Evaluation of FAO Cooperation in Sierra Leone 2001 – 2006. Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System

Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System Bombali/Sierra Leone First Bimonthly Report September 2016 Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System Report—SIAPS/Sierra Leone, September 2016 This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00021. The contents are the responsibility of Management Sciences for Health and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. About SIAPS The goal of the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program is to ensure the availability of quality pharmaceutical products and effective pharmaceutical services to achieve desired health outcomes. Toward this end, the SIAPS results areas include improving governance, building capacity for pharmaceutical management and services, addressing information needed for decision-making in the pharmaceutical sector, strengthening financing strategies and mechanisms to improve access to medicines, and increasing quality pharmaceutical services. Recommended Citation This report may be reproduced if credit is given to SIAPS. Please use the following citation. Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System Report Bombali/ Sierra Leone, September 2016. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health. Key Words Sierra Leone, Bombali, Continuous Results Monitoring and Support System (CRMS) Report Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services Pharmaceuticals and Health Technologies Group Management Sciences for Health 4301 North Fairfax Drive, Suite 400 Arlington, VA 22203 USA Telephone: 703.524.6575 Fax: 703.524.7898 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.siapsprogram.org ii CONTENTS Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................... -

Northern Province

SIERRA LEONE NORTHERN PROVINCE Chiefdom Geo Codes Geo Code Name Bombali 45 Bombali Shebora 46 Makari Gbanti 47 Paki Masabong Banguraya 48 Leibasgayahun Kamagbungban I ! ! Bantahun Dembelia Sinkunia ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Kafaren ! ! P!etewoh ! Soriya ! ! Kidoia ! 49 Sanda Tendaren ! Kaso! ria ! !! ! Alagiya !! !! Upk!osay Kor!os ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Dogoto ! !! ! ! K!um! a! i ! ! Purikoh ! Sabuya ! !! Kaliere ! ! Wambaya ! ! ! Gib!iya ! ! ! ! Kanaya 50 Magbaiamba Ngowahua K! abetor Kasongo Ganya ! ! ! N'J!ura ! ! ! ! ! ! Bo! ntola ! ! Fre! nken ! )"! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Gbankan Ferenya ! ! Taelia ! ! ! ! ! Makaia ! !! Sungbaya ! Karibum ! ! 51 Gbanti Kamaranka Kabruma Dufe Yonkaya Dare-Salam ! ! ! ! Tanduia ! ! ! ! Kabaia Gobu Defe Kambitambaia ! ! Dansaia Kagbokoso ! ! Kalia ! ! ! ! !! ! Yolaia !! ! 52 Sanda Loko ! ! Sankan ! ! ! ! Ganya! Ganya Mak!aya Kamadolay ! Y! enke ! ! ! !! Karifaya !! ! K! akan!ara Selie I ! ! Cawuya ! ! Was!sa I !! Soy! a ! 53 Sella Limba ! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!! ! ! Nimebadi ! Sere Kude !! Koffin !!!! Gulusaya ! ! ! ! Kolon ! ! Modia ! Kawulia ! ! ! ! Bindiya ! ! 54 Tambakka ! ! Morikalia ! ! ! ! ! Gbind!i I ! Kobalia ! Wassa ! Yawuya ! Nyakasa ! ! ! Kak!opra ! ! ! Kamanday ! ! ! ! ! Duraia ! Salifuia ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! Sobila 55 Gbendembu Ngowahun Ko!tti ! Fosia ! ! ! ! M! omi ! 5 Kasella ! Gor!eh Lakatha Malanga Yanga I Kumiya ! Kodandain ! !! ! s Yenkisa I Nu!m!uma I Kimbilie Kambaidi 56 Safroko Limba ! ! ! ! Kunbuluya Tum!aniya! ! ! ! Foyae Dumbaia Dandaia e !! ! -

Emis Code Council Chiefdom Ward Location School Name

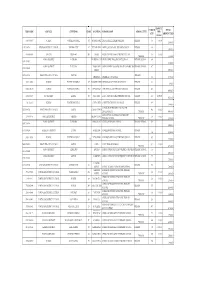

AMOUNT ENROLM TOTAL EMIS CODE COUNCIL CHIEFDOM WARD LOCATION SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL LEVEL PER ENT AMOUNT PAID CHILD 5103-2-09037 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 391 ROGBANGBA ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRIMARY PRIMARY 369 10,000 3,690,000 1291-2-00714 KENEMA DISTRICT COUNCIL KENEMA CITY 67 FULAWAHUN ABDUL JALIL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 380 3,800,000 4114-2-06856 BO CITY TIKONKO 289 SAMIE ABDUL TAWAB HAIKAL PRIMARY SCHOOL 610 10,000 PRIMARY 6,100,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO DOWN BALLOP ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 694 1391-2-02007 6,940,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO TAMBA ABU ABDULAI IBNU MASSOUD ANSARUL ISLAMIC MISPRIMARY SCHOOL 407 1391-2-02009 STREET 4,070,000 5208-2-10866 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL WEST III PRIMARY ABERDEEN ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL 366 3,660,000 5103-2-09002 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 397 KOSSOH TOWN ABIDING GRACE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 62 620,000 5103-2-08963 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 373 BENGUEMA ABNAWEE ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOOL PRIMARY 405 4,050,000 4109-2-06695 BO DISTRICT KAKUA 303 KPETEMA ACEF / MOUNT HORED PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 411 10,000.00 4,110,000 Not found WARDC WATERLOO RURAL COLE TOWN ACHIEVERS PRIMARY TUTORAGE PRIMARY 388 3,880,000 ACTION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 5205-2-09766 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL EAST III CALABA TOWN 460 10,000 DEVELOPMENT PRIMARY 4,600,000 ADA GORVIE MEMORIAL PREPARATORY 320401214 BONTHE DISTRICT IMPERRI MORIBA TOWN 320 10,000 PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 3,200,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO BONGALOW ADULLAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 323 1391-2-01954 3,230,000 1109-2-00266 KAILAHUN DISTRICT LUAWA KAILAHUN ADULLAM PRIMARY -

Addax Bioenergy Sierra Leone. an Assemblage of a Large Scale Land

Institute of Geography of the University of Bern! Master Thesis! Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Stephan Rist! ! Addax Bioenergy Sierra Leone! ! Analysis of the implementation process of a large scale land acquisition project from the perspective of assemblage theory! ! ! ! Samuel M. Lustenberger ! 09-203-183! [email protected]! 30.03.2015 Abstract! ! This thesis presents an analysis of the implementation process of the Addax Bioenergy project in Sierra Leone from the perspective of assemblage theory. It seeks to contribute to an ongoing debate about Large Scale Land acquisition in countries of the Global South. The case study addresses research questions about the preconditions, the concrete implementation and occurring counteracting processes of such a project. The findings are based on a set of qualitative methods applied during a 4 months field stay in Sierra Leone from August until December 2013.! Five important elements are identified that enabled the coming into being of the Addax Bioenergy project: The mother company AOG, the Biofuel Complex, the European Union, Development Finance Institutions and Sierra Leone as the place of operation.! They were linked together by a social network of people with the right skills, connections or positions in a complex process that took place over several years. A range of factors that were working against the formation of the project are examined: NGO critics, high staff turnover, corruption, labour issues, thefts, lack of local support, as well as problems with contractors, land disputes and the Ebola epidemic.! ! ! "ii ! ! "iii Acknowledgement! ! First and foremost I would like to thank my research team in Sierra Leone, Fabian Käser and Franziska Marfurt for the great collaboration and our supervisors Prof. -

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone Tristan Reed1 James A. Robinson2 July 15, 2013 1Harvard University, Department of Economics, Littauer Center, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. 2Harvard University, Department of Government, IQSS, 1737 Cambridge Street., N309, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract1 In this manuscript, a companion to Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson (2013), we provide a detailed history of Paramount Chieftaincies of Sierra Leone. British colonialism transformed society in the country in 1896 by empowering a set of Paramount Chiefs as the sole authority of local government in the newly created Sierra Leone Protectorate. Only individuals from the designated \ruling families" of a chieftaincy are eligible to become Paramount Chiefs. In 2011, we conducted a survey in of \encyclopedias" (the name given in Sierra Leone to elders who preserve the oral history of the chieftaincy) and the elders in all of the ruling families of all 149 chieftaincies. Contemporary chiefs are current up to May 2011. We used the survey to re- construct the history of the chieftaincy, and each family for as far back as our informants could recall. We then used archives of the Sierra Leone National Archive at Fourah Bay College, as well as Provincial Secretary archives in Kenema, the National Archives in London and available secondary sources to cross-check the results of our survey whenever possible. We are the first to our knowledge to have constructed a comprehensive history of the chieftaincy in Sierra Leone. 1Oral history surveys were conducted by Mohammed C. Bah, Alimamy Bangura, Alieu K. -

A Sub-National Case Study of Liberal Peacebuilding in Sierra Leone and Liberia

Department of Political Science McGill University Harmonizing Customary Justice with the Rule of Law? A Sub-national Case Study of Liberal Peacebuilding in Sierra Leone and Liberia By Mohamed Sesay A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Mohamed Sesay, 2016 ABSTRACT One of the greatest conundrums facing postwar reconstruction in non-Western countries is the resilience of customary justice systems whose procedural and substantive norms are often inconsistent with international standards. Also, there are concerns that subjecting customary systems to formal regulation may undermine vital conflict resolution mechanisms in these war-torn societies. However, this case study of peacebuilding in Sierra Leone and Liberia finds that primary justice systems interact in complex ways that are both mutually reinforcing and undermining, depending on the particular configuration of institutions, norms, and power in the local sub-national context. In any scenario of formal and informal justice interaction (be it conflictual or cooperative), it matters whether the state justice system is able to deliver accessible, affordable, and credible justice to local populations and whether justice norms are in line with people’s conflict resolution needs, priorities, and expectations. Yet, such interaction between justice institutions and norms is mediated by underlying power dynamics relating to local political authority and access to local resources. These findings were drawn from a six-month fieldwork that included collection of documentary evidence, observation of customary courts, and in-depth interviews with a wide range of stakeholders such as judicial officials, paralegals, traditional authorities, as well as local residents who seek justice in multiple forums. -

Ma Franziska Final.Compressed

Ethnography of Land Deals Local Perceptions of a Bioenergy Project in Sierra Leone –Expectations of Modernity, Gendered Impacts and Coping Strategies– Master Thesis of Franziska Marfurt Master of Arts in Social Anthropology Institute of Social Anthropology University of Bern Supervisor [email protected] Prof. Dr. Tobias Haller 07-209-331 Submitted 21.01.2016 To Franziska Conteh and the People of Worreh Yeama Abstract In the last decade with have witnessed a rise in large-scale land acquisition projects on a global scale. Despite increased research activity, data on concrete implementation processes and perceptions of different groups of affected people remain sparse. This thesis aims to address this research gap by providing empirical in-depth knowledge on the investment case of the Swiss-based company Addax Bioenergy in Sierra Leone. The four-month fieldwork addressed questions of consultation, perceptions, impacts on livelihoods and coping strategies. Findings reveal gendered impacts on access to land and resources and adverse effects on livelihood strategies of women who have been marginalised through the formalisation of customary land rights. However, evidence shows that women and other groups of affected people are capable of organizing within a complex institutional setting. Through alliances with various actors they manage to influence the outcomes of the Bioenergy project through acts of resistance and therewith prevent further deterioration of resilience of livelihoods. Key Words: Large scale land acquisition, local impacts, land rights, gender, development, resistance. i Acknowledgments The writing of this thesis would not have been possible without all the people who have supported me during my fieldwork and the process of writing. -

Lustenberger-Addax-Bioenergy-Sierra

Institute of Geography of the University of Bern! Master Thesis! Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Stephan Rist! ! Addax Bioenergy Sierra Leone! ! Analysis of the implementation process of a large scale land acquisition project from the perspective of assemblage theory! ! ! ! Samuel M. Lustenberger ! 09-203-183! [email protected]! 30.03.2014! ! Abstract! ! This thesis presents an analysis of the implementation process of the Addax Bioenergy project in Sierra Leone from the perspective of assemblage theory. It seeks to contribute to an ongoing debate about Large Scale Land acquisition in countries of the Global South. The case study addresses research questions about the preconditions, the concrete implementation and occurring counteracting processes of such a project. The findings are based on a set of qualitative methods applied during a 4 months field stay in Sierra Leone from August until December 2013.! Five important elements are identified that enabled the coming into being of the Addax Bioenergy project: The mother company AOG, the Biofuel Complex, the European Union, Development Finance Institutions and Sierra Leone as the place of operation.! They were linked together by a social network of people with the right skills, connections or positions in a complex process that took place over several years. A range of factors that were working against the formation of the project are examined: NGO critics, high staff turnover, corruption, labour issues, thefts, lack of local support, as well as problems with contractors, land disputes and the Ebola epidemic.! ! ! "ii ! ! "iii Acknowledgement! ! First and foremost I would like to thank my research team in Sierra Leone, Fabian Käser and Franziska Marfurt for the great collaboration and our supervisors Prof. -

![[NEC] – 2017 FINAL LIST of VOTER REGISTRATION CENTRES Region](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3710/nec-2017-final-list-of-voter-registration-centres-region-4843710.webp)

[NEC] – 2017 FINAL LIST of VOTER REGISTRATION CENTRES Region

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSI ON [NEC] – 2017 FINAL LIST OF VOTER REGISTRATION CENTRES Region District Constituency Ward Centre Code CentreName Eastern Kailahun 1 1 1001 Town Barray,Kamakpodu Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1002 Town Barray, Falama Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1003 Town Barray, Dambar Eastern Kailahun 1 1 1004 Sandia Community Barray, Sandia Eastern Kailahun 1 1 1005 Town Barray, Taidu Eastern Kailahun 1 1 1006 Open Space, Killima Town Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1007 NA court Barray, Buedu Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1008 Buedu Community Centre, Buedu Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1009 R.C Primary School, Buedu Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1010 KLDEC, Weh Town Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1011 Open Space, Mendekuama Town Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1012 Town Barray, Koldu Bendu Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1013 Court Barray , Tongi tingi, Dawa Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1014 Town Barray, Tongi tingi, Vuahun Town Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1015 Court Barray, Tongi tingi, Mandopolahun Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1016 Town Barray, Damballu Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1017 Mano Town Barray, M.Tingi Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1018 Town Barray, Benduma Town Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1019 Town Barray, Kamadu Town Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1020 Town Barray, Gbalama Town Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1021 Town Barray, Lela, Fowa Town Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1022 Gbahama Town, Lela Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1023 Court Barray, Kangama Town Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1024 KLDEC School, Kangama Town Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1025 Open Space, Yenlendu Town Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1026 Town Barray, Tangabu Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1027 History Ministry Church Kpekeledu Town Eastern -

Sierra Leone:Bombali District Reference

<all other values> Sierra Leone:Bombali District Reference Map ntlclass primary road secondary tertiary Moria Primary Roads Main Rivers Thalla GUINEA Secondary Roads Dugutha Section Tambakha Tertiary Roads Chiefdom Paramount Chief Se o Mong s Main Rivers e i c r wrl_polbnda_int_15m_uncs a c S t District a Simibue e r G Koinadugu Chiefdom Samia Kayimbor Sella Limba Kamakwie Makwie Loko Section Kamankoh Magbonkoni I Sanda Loko Kindia Madina Kagbankuna Magbonkoni IIManonkoh RothathaBanka Benia KaindemaKamalu Laminaya Bombali Makapa Maparay Maharibo Timbo Sokudala Manathi Yana Karassa SIERRA LEONE Kambia Sendugu A Kawungulu Sendugu B Romaneh Makulon Magbaimba Ndorh Gbenkfay Makendema Biriwa Mambiama R Gbanti Kamarank Sakuma B Kabakeh/Balandugu o Royeama B k Sakuma A e Gbonkobana l Rogberay o Makumray A Royeama A HunduwaManjahagha r Kayourgbor Kayonkoro S Makumray B e Karina l Rogbin Kagberay i Lobanga Kambia MarampaYankabala Sendugu KababalaTanyehun Kukuna Rogboreh Gbendembu Ngowa Bumban Rosos Sanda Tendaran Makai Lohindie Masisan Mateboi Loko-Madina Mayorthan Sahun Bumbandain Kasengbeh Makayrembay Gbendembu Batkanu Kania Kamabai le Mafonda o Matehun Makump Masapi b Mayankay a Mamaka Makarihiteh Kayassi M Magbanamba Libeisaygahun Mamukay Makeregbohun Kalangba Bombali Bana Kabonka Simbaya Mandawahun Tambiama Garanganwa Robaka Makaiba Masongbo Safroko Limba Mabamba Rotha-Tha Gborbana Binkolo ManyakoiMagbaingba Punthun Mabanta Mangay Makeni Town Tonkolili Rosint e Tonkoba Masongbo A b KathanthanKathegeya g Magbenteh a Little B Scarcies Makari Gbanti MankeneKagbaran Dokom B RosandaPaki Masabong Port Loko Masongbo B Kafala Mapaki n e d n Bombali Sebora e Yainkassa S r Kono Konta Mayagba o a Matotoka n a p Masabong m Bafi a P e y e S T e w a The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

2011 Survey of Availability of Modern

2011 Survey of Availability of Modern Contracep•ves and Essen•al Life-Saving Maternal and Reproduc•ve Health Medicines in Service Delivery Points in Sierra Leone: ANALYTICAL REPORT AND TABLES March 2012 UNFPA SIERRA LEONE PREFACE This is the second annual report of the ‘Survey of Modern Contra ceptives and Essential Lifesaving Maternal and Reproductive Health Medicines in Service Delivery Points’ in Sierra Leone. As part of the reporting system of the Global Programme on Reproductive Health Commodity Security (GPRHCS), it generates time series data on reproduct ive health commodity security including the three country level indicators of: (a) Percentage of Service Delivery Points (SDPs) offering at least three modern contraceptive methods; (b) Percentage of SDPs where five selected lifesaving (including th ree essential) lifesaving maternal/reproductive health medicines are available in all facilities providing delivery services, and (c) Percentage of SDPs with ‘no stock-outs’ of modern contraceptives in the last six months prior to the survey (April-September 2011). Government of Sierra Leone and UNFPA appreciate the invaluab le contributions of individuals and institutions towards the success of the 2011 su rvey round in Sierra Leone. We are grateful to the Steering Committee of the surveys on rep roductive health commodity security (RHCS). The co-Chairs of the Reproductive Health Division (RHD) and Parliamentary Committee on Health and Sanitation (MoHS) with th eir membership comprising of stakeholders in the health sector are appreciated f or their oversight functions. We also recognize the technical inputs of the Technical Commit tee that is chaired jointly by the Department of Policy, Planning and Information (DPPI) of Mo HS and Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL). -

Effects of the Addax Bioenergy Investment on Female Farmers’ Rights to Land and Their Livelihoods in Bombali District, Sierra Leone

Lund University Master of Science in International Development and Management Photo: Addax Bioenergy-Sugarcane-Biofuel Project: (Photo by Benjamin John Sesay) EFFECTS OF THE ADDAX BIOENERGY INVESTMENT ON FEMALE FARMERS’ RIGHTS TO LAND AND THEIR LIVELIHOODS IN BOMBALI DISTRICT, SIERRA LEONE Author: Benjamin John Sesay No Supervisor May 2015 1 Abstract Attempts to promote women’s rights to land in Sub-Saharan Africa have attracted attention in both academia and from an international development perspective. Female Farmers (FFs) in Bombali district in northern Sierra Leone gain access to farmland through male heritages under customary practices. This makes them dependent on maintaining connections with male lineages in order to gain rights to land, which include ownership, control, as well as access and use. The Swiss based company, Addax Bioenergy is involved in a sugarcane-biofuel-project in the district of Bombali, which has led to land ownership shifting legally to the company on a long-term lease. Land access and use have been limited in areas, which overlap the company’s project site. Proponents of the Addax Bioenergy project have assumed such investment would contribute to Sierra Leone’s development strides. This thesis examines three key concepts which include: ways of acquiring farmland and the Addax Bioenergy’s Large-Scale Land Acquisition (LSLA), the female farmers’ understanding of LSLA, and the impact on the rights to land and livelihoods. The thesis uses a mixed method approach together with Noam Chomsky’s (1999) theoretical framework on profit over people: neoliberalism and the global order, and Naila Kabeer’s (2005) Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment to analyse the data aimed at answering the research question.