Twenty Questions for Noël Arnaud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eunoia: the Good Bök - Times Online 21/11/08 5:14 PM

Eunoia: The good Bök - Times Online 21/11/08 5:14 PM Credit Munch Get 20% off your bill at Pizza Express Britain's still paying a heavy price for misjudgments in the inter-war years Libby Purves NEWS COMMENT BUSINESS MONEY SPORT LIFE & STYLE TRAVEL DRIVING ARTS & ENTS VIDEO ARCHIVE OUR PAPERS FILM MUSIC STAGE VISUAL ARTS TV & RADIO WHAT'S ON BOOKS THE TLS GAMES & PUZZLES Where am I? Home Arts & Entertainment Books Times Online From The Times MY PROFILE SHOP JOBS PROPERTY CLASSIFIEDS November 14, 2008 MOST READ MOST COMMENTED MOST CURIOUS Eunoia: The good Bök TODAY Horror as teenager commits suicide live... Giles Whittell meets Christian Bök, the Canadian writer behind Briton found guilty of throwing lover off... Eunoia, the univocal bestseller Business big shot: Arianna Huffington,... Somali pirates seize ninth vessel in 12 days EXPLORE BOOKS BOOK EXTRACTS BOOK REVIEWS BOOKS GROUP AUDIO BOOKS TIMES RECOMMENDS And the Hippos were Boiled in their Tanks by William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac Sci-fi: Little Brother by Cory DURING THE SEVEN YEARS it took Christian Bök to write Doctorow and The Quiet War Eunoia he would often read to audiences from his work in by Paul McAuley progress. He preferred not to tell them what was coming so that he could see the look on their faces when they realised what was happening. REVIEW “It would suddenly start dawning on people that I was performing this very athletic and acrobatic feat,” he says. “You could see the FOCUS ZONE light bulbs going on.” Listeners' first instinct would be to “wait for the moment of failure, Social Entrepreneurs: to see where I had screwed up. -

Guide Pédagogique 08 EN

THE LIPOGRAM Fin de soirée , de Tristan Bastit Info Sheet Jeux de mots: 7th Blue Metropolis Lipogram Contest _______________________________________________ By EVE PARISEAU What is a lipogram? Lipograms are literary word games in which the writer intentionally avoids using one or more letters of the alphabet. In 1969, the great French writer Georges Perec wrote an entire novel, La Disparition , without using the letter e. Up for the challenge? A Brief Description of the Activity SECOND ACTIVITY Working with lipograms provides an excellent LIPOGRAM WORKSHOP opportunity for integrating creative writing and word play into classroom work. Lipograms, with the formal Activity Description constraints they place on which words can be used, Students search—with or without a dictionary, alone or encourage students to explore the limits of language. in groups—lipogrammatic words (words without a certain vowel) having to do with a defined subject, and Educational Goals which can replace other words. Since this is the second The proposed activities are aimed at meeting goals for exercise, the teacher may want to choose vowels less writing, reading and oral expression in poetry and constraining than the “e”. narrative. The students’ grammatical abilities, spelling and syntax, and their lexical and semantic development, Educational Goals will be put to the test, as well as their ability to work with Develop the students’ lexical skills humour. The challenges of the lipogram have a natural Develop lexical fields teaching effect. Familiarize students with lipograms What’s Needed Time Required The understanding of a few basic concepts is required A half-session for the student to participate. -

Christian Bök (1966 — ) Is a Professor at the University of Calgary, and He Is the Author of Two Books of Poetry

Parliamentary Poet Laureate POETRY CONNECTION: LINK UP WITH CANADIAN POETRY Christian Bök (1966 — ) is a professor at the University of Calgary, and he is the author of two books of poetry. Crystallography (Coach House, 1994) has been nominated for the Gerald Lampert Award for Best Poetic Debut, and Eunoia (Coach House, 2001) has won the 2002 Griffin Poetry Prize, becoming a bestseller in Canada and the UK. Eunoia consists of five chapters (each of which tells a story, using words that contain only one of the five vowels). Bök has also published a book of critical writing, entitled ‘Pataphysics: The Poetics of an Imaginary Science (Northwestern University Press, 2001). Bök has created artificial languages for two TV shows: Gene Roddenberry’s Earth: Final Conflict and Peter Benchley’s Amazon. He has also exhibited artworks in galleries around the world. Poem for discussion: “The Perfect Malware” is a selection from an ongoing project, entitled The Xenotext, a transgenic artwork that Bök has been creating for the last 11 years at a cost of $120,000. Bök has written two poems that mutually encode each another (e.g., the word “lyre” in one poem translates to “rely” in the other, with L assigned to R and E assigned to Y). Bök has encoded the first poem as a sequence of DNA implanted into a bacterium. The lifeform then “reads” this poem, as part of its normal biological processes, and then the lifeform “writes” the second poem, encoding it into a sequence of amino acids that make up a protein. Bök is quite literally writing a living poem. -

A Moma Sestina

CutBank Volume 1 Issue 77 CutBank 77 Article 38 Fall 2012 Eunoia Eye to Eye: A MoMa Sestina Desmond Kon Zhicheng-Mingde Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank Part of the Creative Writing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Zhicheng-Mingde, Desmond Kon (2012) "Eunoia Eye to Eye: A MoMa Sestina," CutBank: Vol. 1 : Iss. 77 , Article 38. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank/vol1/iss77/38 This Poetry is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in CutBank by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DESMOND KON Z H I C H E N G-M I N G D E EUNOIA EYE TO EYE: A MOMA SESTINA The wheelmen, when wet, wrest the wheel. — Christian Bok Eunoia, this is not a new aesthetic or epistemology about beauty, what ends undergird Wittgenstein’s wit, pronouncements of logic, any subject under Novalis and this noonday sky, of the theory of symbolism trumping names, of the theory of types being categorical squares, pointy corners overlapping, inward spiral into an nth number of trapezoids colliding, more intoned inside, artifice as objects seen sub specie aeternitatis, happy despite eulogies and euphemisms, or toasting revisioned lives, what possibility got shored up and unraveled, red mountain of origami tigers dissolved in acid rain, timed to end November, feast days from St. Martin’s to the long road home, -

On Writing Lipograms

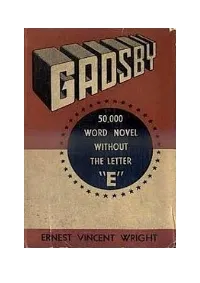

33 ON WRITING LIPOGRAMS ROBERT CASS KELLER e changed Why is it that writers usually OITlit E, the ITlost COITlITlOn letter in word? English text, when creating a literary lipograITl? I believe that this and LIER tendency has been reinforced by the existence of the only book-length English-language lipograITl, Ernest V. Wright's E-less novel, Gadsby (Wetzel, Los Angeles, 1939). In fact, its influence ITlay have extend ination ed even to France. OuLiPo ITleITlber Georges Perec constructed La ,ilarly, Disparation (Denoel, Paris, 1969) without using the letter E; SOITle of the book's reviewers did not even realize that it was a lipograITl! rage Obviously, oITlitting any other letter should ITlake the lipograITlITla tic task easier. To restore balance, I propose that a lipograITl ought twice as to be constructed oITlitting as ITlany letters of the alphabet as possible. cry. In Throwing away the rarest letters first, how ITlany can be eliITlinated Answers before the task of writing with the reITlainder is cOITlparable to a ITlis sing E? A first answer to this question can be given by' reITloving let ters which collectively have the frequency of E in English text -- the eleven letters ZQJXKVBYGWP. When constructing a lipograITl, short words are ITlore valuable ,ate than long ones, for it is likely that ITlost long words will be eliITlinated ard no ITlatter what letters are thrown away. If a given alphabetic letter is ITlore prevalent in short words than long one s, this letter ought not heavily to be reITloved. For exaITlple, the rather rare letter W is concentrated iITl in several COITlITlon short words, such as WAS, WITH, WHERE, WERE, :lal WHEN and WILL; F occurs in the very COITlITlon OF, FOR and FROM. -

Serious Play: Formal Innovation and Politics in French Literature from the 1950S to the Present

Serious Play: Formal Innovation and Politics in French Literature from the 1950s to the Present by Aubrey Ann Gabel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Lucey, Chair Professor Debarati Sanyal Professor C.D. Blanton Professor Mairi McLaughlin Summer 2017 Abstract Serious Play: Formal Innovation and Politics in French Literature from the 1950s to the Present By Aubrey Ann Gabel Doctor of Philosophy in French University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Lucey, Chair Serious Play: Formal Innovation and Politics in French literature from the 1950s to the present investigates how 20th- and 21st-century French authors play with literary form as a means of engaging with contemporary history and politics. Authors like Georges Perec, Monique Wittig, and Jacques Jouet often treat the practice of writing like a game with fixed rules, imposing constraints on when, where, or how they write. They play with literary form by eliminating letters and pronouns; by using only certain genders, or by writing in specific times and spaces. While such alterations of the French language may appear strange or even trivial, by experimenting with new language systems, these authors probe into how political subjects—both individual and collective—are formed in language. The meticulous way in which they approach form challenges unspoken assumptions about which cultural practices are granted political authority and by whom. This investigation is grounded in specific historical circumstances: the student worker- strike of May ’68 and the Algerian War, the rise of and competition between early feminist collectives, and the failure of communism and the rise of the right-wing extremism in 21st-century France. -

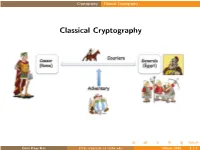

` `%%%`#`&12 `__~~~Classical Cryptography

Cryptography Classical Cryptography Classical Cryptography C¸etin Kaya Ko¸c http://koclab.cs.ucsb.edu Winter 2016 1 / 1 Cryptography Classical Cryptography Shift Cipher Input/output: {a, b,..., z} with encoding {0, 1,..., 25} a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 p q r s t u v w x y z 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Encryption function: Ek (x)= x + k (mod 26) Decryption function: Dk (y)= y − k (mod 26) The encryption or decryption key: k ∈ {0, 1, 2,..., 25} Key space size: 26 (or 25, if you do not count k = 0) Caesar cipher: Shift cipher with a constant encryption key k = 3 C¸etin Kaya Ko¸c http://koclab.cs.ucsb.edu Winter 2016 2 / 1 Cryptography Classical Cryptography Shift Cipher For k = 15, hello is encrypted as wtaad since E15(h)= E15(7) = 7 + 15 = 22 (mod 26) → w E15(e)= E15(4) = 4 + 15 = 19 (mod 26) → t E15(l)= E15(11) = 11 + 15 = 26 = 0 (mod 26) → a E15(o)= E15(14) = 14 + 15 = 29 = 3 (mod 26) → d For k = 12, eqqw is decrypted as seek since D12(e)= D12(4) = 4 − 12 = −8 = 18 (mod 26) → s D12(q)= D12(16) = 16 − 12 = 4 (mod 26) → e D12(w)= D12(22) = 22 − 12 = 10 (mod 26) → k C¸etin Kaya Ko¸c http://koclab.cs.ucsb.edu Winter 2016 3 / 1 Cryptography Classical Cryptography Cryptanalysis of Shift Cipher Ciphertext only (CO) Exhaustive key search: a paragraph of ciphertext (in order to avoid ambiguity) Frequency analysis: a paragraph of ciphertext (in order to get statistically reliable frequency count) Known plaintext (KP): a single plaintext/ciphertext pair Chosen plaintext (CP): a single plaintext/ciphertext -

The Meaning Revealed at the Nth Degree in Christian Bök's Eunoia

The Meaning Revealed at the Nth Degree in Christian Bök’s Eunoia Sean Braune hristian Bök is one of the foremost Canadian poets of the avant-garde. During a conversation between Bök and Darren Wershler-Henry for Brick, Wershler-Henry noted that Eunoia Cis the fastest selling book of poetry since Robert Service’s Songs of a Sourdough (119). The book’s success has left Bök baffled: “I wonder sometimes whether or not people are simply reading it because of its freakish character, passing by it like a carload of vacationers, slowing down to gawk at a two-headed calf by the side of the road” (Brick 120). Its success is indeed surprising because of the work’s experiment- al nature and avant-garde status. Experimental literature is typically not commercially fruitful, which makes the success of Eunoia all the more surprising. Perhaps Bök is correct when he compares his work to a “two-headed calf” because of its peculiar success. The book’s formid- able structural constraint requires a gloss or “skeleton key” to assist in approaching and decoding the work. This essay is intended to facilitate such an approach. The obsessive construction of Eunoia is influenced by the textual constraints of the French literary group called the “Oulipo.”1 The Oulipo was a “workshop” where many prominent French writers met to discuss the possibility of producing texts without the aid of “inspira- tion.” Rather than rely on a “lightning bolt” of inspiration to strike, the Oulipians invented mathematical constraints that could produce litera- ture with or without the aid of a writer.2 These constraints can be seen in the syntactical parallelism, internal rhyme schemes, and the inverse- lipogram3 of the book’s textual structure. -

Gadsby-By-Ernest-Vincent-Wright.Pdf

This free e-book has been downloaded from www.holybooks.com http://www.holybooks.com/gadsby-ernest-vincent-wright-without-letter-e/ Gadsby Gadsby: a story of over 50,000 words without using the letter "E" by Ernest Vincent Wright Introduction by the Author: THE ENTIRE MANUSCRIPT of this story was written with the E type-bar of the typewriter tied down; thus making it impossible for that letter to be printed. This was done so that none of that vowel might slip in, accidentally; and many did try to do so! There is a great deal of information as to what Youth can do, if given a chance; and, though it starts out in somewhat of an impersonal vein, there is plenty of thrill, rollicking comedy, love, courtship, marriage, patriotism, sudden tragedy, a determined stand against liquor, and some amusing political aspirations in a small growing town. In writing such a story, —purposely avoiding all words containing the vowel E, there are a great many difficulties. The greatest of these is met in the past tense of verbs, almost all of which end with “-ed.” Therefore substitutes must be found; and they are very few. This will cause, at times, a somewhat monotonous use of such words as “said;” for neither “replied,” “answered” nor “asked” can be used. Another difficulty comes with the elimination of the common couplet “of course,” and its very common connective, “consequently;” which will unavoidably cause “bumpy spots.” The numerals also cause plenty of trouble, for none between six and thirty are available. When introducing young ladies into the story, this is a real barrier; for what young woman wants to have it known that she is over thirty? And this restriction on numbers, of course taboos all mention of dates. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Reading from A to Z: The Alphabetic Sequence in Experimental Literature and Visual Art Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/10m9712j Author Ardam, Jacquelyn Wendy Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading from A to Z: The Alphabetic Sequence in Experimental Literature and Visual Art A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Jacquelyn Wendy Ardam 2015 © Copyright by Jacquelyn Wendy Ardam 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading from A to Z: The Alphabetic Sequence in Experimental Literature and Visual Art by Jacquelyn Wendy Ardam Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Michael A. North, Chair “Reading from A to Z” argues for the significance of the alphabetic sequence to the transatlantic experimental literature and visual art from the modern period to the present. While it may be most familiar to us as a didactic device to instruct children, various experimental writers and avant-gardists have used the alphabetic sequence to structure some of their most radical work. The alphabetic sequence is a culturally-meaningful trope with great symbolic import; we are, after all, initiated into written discourse by learning our ABCs, and the sequence signifies logic, sense, and an encyclopedic and linear way of thinking about and representing the world. But the string of twenty-six arbitrary signifiers also represents rationality’s complete opposite; the alphabet is just as potent a symbol and technology of nonsense, arbitrariness, and (children’s) play. -

ABC-Book-Project-Catalogue.Pdf

1 Alphabet Books Through the Ages “Of all the achievements of the human mind, the birth of the alphabet is the most momentous.” – Frederic Goudy, type designer. In 1658, Johann Comenius’s picture book Orbis Sensualium Pictus was published. It was the first time the alphabet provided the cohesion for a set of themed pictures and illuminated sounds. Thus, the alphabet book was born. Here is a selection of English language alphabet books from the late 18th century to the present day. These books illustrate the changes in alphabetic education for young children in England, the United States, and Canada. The authors and illustrators who created these books were influenced by the political and social contexts of their worlds. For example, there is a gap in our display for the 1940s. Publishing declined dramatically during the war and took a few years to regain its earlier production. This exhibit reflects this. Alphabet book creators were also constrained by the printing technologies and the publishing industries they worked within. As both printing and publishing changed and advanced, so too did the alphabet books being produced. These changes over time are evident in the printed pages seen in this display. The alphabet book as a learning tool has taken innumerable forms. Its prime purpose is to unlock the symbols, sounds, and uses of letters for small children. The “A is for Apple, B is for Ball…” pattern of letter, word, and image to match has been produced in a variety of ways. The exhibit showcases alphabet books from the last two centuries representing this variety. -

Exercises in (Mathematical) Style

Preface . it is extraordinary how fertile in properties the triangle is. Every- one can try his hand. Treatise on the Arithmetical Triangle, Blaise Pascal At the age of twenty-one, he wrote a treatise upon the binomial theorem, which has had a European vogue. On the strength of it he won the mathematical chair at one of our smaller universities, and had, to all appearances, a most brilliant career before him. (Sherlock Holmes about James Moriarty) The Final Problem, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Who has anything new to say about the binomial theorem at this late date? At any rate, I am certainly not the man to know. (Moriarty to Watson) The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, Nicholas Meyer . every style of reasoning introduces a great many novelties, in- cluding new types of (i) objects, (ii) evidence, (iii) sentences, new ways of being a candidate for truth or falsehood, (iv) laws, or at any rate modalities, (v) possibilities. One will also notice, on occasion, new types of classification, and new types of explanations. Ian Hacking According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a pastiche is a work that in- corporates several different styles, drawn from a variety of sources, in the style of someone else. In this book I am consciously imitating the work Exercices de Style (Éditions Gallimard, Paris, 1947) of Raymond Queneau (1903–1976). In a page, Queneau introduces a banal story of a man on a bus that he then tells in 99 different ways. The manners of speech include philosophical, metaphorical, onomatopoeic, telegraphic; also the forms of an advertisement, a short play, a libretto, a tanka; in passive voice, imperfect tense; and so on.