Larger Participant Rulemaking 76 Fed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thank You! Match Your Gift to GSCM Here’S How

Thank You! Match Your Gift to GSCM Here’s how: Look for your employer in the sample list below. Don’t see them? Ask your HR department if your company matches 1 your gift or donates to your volunteer hours. 2 Follow the necessary steps with your HR department. Let us know if your company will be matching your gift by 3 calling 410.358.9711, Ext. 244 or email us at [email protected]. Here are some of the companies that match gifts: A ConAgra Foods, Inc. H Connexus Energy AT&T HP, Inc. Constant Contact, Inc. AAA Harris Corp. Constellation Brands, Inc. AARP Heller Consulting, Inc. Costco AEGIS Henry Crown & Co. Craigslist, Inc. ARAMARK Henry Luce Foundation CyberGrants, Inc. ATAPCO Hewlett Packard Adobe Systems, Inc. D Highmark, Inc. Advanced Instructional Systems, Inc. Hillman Co. DEMCO, Inc. Allstate Home Depot DMB Associates, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. Honeywell International, Inc. DPL, Inc. American Express Co. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Co. DTC Global Services, LLC American Fidelity Assurance Corp. Howard S. Wright Constructors DTE Energy American Honda Motor Co., Inc. Humana, Inc. Dell, Inc. American Vanguard Corp. Deutsche Bank AG Ameriprise Financial, Inc I Dodge & Cox Aon Corp. iParadigms, LLC Dolby Laboratories, Inc. Apple ING Financial Services, LLC Dorsey & Whitney LLP Association of American Medical Colleges Ingersoll Rand Dun & Bradstreet Corp. Astoria Bank Investment Technology Group, Inc. Avon Products, Inc. E Itron, Inc. B eBay J eClinicalWorks BP Foundation J.P. Morgan Chase Eli Lilly & Co. Bank of America Corp. JC Penney’s Energen Barnes Group, Inc. Jackson Hewitt Tax Service, Inc. -

In This Month's Newsletter

Data-Based Consulting Heavy Equipment Rental In this month’s newsletter: 2 Monthly Commentary and Summary 3 Recent Industry News 6 Loan Market Update & Technical Conditions Knowledge-Based Cons. Non-Heavy Equip. Rental 8 Revolver and Term Loan Recent Issuance 11 Investment Grade Bond Market Update & Outlook 13 Investment Grade Recent Bond Issuance 14 Investment Grade Debt Comparables Advertising / Marketing Facility Services 17 High Yield Bond Market Update & Outlook 19 High Yield Recent Bond Issuance 20 High Yield Debt Comparables 22 Equity Capital Markets Update & Outlook Printing Services Auction Services 24 Equity Capital Markets Relative Valuation 25 Equity Capital Markets Recent Issuance 26 Operating Statistics Diversified / Other 29 Macroeconomic Indicators 32 Current Interest Rate Environment 33 Notable Mergers and Acquisitions Activity 36 KeyCorp & KBCM Overview & Capabilities Disclosure: KeyBanc Capital Markets is a trade name under which corporate and investment banking products and services of KeyCorp and its subsidiaries, KeyBanc Capital Markets Inc., Member NYSE/FINRA/SIPC, and KeyBank National Association (“KeyBank N.A.”), are marketed. Securities products and services are offered by KeyBanc Capital Markets Inc. and its licensed securities representatives, who may also be employees of KeyBank N.A. Banking products and services are offered by KeyBank N.A. This report was not issued by our research department. The information contained in this report has been obtained from sources deemed to be reliable but is not represented to be complete, and it should not be relied upon as such. This report does not purport to be a complete analysis of any security, issuer, or industry and is not an offer or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities. -

2020-Proxy-Statement.Pdf

April 1, 2020 Dear Fellow Stockholders: I am pleased to invite you to join our Board of Directors and senior leadership for our 2020 Annual Meeting of Stockholders (Annual Meeting), which will be held on Tuesday, May 12, 2020, at 12:00 p.m. Central Daylight Time. Our Annual Meeting will be a virtual meeting of stockholders, which will be conducted via live audio webcast. The attached Notice of Annual Meeting of Stockholders and proxy statement will serve as your guide to the business to be conducted at the meeting. We are mailing a Notice of Internet Availability of Proxy Materials (Notice) to our stockholders. We believe the Notice process allows us to provide our stockholders with the information they desire in a timely manner, while saving costs and reducing the environmental impact of our Annual Meeting. The Notice contains instructions on how to access our 2019 Annual Report (which includes our 2019 Form 10-K), proxy statement and proxy card over the Internet, as well as instructions on how to request a paper copy of the materials, if desired. Your vote is very important to us. We encourage you to sign and return your proxy card and/or vote by telephone or via the Internet following the instructions on the Notice as soon as possible, so that your shares will be represented and voted at the Annual Meeting. Instructions on how to vote are on page 11. We urge you to read the accompanying proxy statement carefully and to vote FOR the director nominees proposed by the Board of Directors and FOR the other proposals in accordance with the recommendations of the Board of Directors. -

In the United States District Court for the District of Kansas

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS AD ASTRA RECOVERY ) SERVICES, INC., ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Case No. 18-1145-JWB-ADM ) JOHN CLIFFORD HEATH, ESQ., et al., ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM AND ORDER This matter comes before the court on Plaintiff Ad Astra Recovery Services, Inc.’s (“Ad Astra”) Motion for Leave to Amend the First Amended Complaint (ECF 214) and, separately, two discovery motions that involve the same set of documents: (1) Defendants’ Motion for a Protective Order (ECF 227), and (2) Ad Astra’s Motion to Compel Defendants’ Removal of their Attorneys’ Eyes Only Designation and Redactions of Certain Agreements (ECF 231). Ad Astra initiated all of the issues raised in these motions months after the March 13 discovery deadline, in the midst of multiple rounds of revisions to the pretrial order. Ad Astra’s motion for leave to amend seeks to add a civil conspiracy claim. This motion is denied because Ad Astra has not shown good cause for filing this motion well beyond the scheduling order deadline to amend the pleadings. Ad Astra could have pleaded this claim sooner. The motion is also denied based on undue delay, futility, and undue prejudice to defendants if Ad Astra were allowed to inject this new legal theory at this late stage of the litigation. The parties’ competing motions to compel and for a protective order dispute whether defendants may maintain their Attorneys’ Eyes Only (“AEO”) designation and redaction of pricing information in defendant Lexington Law’s contracts with the three major credit bureaus. As explained below, Ad Astra’s motion to compel these contracts to be reproduced without the AEO designation and redactions is denied, and defendants’ motion for a protective order allowing them to maintain the AEO designation and redactions is granted. -

Ctpf Illinois Economic Opportunity Report

CTPF ILLINOIS ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY REPORT As Required by Public Act 096-0753 for the period ending June 30, 2021 202 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE I 1 Illinois-based Investment Manager Firms Investing on Behalf of CTPF TABLE II Illinois-based Private Equity Partnerships, Portfolio Companies, 2 Infrastructure, and Real Estate Properties in the CTPF Portfolio TABLE III 14 Illinois-based Public Equity Market Value of Shares Held in CTPF’s Portfolio TABLE IV 18 Illinois-based Fixed Income Market Value of Shares Held in CTPF’s Portfolio TABLE V Domestic Equity Brokerage Commissions Paid to Illinois-based 19 Brokers/Dealers TABLE VI 20 International Equity Brokerage Commissions Paid to Illinois-based Brokers/Dealers TABLE VII Fixed Income Volume Traded through Illinois-based Brokers/Dealers 21 (par value) 2021 CTPF ILLINOIS ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY REPORT REQUIRED BY PUBLIC ACT 096-0753 FOR THE PERIOD ENDING JUNE 30, 2021 TABLE I Illinois-based Investment Manager Firms Investing on Behalf of CTPF Table I identifies the economic opportunity investments made by CTPF with Illinois-based investment management companies. As of June 30, 2021, Total Market/Fair Value of Illinois-based investment managers was $3,121,157,662.18 (23.74%) of the total CTPF investment portfolio of $13,145,258,889.14. Market/Fair Value % of Total Fund Investment Manager Firms Location As of 6/30/2021 (reported in millions) Adams Street Chicago $ 319.69 2.43% Ariel Capital Management Chicago 83.44 0.63% Attucks Asset Management Chicago 274.06 2.08% Ativo Capital Management1 Chicago -

ATG MI ADM Security Breach

ATG MI ADM Security Breach From: Patel, Roshni <[email protected]> Sent: Tuesday, May 10, 2016 7:30 AM To: ATG MI ADM Security Breach Subject: LendUp Notice Attachments: Washington Consumer Notice DMEAST_25506243(1).PDF To Whom It May Concern: We are providing notice to the Office of the Attorney General pursuant to RCW 19.255.010 of an incident that may affect 708 Washington residents. Please find attached the written notice being sent to consumers on May 11, 2016. If you should have any difficulty opening the attachment or have any questions, please feel free to contact Kim Phan by telephone at (202) 661‐ 2286 or email at [email protected]. My contact information also appears below for your reference. Sincerely, Roshni Patel Associate Ballard Spahr LLP 1909 K Street, NW, 12th Floor Washington, DC 20006-1157 Direct: (202) 661-7686 [email protected] | www.ballardspahr.com 1 Processing Center ● P.O. BOX 141578 ● Austin, TX 78714 e"]$Tgr5^ k+ 00001 %DjoYnY:gV JOHN Q. SAMPLE aa!!!!!!a!a!a!a! 00001 1234 MAIN STREET ACD1234 ANYTOWN US 12345-6789 May 11, 2016 Dear John Sample, We are writing to notify you about an incident that may have involved some of your personal information. We have no reason to believe that any of your personal information is at risk. We understand the importance of protecting the privacy and security of your personal information, and we take our obligations seriously. We apologize for any inconvenience this incident may cause you. WHAT HAPPENED? Earlier this year during a routine examination, we discovered that personal information for a small subset of visitors to our website had been made available to third-party companies. -

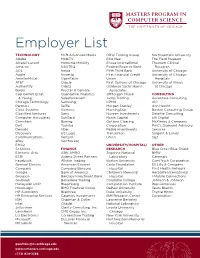

Employer List

Employer List TECHNOLOGY MLB Advanced Media DRW Trading Group Northwestern University Adobe MobiTV Ellie Mae The Field Museum Alcatel-Lucent Motorola Mobility Enova International Theorem Clinical Amazon NAVTEQ Federal Reserve Bank Research AOL Nokia Fifth Third Bank University of Chicago Apple Novetta First Financial Credit University of Chicago ArcellorMittal OpenTable Union Hospitals AT&T Oracle First Options of Chicago University of Illinois Authentify Orbitz Goldman Sachs Harris at Chicago Baidu Procter & Gamble Associates Cap Gemini Ernst Quantative Analytics JPMorgan Chase CONSULTING & Young Salesforce.com Jump Trading Accenture Consulting Chicago Technology Samsung KPMG AIC Partners Selfie Morgan Stanley Aon Hewitt Cisco Systems Siemens MorningStar Boston Consulting Group Classified Ventures Sony Nuveen Investments Deloitte Consulting Computer Associates SunGard Ronin Capital EKI Digital Comshare Boeing Options Clearing McKinsey & Company Dell Toshiba Corporation PwC’s Diamond Advisory Denodo Uber Peak6 Investments Services Discovery US Logic TransUnion Sargent & Lundy Communications Verizon USAA Sg2 eBay VertMarket EMC2 UNIVERSITY/HOSPITAL/ OTHER Solutions FINANCE RESEARCH Blue Cross-Blue Shield Eletronic Arts ABN AMRO Argonne National BMW ESRI Adams Street Partners Laboratory Caremark Facebook Allston Trading Boston University ComPsych Corporation General Electric American Express Carle Foundation Eli Lilly & Company Company Company Bancorp Hospital First Health Network Google Bank of America Children’s Memorial Herbalife International Groupon Barclays Investment Bank Hospital i-Mobile Connections GrubHub Belvedere Trading Columbia College Johnson & Johnson Honeywell UOP Bloomberg Computation Institute PepsiAmericas HookLogic BMO Financial Group DePaul University Sears Brands HP Autonomy Braintree Duke University Toyota Motor HP Enterprise Services Calamos Investments IBM Research Center Corporation IBM Chapman & Cutler Lawrence Berkeley Intel Citadel National Laboratory Jellyvision Clarity Consulting, Inc. -

1:20-Cv-03315 Document #: 1 Filed: 06/04/20 Page 1 of 40 Pageid #:1

Case: 1:20-cv-03315 Document #: 1 Filed: 06/04/20 Page 1 of 40 PageID #:1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS CITY OF BOSTON CREDIT UNION, Plaintiff, Civil Action No. v. Class Action Complaint FAIR ISAAC CORPORATION, Jury Trial Demanded Defendant. Case: 1:20-cv-03315 Document #: 1 Filed: 06/04/20 Page 2 of 40 PageID #:2 Plaintiff City of Boston Credit Union (“Plaintiff”), on behalf of itself and all others similarly situated, files this complaint against Fair Isaac Corporation (“Fair Isaac” or “Defendant”) for violations of federal antitrust laws and state antitrust and consumer protection laws. The allegations herein are based on Plaintiff’s personal knowledge as to its own acts and on information and belief as to all other matters, such information and belief having been informed by the investigation conducted by and under the supervision of its counsel. I. NATURE OF THE CASE 1. A credit score is a three-digit, statistical number designed to represent a borrower’s credit risk or the likelihood that that borrower will pay back a loan on time. Fair Isaac creates and distributes a certain brand of credit scores, known as FICO® Scores. FICO Scores have dominated the credit score market for nearly three decades. 2. Fair Isaac has been vocal about its dominant position in the market, bragging that their FICO Scores are “the 800-pound gorilla.”1 In fact, Fair Isaac advertises that its FICO Scores are used for 90% of all lending decisions in the United States and that it sells four times more FICO Scores per year than McDonald’s sells hamburgers worldwide.2 3. -

Fieldglass Secures Investment from Madison Dearborn Partners

Fieldglass Secures Investment From Madison Dearborn Partners Investment from fellow Chicago-based firm to accelerate Fieldglass' global market expansion and strategic development initiatives Chicago - January 1, 2012 Fieldglass, Inc., the leading technology provider to procure and manage contingent labor and services, today announced that it has secured a substantial investment from Madison Dearborn Partners. The transaction, which values Fieldglass in excess of $220 million, validates Fieldglass’ leadership position in the growing services procurement market. Upon completion of the investment, Madison Dearborn will hold a majority ownership position in Fieldglass. Jai Shekhawat, founder and CEO of Fieldglass, and the company’s management team will retain a significant ownership stake. Fieldglass’ Software as a Service (SaaS) Vendor Management System (VMS) enables companies to more efficiently procure and manage contingent labor and services such as statement of work engagements, offshore projects and independent contractors across dozens of categories, which is especially critical in today’s dynamic market environment. Known for its ability to support the largest and most complex contingent workforce management and services programs, Fieldglass is recognized to have the industry’s largest installed base, and is rapidly scaling its global presence. Its clients include American Airlines, CVS Caremark, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Monsanto and Verizon. Industry research provider Staffing Industry Analysts (SIA) predicts the use of VMS will grow dramatically in the next couple of years. According to SIA’s 2009 Annual Buyers’ Survey, VMS usage is expected to more than double to 81 percent in 2011, up from just 34 percent in 2007. “We selected Madison Dearborn for its technology-enabled services portfolio and business integrity, and with its backing we will have additional flexibility to make investments in strategic development initiatives and expand into new, global markets,” said Jai Shekhawat, founder and CEO, Fieldglass. -

ANA Integrated Marketing Members-Only Conference at Microsoft Advertising

ANA Integrated Marketing Members-Only Conference at Microsoft Advertising June 4, 2013 | Chicago, Ill. Join the conversation on Twitter by using #ANAmarketers Upload photos and video, and make comments on facebook.com/ANA Table of Contents ANA Integrated Marketing Members-Only Conference at Microsoft Advertising Agenda ............................................................................ pg 1 Speaker Bios .................................................................... pg 3 Attendees ........................................................................ pg 6 ANA Information .............................................................pg 10 www.ana.net Agenda ANA Integrated Marketing Members-Only Conference at Microsoft Advertising Tuesday, June 4 Breakfast (8:15 a.m.) CARS.COM “NO DRAMA” APPROACH TO MULTISCREEN MAYHEM: INTEGRATED MARKETING CREATING ENGAGING CONTENT ACROSS MULTIPLE SCREENS General Session (9:00 a.m.) Cars.com’s 2013 Super Bowl ad kicked off the organization’s first truly integrated More consumers own upwards of four COCA-COLA LETS FANS DECIDE THE marketing campaign spanning all audi- connected devices, relating with content ENDING OF THEIR BIG GAME CAMPAIGN ences: consumers, customers, the industry, in a way that was never before possible. and employees. All centered around one While marketers are poised to reap the After their award-winning Polar Bowl BIG IDEA: the campaign drives a consistent benefit of more touchpoints across screens, campaign in Super Bowl 2012, Coca-Cola message across all consumer and -

20-297 Transunion LLC V. Ramirez (06/25/2021)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus TRANSUNION LLC v. RAMIREZ CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 20–297. Argued March 30, 2021—Decided June 25, 2021 The Fair Credit Reporting Act regulates the consumer reporting agencies that compile and disseminate personal information about consumers. 15 U. S. C. §1681 et seq. The Act also creates a cause of action for con- sumers to sue and recover damages for certain violations. §1681n(a). TransUnion is a credit reporting agency that compiles personal and financial information about individual consumers to create consumer reports and then sells those reports for use by entities that request information about the creditworthiness of individual consumers. Be- ginning in 2002, TransUnion introduced an add-on product called OFAC Name Screen Alert. When a business opted into the Name Screen service, TransUnion would conduct its ordinary credit check of the consumer, and it would also use third-party software to compare the consumer’s name against a list maintained by the U. S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of terrorists, drug traffickers, and other serious criminals. -

Case 2:06-Cv-02304-JPO Document 167 Filed 10/24/07 Page 1 of 8

Case 2:06-cv-02304-JPO Document 167 Filed 10/24/07 Page 1 of 8 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS CAROL BETH TILLEY, ) ) ) Plaintiff, ) v. ) Case No. 06-2304-JAR ) EQUIFAX INFORMATION SERVICES, ) LLC, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ORDER This case comes before the court on the motion (doc. 158) of the plaintiff, Carol Beth Tilley, to compel defendant Global Payments, Inc. (“Global”) to direct division general counsel David L. Green to answer certain deposition questions he was instructed not to answer on the basis of attorney-client privilege; alternatively, plaintiff requests that Global be required to produce another witness pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 30(b)(6) to answer the questions in issue. Global has filed a response (doc. 162), and the plaintiff has replied (doc. 163). As indicated during the final pretrial conference on October 23, 2007, the court finds that Global’s attorney-client privilege objections are invalid and therefore overruled. It follows that the instant motion is granted. This case was brought by plaintiff under the Federal Fair Credit Reporting Act (“FCRA”), 15 U.S.C. § 1681, et seq., and state defamation law. Highly summarized, plaintiff alleges that Global published defamatory statements about her to other defendants who recently settled out of this case, i.e., CSC, Equifax, TransUnion, and Experian. O:\ORDERS\06-2304-158.wpd Case 2:06-cv-02304-JPO Document 167 Filed 10/24/07 Page 2 of 8 Significantly Mr. Green, as Global’s in-house counsel, was directly involved in the underlying controversy, and he communicated with plaintiff during September and October 2005.