Shahnameh and Later Persian Epics1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Journal of Physical Education and Sport Science

European Journal of Physical Education and Sport Science ISSN: 2501 - 1235 ISSN-L: 2501 - 1235 Available on-line at: www.oapub.org/edu doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3530881 Volume 5 │ Issue 12 │ 2019 WRESTLING IN TURKIC PEOPLES FROM A SOCIO-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE Mehmet Türkmen1, Cengiz Buyar2 1Professor Dr., Muş Alparslan University & Kyrgyzstan-Turkey Manas University, Traditional Sports and Games Research & Application Center, Turkey and Kyrgyzstan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5926-7522 2Assoc. Dr. Kyrgyzstan-Turkey Manas University, Head of Department of Turcology, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0549-4463 Abstract: This monograph will address the following questions: “What was the perspective of Turkic peoples on wrestling branch of sports and what was the cultural aspect of wrestling for social structures and lifestyles of Turkic peoples? What type of a transformation did wrestle experience? What is its current state at national level?” Problem: The problem of this research pertains to the fact that the richness of traditional wrestling which is known to possess a deep-seated reputation in Turkish history of sports and occupy an affluent position in Turkish sports tradition is not well- reflected in the literature at national and international levels, its traditional cultural elements are lost along with globalization and it is likely to end up being almost erased from national memories. Objective: This modest study sought to find an answer to the question as to how Turkic peoples perceived traditional wrestling in religious, national, political, military, economic and social domains of life and aimed to incorporate the finding into the literature rightly. Methodology: From among qualitative research methods, descriptive and comparative research techniques were implemented in this study. -

Paradosiaki Pali in Central Macedonia, Greece Pelivansko Borenje in FYR Macedonia Contacts in South-East Europe Other Traditional Wrestling Styles in Europe

Traditional Wrestling Our Culture Promoting Traditional Sports and Games Intangible Cultural Heritage In South-East Europe Edited by Guy Jaouen and Petar Petrov Published by Associazione Giochi Antichi (Ancient Games Association), ITALY AGA Verona 2018 Printed and bound in Bulgaria by GUTENBERG PUBLISHING HOUSE Acknowledgements This project and this book are the result of a work started in the year 2005. But in fact it is result of a life of commitment for several of the actors, either as wrestler, as leader or as researcher. It is also the result of the work of many friends and supporters of traditional wrestling and traditional sports and games in general, and we are sorry to not be able to mention all of them. Associazione Giochi Antichi: Paolo Avigo, Emanuele Tagetto, Simona Puggioni (Italy) ; Association Europeénne des Jeux et Sports Traditionnels: Bartosz Prabucki & G.J. ; Federatia Romana de Oina: Nicolae Dobre, Cristian Federación de Lucha Leonesa: Antonio Barreñada and Francisco Escanciano (Spain); Institute of Ethnology and FolkloreVăduva and Studies: Ionut Morcan Nikolai (Romania);Vukov & P.P. (Bulgaria); Tranta: Ardelean Gheorghe, Federacija za pelivansko borenje na Makedonija: Hamid Bakija and Faruk Dan Buzea, Szabolcs LörinczFédération Konya and Congolaise Peter-Ferenc de Kabubu: Taierling (Romania); Kures: Aydan & Nida Ablez Rexhepi (FYR Macedonia); Narodno rvanje: Joseph Rashidi Salumu and Musongela Mambo Rashidi (Congo);Paradosiaki Pali: Anta Tsaira, and Amet Sehran (Romania); Marko Panović, Aca Stanojević, CharalamposDejan -

Leader Names Two New Deputy Commanders for IRGC

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 16 Pages Price 40,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13391 Saturday MAY 18, 2019 Ordibehesht 28, 1398 Ramadan 12, 1440 Younger generations Will cotton waste stalks Persepolis Iran seeks to screen films must be trusted, accelerate wound lift IPL title for third from Varesh festival in cleric says 3 healing? 11 successive year 15 ECO member states 16 Tehran, Damascus discuss Leader names two new expansion of economic ties TEHRAN — Hassan Danaeifar, the ties between Iran and Syria. advisor to Iran’s first vice president During the meeting, Nadaf stressed and also the chairman of the Iranian the significance of current cooperation deputy commanders for IRGC committee on development of economic between his country and Iran in the relations with Syria and Iraq, and Atef reconstruction projects in Syria, IRNA Nadaf, the Syrian minister of interi- reported on Thursday. See page 3 or trade and consumer protection, met Danaeifar for his part announced Iran’s in Damascus to explore the ways for readiness for more cooperation with Syria expanding and strengthening economic in these projects. 4 Russia, China should take practical measures to save JCPOA: Zarif TEHRAN — Russia and China must “China is an important partner take practical measures if they want to of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” he protect the achievements of the nuclear said. “China is one of the remaining deal, officially called the Joint Com- members to Barjam (JCPOA) and it is prehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), important to hold consultations with Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad the Chinese side, especially with re- said on Friday. -

Art Moderne Et Contemporain Arabe Et Iranien Art Moderne Et Contemporain

ART MODERNE ET CONTEMPORAIN ARABE ET IRANIEN ART MODERNE ET CONTEMPORAIN PARIS ART MODERNE ET CONTEMPORAIN ARABE ET IRANIEN MAISON DE VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES - AGRÉMENT N° 2001-005 7, Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées – 75008 Paris Tél. : +33 (0)1 42 99 20 20 – Fax : +33 (0)1 42 99 20 21 2009 SAMEDI 24 OCTOBRE PARIS – HÔTEL MARCEL DASSAULT www.artcurial.com – [email protected] SAMEDI 24 OCTOBRE 2009 – 16H30 01706 DÉPARTEMENTS D’ART ART MODERNE BIJOUX DESIGN Violaine de La Brosse-Ferrand Ardavan Ghavami, consultant international Fabien Naudan, directeur associé directeur associé, +33 (0)1 42 99 20 32 +33 (0)1 42 99 16 30 +33 (0)1 42 99 20 19 Bruno Jaubert, spécialiste Thierry Stetten, expert Harold Wilmotte, spécialiste junior +33 (0)1 42 99 20 35 Julie Valade, spécialiste +33 (0)1 42 99 16 24 Nadine Nieszawer, consultant pour les œuvres de +33 (0)1 42 99 16 41 contact : Alma Barthélémy l’École de Paris, 1905-1939 contact : Alexandra Cozon +33 (0)1 42 99 20 48 contacts : Tatiana Ruiz Sanz +33 (0)1 42 99 20 58 +33 (0)1 42 99 20 34 AUTOMOBILES DE COLLECTION MONTRES Jessica Cavalero François Melcion, spécialiste +33 (0)1 42 99 20 08 Romain Réa, expert +33 (0)1 42 99 16 31 Priscilla Spitzer, catalogueur contact : Julie Valade Marc Souvrain, expert +33 (0)1 42 99 20 65 +33 (0)1 42 99 16 41 +33 (0)1 42 99 16 37 Constance Boscher Frédéric Stœsser, consultant CURIOSITÉS, CÉRAMIQUES recherche et authentification +33 (0)1 42 99 16 38 ET HAUTE ÉPOQUE +33 (0)1 42 99 20 37 Wilfrid Leroy-Prost, spécialiste junior Robert Montagut, expert +33 (0)1 42 99 16 -

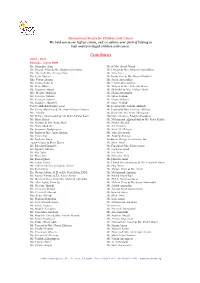

2004-2011 Contributors In-Kind

International Society for Children with Cancer We hold you in our highest esteem, and we admire your spirit of helping us help underprivileged children with cancer. Contributors 2004 – 2011 Friends - Up to $999 Dr. Alexander Alam Mr. & Mrs. Sivash Nejad Mr. Behzad Abadi & Ms. Maryam Khosravani Mr. Hisham & Mrs. Afsaneh Alameddine Mr. Alireza & Mrs. Arezoo Abaye Ms. Zina Alavi Ms. Leyla Abazari Mr. Farid Alavi & Ms. Marjan Khalitchi Mrs. Parvin Abazari Ms. Susan Alavi Sullins Ms. Besma Abbaoui Ms. F Alavi-Maroufkhani Mr. Reza Abbasi Mr. Mehran & Mrs. Mehrzad Alemi Ms. Yasaman Abbasi Mr. Shahrokh & Mrs. Afshan Alemi Mrs. Mojdeh Abbasian Ms. Homa Alemzadeh Ms. Freshteh Abbassi Mr. Sasha Aliabadi Ms. Yasaman Abbassi Ms. Diana Aliabadi Ms. Seddighe Abdollahi Mr. Sasan Aliabadi F & N Abdollahi Family Trust Mr. Javad & Mrs. Soheila Aliabadi Ms. Hoora Abdolreza & Mr. Seyd Afshean Hessam Mr. Farshad & Mrs. Farahnaz Alikhani Mrs. Abedini Mr. Russell & Mrs. Sonia Alimagham Mr. Bizhan Abedinzadeh & Ms. Hehieh Parsa Pasir Marylinn`s Couture Bridal of Pasadena Ms. Mina Abhari Mr. Mohammad Alipour Jeddi & Ms. Shiva Kolahi Mr. Sherwin & Mrs. Roya Abidi Ms. Sholeh Alizadeh Ms. Neda Abolfathi Mr. Ali Alizadeh Mr. Faramarz Abolghassem Ms. Effat M. Allahyari Mr. Ruben & Mrs. Azita Abrams Ms. Tala Altoontash Ms. Farah Abri Mr. Andrew Ahmadi Mr. Shahram Abyari Ambiance Design Consultants, Inc. Action Carpet & Floor Decor Ms. Sheri Ameri Ms. Bita Adelfahmideh Mr. Farrokh & Mrs. Marie Ameri Ms. Sepideh Adhami Ms. Farahnaz Amid Ms. Kat Adibi Ms. Fali Amin Dr. Bijan Afar Ms. Parvaneh Amin Mr. Sam Afghani Mr. Jahanfar Amin Ms. Ladan Afshar Mr. Hamid Reza Shafipour & Ms. -

Regulation of the Third World Nomad Games

REGULATION OF THE THIRD WORLD NOMAD GAMES CHOLPON-ATA KYRGYZ REPUBLIC SEPTEMBER 2-8, 2018 I. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES Building on ethno cultural heritage of the peoples of the world, the World Nomad Games (hereinafter referred to as the WNG III) have the following goals and objectives: 1. Develop the world ethno sports movement; 2. Popularize and expand ethno sports types, traditional games and competitions of the peoples of the world in the international arena; 3. Preserve historical and cultural heritage and diversity of the peoples of the world in the era of globalization; 4. Promote scientific and organizational and methodological approach to ethno movement, ethno sports, traditional games and competitions of the peoples of the world; 5. Contribute to strengthening and further development of interreligious and intercultural dialogue, mutual understanding, friendship, harmony and cooperation among the peoples of the world, and demonstrate their cultural diversity. II. DATE AND VENUE The World Nomad Games are held every two years. Dates: September 2-8, 2018. Location: Cholpon-Ata, Issyk-Kul province, Kyrgyz Republic. Sports delegations’ arrival dates: August 31 - September 1, 2018. Sports delegations registration: August 31- September 1, 2018. Opening ceremony: September 2, 2018. Closing ceremony: September 8, 2018. Sports delegations’ departure date: September 9, 2018 before 12.00 PM. III. PARTICIPATION AND ADMISSION TERMS Only countries that submit their applications in a timely manner are allowed to participate in WNG III (application submission terms are attached hereto in Section IX). Each unit of a federal state has the right to present their teams 1(terms of unofficial team ranking are attached hereto in Section XI). -

Endangered Species of the Physical Cultural Landscape: Globalization, Nationalism, and Safeguarding Traditional Folk Games

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 3-17-2021 9:00 AM Endangered Species of the Physical Cultural Landscape: Globalization, Nationalism, and Safeguarding Traditional Folk Games Thomas Fabian, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Barney, Robert K., The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in Kinesiology © Thomas Fabian 2021 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fabian, Thomas, "Endangered Species of the Physical Cultural Landscape: Globalization, Nationalism, and Safeguarding Traditional Folk Games" (2021). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7701. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7701 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Folk sports are the countertype of modern sports: invented traditions, bolstered by tangible ritual and intangible myth, played by the common folk in order to express a romantic ethnic identity. Like other cultural forms, traditional sports and games around the world are becoming marginalized in the face of modernization and globalization. In 2003, UNESCO ratified the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in an attempt to counter such trends of cultural homogenization. As elements of intangible cultural heritage, folk sports now fall under the auspices of UNESCO safeguarding policies. -

Technical Handbook Belt Wrestling, 5Th AIMAG Ashgabat 2017

Sport Handbook Belt Wrestling September2017 Publication name Belt Wrestling Sport Handbook 5th Asian Indoor And Martial Arts Games – in honor of peace and friendship On behalf of the Country of Turkmenistan, I would like to welcome all of our guests who are coming to participate at Ashgabat 2017 5th Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games, taking place for the first time in our country. We are working hard across all levels of the government to develop sport in Turkmenistan, and are working together with International Federations and sporting organisations throughout the world to share knowledge and experience. I hope that Ashgabat 2017 will establish Turkmenistan’s position on an international level, spread our Country’s love of sport throughout the world and strengthen our friendly relations between nations. During the Games, Asian and Oceanic athletes will have the opportunity to share their experiences, demonstrate their sporting skills and build lasting friendships. We have been working hard to deliver the Games to a high level. The Ashgabat Olympic Complex covers total area of 157km2, we have over 30 different sites within the complex, including 15 sport competition venues. The Athletes village and accommodation for our guests offers I would like to express my gratitude to the heads of the international world class catering, relaxation, cultural and entertainment Olympic Council of Asia for the support and opportunity to facilities. All of this contributes to the great experience we want our host the 5th Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games and I guests to have along with a greater cooperation with Asian, Oceanic and would also like to thank the heads of the Asian and Oceania international sport federations. -

World Nomad Games 2018 Program

PROGRAM OF SPORTS AND CULTURAL EVENTS OF THE THIRD WORLD NOMAD GAMES № Location Type of sport Events Timeline 1st of September, 2018 (Saturday) FOK, Gushtini milli kamarbandi Weighing in places of residence 16:00 – 17:00 Cholpon-Ata city (Tajik wrestling) 2nd of September, 2018 (Sunday) Gushtini milli kamarbandi Opening ceremony 09:00 – 09:10 FOK, (Tajik wrestling) (carpet А,В, Preliminary fights 09:10 – 13:00 Cholpon-Ata city С) Final fights, award ceremony 13:00 – 14:30 Alysh wrestling Weighing in places of residence 10:00 – 12:00 Toguz korgool Draw 9:00 – 9:20 Mangala Draw 9:20 – 9:40 Ovari Draw 9:40 – 10:00 Toguz korgool Round I 10:00 – 12:00 Mangala Round I 14-00 – 14:40 Ovari Round I 15-00 – 15:40 Kok-Boru The draw for the teams in the places of residence 16:00 – 18:00 Hippodrome, Cholpon-Ata city The official opening ceremony of the III WNG 20:00 – 23:00 3rd of September, 2018 (Monday) Kok-Boru Opening ceremony 09:00– 09:30 Hippodrome, Preliminary games in subgroups 09:30 – 18:30 Cholpon-Ata city Remote run for 80 km. The brood of horses, the credentials Committee (jockey) 16:00 – 18:00 Tug of the rope 1х1, 8х8 Registration of participants 16:00 – 18:00 (jockey) Pahlavani (traditional Iranian Weighing in places of residence 16:00 – 17:00 FOK, wrestling), goresh (Turkmen Cholpon-Ata city wrestling), Kazakh kures (Kazakh national wrestling) Toguz korgool Round II 10:00 – 12:00 Mangala Round II 15:00 – 15:40 Ovari Round II 17:00 – 17:40 Arm wrestling Preliminary fights 10:00 – 11:00 Outdoor stage FOK, Opening ceremony 11:00 – 11:30 Cholpon-Ata city Continuation of preliminary fights 11:30 – 15:30 Final fights, award ceremony 15:30 – 17:00 Mas-wrestling Weighing in places of residence 16:00 – 18:00 Cultural program Rehearsal of the official opening of the theatrical performance "Golden century of nomads." 10:00-12:00 Arrival of heads of state and officials headed by the 14:30 President of the Kyrgyz Republic S. -

Belt Wrestling Technical Handbook

Belt Wrestling Technical Handbook 2019 Chungju World Martial Arts Masterships Organizing Committee Ⅰ. Introduction 1. Preface ···································································································· 3 2. Organization Bodies(WMC, 2019 Chungju WMOC) ·················· 4 Ⅱ. General Information 1. 2019 Chungju World Martial Arts Masterships in Brief ·········· 6 2. Accreditation and Validation ····························································· 7 3. Immigration and Visa ········································································ 8 4. Transportation ····················································································· 8 5. Accommodation ················································································· 9 6. Media ···································································································· 9 7. Medical Service ··················································································· 9 8. Host Country/City Information ··················································· 10 Ⅲ. Technical Information 1. Competition Date ············································································ 13 2. Venue ·································································································· 13 3. Competition Management ···························································· 13 4. Competition Events ········································································ 13 5. Competition Schedule ···································································· -

The Shahname of Firdowsi

The Shahname of Firdowsi The Shahname of Firdowsi by Iraj Bashiri copyright, Bashiri 1993, 2003 and 2008 Introduction The conflict between the present-day Uzbeks and their Tajik neighbors that is at times inflamed has a long and multi-faceted history. On the one hand, it is related to the ancient history of the two peoples, when the Turks, arriving in Central Asia from the confines of Mongolia, overthrew Iranian rule, including Tajik rule. And, on the other hand, it is related to the resilience of the Tajik culture and the ability of the Tajiks to retain their authority in spite of the might of the Turkish sultans and amirs. In recent decades, especially after the fall of the Soviet Union, the Turks revived Pan-Turkism, once again denying the Tajiks their identity. In this regard, they often cite Afrasiyab from the epic of Firdowsi, as the eponymous ancestor of the Turks. This claim presents several difficulties. First, both in the ancient Iranian texts and in Firdowsi's Shahname, Afrasiyab is a mythical character. He is not the real-world king that, for instance, al-Tabari would like us to believe.[1] Secondly, within the myth, he is a Turanian who has lost his farr (kingly glory) and seeks to restore it. This means that the Turanians of the Shahname are of Iranian stock. Thirdly, a review of the Orkhon inscriptions and life on the steppe indicates that neither the Turanians nor the Iranians of the Shahname share the öz (real) Turk cultural heritage of which the Turks are proud. -

Basic Movement Standardization of the Pathol Sarang Martial Sport

Medico-legal Update, January-March 2021, Vol. 21, No. 1 1591 Basic Movement Standardization of the Pathol Sarang Martial Sport Putra Budi Kutniawan1, Tandiyo Rahayu2, Heny Setyawati2, Mugiyo Hartono2 1Doctoral Student, Post Graduate Dept., Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia, 2Lecture, Post Graduate Dept., Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia Abtract The purpose of this research is to make standardization of the basic movements of the pathol martial arts sport which is intended to identify the basic movements of the pathol martial arts by using logical science principles so that it can be used/played by everyone, then it can provide convenience in its development so that the traditional Pathol martial arts can be easily learned by the public. In general, the research approach used in this research is descriptive qualitative using a case study research design. This approach is used because the focus is on testing one phenomenon, namely the basic motion of the pathol nest martial arts. It takes careful preparation in determining participants, places, and data collection because this research is changing and developing according to changes in findings in the field. a place where researchers conduct research. This research was conducted in the coastal area of Sarang sub-district (Bajingjowo village, Temperak village, and Karangmangu village), which is the only area that still maintains the pathol nest martial arts. The focus of this research is to examine in depth the classification of the basic movements of pathol martial arts through identification and then analysis by paying attention to scientific principles that will produce standard pathol basic motion. This research is studied through philosophical studies, sociological studies, motor learning studies, sports biomechanics studies, and psychological studies.