Integrated Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shetland 2PHF104

shetland 2PHF104 2PHF104 shetland 2PHF114 shetland shetland Colours Balta Oxna Unst Linga 2PHF101 2PHF102 2PHF103 2PHF104 Decors and mixes Bigga Mousa Trondra Foula 2PHF105 2PHF106 2PHF107 2PHF108 supplying your imagination shetland Decors and mixes Muckle Whalsay Yell Vaila 2PHF109 2PHF110 2PHF111 2PHF112 Papa Noss 2PHF113 2PHF114 supplying your imagination shetland Wall mixes *Selected tiles are available in a Matt finish and suitable for walls only. 2PHF116 Lamba* Samphrey* 2PHF115 2PHF116 Bressay* Fetlar* 2PHF117 2PHF118 supplying your imagination Appearance: Patterned Material: Porcelain shetland Usage: Floors and Walls Sizes and finishes 200x200 600x600 800x800 800x1800 1200x1200 8mm 10/20**mm 11mm 11mm 11mm All colours Matt R10 (A+B) Anti Slip R11 (A+B+C) Notes **600x600x20mm is only available in Anti Slip R11 (A+B+C). Decors and mixes are available in size 200x200x8mm in a Matt R10 (A+B) finish. Tiles may display slight variations in print and tone. Please ask for details. Special pieces Square and round top plinths and step treads are available in all colours. For more information contact our sales team. Square and Round Step Treads Top Plinths ISO 10545 results 2 Dimensions and Surface Quality Conforms 10 Moisture Expansion No ratings 3 Water Absorption < 0.5% 12 Frost Resistance Conforms 4 Flexural Strength > 35 N/mm² 13 Chemical Resistance Conforms 6 Deep Abrasion Resistance No ratings 14 Stain Resistance Class 4 2PHF106 8 Linear Thermal Expansion < 9x10-6 °C Slip Resistance Matt R10 (A+B) (DIN 51130-51097) Anti Slip R11 (A+B+C) 9 Thermal Shock Resistance Conforms On request tiles can be tested to PTV BS7976-2. -

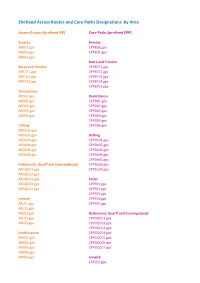

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Codes by Area

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Designations by Area Access Routes (prefixed AR) Core Paths (prefixed CPP) Bressay Bressay ARB01.gpx CPPB01.gpx ARB02.gpx CPPB02.gpx ARB03.gpx Burra and Trondra Burra and Trondra CPPBT01.gpx ARBT01.gpx CPPBT02.gpx ARBT02.gpx CPPBT03.gpx ARBT03.gpx CPPBT04.gpx CPPBT05.gpx Dunrossness ARD01.gpx Dunrossness ARD03.gpx CPPD01.gpx ARD04.gpx CPPD02.gpx ARD05.gpx CPPD03.gpx ARD06.gpx CPPD04.gpx CPPD05.gpx Delting CPPD06.gpx ARDe01.gpx ARDe02.gpx Delting ARDe03.gpx CPPDe01.gpx ARDe04.gpx CPPDe02.gpx ARDe06.gpx CPPDe03.gpx ARDe08.gpx CPPDe04.gpx CPPDe05.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh CPPDe06.gpx ARGQC01.gpx CPPDe07.gpx ARGQC02.gpx ARGQC03.gpx Fetlar ARGQC04.gpx CPPF01.gpx ARGQC05.gpx CPPF02.gpx CPPF03.gpx Lerwick CPPF04.gpx ARL01.gpx CPPF05.gpx ARL02.gpx ARL03.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh ARL04.gpx CPPGQC01.gpx ARL05.gpx CPPGQC02.gpx CPPGQC03.gpx Northmavine CPPGQC04.gpx ARN01.gpx CPPGQC05.gpx ARN02.gpx CPPGQC06.gpx ARN03.gpx CPPGQC07.gpx ARN04.gpx ARN05.gpx Lerwick CPPL01.gpx Nesting and Lunnasting CPPL02.gpx ARNL01.gpx CPPL03.gpx ARNL02.gpx CPPL04.gpx ARNL03.gpx CPPL05.gpx CPPL06.gpx Sandwick ARS01.gpx Northmavine ARS02.gpx CPPN01.gpx ARS03.gpx CPPN02.gpx ARS04.gpx CPPN03.gpx CPPN04.gpx Sandsting and Aithsting CPPN05.gpx ARSA04.gpx CPPN06.gpx ARSA05.gpx CPPN07.gpx ARSA07.gpx CPPN08.gpx ARSA10.gpx CPPN09.gpx CPPN10.gpx Scalloway CPPN11.gpx ARSC01.gpx CPPN12.gpx ARSC02.gpx CPPN13.gpx Skerries Nesting and Lunnasting ARSK01.gpx CPPNL01.gpx CPPNL03.gpx Tingwall, Whiteness and Weisdale CPPNL04.gpx -

Shetland-Pony-Catalogue-09.Pdf

in association with Aberdeen & Northern Marts CATALOGUE OF SHOW AND SALE OF PEDIGREE SHETLAND PONIES (IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SHETLAND PONY STUD-BOOK SOCIETY) within Shetland Rural Centre, Staneyhill, Lerwick, Shetland. SHOW : Thursday 8th October 2009 at 5.00 pm SALE : Friday 9th October 2009 at 9.15 am PROMPT Staneyhill, Lerwick, Shetland Tel: 01595 696300 Fax: 01595 696305 Catalogue £2.00 CONDITIONS / GUIDELINES FOR SALES HELD If mares have not been covered in the current season, this must be stated UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE SOCIETY 14. In the interests of welfare, working ponies of four years old or over only may be clipped. 1. Premises must conform to all current animal welfare regulations. 15. Passports for all ponies that require one legally will be checked by Society 2. Ponies must not be removed from pens without the owner or his/ her officials. Should a passport be found to be incorrect, a charge of £5 will be representative being present. payable to the Society before the pony will be permitted to go through the 3. At all Sales, if the owner is not present in person, a representative must be ring. nominated in advance who will be responsible for the ponies. 16. A draft schedule must be lodged with the SPS-BS Secretary at least three 4. The entry form must include a declaration stating that the pony/ies being entered weeks prior to printing. Printing must not commence until approval has been in the Sale have been correctly transferred through the Society and are given by the Society. -

Central Mainland the Heart of Shetland Research Facilities for Scientific and Technological Projects Relating to the Fishing and Aquaculture Industries

Central Scalloway’s Westshore Public art on New Street Mainland Out at Port Arthur the marina and Scalloway Boating Club offer a safe haven and a warm welcome for visiting boats and their crews. Next to the boating club is the NAFC Marine Centre, the Centre offers training in nautical studies and Central Mainland The heart of Shetland research facilities for scientific and technological projects relating to the fishing and aquaculture industries. It also houses an excellent fish restaurant. Traditional boats drawn up on shore recall Shetland’s Some Useful Information fishing past. In Norse times Scalloway (‘the bay of the Accommodation: VisitShetland hall’) may have been the home of an important landowner Tel: 08701 999440 or official. Airport (inter-island): Tingwall Tel: (01595) 840246 Scalloway’s other attractions include a heated 17-metre Neighbourhood Scalloway Post Office indoor swimming pool, the youth centre, a hotel, guest Information Point Shetland Jewellry, Weisdale houses, cafes, pubs, shops and playing fields. Shops: Hamnavoe; Scalloway; Throughout the village are a number of works of public Whiteness; Weisdale art including sculptures done in Hildasay granite and Petrol: Burra; Weisdale flower tubs recycled from tractor wheels and tyres. Public toilets: Hamnavoe; Meal Beach; Scalloway Pubs and places to eat: Scalloway; Tingwall; Whiteness; Weisdale Post Offices: Hamnavoe; Weisdale; Scalloway Public telephones: Scalloway; Burra; Tingwall; Whiteness; Weisdale Museums and The NAFC Marine Centre overlooks the entrance to Scalloway Harbour Heritage Centres Scalloway, Burra Swimming pool: Scalloway Tel: (01595) 880745 Churches: Burra; Scalloway; Whiteness; Weisdale; Girlsta; Tingwall Doctor and Health Centre: Scalloway Tel: (01595) 880219 Police Station: Scalloway Tel: (01595) 880222 Contents copyright protected – please contact Shetland Amenity Trust for details. -

NSA Special Qualities

Extract from: Scottish Natural Heritage (2010). The special qualities of the National Scenic Areas . SNH Commissioned Report No.374. The Special Qualities of the Shetland National Scenic Area Shetland has an outstanding coastline. The seven designated areas that make-up the NSA comprise Shetland’s scenic highlights and epitomise the range of coastal forms varying across the island group. Some special qualities are generic to all the identified NSA areas, others are specific to each area within the NSA. The seven individual areas of the NSA are : Fair Isle, South West Mainland, Foula, Muckle Roe, Eshaness, Fethaland , and Hermaness . Where a quality applies to a particular area, the name is highlighted in bold . • The stunning variety of the extensive coastline • Coastal views both close and distant • Coastal settlement and fertility within a large hinterland of unsettled moorland and coast • The hidden coasts • The effects and co-existence of wind and shelter • A sense of remoteness, solitude and tranquillity • The notable and memorable coastal stacks, promontories and cliffs • The distinctive cultural landmarks • Northern light Special Quality Further information • The stunning variety of the extensive coastline Shetland’s long, extensive coastline is South West Mainland , stretching from Fitful Head (Old highly varied: from fissured and Norse hvitfugla, white birds) to the Deeps, displays greatly contrasting coastlines: fragmented hard rock coasts, to gentler formations of accumulated gravels, • Cliffed coastline of open aspect in the south to long voes sands, spits and bars; from remarkably at Weisdale and Whiteness. • Numerous small islands and stacks, notably in the area steep cliffs to sloping bays; from long, west of Scalloway. -

Supplementary Material Study Area Clift Sound Lies South of Shetland

Supplementary Material Study area Clift Sound lies south of Shetland, the islands of Trondra and East Burra to the west. It has steep- sides and a relatively unrestricted geomorphology (Fig. 1a). Two main types of soil are present in the catchment of Clift Sound: humus-iron podzols cover the islands of East Burra and Trondra, while peaty soils dominate the eastern coast of Clift Sound. Winds are generally from the southwest and, due to the geometry of the sound and the surrounding highlands, can be channelled and result in intensified currents. Tidal energy can also be channelled into more vigorous currents (Cefas 2007a). Sand Sound is located in the southwest of Shetland (Fig. 1a) and comprises three areas: the head of the voe, the inner basin and the outer basin. The head of the voe, a sheltered area, receives freshwater from a significant number of rivers draining the surrounding land. Three main types of soil characterise this area: peaty gleis, peaty podzols and peaty rankers. Here, the voe is very shallow and drying can occur in its eastern and western periphery (Cefas 2007b, 2008b). In contrast, the rest of the voe is much deeper. The inner basin gently slopes away reaching more than 20m at its maximum depth; drying can still occur where this basin meets the head of the voe (Cefas 2007b). The outer basin has steep sides, is 42 m deep at its deepest point and completely open to sea. A shallow sill divides the inner from the outer basins (Cefas 2007b) Busta Voe, Olna Firth and Aith Voe are part of a major inlet on the southern coastline of St Magnus Bay on the west coast of Shetland (Fig.1a). -

The Taing, Bridge End, Burra, Shetland, ZE2

The Taing, Bridge End, Burra, Shetland, ZE2 9LE This two bedroom bungalow is situated in a Offers over £47,000 are invited secluded and picturesque voe of West Burra just a stones through to the shoreline and with stunning Kitchen, Sitting Room, Bathroom and two Double Accommodation sea views. Bedrooms. Refurbishment and repair is required to the dwellinghouse. Planning Permission (ref Extensive grassed garden grounds with Planning 2019/064/PPP) has been obtained to include an External Permission in principle for the erection of a large extension to the rear of the property encompassing Boat Shed. the existing stone built outbuildings. Burra is linked to the mainland by two bridges Highly recommended. Please contact the Seller Viewings affording a rural lifestyle with the amenities of on 01595 696969 to arrange a viewing. Scalloway and Lerwick no more than 20 minutes away. Early entry is available once conveyancing Entry This property presents an ideal opportunity for formalities permit. those looking for a project and county living. EPC Rating Not applicable. Further particulars and Home Report from and all offers to:- Anderson & Goodlad, Solicitors 52 Commercial Street, Lerwick, Shetland, ZE1 0BD T: 01595 692297 F: 01595 692247 E: [email protected] W: www.anderson-goodlad.co.uk Accommodation This property requires extensive renovation and has Planning Permission in principle (“PPP”) (ref. 2019/064/PPP). In its current condition the dwellinghouse has hot and cold water, working toilet, electricity supply, heating and -

Shetland's Wildlife

Shetland’s Wildlife Naturetrek Tour Report 24 June - 2 July 2013 Arctic Skua 2013 Naturetrek Group on St.Ninian's Isle with tombolo behind Northern Fulmars Noup of Noss Report & images compiled by David McAllister Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Shetland’s Wildlife Tour Leader: David McAllister - Naturalist Participants Angela Melamed Robert Pluck Megan Howells Helen Young Nicky Brooks Andy Wainwright Julia Spragg Day 1 Monday 24th June Weather: Calm, clear Between 3 and 5 pm we met David in the Northlink Ferry terminal. On boarding MV Hrossey we settled into our cabins and seats then ate our evening meal so that we could be on deck when the ship sailed. We did some bird-watching as the ship manoeuvred through Aberdeen harbour, and had excellent views of a Grey Seal with fish. Unfortunately the local group of Bottle-nosed Dolphins were not off the pier this year but we did have a brief view of one further out. Day 2 Tuesday 25th June Weather: Bright, sunny in PM The ship passed Fair Isle at about 5am and David and a few of the group were on deck from 5:30 am watching the Fulmars, auks, Gannets and Bonxies (Great Skuas) following the ship. We passed Sumburgh Head and as we came into the Bressay Sound leading to Lerwick met our first Tysties (Black Guillemots), a common sight in Shetland’s harbours. On disembarking we collected the waiting minibus and headed straight for the Sumburgh Hotel where we met Megan, the last member of the group. -

Dowload Lerwick Sale Catalogue

Shetland Livestock Marketing Group In Association with Aberdeen & Northern Marts CATALOGUE OF SHOW AND SALE OF PEDIGREE SHETLAND PONIES To be held at Shetland Rural Centre, Staneyhill, Lerwick, Shetland, ZE1 0NA Tel: 01595 69 6300 Fax: 01595 69 6305 Email: [email protected] SHOW: Thursday 6th October 2011 at 4.30pm SALE: Friday 7th October 2011 at 9.15am PROMPT Best Colt forward in 2010 – “Elangata Ted” Mr E Watt, Aberdeenshire Best Filly forward in 2010 – “Inge of North Booth” Mr A R Priest, Haroldswick IMPORTANT No pony will be sold unless it has been entered into the sale adhering to the SLMG and Auction Mart rules. Buyers are reminded that any ponies they purchase are at their risk at the fall of the hammer. No undertaking of the Auctioneers or their servants to take charge of any lots after the sale or to forward them to their destination shall be held to impose upon the Auctioneers any legal obligation. Whilst every effort is made by SLMG to ensure that the information given regarding pedigree, ownership, detail of colour and date of birth is correct, the responsibility remains with the prospective purchaser to verify these details. Liability for errors and omissions will not be accepted by Shetland Livestock Marketing Group. SHIPPING Buyers must pay for their shipping space at the Auction Mart office at the time of purchase of ponies. The rate for each pony from the Lerwick Mart to Aberdeen will be available from the Auction Mart Office, prior to the sale PASSPORTS Passports and microchips for ponies will be checked at the Sale. -

Statistics for Inhabited Islands

General Register Office for S C O T L A N D information about Scotland’s people Occasional Paper No. 10 Published on 28 November 2003 Scotland’s Census 2001 Statistics for Inhabited Islands This paper present data from the 2001 Census of Population, as well as from earlier Censuses, on the inhabited islands of Scotland. It makes comparisons between individual islands groups and also compares the islands as a whole with Scotland. Contact point: Customer Services Population Statistics Branch General Register Office for Scotland Ladywell House Ladywell Road Edinburgh EH12 7TF Tel: 0131 314 4299 Fax: 0131 314 4696 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.gro-scotland.gov.uk General Register Office for Scotland, © Crown copyright 2003 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3 Commentary............................................................................................................... 3 Demography ........................................................................................................... 3 Households and families......................................................................................... 5 Housing .................................................................................................................. 6 Cultural attributes.................................................................................................... 6 Illness and health................................................................................................... -

Sailing Solo Around the Shetland Islands Summer 2014

Sailing Solo Around the Shetland Islands Summer 2014 “There are no lay-bys up here, only a very hard shoulder” Geoffrey Bowler Royal Forth Yacht Club in “Comma” a 26 foot sloop Wick to Kirkwall, Pierowall, Scalloway, Walls, Brae, Collafirth, Muckle Flugga, Baltasound, Lerwick, Fair Isle, Kirkwall including encounters with the races and overfalls of Lashy Sound, running ahead of gales from France, sensing ghosts in Walls from Teuchter’s Landing, and learning how Swarbacks Minn was the source of Germany’s collapse in 1918 and other truths. Firth of Forth connections in Unst. Heuristic methodology and good luck in Lunning Sound. Encounters with natives of universal helpfulness, friendliness and pragmatism; hostile skua and pelagic trawler in Collafirth; and companionable cetaceans between Fair Isle and North Ronaldsay. From Scalloway, up the West coast of Shetland, past Muckle Flugga, then down the East coast to Fair Isle back to Kirkwall, Comma carried a crew of one. With apologies to Captain Joshua Slocum Comma (CR 2108) is a 7.9 m (26 ft) Westerly Centaur built 1978; with a Beta Marine 20 inboard diesel engine (2014) and 50 litre fuel capacity. She is bilge keeled, draws 0.9 m (3 ft) and displaces 6,700 lbs. Main sail 161 sq ft; now has a furling headsail but originally No.1 Genoa 223 sq ft, No. 1 Jib 133 sq ft. Designer: Laurent Giles. 1 Encouragement received from various seafaring Orcadians and Shetlanders on learning of the plan “The Fair Isle Channel is just a couple of day-sails if you go via Fair Isle.” Mike Cooper, CA HLR and lifeboatman, Orkney “There are no lay-bys up here, only a very hard shoulder”. -

Various Documents

METHOD NOTES 1 Purpose of this CD This CD is provided in order to demonstrate the depth of detail which underlies the development of the maps set out in Chapter 7: The landscape model. The preparation of a comprehensive gazetteer was an essential precursor to drawing up the landscape model but it was not the main aim of the study. By its very nature the gazetteer contains much repetition and chronologically irrelevant material. For this reason only relevant extracts have been included in the main body of the thesis. The full database is presented in this CD as supporting material only, in order to show the workings behind the information used in the thesis, and to set them in context. This electronic document is presented in seven sections as follows: Method Notes Raw data tables Burra Source Maps and Map Notes Houss Source Maps and Map Notes Trondra Source Maps and Map Notes Boundary Maps Large scale map of complex area The source of the contents and the relationship between the sections is explained below. 2 Outline An exercise was carried out to assess and update the known archaeological record for Burra, Houss and Trondra in order to provide a firm foundation for the landscape model which forms a major part of this thesis. A database was created in order to provide an integrated reference point for archaeological sites in the field. The previously known archaeological record for Burra, Houss and Trondra is spread over a number of national and local catalogues and two published surveys. These formed the initial sources of raw data and are described Page 1 METHOD NOTES below.