The Sargasso Sea for Atlantic Sea Turtles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Assessing the Economic Contribution of Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services in the Sargasso Sea

NICHOLAS INSTITUTE REPORT Assessing the Economic Contribution of Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services in the Sargasso Sea L. Pendleton* F. Krowicki and P. Strosser† J. Hallett-Murdoch‡ *Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, Duke University † ACTeon ‡ Murdoch Marine October 2014 NI R 14-05 Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions Report NI R 14-05 First published October 2014 Revised April 2015 Assessing the Economic Contribution of Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services in the Sargasso Sea L. Pendleton* F. Krowicki and P. Strosser† J. Hallett-Murdoch‡ *Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, Duke University † ACTeon ‡ Murdoch Marine Acknowledgments Support for this report was provided by the World Wide Fund for Nature Marine Protected Area Action Agenda and the Secretariat of the Sargasso Sea Commission. External peer review of the original manuscript was managed by Kristina Gjerde of the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Useful comments and expert subject matter guidance were provided by Rashid Sumaila, Luke Brander, David Freestone, Howard Roe, Dan Laffoley, Brian Luckhurst, and Emilie Reuchlin-Hugenholtz. All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the authors alone. Additional support for Pendleton’s time was provided by the “Laboratoire d’Excellence” LabexMER (ANR-10-LABX-19) and the French government under the program Investissements d’Avenir. How to cite this report Pendleton, L., F. Krowicki., P. Strosser, and J. Hallett-Murdoch. Assessing the Economic Contribution of Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services in the Sargasso Sea. NI R 14-05. Durham, NC: Duke University. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Sargasso Sea ecosystem generates a variety of goods and services that benefit people. -

Beach Dynamics and Impact of Armouring on Olive Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys Olivacea) Nesting at Gahirmatha Rookery of Odisha Coast, India

Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences Vol. 45(2), February 2016, pp. 233-238 Beach dynamics and impact of armouring on olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) nesting at Gahirmatha rookery of Odisha coast, India Satyaranjan Behera1, 2, Basudev Tripathy3*, K. Sivakumar2, B.C. Choudhury2 1Odisha Biodiversity Board, Regional Plant Resource Centre Campus, Nayapalli, Bhubaneswar-15 2Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, PO Box 18, Chandrabani, Dehradun – 248 001, India. 3Zoological Survey of India, Prani Vigyan Bhawan, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053 (India) *[E. mail:[email protected]] Received 28 March 2014; revised 18 September 2014 Gahirmatha arribada beach are most dynamic and eroding at a faster rate over the years from 2008-09 to 2010-11, especially during the turtles breeding seasons. Impact of armouring cement tetrapod on olive ridley sea turtle nesting beach at Gahirmatha rookery of Odisha coast has also been reported in this study. This study documented the area of nesting beach has reduced from 0.07 km2to 0.06 km2. Due to a constraint of nesting space, turtles were forced to nest in the gap of cement tetrapods adjacent to the arribada beach and get entangled there, resulting into either injury or death. A total of 209 and 24 turtles were reported to be injured and dead due to placement of cement tetrapods in their nesting beach during 2008-09 and 2010-11 respectively. Olive ridley turtles in Odisha are now exposed to many problems other than fishing related casualty and precautionary measures need to be taken by the wildlife and forest authorities to safeguard the Olive ridleys and their nesting habitat at Gahirmatha. -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

Sargassum White Paper - Sargassum Outbreak in the Caribbean: Challenges, Opportunities and Regional Situation

UNITED NATIONS EP Distr. LIMITED UNEP(DEPI)/CAR WG.40/ INF8 30 October 2018 Original: ENGLISH Eighth Meeting of the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) to the Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) in the Wider Caribbean Region Panama City, Panama, 5 ‐ 7 December 2018 Sargassum White Paper - Sargassum Outbreak in the Caribbean: Challenges, Opportunities and Regional Situation For reasons of economy and the environment, Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copies of the Working and Information documents to the Meeting, and not to request additional copies. *This document has been reproduced without formal editing. Sargassum Outbreak in the Caribbean: Challenges, Opportunities & Regional Situations by the SPAW Sub-Programme at the UN Environment CEP Secretariat Conceptual background Pelagic Sargassum is a type of brown alga or seaweed that can form large floating mats that are often referred to as “golden tides”. Field surveys and satellite maps indicate that Sargassum blossoms naturally in the Tropical South Atlantic and in the North Atlantic including the Sargasso Sea, over an area spanning 2 million square miles in the warm waters of the Atlantic Ocean. In the last few years, there have been several episodes of unusual quantities of two species of Sargassum, S. natans and S. fluitans, reaching the coasts of many of the islands of the Caribbean Sea, and countries in South, Central, and North America. What appears to have been an unprecedented quantity of pelagic Sargassum reached Caribbean islands in the spring of 20111. Anomalous amounts of Sargassum also reached the coasts of Sierra Leone and the Gulf of Guinea in June 2011. -

Green Sea Turtle in the New England Aquarium Has Been in Captivity Since 1970, and Is Believed to Be Around 80 Years Old (NEAQ 2013)

Species Status Assessment Class: Reptilia Family: Cheloniidae Scientific Name: Chelonia mydas Common Name: Green turtle Species synopsis: The green turtle is a marine turtle that was originally described by Linnaeus in 1758 as Testudo mydas. In 1868 Marie Firmin Bocourt named a new species of sea turtle Chelonia agassizii. It was later determined that these represented the same species, and the name became Chelonia mydas. In New York, the green turtle can be found from July – November, with individuals occasionally found cold-stunned in the winter months (Berry et al. 1997, Morreale and Standora 1998). Green turtles are sighted most frequently in association with sea grass beds off the eastern side of Long Island. They are observed with some regularity in the Peconic Estuary (Morreale and Standora 1998). Green turtles experienced a drastic decline throughout their range during the 19th and 20th centuries as a result of human exploitation and anthropogenic habitat degradation (NMFS and USFWS 1991). In recent years, some populations, including the Florida nesting population, have been experiencing some signs of increase (NMFS and USFWS 2007). Trends have not been analyzed in New York; a mark-recapture study performed in the state from 1987 – 1992 found that there seemed to be more green turtles at the end of the study period (Berry et al. 1997). However, changes in temperature have lead to an increase in the number of cold stunned green turtles in recent years (NMFS, Riverhead Foundation). Also, this year a record number of nests were observed at nesting beaches in Flordia (Mote Marine Laboratory 2013). 1 I. -

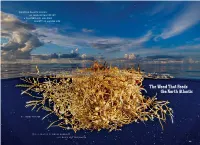

The Weed That Feeds the North Atlantic

DRIFTING PLANTS KNOWN AS SARGASSUM SUPPORT A COMPLEX AND AMAZING VARIETY OF MARINE LIFE. The Weed That Feeds the North Atlantic BY JAMES PROSEK PHOTOGRAPHS BY DAVID DOUBILET AND DAVID LIITTSCHWAGER 129 Hatchling sea turtles, like this juvenile log- gerhead, make their way from the sandy beaches where they were born toward mats of sargassum weed, finding food and refuge from predators during their first years of life. PREVIOUS PHOTO A clump of sargassum weed the size of a soccer ball drifts near Bermuda in the slow swirl of the Sargasso Sea, part of the North Atlantic gyre. A weed mass this small may shelter thousands of organisms, from larval fish to seahorses. DAVID DOUBILET (BOTH) 130 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC THE WEED THAT FEEDS THE NORTH ATLANTIC 131 ‘There’s nothing like it in any other ocean,’ says marine biologist Brian Lapointe. ‘There’s nowhere else on our blue planet that supports such diversity in the middle of the ocean—and it’s because of the weed.’ LAPOINTE IS TALKING about a floating seaweed known as sargassum in a region of the Atlantic called the Sargasso Sea. The boundaries of this sea are vague, defined not by landmasses but by five major currents that swirl in a clockwise embrace around Bermuda. Far from any main- land, its waters are nutrient poor and therefore exceptionally clear and stunningly blue. The Sargasso Sea, part of the vast whirlpool known as the North Atlantic gyre, often has been described as an oceanic desert—and it would appear to be, if it weren’t for the floating mats of sargassum. -

Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean Volume

ISBN 0-9689167-4-x Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean (Davis Strait, Southern Greenland and Flemish Cap to Cape Hatteras) Volume One Acipenseriformes through Syngnathiformes Michael P. Fahay ii Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean iii Dedication This monograph is dedicated to those highly skilled larval fish illustrators whose talents and efforts have greatly facilitated the study of fish ontogeny. The works of many of those fine illustrators grace these pages. iv Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean v Preface The contents of this monograph are a revision and update of an earlier atlas describing the eggs and larvae of western Atlantic marine fishes occurring between the Scotian Shelf and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (Fahay, 1983). The three-fold increase in the total num- ber of species covered in the current compilation is the result of both a larger study area and a recent increase in published ontogenetic studies of fishes by many authors and students of the morphology of early stages of marine fishes. It is a tribute to the efforts of those authors that the ontogeny of greater than 70% of species known from the western North Atlantic Ocean is now well described. Michael Fahay 241 Sabino Road West Bath, Maine 04530 U.S.A. vi Acknowledgements I greatly appreciate the help provided by a number of very knowledgeable friends and colleagues dur- ing the preparation of this monograph. Jon Hare undertook a painstakingly critical review of the entire monograph, corrected omissions, inconsistencies, and errors of fact, and made suggestions which markedly improved its organization and presentation. -

Spirorchiidiasis in Stranded Loggerhead Caretta Caretta and Green Turtles Chelonia Mydas in Florida (USA): Host Pathology and Significance

Vol. 89: 237–259, 2010 DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published April 12 doi: 10.3354/dao02195 Dis Aquat Org OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Spirorchiidiasis in stranded loggerhead Caretta caretta and green turtles Chelonia mydas in Florida (USA): host pathology and significance Brian A. Stacy1,*, Allen M. Foley2, Ellis Greiner3, Lawrence H. Herbst4, Alan Bolten5, Paul Klein6, Charles A. Manire7, Elliott R. Jacobson1 1University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, PO Box 100136, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 2Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Jacksonville Field Laboratory, 370 Zoo Parkway, Jacksonville, Florida 32221, USA 3University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine, Infectious Diseases and Pathology, PO Box 110880, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 4Department of Pathology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York 10461, USA 5Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, University of Florida, PO Box 118525, Gainesville, Florida 32611, USA 6Department of Pathology, Immunology, and Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 7Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, 1600 Ken Thompson Parkway, Sarasota, Florida 34236, USA ABSTRACT: Spirorchiid trematodes are implicated as an important cause of stranding and mortality in sea turtles worldwide. However, the impact of these parasites on sea turtle health is poorly understood due to biases in study populations and limited or missing data for some host species and regions, includ- ing the southeastern United States. We examined necropsy findings and parasitological data from 89 log- gerhead Caretta caretta and 59 green turtles Chelonia mydas that were found dead or moribund (i.e. stranded) in Florida (USA) and evaluated the role of spirorchiidiasis in the cause of death. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

Background on Sea Turtles

Background on Sea Turtles Five of the seven species of sea turtles call Virginia waters home between the months of April and November. All five species are listed on the U.S. List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants and classified as either “Threatened” or “Endangered”. It is estimated that anywhere between five and ten thousand sea turtles enter the Chesapeake Bay during the spring and summer months. Of these the most common visitor is the loggerhead followed by the Kemp’s ridley, leatherback and green. The least common of the five species is the hawksbill. The Loggerhead is the largest hard-shelled sea turtle often reaching weights of 1000 lbs. However, the ones typically sighted in Virginia’s waters range in size from 50 to 300 lbs. The diet of the loggerhead is extensive including jellies, sponges, bivalves, gastropods, squid and shrimp. While visiting the Bay waters the loggerhead dines almost exclusively on horseshoe crabs. Virginia is the northern most nesting grounds for the loggerhead. Because the temperature of the nest dictates the sex of the turtle it is often thought that the few nests found in Virginia are producing predominately male offspring. Once the male turtles enter the water they will never return to land in their lifetime. Loggerheads are listed as a “Threatened” species. The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle is the second most frequent visitor in Virginia waters. It is the smallest of the species off Virginia’s coast reaching a maximum weight of just over 100 lbs. The specimens sited in Virginia are often less than 30 lbs. -

Geography Notes.Pdf

THE GLOBE What is a globe? a small model of the Earth Parts of a globe: equator - the line on the globe halfway between the North Pole and the South Pole poles - the northern-most and southern-most points on the Earth 1. North Pole 2. South Pole hemispheres - half of the earth, divided by the equator (North & South) and the prime meridian (East and West) 1. Northern Hemisphere 2. Southern Hemisphere 3. Eastern Hemisphere 4. Western Hemisphere continents - the largest land areas on Earth 1. North America 2. South America 3. Europe 4. Asia 5. Africa 6. Australia 7. Antarctica oceans - the largest water areas on Earth 1. Atlantic Ocean 2. Pacific Ocean 3. Indian Ocean 4. Arctic Ocean 5. Antarctic Ocean WORLD MAP ** NOTE: Our textbooks call the “Southern Ocean” the “Antarctic Ocean” ** North America The three major countries of North America are: 1. Canada 2. United States 3. Mexico Where Do We Live? We live in the Western & Northern Hemispheres. We live on the continent of North America. The other 2 large countries on this continent are Canada and Mexico. The name of our country is the United States. There are 50 states in it, but when it first became a country, there were only 13 states. The name of our state is New York. Its capital city is Albany. GEOGRAPHY STUDY GUIDE You will need to know: VOCABULARY: equator globe hemisphere continent ocean compass WORLD MAP - be able to label 7 continents and 5 oceans 3 Large Countries of North America 1. United States 2. Canada 3.