Nsw National Parks & Beekeeping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vegetation on Fraser Island

Vegetation On Fraser Island Imagine towering pines, rainforest trees with three metre girths, rare and ancient giant ferns, eucalypt forests with their characteristic pendulous leaves, lemon-scented swamp vegetation and dwarfed heathland shrubs covered in a profusion of flowers. Now imagine them all growing on an island of sand. Two of Fraser Island’s unique features are its diversity of vegetation and its ability to sustain this vegetation in sand, a soil that is notoriously low in nutrients essential to plant growth. Plants growing on the dunes can obtain their nutrients (other than nitrogen) from only two sources - rain and sand. Sand is coated with mineral compounds such as iron and aluminium oxides. Near the shore the air contains nutrients from sea spray which are deposited on the sand. In a symbiotic relationship, fungi in the sand make these nutrients available to the plants. These in turn supply various organic compounds to the fungi which, having no chlorophyll cannot synthesise for themselves. Colonising plants, such as spinifex, grow in this nutrient poor soil and play an integral role in the development of nutrients in the sand. Once these early colonisers have added much needed nutrients to the soil, successive plant communities that are also adapted to low nutrient conditions, can establish themselves. She-oaks ( Allocasuarina and Casuarina spp.) can be found on the sand dunes of the eastern beach facing the wind and salt spray. These hardy trees are a familiar sight throughout the island with their thin, drooping branchlets and hard, woody cones. She-oaks are known as nitrogen fixers and add precious nutrients to the soil. -

NSW Budget- $108 Million Bus Boost

Andrew Constance Minister for Transport and Infrastructure Gladys Berejiklian Treasurer Minister for Industrial Relations MEDIA RELEASE Tuesday, 14 June 2016 NSW BUDGET: $108 MILLION BUS BOOST Double decker buses will serve some of Sydney’s busiest routes, and around 3,800 extra weekly services will be added as part of a $108 million investment in new buses in the 2016- 17 NSW Budget, Minister for Transport and Infrastructure Andrew Constance and Treasurer Gladys Berejiklian announced today. The 80 seat double deckers can carry 65 per cent more capacity than normal size buses, and will be used on key corridors including the busy Rouse Hill-City service (route 607X), between Blacktown and Macquarie Park (route 611), and for the first time, the Liverpool- Parramatta Transitway (route T80). “Thousands of Sydneysiders rely on bus travel every day to get from A to B and we know demand for services is continually increasing, particularly in growth centres in the North West and South West, as well as in inner city areas like Green Square,” Mr Constance said. “This is all about staying ahead of the curve to ensure customers have sufficient levels of service well into the future. “Since coming to office, the NSW Government has delivered more than 15,800 extra weekly public transport services for customers and today’s announcement is further proof that we’re committed to putting on even more where and when they’re needed most.” Ms Berejiklian said the Government would continue to fund more services and infrastructure in the upcoming Budget. “These double decker buses have allowed us to deliver good customer outcomes and we are pleased to be rolling out more of them across Sydney,” the Treasurer said. -

Nsw Apiarists' Association Inc

NSW APIARISTS’ ASSOCIATION INC. Bees and beekeepers are essential for Australia Submission to the Australian Senate Inquiry into: The future of the beekeeping and pollination service industries in Australia To the Senate Standing Committee Please find here the submission from the New South Wales Apiarists’ Association (NSWAA) to the Senate Inquiry: Future of the beekeeping and pollination service industries in Australia. NSWAA is the state peak body for commercial beekeepers, and the Association represents its members to all levels of government. There are currently around 3,000 registered beekeepers in NSW, which represents about 45 per cent of Australia’s beekeeping industry. NSW commercial beekeepers manage over 140,000 hives, but these numbers are declining at an alarming rate – 30% since 2006 – and this is reflected nationally. While the beekeeping industry is a relatively small one, it plays a highly significant role within the agricultural sector of NSW, and more broadly across Australia. Beekeeping is essential not just for honey and other hive products, but also for pollination of the food crops that feed us and our livestock. Most importantly, our industry stands between Australia and a looming food security crisis. However, Australian commercial beekeepers can’t stave off this crisis without assistance. There are three significant threats to our industry, which endanger the vital pollination services provided by beekeepers. These are access to floral resources, pests and diseases, and increasing pressures on the industry’s economic viability. We address these issues in detail below. We would like to thank the Senate Standing Committees on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport for making available this opportunity to provide you with this submission on the importance of beekeeping and pollination services in Australia. -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Chemical Composition and Insecticidal Activities of Essential Oils of Myrtaceae Against Tribolium Castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae)

Pol. J. Environ. Stud. Vol. 26, No. 4 (2017), 1653-1662 DOI: 10.15244/pjoes/73800 Original Research Chemical Composition and Insecticidal Activities of Essential Oils of Myrtaceae against Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) Saima Siddique1*, Zahida Parveen3, Firdaus-e-Bareen2, Abida Butt4, Muhammad Nawaz Chaudhary1, Muhammad Akram5 1College of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of the Punjab, 54890-Lahore, Pakistan 2Department of Botany, University of Punjab, Lahore-54890, Pakistan 3Applied Chemistry Research Centre, PCSIR Laboratories Complex, Lahore-54600, Pakistan 4Department of Zoology, University of the Punjab, 54890-Lahore, Pakistan 5Medicinal Botanic Centre, PCSIR Laboratories Complex, Peshawar-25000, Pakistan Received: 22 April 2017 Accepted: 15 May 2017 Abstract The present study was designed to determine chemical composition of essential oils extracted from different species of the Myrtaceae family and to evaluate their insecticidal activities against Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). The essential oils of 10 species were extracted by hydrodistillation and analyzed by a gas chromatography-flame ionization detector (GC-FID) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The main component of Eucalyptus crebra, E. microtheca, E. rudis and Melaleuca quinquenervia essential oils was 1,8-cineole (31.6-49.7%). E. melanophloia and E. tereticornis contained p-cymene (41.8-58.1%) as a major component, while Eucalyptus kitsoniana and E. pruinosa essential oils were dominated by α-pinene (25.8-31.4%). Eugenol methyl ether was identified as a major component in M. bracteata essential oil (82.3%). α-Pinene (31.4%) was the main component in the C. viminalis essential oil. Essential oils of all selected plant species showed good insecticidal activities against T. -

Eucalyptus Dumosa White Mallee Classification Eucalyptus | Symphyomyrtus | Dumaria | Rufispermae Nomenclature

Euclid - Online edition Eucalyptus dumosa White mallee Classification Eucalyptus | Symphyomyrtus | Dumaria | Rufispermae Nomenclature Eucalyptus dumosa A.Cunn. ex J.Oxley, J. Two Exped. Int. New South Wales 63 (1820). Eucalyptus incrassata var. dumosa (A.Cunn. ex J.Oxley) Maiden, Crit. Revis. Eucalyptus 1: 96 (1904). T: Euryalean Scurb, between 33°and 34°S, and 146° and 147°E, NSW, 23 May 1817, A.Cunningham 206; iso: BM, CANB, E, K. Eucalyptus lamprocarpa F.Muell. ex Miq., Ned. Kruidk. Arch. 4: 129 (1856). T: not designated. Eucalyptus muelleri Miq., op.cit. 130. T: 'Madam Pepper-wealth ad fl. Murray'; F.Mueller. Description Mallee to 10 m tall. Forming a lignotuber. Bark usually rough on lower part of stems, grey or grey-brown, flaky or box-type; smooth bark white, yellow, grey, brown or pink-grey, shedding in ribbons from the upper stems and branches, rarely powdery. Branchlets with oil glands in the pith. Juvenile growth (coppice or wild seedling to 50 cm tall): stem rounded in cross-section; juvenile leaves always petiolate, opposite for 2 or 3 pairs then alternate, petiolate, ovate to broadly lanceolate, 5.5–14 cm long, 2.2–7 cm wide, blue-green or grey-green. Adult leaves alternate, petiole 0.8–2.5 cm long; blade lanceolate to falcate, 4.8–12 cm long, 0.8–2.5 cm wide, base tapering to petiole, concolorous, usually dull, blue-green to grey-green or almost grey, or maturing glossy green, side-veins at an acute or wider angle to midrib, moderately to very densely reticulate but with veinlets erose, intramarginal vein parallel to and just within margin, oil glands numerous mostly intersectional or obscure. -

Gum Trees Talk Notes

Australian Plants Society NORTH SHORE GROUP Eucalyptus, Angophora, Corymbia FAMILY MYRTACEAE GUM TREES OF THE KU-RING-GAI WILDFLOWER GARDEN Did you know that: • The fossil evidence for the first known Gum Tree was from the Tertiary 35-40 million years ago. • Myrtaceae is a very large family of over 140 genera and 3000 species of evergreen trees and shrubs. • There are over 900 species of Gum Trees in the Family Myrtaceae in Australia. • In the KWG, the Gum Trees are represented in the 3 genera: Eucalyptus, Angophora & Corymbia. • The name Eucalyptus is derived from the Greek eu = well and kalyptos = covered. BRIEF HISTORY E. obliqua The 18th &19th centuries were periods of extensive land exploration in Australia. Enormous numbers of specimens of native flora were collected and ended up in England. The first recorded scientific collection of Australian flora was made by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, during Sir James Cook’s 1st voyage to Botany Bay in April 1770. From 1800-1810, George Caley collected widely in N.S.W with exceptional skill and knowledge in his observations, superb preservation of plant specimens, extensive records and fluent expression in written records. It is a great pity that his findings were not published and he didn’t receive the recognition he deserved. The identification and classification of the Australian genus Eucalyptus began in 1788 when the French botanist Charles L’Heritier de Brutelle named a specimen in the British Museum London, Eucalyptus obliqua. This specimen was collected by botanist David Nelson on Captain Cook’s ill- fated third expedition in 1777 to Adventure Bay on Tasmania’s Bruny Is. -

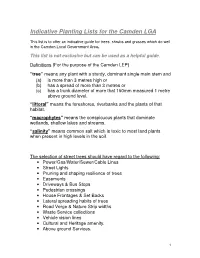

Indicative Planting Lists for the Camden LGA

Indicative Planting Lists for the Camden LGA This list is to offer an indicative guide for trees, shrubs and grasses which do well in the Camden Local Government Area . This list is not exclusive but can be used as a helpful guide . Definitions (For the purpose of the Camden LEP) “tree” means any plant with a sturdy, dominant single main stem and (a) is more than 3 metres high or (b) has a spread of more than 3 metres or (c) has a trunk diameter of more that 150mm measured 1 metre above ground level. “littoral” means the foreshores, riverbanks and the plants of that habitat. “macrophytes” means the conspicuous plants that dominate wetlands, shallow lakes and streams. “salinity” means common salt which is toxic to most land plants when present in high levels in the soil. The selection of street trees should have regard to the following: • Power/Gas/Water/Sewer/Cable Lines • Street Lights • Pruning and shaping resilience of trees • Easements • Driveways & Bus Stops • Pedestrian crossings • House Frontages & Set Backs • Lateral spreading habits of trees • Road Verge & Nature Strip widths • Waste Service collections • Vehicle vision lines • Cultural and Heritage amenity. • Above ground Services. 1 Indicative Nature Strip - Street Tree selection Species Name Common Name Height Width Native Acer palmatum ‘Senkaki’ Coral Bark Maple 4m 3m Acer rubrum ‘October Red Maple 9m 7m Glory’ Acmena smithii ‘Red Red Head Acmena 6m 2m yes Head’ Agonis flexuosa Willow Myrtle 8m 4m yes Angophora costata Dwarf Dwarf Angophora 4m 2m yes ‘Darni’ costata ‘Darni’ -

Inquiry Into Beekeeping in Urban Areas

THE GOVERNMENT OF NEW SOUTH WALES INQUIRY INTO BEEKEEPING IN URBAN AREAS REPORT AUGUST 2000 Inquiry Into Bee Keeping Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. ORIGIN OF THE INQUIRY ......................................................................................................................1 2. TERMS OF REFERENCE OF THE INQUIRY ........................................................................................1 3. CORONIAL FINDING.................................................................................................................................1 4. CONDUCT OF THE JOINT MINISTERIAL INQUIRY.........................................................................2 4.1 CONSULTATION ON THE INQUIRY .............................................................................................2 4.2 SUBMISSIONS TO THE INQUIRY ..................................................................................................2 5. IDENTIFY THE EXTENT TO WHICH BEES ARE KEPT IN URBAN AREAS OF NEW SOUTH WALES (TOR 1). ..........................................................................................................................................3 5.1 BEEKEEPING IN AUSTRALIA ........................................................................................................3 5.1.1 Swarms ..........................................................................................................................................4 5.1.2 Swarm Control..............................................................................................................................4 -

Five-Year Survival and Growth of Farm Forestry Plantings of Native Trees and Radiata Pine in Pasture Affected by Position in the Landscape

CSIRO PUBLISHING Animal Production Science, 2013, 53, 817–826 http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/AN11247 Five-year survival and growth of farm forestry plantings of native trees and radiata pine in pasture affected by position in the landscape Nick Reid A,C, Jackie Reid B, Justin Hoad A, Stuart Green A, Greg Chamberlain A and J. M. Scott A ASchool of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia. BSchool of Science and Technology, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Woodlots ranging in area from 0.18 to 0.5 ha were established within the Cicerone Project farmlet trial on the Northern Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia, due to a lack of physical protection in most paddocks across the farmlets. Two percent of each farmlet was planted to trees to examine the commercial and environmental potential of seven species to provide shade and shelter for livestock, increase biodiversity or contribute to cash flow through farm forestry diversification. Eucalyptus caliginosa (timber), E. nitens (timber, pulp wood), E. radiata (essential oil) and Pinus radiata (timber) were planted in four upslope plots (1059–1062 m a.s.l.) in different paddocks. Casuarina cunninghamiana (timber, shelter), E. acaciiformis (shade, shelter and biodiversity), E. dalrympleana (timber, biodiversity), E. nitens (timber, pulp wood), E. radiata (essential oil) and P. radiata (timber) were planted in four low-lying plots (1046–1050 m a.s.l.) in separate paddocks, 400–1200 m distant. The pines and natives were planted in August and October 2003, respectively, into a well prepared, weed-free, mounded, planting bed. -

Post-Fire Recovery of Woody Plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion

Post-fire recovery of woody plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion Peter J. ClarkeA, Kirsten J. E. Knox, Monica L. Campbell and Lachlan M. Copeland Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, AUSTRALIA. ACorresponding author; email: [email protected] Abstract: The resprouting response of plant species to fire is a key life history trait that has profound effects on post-fire population dynamics and community composition. This study documents the post-fire response (resprouting and maturation times) of woody species in six contrasting formations in the New England Tableland Bioregion of eastern Australia. Rainforest had the highest proportion of resprouting woody taxa and rocky outcrops had the lowest. Surprisingly, no significant difference in the median maturation length was found among habitats, but the communities varied in the range of maturation times. Within these communities, seedlings of species killed by fire, mature faster than seedlings of species that resprout. The slowest maturing species were those that have canopy held seed banks and were killed by fire, and these were used as indicator species to examine fire immaturity risk. Finally, we examine whether current fire management immaturity thresholds appear to be appropriate for these communities and find they need to be amended. Cunninghamia (2009) 11(2): 221–239 Introduction Maturation times of new recruits for those plants killed by fire is also a critical biological variable in the context of fire Fire is a pervasive ecological factor that influences the regimes because this time sets the lower limit for fire intervals evolution, distribution and abundance of woody plants that can cause local population decline or extirpation (Keith (Whelan 1995; Bond & van Wilgen 1996; Bradstock et al. -

New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus Nova-Anglica) Grassy

Advice to the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee on an Amendment to the List of Threatened Ecological Communities under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) 1. Name of the ecological community New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus nova-anglica) Grassy Woodlands This advice follows the assessment of two public nominations to list the ‘New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus nova-anglica) Woodlands on Sediment on the Northern Tablelands’ and the ‘New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus nova-anglica) Woodlands on Basalt on the Northern Tablelands’ as threatened ecological communities under the EPBC Act. The Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) recommends that the national ecological community be renamed New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus nova-anglica) Grassy Woodlands. The name reflects the fact that the definition of the ecological community has been expanded to include all grassy woodlands dominated or co-dominated by Eucalyptus nova-anglica (New England Peppermint), in New South Wales and Queensland. Also the occurrence of the ecological community extends beyond the New England Tableland Bioregion, into adjacent areas of the New South Wales North Coast and the Nandewar bioregions. Part of the national ecological community is listed as endangered in New South Wales, as ‘New England Peppermint (Eucalyptus nova-anglica) Woodland on Basalts and Sediments in the New England Tableland Bioregion’ (NSW Scientific Committee, 2003); and, as an endangered Regional Ecosystem in Queensland ‘RE 13.3.2 Eucalyptus nova-anglica ± E. dalrympleana subsp. heptantha open-forest or woodland’ (Qld Herbarium, 2009). 2. Public Consultation A technical workshop with experts on the ecological community was held in 2005.