Nothing but a Shepherd and His Dog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![{PDF EPUB} a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4988/pdf-epub-a-guide-to-prehistoric-and-viking-shetland-by-noel-fojut-a-guide-to-prehistoric-and-viking-shetland-fojut-noel-on-amazon-com-44988.webp)

{PDF EPUB} a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.Com

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut A guide to prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. A guide to prehistoric and Viking Shetland4/5(1)A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland: Fojut, Noel ...https://www.amazon.com/Guide-Prehistoric-Shetland...A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking ShetlandAuthor: Noel FojutFormat: PaperbackVideos of A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland By Noel Fojut bing.com/videosWatch video on YouTube1:07Shetland’s Vikings take part in 'Up Helly Aa' fire festival14K viewsFeb 1, 2017YouTubeAFP News AgencyWatch video1:09Shetland holds Europe's largest Viking--themed fire festival195 viewsDailymotionWatch video on YouTube13:02Jarlshof - prehistoric and Norse settlement near Sumburgh, Shetland1.7K viewsNov 16, 2016YouTubeFarStriderWatch video on YouTube0:58Shetland's overrun by fire and Vikings...again! | BBC Newsbeat884 viewsJan 31, 2018YouTubeBBC NewsbeatWatch video on Mail Online0:56Vikings invade the Shetland Isles to celebrate in 2015Jan 28, 2015Mail OnlineJay AkbarSee more videos of A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland By Noel FojutA Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland - Noel Fojut ...https://books.google.com/books/about/A_guide_to...A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland: Author: Noel Fojut: Edition: 3, illustrated: Publisher: Shetland Times, 1994: ISBN: 0900662913, 9780900662911: Length: 127 pages : Export Citation:... FOJUT, Noel. A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland. ... A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland FOJUT, Noel. 0 ratings by Goodreads. ISBN 10: 0900662913 / ISBN 13: 9780900662911. Published by Shetland Times, 1994, 1994. -

Shetland 2PHF104

shetland 2PHF104 2PHF104 shetland 2PHF114 shetland shetland Colours Balta Oxna Unst Linga 2PHF101 2PHF102 2PHF103 2PHF104 Decors and mixes Bigga Mousa Trondra Foula 2PHF105 2PHF106 2PHF107 2PHF108 supplying your imagination shetland Decors and mixes Muckle Whalsay Yell Vaila 2PHF109 2PHF110 2PHF111 2PHF112 Papa Noss 2PHF113 2PHF114 supplying your imagination shetland Wall mixes *Selected tiles are available in a Matt finish and suitable for walls only. 2PHF116 Lamba* Samphrey* 2PHF115 2PHF116 Bressay* Fetlar* 2PHF117 2PHF118 supplying your imagination Appearance: Patterned Material: Porcelain shetland Usage: Floors and Walls Sizes and finishes 200x200 600x600 800x800 800x1800 1200x1200 8mm 10/20**mm 11mm 11mm 11mm All colours Matt R10 (A+B) Anti Slip R11 (A+B+C) Notes **600x600x20mm is only available in Anti Slip R11 (A+B+C). Decors and mixes are available in size 200x200x8mm in a Matt R10 (A+B) finish. Tiles may display slight variations in print and tone. Please ask for details. Special pieces Square and round top plinths and step treads are available in all colours. For more information contact our sales team. Square and Round Step Treads Top Plinths ISO 10545 results 2 Dimensions and Surface Quality Conforms 10 Moisture Expansion No ratings 3 Water Absorption < 0.5% 12 Frost Resistance Conforms 4 Flexural Strength > 35 N/mm² 13 Chemical Resistance Conforms 6 Deep Abrasion Resistance No ratings 14 Stain Resistance Class 4 2PHF106 8 Linear Thermal Expansion < 9x10-6 °C Slip Resistance Matt R10 (A+B) (DIN 51130-51097) Anti Slip R11 (A+B+C) 9 Thermal Shock Resistance Conforms On request tiles can be tested to PTV BS7976-2. -

Shetland Mainland North (Potentially Vulnerable Area 04/01)

Shetland Mainland North (Potentially Vulnerable Area 04/01) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Shetland Shetland Islands Council Shetland coastal Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impacts flooding of Summary At risk of flooding • <10 residential properties • <10 non-residential properties • £47,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection management warning raising plan/study plans/response study study Maintain flood Strategic Flood Planning Self help Maintenance protection mapping and forecasting policies scheme modelling Shetland Local Plan District Section 2 20 Shetland Mainland North (Potentially Vulnerable Area 04/01) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Shetland Shetland Islands Council Shetland coastal Background This Potentially Vulnerable Area is There are several communities located in the north of Mainland including Voe, Mossbank, Brae and Shetland (shown below). -

Where to Go: Puffin Colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 Puffin Pairs Were Recorded in Ireland at the Time of the Last Census

Where to go: puffin colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 puffin pairs were recorded in Ireland at the time of the last census. We are interested in receiving your photos from ANY colony and the grid references for known puffin locations are given in the table. The largest and most accessible colonies here are Great Skellig and Great Saltee. Start Number Site Access for Pufferazzi Further information Grid of pairs Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Skellig V247607 4,000 worldheritageireland.ie/skellig-michael check local access arrangements Puffin Island - Kerry V336674 3,000 Access more difficult Boat trips available but landing not possible 1,522 Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Saltee X950970 salteeislands.info check local access arrangements Mayo Islands l550938 1,500 Access more difficult Illanmaster F930427 1,355 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Cliffs of Moher, SPA R034913 1,075 check local access arrangements Stags of Broadhaven F840480 1,000 Access more difficult Tory Island and Bloody B878455 894 Access more difficult Foreland Kid Island F785435 370 Access more difficult Little Saltee - Wexford X968994 300 Access more difficult Inishvickillane V208917 170 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Horn Head C005413 150 check local access arrangements Lambay Island O316514 87 Access more difficult Pig Island F880437 85 Access more difficult Inishturk Island L594748 80 Access more difficult Clare Island L652856 25 Access more difficult Beldog Harbour to Kid F785435 21 Access more difficult Island Mayo: North West F483156 7 Access more difficult Islands Ireland’s Eye O285414 4 Access more difficult Howth Head O299389 2 Access more difficult Wicklow Head T344925 1 Access more difficult Where to go: puffin colonies in Inner Hebrides Over 2,000 puffin pairs were recorded in the Inner Hebrides at the time of the last census. -

1972 Report Part 1

SCHOOLS HEBRIDEAN SOCIETY ANNUAL REPORT 1972 Directors of the Schools Hebridean Co.Ltd P.N. RENOLD, B.A. (Chairman) A.J. ABBOTT, M.A.,F.R.G.S. J.C. HUTCHINSON, B.Sc.(Eng) C.M. CHILD, M.A. J.D. LACE A.M. FOWLER G. MACPHERSON, B.Sc.(Eng) J.E.R. HOUGHTON, B.A. R.L.B. MARSHALL, A.C.A. R.A. HOWARD, B.A. P.F. SMITH, LL.B. R. WEATHERLY, B.A. Hon. Advisors to the Society The Rt.Rev. LAUNCELOT FLEMING, M.A.,D.D.,M.S., Dean of Windsor G.L. DAVIES, Esq.,M.A., Trinity College,Dublin S.L. HAMILTON, Esq.,M.B.E. The Schools Hebridean Society is wholly owned by the Schools Hebridean Company Limited, which is registered as a Charity. The Editor of the Report is — ALAN EVISON, Spinney Cottage, Rockfield Road, OXTED, Surrey (Tel.Oxted 2136) OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY DIRECTORS Chairman .............. P.N. Renold, B.A. Deputy Chairman ........ A.J. Abbott, M.A., F.R.G.S. Secretary ............... J.D. Lace Public Relations ....... P.F. Smith, LL.B. Projects .............. A.K. Fowler Financial Director .... R.L.B. Marshall, A.C.A. Treasurer .............. G. Macpherson, B.Sc.(Eng) Membership ............. J.E.R. Houghton, B.A. Non-Executive (Surveying) .. J.C. Hutchinson, B.Sc.(Eng) Non-Executive (Stationery).. C.M. Child, M.A. Non-Executive (Leader) .. R.A. Howard, B.A. Food .................... R. Weatherly, B.A. EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Conference ............. P. Caffery Report .................. A. Evison, B.A. Equipment .............. not yet appointed Travel ................. A. Philips Boats ................... not yet appointed EXPEDITION LEADERS 1972 SHETLAND .............. -

Geopark Shetland

EGN Week 2014 Name of Geopark: Geopark Shetland Dates of geoparks week: 5th – 11th July 2014 Contact person: Robina Barton ([email protected]) This programme may be subject to change. Further events will be added in the coming weeks. Events will be open for booking from 1st May. Unless otherwise stated, all U16s must be accompanied by a responsible adult. Visitors can find an up‐to‐date programme with details of event times and booking information at www.shetlandnaturefestival.co.uk Motto of geoparks week: Discover, Explore, Enjoy!! * Events with a particular geological focus. Category Date Activity / Event 1. Geo & Geo Excursions, museum‐visits, activities at geosites 6th July Eshaness Coast guided walk* Explore the spectacular Eshaness coastline with Geopark Shetland. Once, an ancient volcano spewed out lava and ash to form the rocks of Eshaness. Now, 350 million years later, Atlantic storms have carved them into a spectacular array of cliffs, stacks, geos and caves. Location: Meet at Eshaness car park 7th July Climb Shetland taster session Have a go at sea‐cliff climbing with Shetland climbing club at beginner‐friendly sandstone crags. Minimum age 10 Location: TBC Wet and Wild adventure day See Shetland from a whole new angle through a day of outdoor watersports and exploration, including kayaking and coasteering. Transport provided. Minimum age 10 Location: Meet at St Sunniva St stores 8th July Keen of Hamar guided walk From a distance, the Keen of Hamar may appear to be a barren moonscape, but take a closer look and you’ll discover an array of wild flowers amongst the shattered stones. -

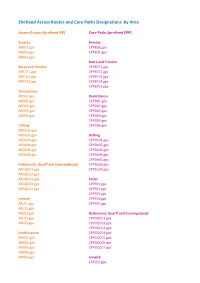

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Codes by Area

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Designations by Area Access Routes (prefixed AR) Core Paths (prefixed CPP) Bressay Bressay ARB01.gpx CPPB01.gpx ARB02.gpx CPPB02.gpx ARB03.gpx Burra and Trondra Burra and Trondra CPPBT01.gpx ARBT01.gpx CPPBT02.gpx ARBT02.gpx CPPBT03.gpx ARBT03.gpx CPPBT04.gpx CPPBT05.gpx Dunrossness ARD01.gpx Dunrossness ARD03.gpx CPPD01.gpx ARD04.gpx CPPD02.gpx ARD05.gpx CPPD03.gpx ARD06.gpx CPPD04.gpx CPPD05.gpx Delting CPPD06.gpx ARDe01.gpx ARDe02.gpx Delting ARDe03.gpx CPPDe01.gpx ARDe04.gpx CPPDe02.gpx ARDe06.gpx CPPDe03.gpx ARDe08.gpx CPPDe04.gpx CPPDe05.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh CPPDe06.gpx ARGQC01.gpx CPPDe07.gpx ARGQC02.gpx ARGQC03.gpx Fetlar ARGQC04.gpx CPPF01.gpx ARGQC05.gpx CPPF02.gpx CPPF03.gpx Lerwick CPPF04.gpx ARL01.gpx CPPF05.gpx ARL02.gpx ARL03.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh ARL04.gpx CPPGQC01.gpx ARL05.gpx CPPGQC02.gpx CPPGQC03.gpx Northmavine CPPGQC04.gpx ARN01.gpx CPPGQC05.gpx ARN02.gpx CPPGQC06.gpx ARN03.gpx CPPGQC07.gpx ARN04.gpx ARN05.gpx Lerwick CPPL01.gpx Nesting and Lunnasting CPPL02.gpx ARNL01.gpx CPPL03.gpx ARNL02.gpx CPPL04.gpx ARNL03.gpx CPPL05.gpx CPPL06.gpx Sandwick ARS01.gpx Northmavine ARS02.gpx CPPN01.gpx ARS03.gpx CPPN02.gpx ARS04.gpx CPPN03.gpx CPPN04.gpx Sandsting and Aithsting CPPN05.gpx ARSA04.gpx CPPN06.gpx ARSA05.gpx CPPN07.gpx ARSA07.gpx CPPN08.gpx ARSA10.gpx CPPN09.gpx CPPN10.gpx Scalloway CPPN11.gpx ARSC01.gpx CPPN12.gpx ARSC02.gpx CPPN13.gpx Skerries Nesting and Lunnasting ARSK01.gpx CPPNL01.gpx CPPNL03.gpx Tingwall, Whiteness and Weisdale CPPNL04.gpx -

Island Sheep Catalogue

Aberdeen & Northern Marts A member of ANM GROUP LTD. THAINSTONE CENTRE, INVERURIE TELEPHONE : 01467 623710 WEEKLY SALE OF ISLAND CONSIGNMENTS FRIDAY 29th SEPTEMBER 2017 SALE ARRANGEMENTS Sale Ring No 3 Island Consignments at 1.00 pm TERMS OF SALE - CASH PASS PEN NO CONSIGNOR FA NO. 546-547 50 Setter Bressay Shetland 007543 548-549 50 Burland Trondra Scalloway Shetland 550-551 38 12 Sunnyside Mid Yell Yell Shetland 552-554 76 South Scord Muckle Roe Brae Shetland 555 14 Ewe South Scord Muckle Roe Brae Shetland 555 4 Ewe Daburn Muckle Roe Brae Shetland 556 20 Rodahamar Muckle Roe Brae Shetland 557 24 Kilkahoull Muckle Roe Brae Shetland 557 6 Ewe Kilkahoull Muckle Roe Brae Shetland 558 20 Nia-roo Gott Shetland 003170 559 12 Nia-roo Gott Shetland 003170 560-564 114 The Barn, New Gord Westing Unst Shetland 565 13 Ewe The Barn, New Gord Westing Unst Shetland 568 20 Ewe Vendeshoul Westing Uyeasound Unst Shetland 568 1 Vendeshoul Westing Uyeasound Unst Shetland 569 26 Seafield House Lerwick Shetland 570-571 36 Trebister Gulberwick Lerwick Shetland 572-573 46 Hellister Weisdale Lerwick Shetland 574 29 Clovelly Bixter Lerwick Shetland 575 9 Clovelly Bixter Lerwick Shetland 595 7 Clovelly Bixter Lerwick Shetland 576-581 124 Isbister North Roe Shetland 582 16 Ewe Isbister North Roe Shetland Lambs 583 22 Ewe Uradell Eshaness Shetland 583 1 Gmr Uradell Eshaness Shetland 584 24 Uradell Eshaness Shetland 585 35 Snarraness House Bridge of Walls Shetland 014179 586 7 8 Marthastoon Aith Bixter Shetland 586 3 Ewe 8 Marthastoon Aith Bixter Shetland 587 7 Ewe -

Origins of Fair Isle Knitting

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America Spring 2004 Traveling Stitches: Origins of Fair Isle Knitting Deborah Pulliam [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Pulliam, Deborah, "Traveling Stitches: Origins of Fair Isle Knitting" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 467. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/467 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Traveling Stitches: Origins of Fair Isle Knitting Deborah Pulliam Box 667, Castine ME 04421 207 326 9582 [email protected] The tradition of Fair Isle knitting seems to have been emerged too well developed to have actually started in the islands north of Scotland. This paper suggests a source in the Baltic region of Eastern Europe. Like much of the “history” of knitting, much published information on the history of Fair Isle-type knitting is folklore. The long-standing story is that a ship, El Gran Grifon, from the Spanish Armada, was wrecked on Fair Isle in 1588. The 17 households on the island took the sailors in. That much is true, and documented. The knitting story is that, in return, the Spaniards taught the islanders the brightly colored patterned knitting now known as Fair Isle. Not surprisingly, there appears to have been no multi-colored knitting tradition in Spain in the sixteenth century. -

Scottish Sanitary Survey Programme

Scottish Sanitary Survey Programme Sanitary Survey Report Production Area: South Uyea SIN : SI 263 454 08 April 2012 Report Distribution – South Uyea Date Name Agency Linda Galbraith Scottish Government Morag MacKenzie SEPA Douglas Sinclair SEPA Fiona Garner Scottish Water Alex Adrian Crown Estate Dawn Manson Shetland Islands Council Sean Williamson NAFC Marine Council David Niven Harvester Chris Webb Northern Isles Salmon South Uyea Sanitary Survey Report Final V1.0 i Table of Contents I. Executive Summary .................................................................................. 1 II. Sampling Plan ........................................................................................... 3 III. Report .................................................................................................... 4 1. General Description .................................................................................. 4 2. Fishery ...................................................................................................... 5 3. Human Population .................................................................................... 6 4. Sewage Discharges .................................................................................. 8 5. Geology and Soils ................................................................................... 11 6. Land Cover ............................................................................................. 12 7. Farm Animals ......................................................................................... -

List of Shetland Islands' Contributors Being Sought by Kist O Riches

List of Shetland Islands’ Contributors being Sought by Kist o Riches If you have information about any of the people listed or their next-of-kin, please e-mail Fraser McRobert at [email protected] or call him on 01471 888603. Many thanks! Information about Contributors Year Recorded 1. Mrs Robertson from Burravoe in Yell who was recorded reciting riddles. She was recorded along with John 1954 Robertson, who may have been her husband. 2. John Robertson from Fetlar whose nickname was 'Jackson' as he always used to play the tune 'Jackson's Jig'. 1959 He had a wife called Annie and a daughter, Aileen, who married one of the Hughsons from Fetlar. 3. Mr Gray who sounded quite elderly at the time of recording. He talks about fiddle tunes and gives information 1960 about weddings. He may be the father of Gibbie Gray 4. Mr Halcro who was recorded in Sandwick. He has a local accent and tells a local story about Cumlewick 1960 5. Peggy Johnson, who is singing the ‘Fetlar Cradle Song’ in one of her recordings. 1960 6. Willie Pottinger, who was a fiddle player. 1960 7. James Stenness from the Shetland Mainland. He was born in 1880 and worked as a beach boy in Stenness in 1960 1895. Although Stenness is given as his surname it may be his place of origin 8. Trying to trace all members of the Shetland Folk Club Traditional Band. All of them were fiddlers apart from 1960 Billy Kay on piano. Members already identified are Tom Anderson, Willie Hunter Snr, Peter Fraser, Larry Peterson and Willie Anderson 9. -

TOUCHDOWN the OBAN AIRPORT Newsletter

TOUCHDOWN The OBAN AIRPORT Newsletter Issue 4 Jan-Mar 2013 Latest From OBAN AIRPORT FEATURES Latest From Oban Airport Welcome to the first Newsletter of 2013, On behalf of everyone at the Airport, we hope you all had a good Christmas and wish you all the best for the New Year. The last few weeks have seen a great deal of change INSIDE THIS ISSUE in weather with a huge amount of rain all around the country and although the West Coast has come through it fairly well, our thoughts go Biggest Aircraft out to all those who were badly affected. As I write this, the weather is fairly pleasant but the temperatures are starting to come down a bit. LE JOG Event The Islander Aircraft—A The change in temperatures have meant that most of us have been brief history subjected to the usual winter colds and flu. Ah well, its back to normal now and we are looking forward to the challenges that this year brings. Coll and it’s Airfields—A Last December (14th) the Airport was featured on Landward, BBC2 history of aviation on the (Scotland) , which displayed the scheduled services and yours truly. Isle of Coll However I was still sporting my ‘Movember’ look and was interviewed Local Businesses with Mexican-type facial hair. The show was extremely good and demonstrated how good the Air Service is to the Islands. Robert Burns In this Issue, we will be looking at some of the future developments Scottish Island Aerodromes around the area and what impact it may have on the Airport.