Arms & Armor of the Pilgrims

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

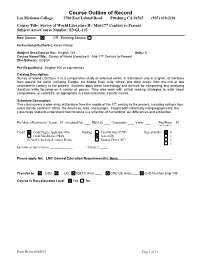

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

Duxbury's First Settlers Were Mayflower Passengers

Duxbury’s first settlers were Mayflower passengers... “…the people of the Plantation began to grow in their outward estates…and no man thought he could live, except he had cattle and a great deal of ground to keep them, all striving to increase their stocks. By which means, they were scattered all over the bay quickly.” William Bradford, Of Plimoth Plantation. In 1627, seven years after their arrival, Myles Standish, William Bradford, Elder Brewster, John Alden and other Plymouth leaders called “Undertakers” had assumed the debt owed their investors and moved to an area ultimately incorporated in 1637 as Duxbury. As families started to leave Plymouth in the land division of 1627 each member was allotted 20 acres to create a family farm with lots starting at the water’s edge. Duxbury’s earliest economic beginnings started the American dream of land ownership. Its exports suppled corn, timber and commodities to Boston’s Winthrop migration in the 1630s. Coasters like John Alden and John How- land established coastal fur trading with Native Americans in Maine. They traded and shipped fur pelts back to England to be used for felt which was the fabric of the garment industry at that time in history. Leading up to 2020, Duxbury has joined with other regional Pilgrim related historic sites to commemorate the 400th Mayflower Journey and Plymouth Settlement. Future Duxbury was first explored from Clark’s Island. Before landing in Plymouth, the Mayflower anchored off Provincetown and a scouting party in a smaller boat set sail to explore what is now Cape Cod Bay. -

Staff Working Paper No. 845 Eight Centuries of Global Real Interest Rates, R-G, and the ‘Suprasecular’ Decline, 1311–2018 Paul Schmelzing

CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 -

On-Site Historical Reenactment As Historiographic Operation at Plimoth Plantation

Fall2002 107 Recreation and Re-Creation: On-Site Historical Reenactment as Historiographic Operation at Plimoth Plantation Scott Magelssen Plimoth Plantation, a Massachusetts living history museum depicting the year 1627 in Plymouth Colony, advertises itself as a place where "history comes alive." The site uses costumed Pilgrims, who speak to visitors in a first-person presentvoice, in order to create a total living environment. Reenactment practices like this offer possibilities to teach history in a dynamic manner by immersing visitors in a space that allows them to suspend disbelief and encounter museum exhibits on an affective level. However, whether or not history actually "comes alive"at Plimoth Plantation needs to be addressed, especially in the face of new or postmodem historiography. No longer is it so simple to say the past can "come alive," given that in the last thirty years it has been shown that the "past" is contestable. A case in point, I argue, is the portrayal of Wampanoag Natives at Plimoth Plantation's "Hobbamock's Homesite." Here, the Native Wampanoag Interpretation Program refuses tojoin their Pilgrim counterparts in using first person interpretation, choosing instead to address visitors in their own voices. For the Native Interpreters, speaking in seventeenth-century voices would disallow presentationoftheir own accounts ofthe way colonists treated native peoples after 1627. Yet, from what I have learned in recent interviews with Plimoth's Public Relations Department, plans are underway to address the disparity in interpretive modes between the Pilgrim Village and Hobbamock's Homesite by introducing first person programming in the latter. I Coming from a theatre history and theory background, and looking back on three years of research at Plimoth and other living history museums, I would like to trouble this attempt to smooth over the differences between the two sites. -

Epic of Saltpetre to Gunpowder

Indian Journal of History of Science, 40.4 (2005) 539-57 1 EPIC OF SALTPETRE TO GUNPOWDER (Received 17 March 2005) The article provides a very tentative contour of an epic which is yet to be written in completeness, even several details of which may not have been yet discovered. Whereas the development of the nuclear weapons has taken only a few decades of the 20th century, the epic of the development of saltpetre to gunpowder, and the associated knowledge proliferation across many countries, spanned over many centuries, in fact more than a millen- nium. The Chinese origin of this epic (with a faint Indian link) is more or less established. The story of guns and other firearms is outside the scope of this article. This dissertation highlights the contributions of eminent scholars like Needham, Sarton, Gode and lqtidar Alam Khan, and also emphasizes the cross-currents of the progress and clash of civilizations, as the grand saga went on unfolding itself over the ages. History of armament research and development inevitably ushers in the philosophical issue of ends and means in the human civilization. Key Words: Chinese gunpowder tradition, Firearms, Gunpowder, Indian gunpowder tradition, Pyrotechnics, Saltpetre, Transmission, Technical terms - Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Turkish, Urdu. The spirit of human civilization has never endorsed 'violence', and yet has encountered violence from the Nature, the animal world and diverse and hostile human traditions as facts of life, to be resisted by scientific knowledge and technological innovations. The knowledge regarding fire and its applica- tions, some of them catastrophic, cannot be unlearnt, even for the sake of the high ideals of peace and non-violence. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Baltic Towns030306

Seventeenth Century Baltic Merchants is one of the most frequented waters in the world - if not the Tmost frequented – and has been so for the last thousand years. Shipping and trade routes over the Baltic Sea have a long tradition. During the Middle Ages the Hanseatic League dominated trade in the Baltic region. When the German Hansa definitely lost its position in the sixteenth century, other actors started struggling for the control of the Baltic Sea and, above all, its port towns. Among those coun- tries were, for example, Russia, Poland, Denmark and Sweden. Since Finland was a part of the Swedish realm, ”the eastern half of the realm”, Sweden held positions on both the east and west coasts. From 1561, when the town of Reval and adjacent areas sought protection under the Swedish Crown, ex- pansion began along the southeastern and southern coasts of the Baltic. By the end of the Thirty Years War in 1648, Sweden had gained control and was the dom- inating great power of the Baltic Sea region. When the Danish areas in the south- ern part of the Scandinavian Peninsula were taken in 1660, Sweden’s policies were fulfilled. Until the fall of Sweden’s Great Power status in 1718, the realm kept, if not the objective ”Dominium Maris Baltici” so at least ”Mare Clausum”. 1 The strong military and political position did not, however, correspond with an economic dominance. Michael Roberts has declared that Sweden’s control of the Baltic after 1681 was ultimately dependent on the good will of the maritime powers, whose interests Sweden could not afford to ignore.2 In financing the wars, the Swedish government frequently used loans from Dutch and German merchants.3 Moreover, the strong expansion of the Swedish mining industries 1 Rystad, Göran: Dominium Maris Baltici – dröm och verklighet /Mare nostrum. -

"Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? by BRIDGET WALKER

Intro to Late Period "Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? BY BRIDGET WALKER An Allegory of Autumn by Lucas Van Valkenborch Grietje Pietersdr Codde by Adriaen (1535-1597) Thomasz. Key, 1586 Where Are We Again? This is the coast of modern day Belgium and The Netherlands, with the east coast of England included for scale. According to Fynes Moryson, an Englishman traveling through the area in the 1590s, the cities of Bruges and Ghent are in Flanders, the city of Antwerp belongs to the Dutchy of the Brabant, and the city of Amsterdam is in South Holland. However, he explains, Ghent and Bruges were the major trading centers in the early 1500s. Consequently, foreigners often refer to the entire area as "Flemish". Antwerp is approximately fifty miles from Bruges and a hundred miles from Amsterdam. Hairstyles The Cook by PieterAertsen, 1559 Market Scene by Pieter Aertsen Upper class women rarely have their portraits painted without their headdresses. Luckily, Antwerp's many genre paintings can give us a clue. The hair is put up in what is most likely a form of hair taping. In the example on the left, the braids might be simply wrapped around the head. However, the woman on the right has her braids too far back for that. They must be sewn or pinned on. The hair at the front is occasionally padded in rolls out over the temples, but is much more likely to remain close to the head. At the end of the 1600s, when the French and English often dressed the hair over the forehead, the ladies of the Netherlands continued to pull their hair back smoothly. -

Nicholas Victor Sekunda the SARISSA

ACTA UNI VERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA ARCHAEOLOGICA 23, 2001 Nicholas Victor Sekunda THE SARISSA INTRODUCTION Recent years have seen renewed interest in Philip and Alexander, not least in the sphere of military affairs. The most complete discussion of the sarissa, or pike, the standard weapon of Macedonian footsoldiers from the reign of Philip onwards, is that of Lammert. Lammert collects the ancient literary evidence and there is little one can disagree with in his discussion of the nature and use of the sarissa. The ancient texts, however, concentrate on the most remarkable feature of the weapon - its great length. Unfor- tunately several details of the weapon remain unclear. More recent discussions o f the weapon have tried to resolve these problems, but I find myself unable to agree with many of the solutions proposed. The purpose of this article is to suggest some alternative possibilities using further ancient literary evidence and also comparisons with pikes used in other periods of history. 1 do not intend to cover those aspects of the sarissa already dealt with satisfactorily by Lammert and his predecessors'. THE PIKE-HEAD Although the length of the pike is the most striking feature of the weapon, it is not the sole distinguishing characteristic. What also distinguishes a pike from a common spear is the nature of the head. Most spears have a relatively broad head designed to open a wide flesh wound and to sever blood vessels. 1 hey are usually used to strike at the unprotected parts of an opponent’s body. The pike, on the other hand, is designed to penetrate body defences such as shields or armour. -

Puritan New England: Plymouth

Puritan New England: Plymouth A New England for Puritans The second major area to be colonized by the English in the first half of the 17th century, New England, differed markedly in its founding principles from the commercially oriented Chesapeake tobacco colonies. Settled largely by waves of Puritan families in the 1630s, New England had a religious orientation from the start. In England, reform-minded men and women had been calling for greater changes to the English national church since the 1580s. These reformers, who followed the teachings of John Calvin and other Protestant reformers, were called Puritans because of their insistence on purifying the Church of England of what they believed to be unscriptural, Catholic elements that lingered in its institutions and practices. Many who provided leadership in early New England were educated ministers who had studied at Cambridge or Oxford but who, because they had questioned the practices of the Church of England, had been deprived of careers by the king and his officials in an effort to silence all dissenting voices. Other Puritan leaders, such as the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop, came from the privileged class of English gentry. These well-to-do Puritans and many thousands more left their English homes not to establish a land of religious freedom, but to practice their own religion without persecution. Puritan New England offered them the opportunity to live as they believed the Bible demanded. In their “New” England, they set out to create a model of reformed Protestantism, a new English Israel. The conflict generated by Puritanism had divided English society because the Puritans demanded reforms that undermined the traditional festive culture. -

Ming China As a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2018 Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duan, Weicong, "Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1719. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Dissertation Examination Committee: Steven B. Miles, Chair Christine Johnson Peter Kastor Zhao Ma Hayrettin Yücesoy Ming China as a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 by Weicong Duan A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 St. Louis, Missouri © 2018, -

Tinker Emporium Tinker Emporium Vol. Firearms Vol. 7

Tinker Emporium Vol. 7 Firearms Introduction : This file contains ten homebrew firearms (based on real world) , each presented with a unique description and a colored picture. Separate pictures in better resolution are included in the download for sake of creating handouts, etc. by Revlis M. Template Created by William Tian DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D& D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Co ast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any re production or unauthorized use of the mater ial or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast. ©2018 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057 -0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 SampleThe Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, file Not for resale. Permission granted to print or photocopy this document for personal use only . T.E. Firearms 1 Firearms Fire L ance Introduction and Points of Interest Firearm, 5 lb, Two-handed, (2d4) Bludgeoning, Ranged (15/30), Reload, Blaze Rod What are Firearms in D&D Firearms by definition are barreled ranged weapons that inflict damage by launching projectiles. In the world of D&D the firearms are created with the use of rare metals and alchemical discoveries.