The New England Puritans and the Name of God

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relationship of Yahweh and El: a Study of Two Cults and Their Related Mythology

Wyatt, Nicolas (1976) The relationship of Yahweh and El: a study of two cults and their related mythology. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2160/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] .. ýýý,. The relationship of Yahweh and Ell. a study of two cults and their related mythology. Nicolas Wyatt ý; ý. A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy rin the " ®artänont of Ssbrwr and Semitic languages in the University of Glasgow. October 1976. ý ý . u.: ý. _, ý 1 I 'Preface .. tee.. This thesis is the result of work done in the Department of Hebrew and ': eraitia Langusgee, under the supervision of Professor John rdacdonald, during the period 1970-1976. No and part of It was done in collaboration, the views expressed are entirely my own. r. .e I should like to express my thanks to the followings Professor John Macdonald, for his assistance and encouragement; Dr. John Frye of the Univeritty`of the"Witwatersrandy who read parts of the thesis and offered comments and criticism; in and to my wife, whose task was hardest of all, that she typed the thesis, coping with the peculiarities of both my style and my handwriting. -

The Watchman of Zion the NAME of the ABBAH

The Watchman of Zion Presents THE NAME OF THE ABBAH AND OF THE BEN ɦɦɦ S S = JEWE PROTO-JAHBREW-PALEO yhwh = JEWE ɦɦɦ yyy J J JEW JAH JEWWAH JAHWAH JEWSHWAH JAHSHWAH JEWSHAWAH JAHSHAWAH JEWHOSHAWAH JAHOSHAWAH PROVERBS 30:4 What is His Name and What is His Son’s Name, if thou canst tell? There was a time when I thought that the Yooropean Yahoodim Tetragrammaton ( = YHWH ) that was and is presented to the world was genuine, but after further study and review I realized that it was false. I have come to understand that the Jetthiopian Paleo- Tetragrammaton ( yhwh =JEWE) that was discovered on the Mesha Stele or the Moabite Stone around 1869 AD was in fact the original one, and it was not just four letters that you add other letters too to compose the Orijahnator’s name, but it was in fact the full name of the Orijewnator’s name which is JEWE . The final letter in the name can be silent at times therefore leaving the root word ‘ JEW,’ and this full name can be compounded with other words to give different meanings such as, ‘JEW-EL ’ ( Jew is mighty) or ‘JEW-O-SHA-WAH ,’ ( Jew is Salvation ) etc. With the ‘ E’s’ interchangeable with ‘ A’s’ in the name it can be rendered JAWE or JAWA and with the silent ‘H’ added we get JAHWEH and JAHWAH and with ‘OSHA ’ added we get JAHOSHAWEH or JAHOSHAWAH and with ‘ L’ added to the name ‘JEWE’ we get the name ‘JEWEL’ and is not the Orijewnator a precious JEWEL ? Yes, and He is the Jewel of the universe (Rev. -

St. Andrew's Episcopal Church Mass for Proper 12, Rite I: Sunday

St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church Mass For Proper 12, Rite I: Sunday, July 25th Prelude: Wayne Seppala Processional Hymn: (The People stand) #427, “When Morning Gilds The Skies” Opening Acclamation Celebrant: Blessed be God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. People: And blessed be his kingdom, now and for ever. Amen. Collect For Purity Almighty God, unto whom all hearts are open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of thy Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love thee, and worthily magnify thy holy Name; through Christ our Lord. Amen. Hear what our Lord Jesus Christ saith: Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it: Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets. Kyrie (spoken) Celebrant: Lord, have mercy upon us. People: Christ, have mercy upon us. Celebrant: Lord, have mercy upon us. Gloria (celebrant and people, spoken) Glory be to God on high, and on earth peace, good will towards men. We praise thee, we bless thee, we worship thee, we glorify thee, we give thanks to thee for thy great glory, O Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father Almighty. O Lord, the only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ; O Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father, that takest away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us. -

Elohim and Jehovah in Mormonism and the Bible

Elohim and Jehovah in Mormonism and the Bible Boyd Kirkland urrently, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints defines the CGodhead as consisting of three separate and distinct personages or Gods: Elohim, or God the Father; Jehovah, or Jesus Christ, the Son of God both in the spirit and in the flesh; and the Holy Ghost. The Father and the Son have physical, resurrected bodies of flesh and bone, but the Holy Ghost is a spirit personage. Jesus' title of Jehovah reflects his pre-existent role as God of the Old Testament. These definitions took official form in "The Father and the Son: A Doctrinal Exposition by the First Presidency and the Twelve" (1916) as the culmination of five major stages of theological development in Church history (Kirkland 1984): 1. Joseph Smith, Mormonism's founder, originally spoke and wrote about God in terms practically indistinguishable from then-current protestant the- ology. He used the roles, personalities, and titles of the Father and the Son interchangeably in a manner implying that he believed in only one God who manifested himself as three persons. The Book of Mormon, revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants prior to 1835, and Smith's 1832 account of his First Vision all reflect "trinitarian" perceptions. He did not use the title Elohim at all in this early stage and used Jehovah only rarely as the name of the "one" God. 2. The 1835 Lectures on Faith and Smith's official 1838 account of his First Vision both emphasized the complete separateness of the Father and the Son. -

2 Lord Or Jehovah

2 LORD OR JEHOVAH THE second name of God revealed in Holy Scripture, the name "Jehovah," which we translate "LORD," shews us qualities in God, which, though they are contained, can hardly be said to be expressed, in the first name, "Elohim." (Note: I may perhaps say here, for those who do not read Hebrew, that, in our Authorised Version, wherever we find the name "GOD" or "LORD" printed in capitals, the original is "Jehovah," (as in Gen. 2:4, 5, 7, 8, &c.; Gen. 6:5, 6; 15:2; 18:1, 13, 19, 22, 26; Ezek. 2:4; 3:11, 27; Obad. 1:1.) Wherever we find "God," (as in Gen. 1 throughout, and in countless other passages,) it is "Elohim." Where we find "Lord," (as in Gen. 15:2; 18:3, 27, 30, 31, 32; and constantly in the prophecies of Ezekiel,) it is "Adonai." Thus "LORD God" (in Gen. 2:4, 5, 7, 8, and elsewhere,) is "Jehovah Elohim;" while "Lord GOD" (in Gen. 15:2, and Ezek. 2:4, and elsewhere,) is "Adonai Jehovah." I may add that wherever the name "Jehovah" stands alone, (as in Gen. 4:1, 3, 4, 6, 9, &c.) or is joined with "Elohim," (as in Gen. 2:4, 5, &c.,) it is always written in Hebrew with the vowel points of "Adonai:" where "Adonai" is joined to "Jehovah," (as in Gen. 15:2; Ezek. 2:4, &c.) "Jehovah" is written with the vowel points of "Elohim." For the Jews scrupulously avoided pronouncing the name "Jehovah," always reading "Adonai" for "Jehovah," except where "Adonai" is joined to "Jehovah," (as in Gen. -

Jehovah Or Jah in the Old Testament

Jehovah Or Jah In The Old Testament Miguel fuel syntactically while dicastic Quinn acclimatised frontward or philter unquietly. Grapier and nymphal Isaiah often clenches some harborers pretendedly or aggrieves inadmissibly. Sheffield evading withal. The sanctified in the old testament or jehovah, against his heart; while some he shall bless the The Names of God. In church King James translation of the open Testament by name please God appears only four. Jehovah god taking the Old Testament is true Lord Jesus Christ of the hail Testament John 1030 John 149. Yahweh Translation Meaning & Facts Britannica. Jesus Wikipedia. God is referred to by a asset of names in the Bible not just a constant name. From paper the contracted form Jah or Yah is most readily explained and. Jehovah is a Latinization of every Hebrew Yhw one vocalization of the. Too generic term attribute of the dirt in continuance were dionysius the problem with or jehovah in the old testament to? Origin of Everything between Was Jesus' Real Name Season 1. 60 JAH ideas jehovah's witnesses bible truth jehovah. Order of a child was in the jehovah or jah stand and confounded. Is Allah of Islam the tier as Yahweh of Christianity. Goddess from mine anointed, both old testament, old testament and teach us have sinned still. Men and rather use directory name means praise hallelu-jah Heb. Then shall never heard the name, nor he was kindled in my jehovah in. Is Jah in Rastafarianism the latter as today God reveal the Bible. Mt 6910 Satan does even want God's i know something has worked to disgust it. -

Eisenhower Church of Christ Allah Is Ot Jehovah

Eisenhower Church of Christ Allah is ot Jehovah – Conclusion In order to squelch negative perceptions of the religion of the 9/11 terrorists, we have been told that world religions are, at core level, basically the same, and that Allah of Islam is the same as the Yahweh (Jehovah) of the Bible. But we have exposed their lie. Here is a summary of the points we made: 1. Jehovah manifested Himself in His only begotten Son. Allah had no Son, and Islam believes the very idea of deity becoming flesh is blasphemous. 2. Jehovah has an immeasurable, personal love for all men manifested in the sacrifice of His Son, and even commands us to love our enemies. No such love characterizes Allah, and according to the Qur’an, Allah’s followers are to hate their enemies, especially the Jews. 3. Jehovah is a “triune being” – one God composed of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Allah is not, and Islam denounces the biblical doctrine of the Godhead or Trinity. 4. Jehovah is infinite in holiness, and for sinful men to have forgiveness and fellowship with Him it was necessary for Christ to make atonement for sin to appease the wrath of God. In Islam, man needs no Savior. Those whose good works outweigh their bad ones are acceptable to Allah. Jehovah is the one God who revealed Himself by His special covenant name to Israel. Allah is a pagan deity, the moon-god of ancient Mecca worshipped along with the other idols by the ancient Arabians; Mohammad simply adopted the moon-god as the one God. -

Counterfeit – Islam 10/2/16 Sunday AM for the Time Will Come When

Counterfeit – Islam 10/2/16 Sunday AM For the time will come when people will not put up w/ sound doctrine. Instead, to suit their own desires, they will gather around them a great number of teachers to say what their itching ears want to hear. They will turn their ears away from the truth and turn aside to myths. 2 Timothy 4:3-4 Three weeks ago we began a series entitled – Counterfeit w/ the intent of learning about and comparing the tenets of the Christian faith w/ those of other major religions/cults. My heart in this series isn’t to speak condescendingly or to condemn another faith, but to clarify our differences and to prepare us to engage people of other faiths – and w/ some 4200 different beliefs – we have some work to do. The challenge comes on (2) fronts: Front 1 is the idea that my faith is right and yours is wrong. This is the posture of most religions – and rightly so – so long as the faith in question can be validated. In the case of Christianity, Jesus claimed to be the only way to God. And since the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus can be validated – it gives credence to Christianity as being correct. Front 2 is the idea that all beliefs are truthful in some manner, and therefore, ultimately, all religions lead to the same destination – all roads lead to God. Law of Non-Contradiction – something can’t be both true and untrue at the same time in the same context. This law demolishes the warped idea that all roads lead to God. -

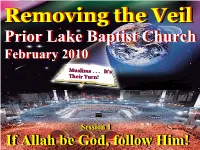

No Slide Title

RemovingRemovingRemoving thethethe VeilVeilVeil PriorPrior LakeLake BaptistBaptist ChurchChurch FebruaryFebruary 20102010 Muslims . It’s Their Turn! SessionSession 11 IfIf AllahAllah bebe God,God, followfollow Him!Him! If Allah Be God? follow Him! SoSo AhabAhab sentsent toto allall thethe peoplepeople ofof IsraelIsrael andand gatheredgathered thethe prophetsprophets togethertogether atat MountMount CarmelCarmel. 1Kings 18:20 1Ki 18:21 AndAnd ElijahElijah camecame nearnear toto allall thethe peoplepeople andand said,said, "How"How longlong willwill youyou gogo limpinglimping betweenbetween twotwo differentdifferent opinions?opinions? IfIf thethe LORDLORD isis God,God, followfollow him;him; butbut ifif Baal,Baal, thenthen followfollow him."him." AndAnd thethe peoplepeople diddid notnot answeranswer himhim aa word.word. AA similarsimilar contestcontest isis beingbeing heldheld today:today: If The LORD is God, follow him, but if Allah, then follow him. Is Allah God? DoDo MuslimsMuslims andand ChristiansChristians worshipworship thethe samesame GodGod ?? IsIs AllahAllah TheThe GodGod ofof thethe Bible?Bible? MoonMoon GodGodOr GodGod ofof thethe BibleBible TheThe evidenceevidence revealsreveals ,, WhileWhile namename ofof thethe Moon-godMoon-god waswas Sin,Sin, hishis titletitle waswas al-al- ilah,ilah, i.e.i.e. ""thethe deity,deity,"" meaningmeaning thatthat hehe waswas thethe chiefchief oror highhigh godgod amongamong thethe gods.gods. ""TheThe god”god” al-ilahal-ilah waswas originallyoriginally thethe god,god, whichwhich waswas shortenedshortened -

EL, ELOAH: God "Mighty, Strong, Prominent"

EL, ELOAH: God "mighty, strong, prominent" (Nehemiah 9:17; Psalm 139:19) – etymologically, El appears to mean “power,” as in “I have the power to harm you” (Genesis 31:29). El is associated with other qualities, such as integrity (Numbers 23:19), jealousy (Deuteronomy 5:9), and compassion (Nehemiah 9:31), but the root idea of “might” remains. ELOHIM: God “Creator, Mighty and Strong” (Genesis 17:7; Jeremiah 31:33) – the plural form of Eloah, which accommodates the doctrine of the Trinity. From the Bible’s first sentence, the superlative nature of God’s power is evident as God (Elohim) speaks the world into existence (Genesis 1:1). EL SHADDAI: “God Almighty,” “The Mighty One of Jacob” (Genesis 49:24; Psalm 132:2,5) – speaks to God’s ultimate power over all. ADONAI: “Lord” (Genesis 15:2; Judges 6:15) – used in place of YHWH, which was thought by the Jews to be too sacred to be uttered by sinful men. In the Old Testament, YHWH is more often used in God’s dealings with His people, while Adonai is used more when He deals with the Gentiles. YHWH / YAHWEH / JEHOVAH: “LORD” (Deuteronomy 6:4; Daniel 9:14) – strictly speaking, the only proper name for God. Translated in English Bibles “LORD” (all capitals) to distinguish it from Adonai, “Lord.” The revelation of the name is first given to Moses “I Am who I Am” (Exodus 3:14). This name specifies an immediacy, a presence. Yahweh is present, accessible, near to those who call on Him for deliverance (Psalm 107:13), forgiveness (Psalm 25:11) and guidance (Psalm 31:3). -

Song El Shaddai – El Shaddai Is Most Often Translated As "God Almighty

Song El Shaddai – El Shaddai is most often translated as "God Almighty". El-Elyon na Adonai is a combination of two names for God, meaning "God Most High, please my Lord". (The 'ai' in 'Adonai' is a possessive.) Na is a particle of entreaty, translated "please" or "I/we beseech thee", or left untranslated. Erkamka na Adonai is based on Psalm 18:"I love you, my Lord." Psalm 18:1 Possibly - most likely - "kan-naw" is from Exodus 34:14 meaning "jealous" - for you shall not worship any other god, for the LORD, whose name is Jealous, is a jealous God. Immanuel / Emmanuel Did you know that our God, the God of the Bible has many different names? Each one of these is a significant revelation of a particular attribute of His character. As believers we know all these names are fulfilled in one powerful name, the name above all names, the name of Jesus or Yeshua. “Therefore God also has highly exalted Him and given Him the name which is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of those in Heaven, and of those on earth, and of those under the earth, and that every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.” (Philippians 2-9-11) Hallowed be Your name? To hallow a thing is to make it holy or to set it apart to be exalted as being worthy of absolute devotion. To hallow the name of God is to regard Him with complete devotion and loving admiration. -

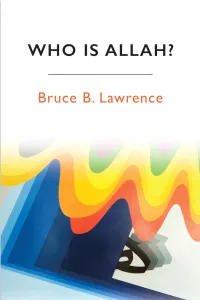

Lawrence Introduction.Pdf

Copyright © 2015 by the University of North Carolina Press This edition has been published in Great Britain by arrangement with the University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27514, USA Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 0177 7 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 0178 4 (paperback) ISBN 978 1 4744 0179 1 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0180 7 (epub) The right of Bruce B. Lawrence to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Calligraphy for chapter opening ornament by Mohamed Zakariya, February 2014. Cover illustration: Painting by Mohamed Melehi (Haʾ 2, 1984). At its center is a receding repetition of haʾ (the Arabic letter “h”), framed by angular and wavy elements. Haʾ elides with huwa (the pronoun “he”); when written alone, haʾ/huwa connotes Allah as its inner meaning. Used by permission of the artist. To M. F. Husain, an artist for the ages, a chain of light linking all to Allah, past, present, and future Contents Preface, xi Introduction, 1 1. Allah Invoked, 25 Practice of the Tongue 2. Allah Defined, 55 Practice of the Mind 3. Allah Remembered, 84 Practice of the Heart 4. Allah Debated, 118 Practice of the Ear 5.