Handbook for EMS Medical Directors March 2012 This Page Was Intentionally Left Blank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ED Medical Director Roles and Responsibilities Job Description, July 2015 Page 2

ED Medical Director Roles and Responsibilities Job Description The specific role and responsibilities of an emergency department (ED) medical director vary based on the size, characteristics, and leadership structure of the department. As an example, in some departments portions of the duties specified below may be the responsibility of the department chair, vice-chair, medical director, or other members of the ED leadership team. Nevertheless, the following are leadership tasks that should be considered in a description of the roles and responsibilities of the ED medical director. Clinical and Service Operations Collaborate with ED nursing leadership, emergency physicians and advanced practice provider (APP) staff, and hospital administration to ensure the ED care delivery model achieves high- quality emergency care and evolves to match the needs of the patients, the department, the hospital, and the community. Develop, maintain, update, and implement departmental policies, procedures, and protocols. Ensure providers are aware of and compliant with departmental, hospital, and medical staff policies. Work to ensure that medical staff policies support the department and hospital vision for ED care. Coordinate staffing and scheduling of physicians and APPs. Perform quality assurance and lead improvement initiatives within the department. Serve as chair or co-chair of the Emergency Services Committee or its equivalent. Provide input into the operating and capital budgets of the department. Monitor patient experience and patient flow. Design and implement process improvement strategies to improve and optimize these areas. Regulatory Monitor ED-related regulatory issues and ensure ongoing regulatory compliance. Educate staff on regulatory issues and requirements. Prepare for and participate in accreditation or certification surveys involving the ED. -

EMS Medical Director Guidebook

Medical Director Guidebook May 2016 Maine Emergency Medical Services Department of Public Safety 152 State House Station Augusta, ME 04333 www.maine.gov/ems Authors Christopher Paré, Paramedic J. Matthew Sholl, M.D., M.P.H. Eric Wellman, Paramedic Contributors Jay Bradshaw Jonnathan Busko, MD Myles Block, Paramedic Emily Carter, Paramedic Marlene Cormier, M.D. Shawn Evans, Paramedic Kevin Kendall, M.D. Rick Petrie, Paramedic Tim Pieh, M.D. Kerry Pomelow, Paramedic Mike Schmitz, D.O. Nate Yerxa, Paramedic Table of Contents Foreword 1 The Maine EMS System Structure 2 Legal Aspects & System Rules 6 EMS Systems 18 Maine EMS Medical Director Qualifications 23 Medical Oversight 31 EMS Personnel & Providers 36 EMS Operations 38 Interfacility Patient Transport 49 EMS Education 51 Grants & System Funding 55 Quality Assurance & System Improvement 57 Maine EMS Protocols & Standing Orders 65 Appendix A: Disaster Planning 70 Appendix B: Wilderness EMS 80 Appendix C: Tactical EMS 82 Appendix D: Death Situations for Medical Responders 83 Appendix E: Maine EMS Scope of Practice by License Level 88 Appendix F: Maine EMS Interfacility Transport: Decision Tree and Scope of Practice for Transfer by 93 License Level Appendix G: Recommended Service Policies 99 Appendix H: Checklist for the new medical director 100 References 101 Glossary of Acronyms 103 Index 104 FOREWORD The Maine EMS Medical Director’s Guidebook was designed to provide physicians and EMS services with direction on how to navigate the Maine EMS system. Our goal with this guidebook is to educate and in- form all users of the system to the role of EMS physician medical direction. -

Paramedic Treatment Protocols

Paramedic Treatment Protocols West Virginia Office of Emergency Medical Services EMS Protocols Paramedic Treatment Protocol TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Acknowledgments Using the Protocols INITIAL TREATMENT / UNIVERSAL PATIENT CARE TRAUMA 4100 Severe External Bleeding 4101 Selective Spinal Immobilization 4102 Chest Trauma 4104 Abdominal Trauma 4105 Musculoskeletal Trauma 4106 Head Trauma 4107 Hypoperfusion / Shock 4108 Traumatic Arrest 4109 Burns 4110 Eye Injuries 4111 Tranexamic Acid (TXA) 4112 CARDIAC 4200 Chest Pain 4202 Severe Hypertension 4203 Cardiac Arrest 4205 Tachycardia 4208 Symptomatic Bradycardia 4211 Right Ventricular AMI 4213 Return of Spontaneous Circulation - ROSC 4214 RESPIRATORY 4300 Bronchospasm 4302 Pulmonary Edema 4303 Inhalation Injury 4304 Airway Obstruction 4305 PEDIATRIC 4400 Medical Assessment 4401 Hypoperfusion / Shock 4402 Seizures 4403 Child Neglect / Abuse 4404 Sudden Infant Death Syndrome 4405 Cardiac Arrest 4406 West Virginia Office of Emergency Medical Services – Statewide Protocols Page 1 of 3 Paramedic Treatment Protocol TABLE OF CONTENTS Cardiac Dysrhythmias 4407 Trauma Assessment 4408 Fever 4409 Newborn Infant Care 4410 Pediatric Diabetic Emergencies 4411 Allergic Reaction / Anaphylaxis 4412 Bronchospasm 4413 ENVIRONMENTAL 4500 Allergic Reaction / Anaphylaxis 4501 Heat Exposure 4502 Cold Exposure 4503 Snake Bite 4504 Near Drowning / Drowning 4505 MEDICAL 4600 Hypoperfusion / Shock 4601 Stroke / TIA 4602 Seizures 4603 Diabetic Emergencies 4604 Unconscious / Altered Mental Status 4605 Overdose / Ingestion -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

Abbreviations and Acronyms ABBREVIATIONS and ACRONYMS A A: Airborne AAC: Army Acquisition Corps AAPA: American Academy of Physician Assistants AATS: ARNG Aviation Training Site ABLS: Advanced Burn Life Support ABN DIV: airborne division ABSITE: American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination ACAT: acquisition category ACE: ask, care, escort ACEP: American College of Emergency Physicians ACFT: Army Combat Fitness Test ACGME: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education ACM: Army Capability Manager ACR: armored cavalry regiment ACU: Army combat uniform AD: active duty ADDIE: analysis, design, develop, implement, evaluate ADP: AMEDD Distribution Plan ADSO: active duty service obligation ADTMC: algorithm-directed troop medical care AFAB: assigned female at birth AFRICOM: Africa Command AFSCP: Army Flight Surgeon Course–Primary AGR: Active Guard Reserve AHA: American Heart Association AHLTA: Armed Forces Health Longitudinal Technology Application AHO: allied health officer AHS: Army health system AHSMS: Allied Health Sciences Military School AI: associate investigator AIM.2: Assignment Interactive Module Version 2 AIT: advanced individual training 531 US Army Physician Assistant Handbook ALARACT: All Army Activities message ALP: accepted list position ALS: Advanced Life Support ALSE: Aviation Life Support Equipment (course) AMA: American Medical Association AMAB: assigned male at birth AMEDD: Army Medical Department AMEDDB: Army Medical Department Board AMH: Army Medical Home AMHRR: Army Military Human Resource Record AMP: aviation -

Ambulance Helicopter Contribution to Search and Rescue in North Norway Ragnar Glomseth1, Fritz I

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Glomseth et al. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine (2016) 24:109 DOI 10.1186/s13049-016-0302-8 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Open Access Ambulance helicopter contribution to search and rescue in North Norway Ragnar Glomseth1, Fritz I. Gulbrandsen2,3 and Knut Fredriksen1,4* Abstract Background: Search and rescue (SAR) operations constitute a significant proportion of Norwegian ambulance helicopter missions, and they may limit the service’s capacity for medical operations. We compared the relative contribution of the different helicopter resources using a common definition of SAR-operation in order to investigate how the SAR workload had changed over the last years. Methods: We searched the mission databases at the relevant SAR and helicopter emergency medical service (HEMS) bases and the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (North) for helicopter-supported SAR operations within the potential operation area of the Tromsø HEMS base in 2000–2010. We defined SAR operations as missions over land or sea within 10 nautical miles from the coast with an initial search phase, missions with use of rescue hoist or static rope, and avalanche operations. Results: There were 769 requests in 639 different SAR operations, and 600 missions were completed. The number increased during the study period, from 46 in 2000 to 77 in 2010. The Tromsø HEMS contributed with the highest number of missions and experienced the largest increase, from 10 % of the operations in 2000 to 50 % in 2010. Simple terrain and sea operations dominated, and avalanches accounted for as many as 12 % of all missions. -

2017 Research Abstracts Selection for Podium Or Poster Presentation

2017 Research Abstracts Selection for Podium or Poster Presentation TOP PODIUM PRESENTATION Social Media and Military Medicine SFC Paul E. Loos, NCOIC Surgery, Anesthesia, Records and Reports Section, Special Forces Medical Sergeants Course, Joint Special Operations Medical Training Facility, Fort Bragg, NC Background: As technology in communications advances, best practices in tactical or military medicine can be shared at the speed of creation. Currently best practices are spread through the publishing of texts, scholarly journal articles, word of mouth, or during periodic refresher courses. This leaves many tactical medical providers and medical directors using different protocols and recommendations for patient care. The goal of my presentation is to inform and empower medical providers to more efficiently disseminate needed medical information to medics in their charge utilizing modern communications techniques. Methods: Trial and error and 3 years of experience. Results: 160,000 hits on our website made by over 70,000 unique IP addresses around the world on our blog posts, podcasts and recommendations. Discussion: Due to a variety of reasons, military medics are not getting the most up to date information regarding the treatment of casualties throughout the gamut of tactical medicine. I will submit a layered approach using multiple solutions in improving communication of current best practices and recommendations from unit surgeons down to the end-user medic on the ground. This will include discussions on social media use, and etiquette, by military members to include different social media platforms as well as current USSOCOM and DOD policy. Depending on the content to be released, various social media sites are better used for certain purposes. -

ESSENTIAL CORE FUNCTIONS Responsibilities Knowledge Skill

ESSENTIAL CORE FUNCTIONS Responsibilities Knowledge Skill A Guide for the Consultant Pharmacist, Director of Nursing, Medical Director, and Nursing Home Administrator in Long Term Care Organizations As put forth by the Long Term Care Professional Leadership Council consisting of: The American College of Health Care Administrators The American Medical Directors Association The American Society of Consultant Pharmacists and The National Association of Directors of Nursing Administration ______________________________________________________________________________ The Guide must be read in conjunction with all State and Federal statute and regulations governing licensed nursing homes and the employer’s policies and position descriptions. The Guide is not intended to replace or modify any of these State and Federal statutes, regulations or employer policies. In the event of ambiguity or inconsistency, rules and regulations must take precedence. 1 Long Term Care Professional Leadership Council Charter The Long Term Care Professional Leadership Council consists of the leaders of the major professional leadership associations* of long-term care: ACHCA, AMDA, ASCP, and NADONA. This Council was formed to foster collaboration in defining and addressing issues related to standards for quality care in long-term care facilities, including: • Advancing consistent standards, positions, and recommendations pertaining to long-term care • Promoting evidence-based approaches to common problems and risks of long-term care patients and residents • Coordinating -

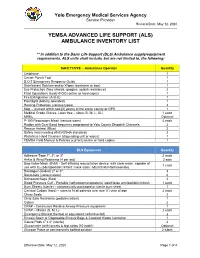

(Als) Ambulance Inventory List

Yolo Emergency Medical Services Agency Service Provider Revised Date: May 12, 2020 YEMSA ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT (ALS) AMBULANCE INVENTORY LIST ** In addition to the Basic Life Support (BLS) Ambulance supply/equipment requirements, ALS units shall include, but are not limited to, the following: SAFETY/PPE – Ambulance Operator Quantity Cellphone 1 Center Punch Tool 1 D.O.T Emergency Response Guide 1 Disinfectant Solution and/or Wipes (container or box) 1 Eye Protection (face shields, goggles, splash resistance) 2 Field Operations Guide (FOG) online or hard copies 1 Fire Extinguisher (A-B-C) 1 Flashlight (battery operated) 1 Hearing Protection (various types) 2 Map – (current within two [2] years) of the entire county or GPS 1 Medical Grade Gloves, Latex free – sizes (S, M, L, XL) 1 each MREs Optional P-100 Respiratory Mask (various sizes) 4 each Radios with Dual Band frequency programed to Yolo County Dispatch Channels 2 Rescue Helmet (Blue) 2 Safety Vest meeting ANSI/OSHA standards 2 Waterless Hand Cleanser (dispensing unit or wipes) 1 YEMSA Field Manual & Policies (current) online or hard copies 1 BLS Equipment Quantity Adhesive Tape 1", 2", or 3" 2 each Ankle & Wrist Restraints (4 per set) 2 sets Bag-Valve-Mask (BVM) - Self-inflating resuscitation device, with clear mask, capable of 1 each use with O2 (adult/pediatric/infant; mask sizes: adult/child/infant/neonate) Bandages (Rolled) 2" or 3" 3 Band-Aids (various sizes) 6 Biohazard Bags (Red) 2 Blood Pressure Cuff - Portable (sphygmomanometers) (adult/large arm/pediatric/infant) 1 each -

NAEMT News Fall 2017 for WEB 09.19.17

FALL 2017 In This Issue Are You Prepared? Results naemtnews 5 of NAEMT’s Survey on MCI A quarterly publication of the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians Readiness Meet NAEMT’s New Medical 12 Director, Dr. Craig Manifold EMS Agenda for the Future 2050: Please Remember to Vote! 16 NAEMT Elections Oct. 15 to 28 Establishing a New Vision for the Profession More than 20 years have passed since the original EMS Agenda for the Future, What is an Agenda for the Future published in 1996, outlined a vision for EMS. The agenda described an EMS that is and why is it important to have one? fully integrated with the healthcare system, provides acute injury treatment as well as An Agenda for the Future is a follow-up care, and participates in preventing and treating chronic conditions. vision, a roadmap and a strategy that EMS has made some strides toward realizing that vision. Developments such as describes where you are today and regionalized systems of STEMI (ST-elevation myocardial infarction) care and MIH-CP how you will get to someplace new and (mobile integrated healthcare-community paramedicine) have helped to show the rest different. When I think about history, of healthcare the value of partnering with EMS. JFK [President John F. Kennedy] did that Yet there is still a long way to go. Recommendations regarding funding EMS for in his 1961 speech when he promised services other than transport, legislative change to allow EMS to provide treatment that that we would land a man on the moon doesn’t end at the hospital, and fully integrating EMS into the healthcare continuum are and safely return him back to earth by still in the early stages. -

Healthy Choices Get a Head Start on Great Health

Healthy Choices Get a Head Start on Great Health 2015 Benefits Guide MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Non-union MedStar Health Research Institute MedStar National Rehabilitation Network Non-hospital Based Businesses, South Table of Contents 1 Enrollment Checklist 2 Enrollment Guidelines 3 Online Enrollment Instructions 4 Wellness Resources 4 Your Medical Plan Options 5 COBRA Continued Benefit Coverage 6 2015 Medical Plan Options Chart 8 Prescription Drug Plans 9 Your Dental Plan Options 11 Your Vision Plan Option 12 Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) 14 Life Insurance 14 Accidental Death and Dismemberment Insurance 15 Disability Plans 15 Universal Life, Critical Illness and Accident Insurances 16 Legal Resources 16 MedStar Associate Advantages 18 Contact Information i 2015 Annual Enrollment Choices For Healthy Living MedStar Health provides a comprehensive benefits If you are a benefit-eligible associate, take advantage of package for you and your family—MedStar Total MedStar Total Rewards. You must enroll online to receive Rewards. You are responsible for selecting the best mix medical, dental, vision, flexible spending accounts, of benefits to meet your needs and actively managing supplemental life, supplemental accidental death and these benefits and your health throughout the year. Use dismemberment, dependent life, or legal coverage in 2015. this guide to select your MedStar Total Rewards health and welfare package for 2015. Enrollment Checklist Read through this guide to design your MedStar Total Rewards package for 2015. Medical Accidental Death and Dismemberment Elect a healthcare coverage option. Insurance • MedStar Select Plan Consider if additional coverage would give your • CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield Preferred family more peace of mind. Provider Organization (PPO) Plan • Kaiser Permanente Health Maintenance Disability Organization (HMO) Plan MedStar provides full-time associates with short- and long-term disability coverage equal to 60 Dental percent of your base pay, at no cost to you. -

Kern County Sheriff's Office Search and Rescue Policies and Procedures Table of Contents

KERN COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE SEARCH AND RESCUE POLICIES AND PROCEDURES ______________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________________________________ A -- INTRODUCTION A-100 Introduction-Mission Statement A-110 Manual Revisions A-200 Definitions A-300 Organizational Structure B -- RESPONSIBILITIES OF PERSONNEL B-100 Duties of Search and Rescue Coordinator B-200 Duties of Search and Rescue Members C -- SELECTION OF SEARCH AND RESCUE MEMBERSHIP C-100 Selection of Members C-200 Probationary Period C-300 Leave of Absence C-400 Termination D -- SEARCH AND RESCUE RANK STRUCTURE D-100 Rank Structure and Responsibilities D-200 Rank Insignia E -- SEARCH AND RESCUE TRAINING E-100 Training E-200 Training Forecast E-300 Training Documentation F -- SEARCH AND RESCUE MEETINGS F-100 Meetings Page 1 of 1 _____________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________________________________ G -- ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES G-100 Call-Out Procedures - In County G-200 Call-Out Procedures - Mutual Aid G-300 Aircraft Operations G-400 Incident Command System G-500 Uniforms and Appearance G-600 Donations and Grants G-700 Discipline G-800 Firearms G-900 Injuries G-1000 Media Relations G-1100 Medical Responsibilities G-1200 Member Compensation G-1300 Vehicle Operation G-1400 SAR BLS Policy Page 2 of 2 Page 3 of 3 KERN COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE SEARCH AND RESCUE POLICIES AND PROCEDURES -

Emergency Medical Services Statutes and Regulations

Emergency Medical Services Statutes and Regulations Printed: August 2016 Effective: September 11, 2016 1 9/16/2016 Statutes and Regulations Table of Contents Title 63 of the Oklahoma Statutes Pages 3 - 13 Sections 1-2501 to 1-2515 Constitution of Oklahoma Pages 14 - 16 Article 10, Section 9 C Title 19 of the Oklahoma Statutes Pages 17 - 24 Sections 371 and 372 Sections 1- 1201 to 1-1221 Section 1-1710.1 Oklahoma Administrative Code Pages 25 - 125 Chapter 641- Emergency Medical Services Subchapter 1- General EMS programs Subchapter 3- Ground ambulance service Subchapter 5- Personnel licenses and certification Subchapter 7- Training programs Subchapter 9- Trauma referral centers Subchapter 11- Specialty care ambulance service Subchapter 13- Air ambulance service Subchapter 15- Emergency medical response agency Subchapter 17- Stretcher aid van services Appendix 1 Summary of rule changes Approved changes to the June 11, 2009 effective date to the September 11, 2016 effective date 2 9/16/2016 §63-1-2501. Short title. Sections 1-2502 through 1-2521 of this title shall be known and may be cited as the "Oklahoma Emergency Response Systems Development Act". Added by Laws 1990, c. 320, § 5, emerg. eff. May 30, 1990. Amended by Laws 1999, c. 156, § 1, eff. Nov. 1, 1999. NOTE: Editorially renumbered from § 1-2401 of this title to avoid a duplication in numbering. §63-1-2502. Legislative findings and declaration. The Legislature hereby finds and declares that: 1. There is a critical shortage of providers of emergency care for: a. the delivery of fast, efficient emergency medical care for the sick and injured at the scene of a medical emergency and during transport to a health care facility, and b.