GHA Lifestyle Report2015lr.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

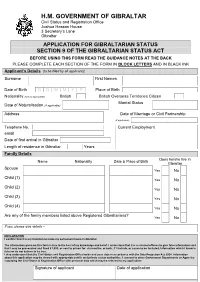

Application for Gibraltarian Status (Section 9)

H.M. GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR Civil Status and Registration Office Joshua Hassan House 3 Secretary’s Lane Gibraltar APPLICATION FOR GIBRALTARIAN STATUS SECTION 9 OF THE GIBRALTARIAN STATUS ACT BEFORE USING THIS FORM READ THE GUIDANCE NOTES AT THE BACK PLEASE COMPLETE EACH SECTION OF THE FORM IN BLOCK LETTERS AND IN BLACK INK Applicant’s Details (to be filled by all applicants) Surname First Names Date of Birth D D M M Y Y Place of Birth Nationality (tick as appropriate) British British Overseas Territories Citizen Marital Status Date of Naturalisation (if applicable) Address Date of Marriage or Civil Partnership (if applicable) Telephone No. Current Employment email Date of first arrival in Gibraltar Length of residence in Gibraltar Years Family Details Does he/she live in Name Nationality Date & Place of Birth Gibraltar Spouse Yes No Child (1) Yes No Child (2) Yes No Child (3) Yes No Child (4) Yes No Are any of the family members listed above Registered Gibraltarians? Yes No If yes, please give details – DECLARATION I confirm that it is my intention to make my permanent home in Gibraltar. The information given on this form is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. I understand that it is a criminal offence to give false information and that I may be prosecuted and fined £1,000, or sent to prison for six months, or both, if I include, or cause to be included, information which I know is false or do not believe to be true. I also understand that the Civil Status and Registration Office holds and uses data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2004. -

Excursion from Puerto Banús to Gibraltar by Jet

EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR BY JET SKI EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR Marbella Jet Center is pleased to present you an exciting excursion to discover Gibraltar. We propose a guided historical tour on a jet ski, along the historic and picturesque coast of Gibraltar, aimed at any jet ski lover interested in visiting Gibraltar. ENVIRONMENT Those who love jet skis who want to get away from the traffic or prefer an educational and stimulating experience can now enjoy a guided tour of the Gibraltar Coast, as is common in many Caribbean destinations. Historic, unspoiled and unadorned, what better way to see Gibraltar's mighty coastline than on a jet ski. YOUR EXPERIENCE When you arrive in Gibraltar, you will be taken to a meeting point in “Marina Bay” and after that you will be accompanied to the area where a briefing will take place in which you will be explained the safety rules to follow. GIBRALTAR Start & Finish at Marina Bay Snorkelling Rosia Bay Governor’s Beach & Gorham’s Cave Light House & Southern Defenses GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI After the safety brief: Later peoples, notably the Moors and the Spanish, also established settlements on Bay of Gibraltar the shoreline during the Middle Ages and early modern period, including the Heading out to the center of the bay, tourists may have a chance to heavily fortified and highly strategic port at Gibraltar, which fell to England in spot the local pods of dolphins; they can also have a group photograph 1704. -

An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar

.............................................................................................................................................................................................................WORK IN PROGESS WORK IN PROGRESS TOMASZ PACIORKOWSKI DOI: 10.15290/CR.2018.23.4.05 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar Abstract. Gibraltar, popularly known as “The Rock”, has been a British overseas territory since the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713. The demographics of this unique colony reflect its turbulent past, with most of the population being of Spanish, Portuguese or Italian origin (Garcia 1994). Additionally, there are prominent minorities of Indians, Maltese, Moroccans and Jews, who have also continued to influence both the culture and the languages spoken in Gibraltar (Kellermann 2001). Despite its status as the only English overseas territory in continental Europe, Gibraltar has so far remained relatively neglected by scholars of sociolinguistics, new dialect formation, and World Englishes. The paper provides a summary of the current state of sociolinguistic research in Gibraltar, focusing on such aspects as identity formation, code-switching, language awareness, language attitudes, and norms. It also delineates a plan for further research on code-switching and national identity following the 2016 Brexit referendum. Keywords: Gibraltar, code-switching, sociolinguistics, New Englishes, dialect formation, Brexit. 1. Introduction Gibraltar is located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula and measures just about 6 square kilometres. This small size, however, belies an extraordinarily complex political history and social fabric. In the Brexit referendum of 23rd of June 2016, the inhabitants of Gibraltar overwhelmingly expressed their willingness to continue belonging to the European Union, yet at the moment it appears that they will be forced to follow the decision of the British govern- ment and leave the EU (Garcia 2016). -

How Gibraltar Got Its Name Bond Was Here

Travel Bond was here From the Rock, we also had great views of many yachts moored in the marinas. Gibraltar Harbour may look familiar to 007 aficionados. In You Only Live Twice, Sean Connery was supposedly buried at sea in Hong Kong Harbour, but the ruse burial was actually filmed from the HMS Tenby in Gibraltar Harbour. The Upper Rock was the 1987 film location for The Living Daylights. The opening NATO exercise scene starred Timothy Dalton, with some mischievous macaques as extras. Sean Connery liked Gibraltar so much that he married his first and second wives here. Gibraltar Harbour where Sean Connery starred in You Only Live Twice Another James Bond, Roger Moore and his new wife honeymooned in Gibraltar. Sean Connery and Diane Cilento stayed Until we travelled here, we didn’t know that at The Rock Hotel after their wedding. Gibraltar is an excellent place for viewing In 1969, John Lennon and Yoko Ono signed Completely different is the Sunborn Gibraltar, dolphins year-round. Our Dolphin Adventure their marriage papers at the Registry Office. a floating hotel inside a 142-metre yacht. It’s ticket pictured the most common species that Charles and Diana boarded the royal yacht located in Ocean Village Marina, from where frolic in the Bay of Gibraltar – bottlenose, Britannia in Gibraltar for their 11-day dolphin-watching cruises depart. common and striped. Mediterranean cruise honeymoon. Pedestrians walk through one of the arched gates by the Southport Wall How Gibraltar got its name Much of the town centre is protected by the the rock above the town. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE No: 756/2015 Date: 21st October 2015 Gibraltar authors bring Calpean zest to Literary Festival events As the date for the Gibunco Gibraltar Literary Festival draws closer, the organisers have released more details of the local authors participating in the present edition. The confirmed names are Adolfo Canepa, Richard Garcia, Mary Chiappe & Sam Benady and Humbert Hernandez. Former AACR Chief Minister Adolfo Canepa was Sir Joshua Hassan’s right-hand man for many years. Currently Speaker and Mayor of the Gibraltar Parliament, Mr Canepa recently published his memoirs ‘Serving My Gibraltar,’ where he gives a candid account of his illustrious and extensive political career. Interestingly, Mr Canepa, who was first elected to the Rock’s House of Assembly in 1972, has held all the major public offices in Gibraltar, including that of Leader of the Opposition. Richard Garcia, a retired teacher, senior Civil Servant and former Chief Secretary, is no stranger to the Gibunco Gibraltar Literary Festival. He has written numerous books in recent years delving into the Rock's social history including the evolution of local commerce. An internationally recognised philatelist, Mr Garcia will be presenting his latest work commemorating the 50th anniversary of the event’s main sponsor, the Gibunco Group, and the Bassadone family history since 1737. Mary Chiappe, half of the successful writing tandem behind the locally flavoured detective series ‘The Bresciano Mysteries’ – the other half being Sam Benady – returns to the festival with her literary associate to delight audiences with the suggestively titled ‘The Dead Can’t Paint’, seventh and final instalment of their detective series. -

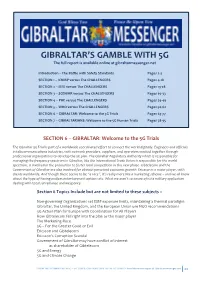

Gibraltar-Messenger.Net

GIBRALTAR’S GAMBLE WITH 5G The full report is available online at gibraltarmessenger.net Introduction – The Battle with Safety Standards Pages 2-3 SECTION 1 – ICNIRP versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 4-18 SECTION 2 – IEEE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 19-28 SECTION 3 – SCENIHR versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 29-33 SECTION 4 – PHE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 34-49 SECTION 5 – WHO versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 50-62 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials Pages 63-77 SECTION 7 – GIBRALTARIANS: Welcome to the 5G Human Trials Pages 78-95 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials The Gibraltar 5G Trial is part of a worldwide coordinated effort to connect the world digitally. Engineers and officials in telecommunications industries, with network providers, suppliers, and operators worked together through professional organizations to develop the 5G plan. The Gibraltar Regulatory Authority which is responsible for managing the frequency spectrum in Gibraltar, like the International Trade Union is responsible for the world spectrum, is involved in the promotion to foster local competition in this new phase. Gibtelecom and the Government of Gibraltar are also involved for obvious perceived economic growth. Ericsson is a major player, with clients worldwide. And though there seems to be “a race”, it’s really more like a marketing scheme – and we all know about the hype of having endless entertainment options etc. What we aren’t so aware of is its military application dealing with total surveillance and weaponry. Section 6 Topics Include but -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE No: 621/2021 Date: 2nd September 2021 Cultural Awards – Public Voting Gibraltar Cultural Services, on behalf of the Ministry of Culture, is pleased to announce that the public voting for the 2021 Cultural Awards will start on Friday 3rd September 2021 and run until the 30th of the month. The telephone numbers have been set up by Gibtelecom and will be available for calls made from Gibtelecom landline and mobiles, with all the monies raised donated to the GBC Open Day fund. The public is encouraged to vote for their preferred nominees, these votes will then be considered by the Cultural Awards Board. The telephone numbers for public voting are as follows: JUNIOR (Under 15’s) 1. Gino Ochello - 8640 ‘Best Youth Actor’ Drama Festival, involved in GAMPA online programming and other Academy performances. 2. Louis Pitto - 8641 Short Story Competition winner (Spring Festival), Poetry Competition Highly Commended (Autumn Festival). 3. Mia Hook- 8642 Overall winner of Bookmark Competition & school years 7/10. 1st Place Jazz Duet & 2nd Place Commercial Solo at online Global Dance Open. YOUTH (Under 25’s) 1. Carmen Anderson - 8643 Ministry of the Environment, Sustainability, Climate Change, Heritage, Education and Culture HM Government of Gibraltar • 1b Leanse Place, 50 Town Range • Gibraltar GX11 1AA t +350 20066491 f +350 20066706 e [email protected] w www.gibraltar.gov.gi ‘Best Supporting Actress’ at Drama Festival, & jointly directed additional play. Online blog, ‘Into the Industry’, series of interviews with professionals working in the Arts. Regular contributor to local papers & magazines. 2. Darius Oliva - 8644 Young Musician of the Year Gibraltar Festival of Young Musicians, Parasol Foundation Scholarship recipient, involved in GAMPA online programming. -

Infogibraltar Servicio De Información De Gibraltar

InfoGibraltar Servicio de Información de Gibraltar Comunicado Gobierno de Gibraltar: Ayuntamiento de Gibraltar Miércoles 11 de noviembre de 2015: 97º aniversario del Armisticio Gibraltar, 7 de octubre de 2015 La undécima hora del undécimo día del undécimo mes se conmemora la firma del Armisticio que marcó el fin de la Primera Guerra Mundial, “la guerra para acabar con la guerra”, el 11 de noviembre de 1918. Como en años previos, la ocasión se conmemorará con una breve ceremonia en el vestíbulo del Parlamento. En este lugar se encuentran inscritos los nombres de los gibraltareños que perdieron la vida en las guerras. Los dos minutos de silencio se indicarán con una salva efectuada por el Real Regimiento de Gibraltar a las 11:00 h. Posteriormente, las cornetas interpretarán The Last Post y se depositarán las coronas de flores. La Teniente de Alcalde Kaiane Aldorino liderará la ceremonia. La Guardia de Honor estará compuesta por el Real Regimiento de Gibraltar y la división gibraltareña de la Royal British Legion1. Las asociaciones y organizaciones interesadas en depositar una corona durante la ceremonia deberán ponerse en contacto con el secretario del alcalde por teléfono: (00350) 200 78956; o correo electrónico: [email protected]. 1 Organización caritativa británica para los veteranos de guerra 07/10/2015 1/3 InfoGibraltar Servicio de Información de Gibraltar Comunicado Nota a redactores: Esta es una traducción realizada por la Oficina de Información de Gibraltar. Algunas palabras no se encuentran en el documento original y se han añadido para mejorar el sentido de la traducción. El texto válido es el original en inglés. -

Wednesday 17Th March 2021

P R O C E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T AFTERNOON SESSION: 3.40 p.m. – 7.40 p.m. Gibraltar, Wednesday, 17th March 2021 Contents Questions for Oral Answer ..................................................................................................... 3 Employment, Health and Safety and Social Security........................................................................ 3 Q519/2020 Health and safety inspections at GibDock – Numbers in 2019 and 2020 ............. 3 Q520/2020 Maternity grants and allowances – Reason for delays in applications ................. 3 Q521/2020 Carers’ allowance – How to apply ......................................................................... 5 Environment, Sustainability, Climate Change and Education .......................................................... 6 Q547/2021 Dog fouling – Number of fines imposed ................................................................ 6 Q548-50/2020 Barbary macaques – Warning signs and safety measures ............................... 7 Q551/2020 Governor’s Street – Tree planting ......................................................................... 8 Q552/2020 School buses – Rationale for cancelling ................................................................ 9 Q553/2020 Fly tipping – Number of complaints and prosecutions ......................................... 9 Q554/2020 Waste Treatment Plan – Update ......................................................................... 11 Q555/2020 Water production – Less energy-intensive -

James Gaggero, Still Flying High Not Many Other Jurisdictions Can Boast Such a Construction Display of Confidence

p6 New Local Bank p26 Pensions Feb/March/April 2010 GIBRALTAR INTERNATIONAL FINANCE AND BUSINESS The Bland Group celebrates its 200th anniversary www.gibraltarinternational.com SPONSORS Gibraltar International Magazine is grateful for the support of the finance industry and allied services (with the encouragement of the Finance Council) in the form of committed sponsorship. We would like to thank the following sponsors: GIBRALTAR FINANCE CENTRE Tel: +(350) 200 50011 Fax: +(350) 200 51818 http://www.gibraltar.gov.gi DELOITTE QUEST INSURANCE MANAGEMENT LTD. Tel: +(350) 200 41200 • Fax + (350) 200 41201 Tel: +(350) 200 74570 • Fax + (350) 200 40901 www.deloitte.gi www.quest.gi EUROPA TRUST COMPANY JYSKE BANK (PRIVATE BANKING) Tel: +(350) 200 79013 • Fax + (350) 200 70101 Tel: +(350) 200 59282 • Fax + (350) 200 76782 www.europa.gi www.jyskebank.gi INVESTGIBRALTAR OFFICE SAPPHIRE NETWORKS Tel: +(350) 200 52634 • Fax + (350) 200 52635 Tel: +(350) 200 47200 • Fax + (350) 200 47272 www.investgibraltar.gov.gi www.sapphire.gi MONARCH AIRLINES PYRILLIUM SOFTWARE Tel: +44 (0) 8700 405040 Tel: + 44 (0)207 3213746 Tel: +(350) 200 47477 Tel: + (350) 200 61449 www.monarch.co.uk www.flymonarch.com www.pyrillium.com HASSANS TRIAY & TRIAY / TOTUS Tel: +(350) 200 79000 • Fax + (350) 200 71966 Tel: + (350) 200 72020 www.gibraltarlaw.com Tel: + (350) 200 76108 www.triay.com • www.totus.com PIRANHA DESIGNS Tel: +(350) 200 45599 • Fax + (350) 200 52037 www.pdg.gi www.gibraltarinternational.com GIBRALTAR INTERNATIONAL 3 February/March/April 2010 EDITORIAL COMMENT Volume 16 / Number 1 Confidence and opportunity in 2010 Contents f we forever look NEWS P6-10 back, we will never New local bank planned see the way ahead”, Banking expands as I tell everyone Five go before when they declare New projects to create jobs “I2009 a terrible year! GDP growth success For in 2010, Gibraltar is Network of Bay ferry services looking forward to the end of high corporation tax, this being the last TELECOMMUNICATIONS P12 year of paying 22 per cent. -

Multiculturalism in the Creation of a Gibraltarian Identity

canessa 6 13/07/2018 15:33 Page 102 Chapter Four ‘An Example to the World!’: Multiculturalism in the Creation of a Gibraltarian Identity Luis Martínez, Andrew Canessa and Giacomo Orsini Ethnicity is an essential concept to explain how national identities are articulated in the modern world. Although all countries are ethnically diverse, nation-formation often tends to structure around discourses of a core ethnic group and a hegemonic language.1 Nationalists invent a dominant – and usually essentialised – narrative of the nation, which often set aside the languages, ethnicities, and religious beliefs of minori- ties inhabiting the nation-state’s territory.2 In the last two centuries, many nation-building processes have excluded, removed or segregated ethnic groups from the national narrative and access to rights – even when they constituted the majority of the population as in Bolivia.3 On other occasions, the hosting state assimilated immigrants and ethnic minorities, as they adopted the core-group culture and way of life. This was the case of many immigrant groups in the USA, where, in the 1910s and 1920s, assimilation policies were implemented to acculturate minorities, ‘in attempting to win the immigrant to American ways’.4 In the 1960s, however, the model of a nation-state as being based on a single ethnic group gave way to a model that recognised cultural diver- sity within a national territory. The civil rights movements changed the politics of nation-formation, and many governments developed strate- gies to accommodate those secondary cultures in the nation-state. Multiculturalism is what many poly-ethnic communities – such as, for instance, Canada and Australia – used to redefine their national identi- ties through the recognition of internal cultural difference. -

Pinkerton A, Benwell MC. Heritage, Strategic Narratives, and the Making of Geopolitical Pasts, Presents and Futures at Europa Point, Gibraltar

Pinkerton A, Benwell MC. Heritage, strategic narratives, and the making of geopolitical pasts, presents and futures at Europa Point, Gibraltar. Political Geography (2018) DOI link https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.12.006 ePrints link http://eprint.ncl.ac.uk/245736 Date deposited 20/02/2018 Embargo release date 13/02/2020 Copyright © 2018. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license Licence This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence Newcastle University ePrints | eprint.ncl.ac.uk Heritage, strategic narratives, and the making of geopolitical pasts, presents and futures at Europa Point, Gibraltar. Alasdair Pinkerton (Royal Holloway, University of London) Matthew C. Benwell (Newcastle University) In June 2016, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. Perhaps the most memorable result was the first to be declared – not only because of the enormity of the consensus expressed, but also because, somewhat counter intuitively, the result came from outside the United Kingdom altogether. Voters in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar—a rocky Mediterranean promontory, ceded to Great Britain by Spain in 1713— expressed an overwhelming 96% support for remaining within the European Union; the single largest majority of any of the returning areas in the EU referendum (Garcia, 2016). The Gibraltar result was a direct reflection of the critical importance of the EU for the lives, livelihoods and future prosperity of Gibraltar’s