 Delaware limited liability company ) ) Plaintiff, ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED ) v. ) ) FULL THROTTLE AUTOMOTIVE ) LLC, an Indiana limited liability ) company ) Defendant. COMPLAINT FOR TRADEMARK INFRINGEMENT, TRADE DRESS INFRINGEMENT, FALSE DESIGNATION OF ORIGIN, AND UNFAIR COMPETITION Plaintiff Energy Beverages LLC (“Plaintiff” or “Energy Beverages”) hereby files this complaint against Defendant Full Throttle Automotive LLC (“Defendant” or “FTA”) and alleges as follows: I PARTIES 1. Energy Beverages is a limited liability company organized under the laws of the State of Delaware. Energy Beverages has its principal place of business at 2390 Anselmo Drive, Corona, California 92879. 2. FTA is a domestic limited liability company organized under the laws of the State of Indiana. Upon information and belief, FTA maintains its principal place of business at 9515 Seib Rd., Evansville, Indiana 47725. -1- Case 3:21-cv-00081-RLY-MPB Document 1 Filed 05/19/21 Page 2 of 36 PageID #: 2 II JURISDICTION AND VENUE 3. This is an action for (1) trademark infringement, trade dress infringement, and false designation of origin under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a), (2) trademark infringement under 15 U.S.C. § 1114, (3) common law trademark infringement, and (4) unfair competition. 4. The Court has original subject matter jurisdiction over the claims that relate to trademark infringement, trade dress infringement, and false designation of origin pursuant to 28 U.S.C. -

Chronic Intake of Energy Drinks and Their Sugar Free Substitution Similarly Promotes Metabolic Syndrome

nutrients Article Chronic Intake of Energy Drinks and Their Sugar Free Substitution Similarly Promotes Metabolic Syndrome Liam T. Graneri 1,2, John C. L. Mamo 1,3, Zachary D’Alonzo 1,2, Virginie Lam 1,3 and Ryusuke Takechi 1,3,* 1 Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute, Curtin University, Perth, WA 6845, Australia; [email protected] (L.T.G.); [email protected] (J.C.L.M.); [email protected] (Z.D.); [email protected] (V.L.) 2 Curtin Medical School, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, Perth, WA 6845, Australia 3 School of Population Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, Perth, WA 6845, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-8-92662607 Abstract: Energy drinks containing significant quantities of caffeine, taurine and sugar are increas- ingly consumed, particularly by adolescents and young adults. The putative effects of chronic ingestion of either standard energy drink, MotherTM (ED), or its sugar-free formulation (sfED) on metabolic syndrome were determined in wild-type C57BL/6J mice, in comparison to a soft drink, Coca-Cola (SD), a Western-styled diet enriched in saturated fatty acids (SFA), and a combination of SFA + ED. Following 13 weeks of intervention, mice treated with ED were hyperglycaemic and hypertriglyceridaemic, indicating higher triglyceride glucose index, which was similar to the mice maintained on SD. Surprisingly, the mice maintained on sfED also showed signs of insulin resistance with hyperglycaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, and greater triglyceride glucose index, comparable to the ED group mice. In addition, the ED mice had greater adiposity primarily due to the increase in white adipose tissue, although the body weight was comparable to the control mice receiving Citation: Graneri, L.T.; Mamo, J.C.L.; D’Alonzo, Z.; Lam, V.; Takechi, R. -

SENATE BILL 110 by Tate HOUSE BILL 347 by Mcmanus an ACT to Amend Tennessee Code Annotated, Title 39; Title 40 and Title

SENATE BILL 110 By Tate HOUSE BILL 347 By McManus AN ACT to amend Tennessee Code Annotated, Title 39; Title 40 and Title 57, relative to alcoholic beverages. BE IT ENACTED BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF TENNESSEE: SECTION 1. Tennessee Code Annotated, Title 57, Chapter 4, Part 1, is amended by adding the following language as a new, appropriately designated section: (a) It is unlawful for any person to knowingly sell any energy drink at a business with a license or permit to serve or sell liquor by the drink. Any person who violates this section commits a Class A misdemeanor, punishable only by fine and suspension of the person's license or permit to serve or sell liquor by the drink for a certain time as determined appropriate by the entity that issued the license or permit. (b) For purposes of this section, "energy drink": (1) Means any beverage: (A) That contains methylxanthines; and (B) Whose main purpose, as advertised, is to boost a person's energy; and (2) Includes, but is not limited to, 180, 5-Hour Energy, AMP Energy, Bacchus-F, Battery, Battery energy shot, Bawls, Blue Charge, Blue Energy, Boo Koo, Burn, Cintron Energy Enhancer, Coca-Cola Blak, Cocaine, Crunk Energy Drink, Emerge Stimulation Drink, Enviga, Full Throttle, Go Fast, Hustler, Irn-Bru 32, Jolt Cola, King 888, Kore, Lucozade Alert, Lucozade Sport with Caffeine Boost, MAD DOG Energy Lemonade, Monster, Mother, Mountain Dew MDX, NOS, Pepsi Max, Powerking, Pure!, Red Bull, Red Eye, Red Rooster, Red Thunder, Redline, Relentless, RELOAD, Rip It, Rockstar energy drink original, HB0347 001452 -1- Semtex, Shark Stimulation, SoBe Adrenaline Rush, Sparks, Spike Shooter, Tab Energy, Urge Intense, Vault, Glaceau VitaminEnergy, Wired Energy Drink, Wired Sugar Free, XS Energy Drink, and Zipfizz. -

Beverage REPORT Part 2

beverage REPORT part 2 Retailers seek merchandising strategies for hopped-up energy category By Jerry Soverinsky t’s just past midnight on an unsea- young clerk, noticing the three energy takes a swig and heads back out into sonably warm December Chicago drinks that the man has placed on his the night. night. The hip Lakeview neighbor- counter. It’s a repeated theme, but not just hood, just blocks from Wrigley “Busy night,”the driver replies as he with taxi drivers. With bar patrons. IField,is alive with activity.I wander finishes his purchase, opens a drink, Couples returning from dates. Stu- into a convenience store, pay for a dents. They’re buying energy large coffee and grab a stool by the drinks. Maybe not as much as window to watch a kaleidoscope of THE they’re buying soda, beef jerky and activity unfold before my eyes. To BOTTOM LINE M&M’s, but enough so that I self- appreciate Chicago’sdiversity,there’s Energy-drink sales have spiked over the past consciously look at my black, no better perch. five years, prompting a recent Packaged Facts decaffeinated coffee and suddenly Several taxis are in line outside to report to predict the beverage segment will feel old and out of touch (kind of access the gasoline pumps. Business continue to grow annually at 12% with total like when my niece mentions Face- isheavy tonight,andthebanterinside sales, topping $9 billion by 2011—a whopping book or Mischa Barton). the store remains loud and constant. 650% increase from the category’s $1.2 billion “On a busy night, a Saturday A 30-something man files out of in sales in 2002.