The Uses of Fig (Ficus) by Five Ethnic Minority Communities in Southern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MYANMAR Full Moon Festival, Temples and Waterways

MYANMAR Full Moon Festival, Temples and Waterways Dates: Dec. 29, 2017—Jan. 10, 2018 Cost: $3,450 (Double Occupancy) Explore the rich cultural depths of this little known country from Buddhist temples to fishing communities, with the highlight of the Full Moon Festival in Bagan. !1 ! ! ! Daily Itinerary Rooted in history and rich in culture, Myanmar (formerly known as Burma) is a country filled with awe inspiring Buddhist temples and British colonial structures. The diversity of the local people can be seen with the traditional one legged fishing style on Lake Inle to the rituals of the pilgrims at the Shwedagon Pagoda. We will traverse this magnificent country, starting in the south at Yangon, and hopping to the banks of the Ayeyarwady River in Bagan for an unmatchable experience. Bagan will be the site of the Full Moon Festival where we will participate in the festivities and sample the local dishes. Then we set out on Lake Inle to see the fisherman, floating gardens and a variety of wildlife. The trip concludes in the northern city of Mandalay for once last adventure in this captivating country. Day 1 | Friday, December 29 | Yangon Upon midday arrival in Yangon, your local guide will meet and transfer you to the hotel. Once you have a chance to settle in, there will be a group orientation and an invitation to a traditional welcome dinner at the hotel. Grand United Hotel (Ahlone Branch) (D) YANGON (formerly Rangoon) is the former capital of Myanmar and largest city with nearly 7 million inhabitants. The center of political and economic power under British colonial rule, it still boasts a unique mixture of modern buildings and traditional wooden structures with numerous parks, it was known as the “Garden of the East”. -

4-Day Inle Lake and Kakku Discovery

4-Day Inle Lake and Kakku Discovery Downloaded on: 23 Sep 2021 Tour code: PKHCIKDB Tour type ( Private ) Tour Level: Relaxed / Easy Tour Comfort: Standard Tour Period: 4 Days English Heho, Inle Lake, Taunggyi, Kakku highlights tour details Full day boat tour to Indaing to see 14th -18th century pagodas During these 4 Days, explore the fascinating Inle lake and its Explore the 5-day rotating markets surrounding. You will visit the Kakku Pagoda complex near Taunggyi Visit Phaung Daw Oo Pagoda and surroundings which features a cluster of fantastic ancient monuments and is Learn how to make traditional handicrafts located in the heart of the Pao Territory. On the way up or down, stop silk weaving in local workshop in Taunggyi to visit the local market. On other days, visit the main Drive to Kakku via Taunggyi to visit a fascinating range of pagodas sites on the lake going along the floating gardens and the houses on in the Pa-O territory stilts. The fishermen and their unique way of rowing (leg rowers) are of particular interest. why choose this tour? A perfect opportunity to explore fascinating Inle Lake and its surrounding charming areas Discovering the historical background and finest architecture at Kakkku Pagodas Complex in Pa-O region Meeting with the inspiring locals aritsans to observe their traditional techniques and rural ways of life Contact [email protected] www.diethelmtravel.com Copyright © Diethelm Travel Management Limited. All right reserved. 4-Day Inle Lake and Kakku Discovery Contact [email protected] www.diethelmtravel.com Copyright © Diethelm Travel Management Limited. -

Assistance for Ethnic Minorities in Myanmar Through ODA (PDF, 312KB)

Chapter 1: ODA for Moving Forward Together Section 1: ODA for Achieving a Free, Prosperous, and Stable International Community – Assistance for democratization and national reconciliation Part I ch.1 ODA Assistance for Ethnic Minorities Topics in Myanmar through ODA ■ Surrounding ethnic minorities issues towards national reconciliation, including the peace process with ethnic minorities. Promoting regional development and Myanmar is said to be home to 135 different ethnic groups. the consolidation of peace, Japan will proactively implement Of these, the Bamar occupy about 70% of the population, assistance in ethnic minorities’ areas in order to contribute to living mainly in the central plains region. The ethnic the stable and sustainable growth of Myanmar. minorities that account for the remaining 30% primarily live Japan has thus far implemented assistance for ethnic in the mountainous regions near national borders. These minority regions based on the issues and needs of each state, minorities are broadly divided into seven major national focusing its support in the area of agriculture, which is their races, which are: Kachin, Kayah (Karenni), Karen (Kayin), primary industry. Chin, Mon, Shan, and Rakhine (Arakan). The races are To name a few, rural development assistance (technical further broken down into 134 ethnic groups. cooperation) has been provided in the northern area of Shan The issues surrounding ethnic minorities in Myanmar are State for the dissemination and distribution of drug crop deeply rooted and were caused by the “divide and rule” alternatives. In the southern part of Shan State, production administration during British colonial period. Even after and distribution assistance in the development of sustainable gaining independence in 1948, conflict between the national circular agriculture was provided by working with NPO military and ethnic armed groups continued for 60 years in Terra People Association on a technical cooperation. -

VISIBILITY VERSUS VULNERABILITY: Understanding Instability and Opportunity in Myanmar

VISIBILITY VERSUS VULNERABILITY: understanding instability and opportunity in Myanmar Visibility versus Vulnerability: Understanding Instability and Opportunity in Myanmar Table of Content Executive Summary . 2 Background . 4 Methodology . 5 Main Findings . 5 I . Visibility Versus Vulnerability: The Shape of Conflict . 5 A . Community Capacity to Negotiate Change . 6 B . Land Usage and Tenure . 6 C . Competing Economic and Environmental Priorities . 8 D . New People, New Problems and Opportunities . 9 E . Government Decentralization and Disengagement . 9 F . Civil Society’s Evolving Roles . 10 G . Youth Power and Potential . 11 II . Looking Forward and Building Momentum . 11 A . Build Community Cohesion . 11 B . Strengthen the Social Contract Between the Government and People . 12 C . Promote Internal Government Coordination . 13 D . Invest in the Economic Stability of Individuals and Communities . 14 Next Steps . 15 Annex 1: . 16 The Administrative Structure for Shan State . 16 Background Information . 16 Annex 2: . 18 Land Registration Policies and Procedures . 18 Acknowledgements: Thank you to the many people who made this assessment possible, including Jenny Vaughan, Su Phyo Lwin, Evelyn Ko Than, Thein Zaw, Nilan Fernando and individuals from the government, local cultural and non-governmental organizations and the local community who were willing to share both their time and their insights with the assessment team. Special thanks to Ruth Allen and Bree Oswill for reviewing and proof reading the report. Sanjay Gurung, Senior Technical Advisor, Resilience, Governance and Partnership Sasha Muench, Director of Economic and Market Development Jessica Wattman, Senior Technical Advisor, Youth and Conflict Management May 2014 mercycorps.org < Table of Contents 1 Visibility versus Vulnerability: Understanding Instability and Opportunity in Myanmar Executive Summary Myanmar is changing. -

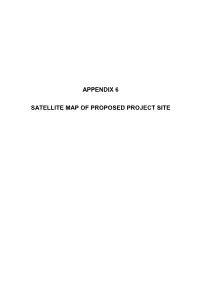

Appendix 6 Satellite Map of Proposed Project Site

APPENDIX 6 SATELLITE MAP OF PROPOSED PROJECT SITE Hakha Township, Rim pi Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village A6-1 Falam Township, Webula Village Tract, Chin State Kim Mon Chaung Village A6-2 Webula Village Pa Mun Chaung Village Tedim Township, Dolluang Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village Dolluang Village A6-3 Taunggyi Township, Kyauk Ni Village Tract, Shan State A6-4 Kalaw Township, Myin Ma Hti Village Tract and Baw Nin Village Tract, Shan State A6-5 Ywangan Township, Sat Chan Village Tract, Shan State A6-6 Pinlaung Township, Paw Yar Village Tract, Shan State A6-7 Symbol Water Supply Facility Well Development by the Procurement of Drilling Rig Nansang Township, Mat Mon Mun Village Tract, Shan State A6-8 Nansang Township, Hai Nar Gyi Village Tract, Shan State A6-9 Hopong Township, Nam Hkok Village Tract, Shan State A6-10 Hopong Township, Pawng Lin Village Tract, Shan State A6-11 Myaungmya Township, Moke Soe Kwin Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-12 Myaungmya Township, Shan Yae Kyaw Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-13 Labutta Township, Thin Gan Gyi Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Protection Dike Rainwater Pond (New) : 5 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) : 20 Facilities A6-14 Labutta Township, Laput Pyay Lae Pyauk Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-15 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Irrigation Channel Rainwater Pond (New) : 2 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) Hinthada Township, Tha Si Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-16 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road -

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

Legends of the Golden Land the Road

The University of North Carolina General Alumni Association LLegendsegends ooff thethe GGoldenolden LLandand aandnd tthehe RRoadoad ttoo MMandalayandalay with UNC’s Peter A. Coclanis February 10 to 22, 2014 ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Dear Carolina Alumni and Friends: Myanmar, better known as Burma, has recently re-emerged from isolation after spending decades locked away from the world. Join fellow Tar Heels and friends and be among the fi rst Americans to experience this golden land of deeply spiritual Buddhist beliefs, old world traditions and more than one million pagodas. You will become immersed in the country’s rich heritage, the incredible beauty of its landscape and the warmth of friendly people who take great pride in welcoming you to their ancient and enchanting land. Breathtaking moments await you amid the lush greenery and golden plains as you discover great kingdoms that have risen and fallen through thousands of years of history. See the legacy of Britain’s former colony in its architecture and tree-lined boulevards, and the infl uences of China, India and Thailand evident in the art, dance and dress of Myanmar today. Observe and interact with skilled artisans who practice the traditional arts of textile weaving, goldsmithing, lacquerware and wood carving. Meet fascinating people, local experts and musicians who will enhance your experience with educational lectures and insightful presentations. And, along the streets and in the markets you will sense the metta bhavana, the culture of loving kindness that the Burmese extend to you, their special guest. This comprehensive itinerary features colonial Yangon, the archaeological sites of Bagan, the palace of Mandalay and the exquisite Inle Lake, with forays along the fabled Irrawaddy River. -

Report on "Youth Perceptions of Pluralism and Diversity in Yangon

YOUTH PERCEPTIONS OF PLURALISM AND DIVERSITY IN YANGON, MYANMAR Report prepared for UNESCO by Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) 22 November 2019 Yangon, Myanmar YOUTH PERCEPTIONS OF PLURALISM AND DIVERSITY IN YANGON, MYANMAR Executive summary 3 Introduction 5 Literature Review 6 Education 6 Isolation and Public and Cultural Spaces 6 Religion and Ethnicity 7 Histories and Memories of Coexistence, Friendship, and Acceptance 7 Discrimination and Burmanization 7 Parents, Teachers, and Lessons: Hierarchy and Social Norms 8 Social Media 8 Methodology 10 Ethnic and Religious Communities 11 Research Findings 13 Perceptions of Cultural Diversity, Pluralism and Tolerance 13 Discrimination, Civil Documentation and Conflict 15 Case Study 17 Socialization: Parents, Peers, and Lessons 19 Proverbs, Idioms, Mottos 19 Peers and Friends 20 Parents and Elders 21 Education (Schools, Universities and Teachers) 22 Isolation and Space 26 Festivals, Holidays, and Cultural and Religious Sites 27 Civic and Political Participation 29 Social Media and Hate Speech 30 Employment and Migration 31 Language 32 Change Agents 33 Conclusion 35 Recommendations for Program Expansion 37 Civil Society Mapping 38 References 41 2 YOUTH PERCEPTIONS OF PLURALISM AND DIVERSITY IN YANGON, MYANMAR Executive summary A number of primary gaps have been identified in the existing English language literature on youth, diversity, and pluralism in Myanmar that have particular ramifications for organizations and donors working in the youth and pluralism space. The first is the issue of translation. Most of the existing literature makes no note of how concepts such as diversity, tolerance, pluralism and discrimination are translated into Burmese or if there is a pre-existing Burmese concept or framework for these concepts, and particularly, how youth are using and learning about these concepts. -

Islamic Education in Myanmar: a Case Study

10: Islamic education in Myanmar: a case study Mohammed Mohiyuddin Mohammed Sulaiman Introduction `Islam', which literally means `peace' in Arabic, has been transformed into a faith interpreted loosely by one group and understood conservatively by another, making it seem as if Islam itself is not well comprehended by its followers. Today, it is the faith of 1.2 billion people across the world; Asia is a home for 60 per cent of these adherents, with Muslims forming an absolute majority in 11 countries (Selth 2003:5). Since the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, international scholars have become increasingly interested in Islam and in Muslims in South-East Asia, where more than 230 million Muslims live (Mutalib 2005:50). These South-East Asian Muslims originally received Islam from Arab traders. History reveals the Arabs as sea-loving people who voyaged around the Indian Ocean (IIAS 2005), including to South-East Asia. The arrival of Arabs has had different degrees of impact on different communities in the region. We find, however, that not much research has been done by today's Arabs on the Arab±South-East Asian connection, as they consider South-East Asia a part of the wider `East', which includes Iran, Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Indeed, the term `South-East Asia' is hardly used in modern Arab literature. For them, anything east of the Middle East and non-Arabic speaking world is considered to be `Asia' (Abaza 2002). According to Myanmar and non-Myanmar sources, Islam reached the shores of Myanmar's Arakan (Rakhine State) as early as 712 AD, via oceangoing merchants, and in the form of Sufism. -

Ethnobotanical Study on Wild Edible Plants Used by Three Trans-Boundary Ethnic Groups in Jiangcheng County, Pu’Er, Southwest China

Ethnobotanical study on wild edible plants used by three trans-boundary ethnic groups in Jiangcheng County, Pu’er, Southwest China Yilin Cao Agriculture Service Center, Zhengdong Township, Pu'er City, Yunnan China ren li ( [email protected] ) Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0810-0359 Shishun Zhou Shoutheast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences & Center for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences Liang Song Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences & Center for Intergrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences Ruichang Quan Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences & Center for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences Huabin Hu CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences Research Keywords: wild edible plants, trans-boundary ethnic groups, traditional knowledge, conservation and sustainable use, Jiangcheng County Posted Date: September 29th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-40805/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on October 27th, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00420-1. Page 1/35 Abstract Background: Dai, Hani, and Yao people, in the trans-boundary region between China, Laos, and Vietnam, have gathered plentiful traditional knowledge about wild edible plants during their long history of understanding and using natural resources. The ecologically rich environment and the multi-ethnic integration provide a valuable foundation and driving force for high biodiversity and cultural diversity in this region. -

5-Year Strategic Development Plan, 2018-2022 Pa-O Self-Administered Zone Shan State, Republic of the Union of Myanmar

5-Year Strategic Development Plan, 2018-2022 Pa-O Self-Administered Zone Shan State, Republic of the Union of Myanmar A PROSPEROUS COMMUNITY FOR THIS AND FUTURE VOLUME II: DEVELOPMENT PROPOSALS GENERATIONS Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development 12, Kanbawza Street, Bahan Township Yangon, Myanmar [email protected] | www.mmiid.org Author | Paul Knipe Contributors | Victoria Garcia, Mike Haynes, U Yae Htut, Qingrui Huang, Jolanda Jonkhart, Joern Kristensen, Daw Khin Yupar Kyaw, U Ko Lwin, Daw Hsu Myat Myint Lwin, U Myint Lwin, Daw Thet Htar Myint, U Nay Linn Oo, Samuel Pursch, Barbara Schott, Dr Khin Thawda Shein, U Kyaw Thein, Daw Nilar Win Yangon, August 2018 Cover image | Participant from the Pa-O Women’s Union at the Evaluation and Strategy Workshop TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations .........................................................................................................................I Map of the Pa-O SAZ ..........................................................................................................II Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1 1. Infrastructure ...................................................................................................................2 Map 1: Hopong Township village road upgrade ...................................................3 Map 2: Hsihseng Township village road upgrade ................................................4 Map 3: Pinlaung Township village road upgrade .................................................5 -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census.