Treatment Options for Atopic Dermatitis LUCINDA M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2008/0317805 A1 Mckay Et Al

US 20080317805A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2008/0317805 A1 McKay et al. (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 25, 2008 (54) LOCALLY ADMINISTRATED LOW DOSES Publication Classification OF CORTICOSTEROIDS (51) Int. Cl. A6II 3/566 (2006.01) (76) Inventors: William F. McKay, Memphis, TN A6II 3/56 (2006.01) (US); John Myers Zanella, A6IR 9/00 (2006.01) Cordova, TN (US); Christopher M. A6IP 25/04 (2006.01) Hobot, Tonka Bay, MN (US) (52) U.S. Cl. .......... 424/422:514/169; 514/179; 514/180 (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: This invention provides for using a locally delivered low dose Medtronic Spinal and Biologics of a corticosteroid to treat pain caused by any inflammatory Attn: Noreen Johnson - IP Legal Department disease including sciatica, herniated disc, Stenosis, mylopa 2600 Sofamor Danek Drive thy, low back pain, facet pain, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid Memphis, TN38132 (US) arthritis, osteolysis, tendonitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, or tarsal tunnel syndrome. More specifically, a locally delivered low dose of a corticosteroid can be released into the epidural (21) Appl. No.: 11/765,040 space, perineural space, or the foramenal space at or near the site of a patient's pain by a drug pump or a biodegradable drug (22) Filed: Jun. 19, 2007 depot. E Day 7 8 Day 14 El Day 21 3OO 2OO OO OO Control Dexamethasone DexamethasOne Dexamethasone Fuocinolone Fluocinolone Fuocinolone 2.0 ng/hr 1Ong/hr 50 ng/hr 0.0032ng/hr 0.016 ng/hr 0.08 ng/hr Patent Application Publication Dec. 25, 2008 Sheet 1 of 2 US 2008/0317805 A1 900 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 80.0 - 7OO – 6OO - 5OO - E Day 7 EDay 14 40.0 - : El Day 21 2OO - OO = OO – Dexamethasone Dexamethasone Dexamethasone Fuocinolone Fluocinolone Fuocinolone 2.0 ng/hr 1Ong/hr 50 ng/hr O.OO32ng/hr O.016 ng/hr 0.08 nghr Patent Application Publication Dec. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 De Juan Et Al

US 200601 10428A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 de Juan et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) METHODS AND DEVICES FOR THE Publication Classification TREATMENT OF OCULAR CONDITIONS (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Eugene de Juan, LaCanada, CA (US); A6F 2/00 (2006.01) Signe E. Varner, Los Angeles, CA (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/427 (US); Laurie R. Lawin, New Brighton, MN (US) (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: Featured is a method for instilling one or more bioactive SCOTT PRIBNOW agents into ocular tissue within an eye of a patient for the Kagan Binder, PLLC treatment of an ocular condition, the method comprising Suite 200 concurrently using at least two of the following bioactive 221 Main Street North agent delivery methods (A)-(C): Stillwater, MN 55082 (US) (A) implanting a Sustained release delivery device com (21) Appl. No.: 11/175,850 prising one or more bioactive agents in a posterior region of the eye so that it delivers the one or more (22) Filed: Jul. 5, 2005 bioactive agents into the vitreous humor of the eye; (B) instilling (e.g., injecting or implanting) one or more Related U.S. Application Data bioactive agents Subretinally; and (60) Provisional application No. 60/585,236, filed on Jul. (C) instilling (e.g., injecting or delivering by ocular ion 2, 2004. Provisional application No. 60/669,701, filed tophoresis) one or more bioactive agents into the Vit on Apr. 8, 2005. reous humor of the eye. Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 1 of 22 US 2006/0110428A1 R 2 2 C.6 Fig. -

Pruritus: Scratching the Surface

Pruritus: Scratching the surface Iris Ale, MD Director Allergy Unit, University Hospital Professor of Dermatology Republic University, Uruguay Member of the ICDRG ITCH • defined as an “unpleasant sensation of the skin leading to the desire to scratch” -- Samuel Hafenreffer (1660) • The definition offered by the German physician Samuel Hafenreffer in 1660 has yet to be improved upon. • However, it turns out that itch is, indeed, inseparable from the desire to scratch. Savin JA. How should we define itching? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2 Pt 1):268-9. Pruritus • “Scratching is one of nature’s sweetest gratifications, and the one nearest to hand….” -- Michel de Montaigne (1553) “…..But repentance follows too annoyingly close at its heels.” The Essays of Montaigne Itch has been ranked, by scientific and artistic observers alike, among the most distressing physical sensations one can experience: In Dante’s Inferno, falsifiers were punished by “the burning rage / of fierce itching that nothing could relieve” Pruritus and body defence • Pruritus fulfils an essential part of the innate defence mechanism of the body. • Next to pain, itch may serve as an alarm system to remove possibly damaging or harming substances from the skin. • Itch, and the accompanying scratch reflex, evolved in order to protect us from such dangers as malaria, yellow fever, and dengue, transmitted by mosquitoes, typhus-bearing lice, plague-bearing fleas • However, chronic itch lost this function. Chronic Pruritus • Chronic pruritus is a common and distressing symptom, that is associated with a variety of skin conditions and systemic diseases • It usually has a dramatic impact on the quality of life of the affected individuals Chronic Pruritus • Despite being the major symptom associated with skin disease, our understanding of the pathogenesis of most types of itch is limited, and current therapies are often inadequate. -

Effect of Intra-Articular Triamcinolone Vs Saline on Knee

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 -

(Phacs) in the Snow Deposition Near Jiaozhou Bay, North China

applied sciences Article Characterization, Source and Risk of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PhACs) in the Snow Deposition Near Jiaozhou Bay, North China Quancai Peng 1,2,3,4, Jinming Song 1,2,3,4,*, Xuegang Li 1,2,3,4, Huamao Yuan 1,2,3,4 and Guang Yang 1,2,3,4 1 CAS Key Laboratory of Marine Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China; [email protected] (Q.P.); [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (H.Y.); [email protected] (G.Y.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 Laboratory for Marine Ecology and Environmental Science, Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao), Qingdao 266237, China 4 Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel: +86-0532-8289-8583 Received: 20 February 2019; Accepted: 8 March 2019; Published: 14 March 2019 Abstract: The occurrence and distribution of 110 pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) were investigated in snow near Jiaozhou Bay (JZB), North China. All target substances were analyzed using solid phase extraction followed by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry.A total of 38 compounds were detected for the first time in snow, including 23 antibiotics, eight hormones, three nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, two antipsychotics, one beta-adrenergic receptor and one hypoglycemic drug. The total concentration of PhACs in snow ranged from 52.80 ng/L to 1616.02 ng/L. The compounds found at the highest mean concentrations included tetracycline (125.81 ng/L), desacetylcefotaxime (17.73 ng/L), ronidazole (8.79 ng/L) and triamcinolone diacetate (2.84 ng/L). -

Prior Authorization Required

Prior Authorization Code Short Description Brand Name (for reference) Required 90378 Rsv Mab Im 50mg SYNAGIS Yes C9014 Injection, cerliponase alfa, 1 mg BRINEURA Yes Injection, c‐1 esterase inhibitor (human), haegarda, C9015 HAEGARDA Yes 10 units C9016 Injection, triptorelin extended release, 3.75 mg TRELSTAR DEPOT Yes C9021 Injection, obinutuzumab, 10 mg GAZYVA Yes C9022 Injection, elosulfase alfa, 1mg VIMIZIM Yes C9023 Injection, testosterone undecanoate, 1 mg AVEED Yes Injection, liposomal, 1 mg daunorubicin and 2.27 C9024 VYXEOS Yes mg cytarabine C9025 Injection, ramucirumab, 5 mg CYRAMZA Yes C9026 Injection, vedolizumab, 1 mg ENTYVIO Yes C9027 Injection, pembrolizumab, 1 mg KEYTRUDA Yes C9028 Injection, inotuzumab ozogamicin, 0.1 mg BESPONSA Yes C9029 Injection, guselkumab, 1 mg TREMFYA Yes C9030 Injection, copanlisib, 1 mg ALIQOPA Yes C9031 Lutetium lu 177, dotatate, therapeutic, 1 mci LUTATHERA No Injection, voretigene neparvovec‐rzyl, 1 billion C9032 LUXTURNA Yes vector genome Injection, fosnetupitant 235 mg and palonosetron C9033 AKYNZEO Yes 0.25 mg C9034 Injection, dexamethasone 9%, intraocular, 1 mcg DEXYCU Yes Injection, aripiprazole Injection, aripiprazole lauroxil (aristada initio), 1 C9035 lauroxil (aristada initio), 1 Yes mg mg C9036 Injection, patisiran, 0.1 mg ONPATTRO Yes C9037 Injection, risperidone (perseris), 0.5 mg PERSERIS Yes C9038 Injection, mogamulizumab‐kpkc, 1 mg POTELIGEO Yes C9039 Injection, plazomicin, 5 mg ZEMDRI Yes Injection, fremanezumab‐ C9040 Injection, fremanezumab‐vfrm, 1 mg Yes vfrm, 1 mg Injection, -

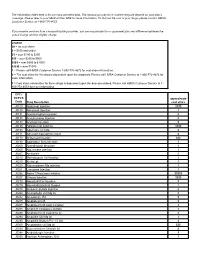

CPT / HCPCS Code Drug Description Approximate Cost Share

The information listed here is for our most prevalent plan. The amount you pay for a covered drug will depend on your plan’s coverage. Please refer to your Medical Plan GTB for more information. To find out the cost of your drugs, please contact HMSA Customer Service at 1-800-776-4672. If you receive services from a nonparticipating provider, you are responsible for a copayment plus any difference between the actual charge and the eligible charge. Legend $0 = no cost share $ = $100 and under $$ = over $100 to $250 $$$ = over $250 to $500 $$$$ = over $500 to $1000 $$$$$ = over $1000 1 = Please call HMSA Customer Service 1-800-776-4672 for cost share information. 2 = The cost share for this drug is dependent upon the diagnosis. Please call HMSA Customer Service at 1-800-772-4672 for more information. 3 = Cost share information for these drugs is dependent upon the dose prescribed. Please call HMSA Customer Service at 1- 800-772-4672 for more information. CPT / HCPCS approximate Code Drug Description cost share J0129 Abatacept Injection $$$$ J0130 Abciximab Injection 3 J0131 Acetaminophen Injection $ J0132 Acetylcysteine Injection $ J0133 Acyclovir Injection $ J0135 Adalimumab Injection $$$$ J0153 Adenosine Inj 1Mg $ J0171 Adrenalin Epinephrine Inject $ J0178 Aflibercept Injection $$$ J0180 Agalsidase Beta Injection 3 J0200 Alatrofloxacin Mesylate 3 J0205 Alglucerase Injection 3 J0207 Amifostine 3 J0210 Methyldopate Hcl Injection 3 J0215 Alefacept 3 J0220 Alglucosidase Alfa Injection 3 J0221 Lumizyme Injection 3 J0256 Alpha 1 Proteinase Inhibitor -

Joint Injection Workshop

Joint Injection Workshop Dr Laurel Young Redcliffe and Northside Rheumatology (RNR) Joint injections • Indications • Type of steroid and why • Technique • Complications • Consent – verbal, written • Imaging? Indications for aspirating or injecting joints/soft tissues Reasons for joint aspirations Reasons for injections Exclude infection (mandatory) Diagnostic – eg. LA Therapeutic Diagnostic e.g crystals, (relieve symptoms) inflammation Joints, tendon sheaths, bursa, CTS What to inject? Type of steroid Duration in joint - solubility Corticosteroid Solubility Cost Betamethasone sodium phosphate Most soluble Dexamethasone sodium phosphate Soluble Prednisone sodium phosphate Soluble Methylprednisolone acetate Slightly soluble $4.72 (40mg/vial) Betamethasone sodium phosphate + Slightly soluble $5.34 Bethamethasone acetate (2.96/2.71mg/vial) Triamcinolone diacetate Slightly soluble Prednisolone tebutate Slightly soluble Trimancinolone acetonide Relatively insoluble $27.25 (10mg/vial) $81.39 (40mg/vial) Triamcinolone hexacetonide Relatively insoluble Hydrocortisone acetate Relatively insoluble Dexamethasone acetate Relatively insoluble Fluorinated vs non-fluorinated steroids Methylprednisolone acetate Triamcinolone acetonide Betamethasone Fluorinated steroids risk in s/c injections – fat necrosis, hypopigmentation Corticosteroid Fluorinated Betamethasone sodium phosphate Yes Betamethasone sodium Yes phosphoate/Betamethasone acetate Dexamethasone sodium phosphate Yes Triamcinolone diacetate Yes Trimancinolone acetonide Yes Triamcinolone hexacetonide -

Wo 2008/127291 A2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (43) International Publication Date PCT (10) International Publication Number 23 October 2008 (23.10.2008) WO 2008/127291 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: Jeffrey, J. [US/US]; 106 Glenview Drive, Los Alamos, GOlN 33/53 (2006.01) GOlN 33/68 (2006.01) NM 87544 (US). HARRIS, Michael, N. [US/US]; 295 GOlN 21/76 (2006.01) GOlN 23/223 (2006.01) Kilby Avenue, Los Alamos, NM 87544 (US). BURRELL, Anthony, K. [NZ/US]; 2431 Canyon Glen, Los Alamos, (21) International Application Number: NM 87544 (US). PCT/US2007/021888 (74) Agents: COTTRELL, Bruce, H. et al.; Los Alamos (22) International Filing Date: 10 October 2007 (10.10.2007) National Laboratory, LGTP, MS A187, Los Alamos, NM 87545 (US). (25) Filing Language: English (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AT,AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY,BZ, CA, CH, (30) Priority Data: CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, 60/850,594 10 October 2006 (10.10.2006) US ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, (71) Applicants (for all designated States except US): LOS LR, LS, LT, LU, LY,MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, ALAMOS NATIONAL SECURITY,LLC [US/US]; Los MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PG, PH, PL, Alamos National Laboratory, Lc/ip, Ms A187, Los Alamos, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, SV, SY, NM 87545 (US). -

Injectable Medication Hcpcs/Dofr Crosswalk

INJECTABLE MEDICATION HCPCS/DOFR CROSSWALK HCPCS DRUG NAME GENERIC NAME PRIMARY CATEGORY SECONDARY CATEGORY J0287 ABELCET Amphotericin B lipid complex THERAPEUTIC INJ HOME HEALTH/INFUSION** J0400 ABILIFY Aripiprazole, intramuscular, 0.25 mg THERAPEUTIC INJ J0401 ABILIFY MAINTENA Apriprazole 300mg, IM injection THERAPEUTIC INJ J9264 ABRAXANE paclitaxel protein-bound particles, 1 mg J1120 ACETAZOLAMIDE SODIUM Acetazolamide sodium injection THERAPEUTIC INJ J0132 ACETYLCYSTEINE INJ Acetylcysteine injection, 10 mg THERAPEUTIC INJ ACTEMRA INJECTION (50242-0136-01, J3262 50242-0137-01) Tocilizumab 200mg, 400mg THERAPEUTIC INJ ACTEMRA 162mg/0.9ml Syringe (50242- J3262 SELF-INJECTABLE 0138-01) Tocilizumab, 1 mg J0800 ACTHAR HP Corticotropin injection THERAPEUTIC INJ Hemophilus influenza b vaccine (Hib), PRP-T conjugate (4- 90648 ACTHIB dose schedule), for intramuscular use THERAPEUTIC INJ IMMUNIZATIONS J0795 ACTHREL Corticorelin ovine triflutal THERAPEUTIC INJ J9216 ACTIMMUNE Interferon gamma 1-b 3 miillion units SELF-INJECTABLE CHEMO ADJUNCT* J2997 ACTIVASE Alteplase recombinant, 1mg THERAPEUTIC INJ HOME HEALTH/INFUSION** J0133 ACYCLOVIR SODIUM Acyclovir, 5 mg THERAPEUTIC INJ HOME HEALTH/INFUSION** 90715 ADACEL Tdap vaccine, > 7 yrs, IM THERAPEUTIC INJ IMMUNIZATIONS J2504 ADAGEN Pegademase bovine, 25 IU THERAPEUTIC INJ HOME HEALTH/INFUSION** J9042 ADCETRIS Brentuximab vedotin Injection THERAPEUTIC INJ CHEMOTHERAPY J0153 ADENOCARD Adenosine 6 MG THERAPEUTIC INJ J0171 ADRENALIN Adrenalin (epinephrine) inject THERAPEUTIC INJ J9000 ADRIAMYCIN Doxorubicin -

Using F-NMR and H-NMR for Analysis of Glucocorticosteroids in Creams

KTH Royal Institute of Technology School of Chemical Engineering Degree project, in KD203X, second level, 2010 Using 19F-NMR and 1H-NMR for Analysis of Glucocorticosteroids in Creams and Ointments - Method Development for Screening, Quantification and Discrimination Angelica Lehnström Supervisors Monica Johansson, Medical Products Agency Ian McEwen, Medical Products Agency Examiner István Furó, Royal Institute of Technology Abstract Topical treatment containing undeclared corticosteroids and illegal topical treatment with corticosteroid content have been seen on the Swedish market. In creams and ointments corticosteroids in the category of glucocorticosteroids are used to reduce inflammatory reactions and itchiness in the skin. If the inflammation is due to bacterial infection or fungus, complementary treatment is necessary. Side effects of corticosteroids are skin reactions and if used in excess suppression of the adrenal gland function. Therefore the Swedish Medical Products Agency has published related warnings to make the public aware. There are many similar structures of corticosteroids where the anti-inflammatory effect is depending on substitutions on the corticosteroid molecular skeleton. In legal creams and ointments they can be found at concentrations of 0.025 - 1.0 %, where corticosteroids with fluorine substitutions usually are found at concentrations up to 0.1 % due to increased potency. At the Medical Products Agency 19F-NMR and 1H-NMR have been used to detect and quantify corticosteroid content in creams and ointments. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, NMR, is an analytical technique which is quite sensitive and can have a relative short experimental time. The low concentration of corticosteroids makes the signals detected in NMR small and in 1H-NMR the signals are often overlapped by signals from the matrix. -

Musculoskeletal Corticosteroid Use: Types, Indications, Contraindications, Equivalent Doses, Frequency of Use and Adverse Effects

Musculoskeletal corticosteroid use: Types, Indications, Contraindications, Equivalent doses, Frequency of use and Adverse effects. Dr Jide Olubaniyi MBBS, FRCR Dr Sean Crowther MB BCh, MRCS, FRCR Dr Sukhvinder Dhillon, MB ChB, FRCR Corticosteroid Use • Reduce inflammation, alleviate pain and restore function. • Management of degenerative diseases, inflammatory diseases and post-traumatic soft tissue injury. • Administered safely into joint space, peri- articular soft tissues, bursa and tendon sheaths. Disclosure • Dr Jide Olubaniyi – No disclosure • Dr Sean Crowther – No disclosure • Dr Sukhvinder Dhillon – Speaker, Ankylosis Spondylitis workshop, AbbVie. Mechanism of Action Binds onto intracellular glucocorticoid receptor Receptor-ligand complex translocates into cell nucleus and binds onto target genes Upregulation of Annexin-1 Inhibition of prostaglandin and leukotrienes production Reduction of synovial blood flow and leucocyte accumulation Reduction of inflammation and pain Classification • Soluble • Insoluble • Dissolve freely in water • Require hydrolysis by • Non-particulate (clear) cellular esterases • Non-esters • Particulate • Quick onset of action • Contain esters • Shorter duration of action • Longer onset of action • Longer duration of action • Dexamethasone • Triamcinolone • Betamethasone • Methylprednisolone Methylprednisolone acetate (Depo- medrol) FDA-approved types Methylprednisolone sodium succinate (Solu- Medrol) Triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) Triamcinolone hexacetonide (Aristospan) Triamcinolone diacetate (Aristocort