A Place for Photography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Am a Miner

EARCH 1. Mine Try finding this artwork and fill in the missing SPOT THE DIFFERENCE! S CAN YOU READ D 2. Photograph details by looking at the LABEL. The label tells us Find the 5 ways the image on the le has been changed! R 3. Label more information about the artwork, such as the O S A M B S O U C T M 4. Museum AN ARTWORK? TITLE THE NAME of the work, the year it was W 5. Camera made and the MEDIUM (what was used to make T D G J Y A N A G I the artwork): H J M U S E U M W N Y G C U L A B E L E I was made by David Goldbla K N L B Z T R R O I P H O T O G R A P H My title is Miner, Consolidated J H B F K M E L O T Mine Reef, Roodepoort I am a ______________________ (medium) I was made in the year ______________ HELP VINCENT FIND THE GOLD! Photographs like the ones Goldbla made were taken with a film camera, and the images are stored on a roll of film rather than a memory card! Can you complete this image this complete you Can half?the second drawing by MIRROR–MIRROR E? ON MY WAY HOME DAVID GOLDBLATT: I SE O Draw some memorable things in the circles below! ON THE MINES I AM A MINER D T Write down all the things you Name Age School A The best thing I saw at My guide looked H can name in this photograph! Norval Foundation: like this: Hard hat W WHAT DO I SEE? This type of artwork is called a PHOTOGRAPH. -

Goldblatt 1830 Metres (5000 to 6000 Feet) Elevation, on Which Lies South Africa’S Largest Conurbation

ons after 1834 to escape British domination. Also the Afrikaner youth movement. Whites A collective term for light-skinned people predomi- David nantly of European stock. Witwatersrand Afrikaans Wit = white + waters = waters + rand = ridge. Geographical east-west formation at between 1500 and Goldblatt 1830 metres (5000 to 6000 feet) elevation, on which lies South Africa’s largest conurbation. See Reef. Fifty-one years Xhosas An Nguni African people who live mainly along the southeastern rain belt. Zulus An Nguni African people who live mainly in KwaZulu- 8 February - 14 April 2002 Natal. ACTIVITIES AROUND THE EXHIBITION ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION FRIDAY 8 FEBRUARY AT 7.30 PM The photographer David Goldblatt, Pepe Baeza, journalist and lecturer at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, and Alfred Bosch, professor of African History at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra, will discuss Goldblatt’s work and the South African historical and cultural context. Auditorium. Limited number of seats. For further information: Tel. 93 412 14 13 [email protected] The provincial and homeland names and borders used in this exhibition are those that applied during most of the years of Goldblatt's photography and before South Africa's transition to democratic government in 1994. © Courtesy of Edicions Bellaterra ing the National Party to power in 1948 and keeping it there Soweto From “South Western Townships”, Johannesburg’s for more than 40 years. “location”, the extensive series of townships in which African 2 pass laws Laws controlling the movements and residential rights residents of Johannesburg were required to live in terms of seg- of Africans, principally by means of a “pass” or pass book, signed regation laws regulating African access to urban areas. -

Arts 670 the Photographic Book

SPRING 2019 ARTS 670 THE PHOTOGRAPHIC BOOK Marion Belanger TEXTS: Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, The Photobook: A History Volume I, Phaidon Press, 2004 (If you can buy only one book for this course, make it this volume.) Parr and Badger, The Photobook, A History, Volume II, Phaidon Press, 2006 Nicholas Dawidoff, New York Times Magazine. “The Man Who Saw America,” http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/magazine/robert-franks-america.html For explanation of printing techniques: Richard Benson, The Printed Picture, The Museum of Modern Art, 2008 This class is both an introductory survey of the photographic book and a hands on studio course where students will make simple book sequences. Along with the readings, the photographic book will be studied while visiting collections in the Wesleyan Library, and the Yale University Art Gallery. Reading Assignments: The books mentioned above can be purchased, but they will also be on reserve in the library. Note that the weekly readings include a broader range of books than presented in class. A packet of additional readings will be available. Week 1 Introduction Bring in a favorite photo book from home or a photo sequence you’ve made in the past. Library Visit Assignment: Make photographs in your home/yard. Bring in a 10 5x7 images from the series to sequence in class. Reading: Richard Benson, The Printed Picture: Part 5: “Early Photography in Silver” and Part 6: “Non-Silver Processes.” Parr and Badger. The Photobook, A History, volume I. Introduction and Chapter 1, “Topography and Travel: The First Photobooks.” Week 2 Photographic albums at the dawn of the photographic era Anna Atkins. -

Photographer David Goldblatt Chronicled Apartheid in Profoundly Intimate Images - Artsy

07/09/2020 Photographer David Goldblatt Chronicled Apartheid in Profoundly Intimate Images - Artsy Search by artist, gallery, style, theme, tag, etc. Advertisement Art Photographer David Goldblatt Chronicled Apartheid in Profoundly Intimate Images Charlotte Jansen Sep 4, 2020 2:18pm David Goldblatt, Self-portrait at Consolidated Main Reef David Goldblatt Mines, Roodepoort, 1967. Courtesy of Goodman Gallery. Shop assistant, Orlando West, 1972 Goodman Gallery How can we understand violence? Over six decades and an extraordinary body of work, the legendary late photographer David Goldblatt sought to understand forms of violence—structural and primordial, visible and invisible—inicted not only human bodies and culture, but on the Earth itself. Goldblatt was born in 1930 in the gold-mining town of Randfontein; his grandparents had ed persecution of Jews in Lithuania and settled in South Africa in the late 19th century. He began taking photographs, Skip to Main Conatlebent it as an amateur, in 1948; that same year, South Africa’s right-wing https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-photographer-david-goldblatt-chronicled-apartheid-profoundly-intimate-images 1/15 07/09/2020 Photographer David Goldblatt Chronicled Apartheid in Profoundly Intimate Images - Artsy SearchN bya atritoisnt, agla llPerayr, styty lew, tahse meele, tcatge, edtc. .It was the beginning of nearly 50 years of apartheid. David Goldblatt David Goldblatt Rochelle and Samantha Adkins, Hillbrow, 1972 Anna Lebako, a washerwoman from Goodman Gallery Soweto carrying the week's laundry to a … Goodman Gallery By the time Goldblatt began his professional career in photography in 1962, South Africa was segregated in every sense—80% of the land was legally claimed for white people, forcing millions of Black South Africans from their homes. -

2014 – Autumn – the International Letter

ESHPh European Society for the History of Photography Association Européenne pour l’Histoire de la Photographie Europäische Gesellschaft für die Geschichte der Photographie The International Letter La lettre internationale Mitteilungen Autumn 2014 Vienna ESHPh: Komödiengasse 1/1/17 A - 1020 Vienna. Austria Phone: +43 (0) 676 430 33 65 E mail: [email protected] http://www.donau-uni.ac.at/eshph Dear Reader, This issue of our ESHPh International Letter presents you with a great deal of information on interesting conferences, fairs, exhibitions and research projects. We would like to draw your attention to this year’s Month of Photography that is celebrating its 10th anniversary with a huge variety of activities in several cities. More information regarding the activities of ESHPh can be found on our website: www.donau- univ.ac.at/eshph. Finally, we would like to inform you that our new issue of PhotoResearcher No 22 175 Years of Photohistory has just appeared. We hope you will find our recommendations interesting and wish you pleasant reading. Uwe Schögl Ulla Fischer-Westhauser President of the ESHPh Vice-president Vienna, October 2014 ESHPh - The International Letter - Autumn 2014 2 10th European Month of Photography (EMoP) Exhibitions and events: October - November 2014 In 2014, the European Month of Photography (EMoP) celebrates its 10th anniversary. The platform’s objective was and is to network and strengthen European photography; for example, by producing collaboratively curated photography exhibitions. This year’s joint exhibition Memory Lab. Photography Challenges History will be presented in Vienna and all partner cities Athens, Berlin, Bratislava, Budapest, Ljubljana, Luxembourg and Paris as part of their concurrent months of photography. -

Marian Goodman Gallery David Goldblatt

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY DAVID GOLDBLATT Birth 1930, Randfontein, South Africa Death 2018, Johannesburg, South Africa Awards: 2015 Kraszna-Krausz Fellowship Award 2013 ICP Lifetime Achievement award from the International Center of Photography, New York 2011 Honorary Doctorate San Francisco Art Institute 2011 Kraszna-Krausz Photography Book award (with Ivan Vladislavic) 2010 Lucie Award Lifetime Achievement Honoree 2009 Henri Cartier- Bresson Award, France 2008 Honorary Doctorate of Literature, University of Witwatersrand 2009 Lifetime Achievement Award, Arts and Culture Trust 2006 HASSELBLAD PHOTOGRAPHY AWARD 2004 “Rencontres d’Arles” Book Award for his book ‘Particulars’ 2001 Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts, University of Cape Town 1995 Camera Austria Prize SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 David Goldblatt: 1948-2018, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia David Goldblatt, Structures de domination et de démocratie, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France David Goldblatt, Librairie Marian Goodman, Paris 2016 Ex-Offenders, Pace Gallery, New York, USA 2015 Structures of Dominion and Democracy, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa David Goldblatt, The Pursuit of Values Standard Bank Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa 2014 Structures of Dominion and Democracy, Galerie Marian Goodman, Paris, France Structures of Dominion and Democracy in South Africa, Minneapolis Institute of Art, USA New Pictures 10: David Goldblatt, Structures of Dominion and Democracy, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, United States 2012 On the Mines, The Goodman -

Steidl WWP SS18.Pdf

Steidl Spring/Summer 2018 3 Index Contents Artists/Editors Titles Adams, Shelby Lee 63 1968 99 Paris Reconnaissance 113 3 Editorial 81 Orhan Pamuk Balkon Adams, Bryan 93 200 m 123 Paris, Novembre 95 4 Index 85 Christer Strömholm Lido Adolph, Jörg 14-15 42nd Street, 1979 61 Park/Sleep 49 5 Contents 87 Guido MocaficoLeopold & Rudolf Blaschka, The Bailey, David 103-109 8 Minutes 107 Partida 51 6 How to contact us Marine Invertebrates Baltz, Lewis 159 Abandoned Moments 133 Pictures that Mark Can Do 105 Press enquiries 89 Timm Rautert Germans in Uniform Bolofo, Koto 135-139 Abstrakt 75 Pilgrim 121 How to contact our imprint partners 91 Sory Sanlé Volta Photo Burkhard, Balthasar 71 Andreas Gursky 69 Poolscapes 131 93 Bryan Adams Homeless Callahan, Harry 151 Asia Highway 167 Printing 137 95 Sze Tsung, Nicolás Leong Paris, Novembre Clay, Langdon 61 B, drawings of abstract forms 25 Proving Ground 169 DISTRIBUTION 97 Shelley Niro Cole, Ernest 157 Bailey’s Democracy 104 Reconstruction. Shibuya, 2014–2017 19 99 Robert Lebeck 1968 7 Germany, Austria, Switzerland Collins, Hannah 149 Bailey’s East End 108 Regard 127 101 Andy Summers The Bones of Chuang Tzu 8 USA and Canada Davidson, Bruce 165 Bailey’s Naga Hills 109 Seeing the Unseen 153 103 David Bailey’s 80th Birthday 9 France Devlin, Lucinda 147 Balkon 81 Shelley Niro 97 104 David Bailey Bailey’s Democracy All other territories Dine, Jim 113 Ballet 145 Stories 5–7, Soweto—Dukathole—Johannesburg David Bailey Havana Edgerton, Harold 153 Balthasar Burkhard 71 129 105 David Bailey NY JS DB 62 11 Steidl Bookshops Eggleston, William 37-41 Binding 139 Structures of Dominion and Democracy 73 David Bailey Pictures that Mark Can Do 13 Book Awards 2017 Elgort, Arthur 145 Bones of Chuang Tzu, The 101 Synchrony and Diachrony, Photographs of the 106 David Bailey Is That So Kid Fougeron, Martine 119 Book of Life, The 63 J. -

The International Center of Photography Announces Appointment of David E

THE INTERNATIONAL CENTER OF PHOTOGRAPHY ANNOUNCES APPOINTMENT OF DAVID E. LITTLE AS NEW EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR New York, NY—August 10, 2021—The Board of Trustees of the International Center of Photography (ICP) announced today the selection of David E. Little as its new Executive Director, following an international search. Little will join ICP in mid-September 2021, after six years as director and chief curator of the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College, and will succeed Mark Lubell, who announced his departure in March 2021. “David brings to ICP an outstanding mix of skills and experiences, between his work as an educator, curator, fundraiser, and manager, and we are thrilled that he will be joining us,” said Jeffrey Rosen, ICP’s Board President. “His wide-ranging roles at leading institutions both within and outside of New York City make clear that he understands the different but interrelated elements of exhibitions, education, and community engagement that make ICP unique, which in turn made him the clear choice for our new Executive Director.” Little’s tenure at the Mead Art Museum at Amherst was marked by a record of successful fundraising, collection growth and diversification, and institutional planning that has strengthened the Mead’s curatorial program and its educational role within Amherst’s liberal arts curriculum. Little’s prior positions include time as the Curator and Department Head of Photography and New Media at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Associate Director and Head of Education at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Director of Adult and Academic Programs at the Museum of Modern Art. -

RAM PUB SPRNG-15 FINAL.Indd

publications + distribution spring 2015 spring 2015 Architecture 5 Art + Culture 8 Design + Graphics 29 Photography 34 Theory + Literary Arts 40 Previously Announced 50 RAM ORDeR + TRADe InfORMATIOn 52 rampub.com Art Architecture + Culture Highlights XXII CEMEX BUILDING AWARD Produced now for over 20 years, this comprehensively illustrated volume documents the winners of the 2015 renowned building award sponsored by international concrete, cement and aggregates giant CeMeX, based in Mexico. Chosen by a prestigious jury of 17 international and domestic architects, engineers and designers, the prize-winners span 13 categories, from single-family and multi-unit residential (both conventional and low-income) to commercial and mixed-use, accessibility, social impact, urbanism, infrastructure, innovation in techniques and construction processes and sustainability. Also awarded is a Lifetime Achievement Award, this year given to Spanish architect Carlos ferrater i Lambarri. The book is an indispensible reference on current architecture and building technologies for libraries, architects, designers and engineers. A stunning publication filled with full-color plates and informative essays. January 2015, english & Spanish ARQUIe n , MeXICO Hardcover, 9 x 11 ¼ inches CeMeX, MeXICO 284 pp, extensive color ISBn: 978-607-7784-69-2 Retail price: $42.50 49 CITIES WORKac (ed.) The much-in-demand 49 Cities, first published by Storefront for Art & Architecture, the internationally recognized nYC center for alternative thinking in art and architecture, is now available in its third edition. This fascinating compilation of “fantastic projections” by architects and planners dreaming of better and different cities ranges from 500 B.C. to the present. With every plan, radical visions were proposed, embodying not only desires but also fears and anxieties of the time. -

A Companion to Digital Art WILEY BLACKWELL COMPANIONS to ART HISTORY

A Companion to Digital Art WILEY BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO ART HISTORY These invigorating reference volumes chart the influence of key ideas, discourses, and theories on art, and the way that it is taught, thought of, and talked about throughout the English‐speaking world. Each volume brings together a team of respected international scholars to debate the state of research within traditional subfields of art history as well as in more innovative, thematic configurations. Representing the best of the scholarship governing the field and pointing toward future trends and across disciplines, the Blackwell Companions to Art History series provides a magisterial, state‐ of‐the‐art synthesis of art history. 1 A Companion to Contemporary Art since 1945 edited by Amelia Jones 2 A Companion to Medieval Art edited by Conrad Rudolph 3 A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture edited by Rebecca M. Brown and Deborah S. Hutton 4 A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art edited by Babette Bohn and James M. Saslow 5 A Companion to British Art: 1600 to the Present edited by Dana Arnold and David Peters Corbett 6 A Companion to Modern African Art edited by Gitti Salami and Monica Blackmun Visonà 7 A Companion to Chinese Art edited by Martin J. Powers and Katherine R. Tsiang 8 A Companion to American Art edited by John Davis, Jennifer A. Greenhill and Jason D. LaFountain 9 A Companion to Digital Art edited by Christiane Paul 10 A Companion to Public Art edited by Cher Krause Knight and Harriet F. Senie A Companion to Digital Art Edited by Christiane Paul -

David Goldblatt Ex Offenders at the Scene of Crime

david goldblatt Ex Offenders at the Scene of Crime September - October 2012 opening: thursday, September 20th, According to David Goldblatt, his recent photographic project Ex Offenders at the Scene of Crime – a series of por- traits of individuals convicted of having committed crimes in South Africa, where crime rates are among the highest in the world, and the threat of crime an inescapable part of daily life for every stratum of society -- began as a question: My interest in ex-offenders arises from a wish to know who are the people who are doing the crimes and to get a sense of their life and how they came to crime. Could these people be my children? Could they be you? Or me? I have no ‘agenda’. Perhaps that is why very often ex-offenders talk very openly to me. I am not a magistrate or a judge or a lawyer or a social worker or an activist. I think that for some, this has been the first opportunity they have had to tell their story without being judged. The answer to Goldblatt’s questioning is Ex Offenders at the Scene of Crime, a gripping series of photograph-and-text portraits currently on view at the Elba Benitez Gallery. The photographs in Ex Offenders follow a basic format. Each is a medium-size black-and-white photographic portrait taken at the site where a crime was committed. All are accompanied by ‘statements’ about the crimes based on the words of their perpetrators – petty shoplifters, celebri- ty bank robbers, rapists, thieves, jealous lovers, police torturers and murderers. -

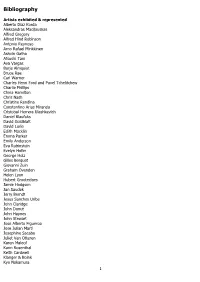

Bibliography

Bibliography Artists exhibited & represented Alberto Diaz Korda Aleksandras Macijauskas Alfred Gregory Alfred Hind Robinson Antonio Reynoso Arno Rafael Minkkinen Ashvin Gatha Atsushi Tani Ava Vargas Borje Almquist Bruce Rae Carl Warner Charles Henri Ford and Pavel Tchelitchew Charlie Phillips China Hamilton Chris Nash Christine Rendina Constantino Arias Miranda Cristobal Herrera Ulashkevich Daniel Blaufuks David Goldblatt David Lurie Edith Macklin Emma Parker Emily Anderson Eva Rubinstein Evelyn Hofer George Holz Gilles Berquet Giovanni Zuin Graham Ovenden Helen Lyon Hubert Grooteclaes Jamie Hodgson Jan Saudek Jerry Berndt Jesus Sanches Uribe John Claridge John Donut John Haynes John Stewart Jose Alberto Figueroa Jose Julian Marti Josephine Sacabo Juliet Van Otteren Karen Maloof Karin Rosenthal Keith Cardwell Klanger & Boink Kyo Nakamura 1 Lazaro Miranda Vera Lewis Morley Lewis Wickes Hine Lilo Raymond Margaret Casson (nee McDonald) Marie Andersson Mario Diaz Leyva Martin H.M. Schreiber Mick Lindberg Michael Woods Mike Roles Masaaki Toyoura Michel Hanique Morel Derfler Omar Badsha Paul Caffell Paul Kilsby Pedro Abascal Peter Bromley Phil Stern Phillip Trager Pierre Louys Pilar Macias Ralph Eugene Meatyard Raul Canibano Ercilla Raul Corrales Fornos Richard K Diran Richard Lancelyn Green Collection Richard Sawdon Smith Robin Hanbury-Tenison Russ Karel Sean Hillen Taneli Eskola Tansy Spinks Terry King Trevor Watson Vee Speers Veronica Sive Victor Sloan Wallace Wilson Wilhelm Moser William Carter William Ingram Willy Ronis Wolfgang Suschitzky