•Œiâ•Žve Got a Feeling Weâ•Žre Not in Kansas, Anymore:•Š Cross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Peruvian Connection

VISIT CASA PRADOMAR, IN PUERTO COLOMBIA AND PARTY AT THE CARNAVAL DE BARRANQUILLA CHEF PIQUERAS ISIS ININ NEWNEW YORK!!!YORK!!! AND INVITES US TO A DELICIOUS TRIP TO PERÚ… CHEF GARZA THE SHARES HIS GRANNY RECIPE PERUVIAN FROM NUEVO CONNECTION LEON, MEXICO LOVE & ART... CASA WHAT’S FOOD GOT TO DO WITH IT? MEZCAL FROM OAXACA THE WALL TO THE LOWER SCRATCHER EAST SIDE A TALE ABOUT ROCOTO SEEDS, PISCO AND N.Y. Tourism Board THE PERUVIAN CONNECTION p14 p36 p52 p59 p63 THE WALL SCRATCHER SOULMATES: PERUVIAN CHEF TRY THE FAMOUS TRAVEL TO “THE Story by James Willimetz MEET CECILIA EMMANUEL RICE WITH CRADLE OF THE RICE & RYAN PIQUERAS CONFITED DUCK WITH DUCK” IN Interview by Interview by Original recipe by CHICLAYO, PERÚ Lynn Maliszewski Chris Yong-García Emmanuel Piqueras COVER PHOTO Ceviche Martini by chef Piqueras Panca Restaurant. Photo by Alejandra Martins A PERUVIAN MUST! CAUSA MARINA, WHICH COMBINES THE UNIQUE PERUVIAN YELLOW POTATO WITH DIFFERENT SEAFOOD SAUCES... By chef Piqueras Panca Restaurant. Photo by Alejandra Martins AN ICONIC PICTURE FROM “LOS AMANTES” Oaxaca-México (p. 42) Photo by: Rafael Vallejo. Artwork by: Guillermo Olguin CONTENT p9 p18 p30 CONTRIBUTORS: MAKE A MAGICAL TRIP ABUELA’S RECIPE MEET THE TEAM TO PUERTO COLOMBIA Original recipe by chef Story by Domingo Garza José Antonio Villaran p42 p70 A VISIT TO OAXACA- I LOVE BLUEBERRIES MEXICO, THROUGH CASA by Alejandra Martins MEZCAL IN NEW YORK Story by Joseduardo Valadéz Editor-in-Chief Chris Yong-García Associated Editors A DELICIOUS TRIP... Brian Waniewski José Antonio Villarán I’ve been asked so many times where I’m from, and I’ve asked myself that question a lot too. -

Over 1,000 Participating Online Stores

Over 1,000 Participating Online Stores Up to 26% of Each Purchase Benefits Nazareth Academy Grade School 1&1 Internet Inc. American Eagle Outfitters Bates Footwear BoatingSavings.com Canvas On Demand Coastal.com Dancing Deer Baking Co Earnest Sewn 1-800-Baskets.com American Express - Bath & Body Works Bobbi Brown Cosmetics Canvaspeople CoffeeForLess.com Danskin Eastbay 1-800-FLOWERS.COM Giftcards BBC America Shop Boden USA Car Parts Coffees of Hawaii Darphin Paris Easton 1-800-GET-LENS American Express Travel BCBG Body Central Carbonite Coldwater Creek DataJack Easy Comforts 1-800-GOT-JUNK? Americas Best Value Inn BCBGeneration Body Glove Mobile Cardstore Collections Etc. David's Cookies Easy Spirit 1-800-Pet Meds AmeriMark.com Beachbody BodyCandy Body Jewelry Care.com College Countdown Day-Timer EasyClickTravel.com 1-800-PetSupplies.com Amsterdam Printing Beaches Resorts Bogner CarMD Colorful Images DC Shoes eBags.com 100PercentPure Ancestry.com Beacon Hotel South Beach Bogs Footwear Carol Wright Gifts Comfortology DealChicken eBay UK 101Phones.com AndOtherBrands BeallsFlorida.com Bon-Ton Department Store Carol's Daughter CompUSA (In-Store DeepDiscount.com EC Research 123inkjets Ann Taylor Beauty.com Book Closeouts CarRentals.com Voucher) dELiA*s eCampus 123Print Anna's Linens BeautySage Booking.com Carson Pirie Scott Computer Geeks Dell Business eCOST 1800Flowers.ca Anne Klein bebe BookIt.com Carter's Constructive Playthings Dell Canada Eddie Bauer 2bStores Annie's Bed Bath & Beyond BookRenter Casa Contacts America Dell Home & Home -

1,600+ Participating Online Stores

1,600+ Participating Online Stores Up to 26% of Each Purchase Benefits Raleigh Boychoir 1&1 Internet Inc. Air France USA Ashley Stewart Best Deal Magazines Boutique To You Cat Footwear Compact Appliance Dan's Chocolates 1-800-Baskets.com AirTurn Ashro Best of Orlando Bowflex Catch Him & Keep Him Conrad Dancing Deer Baking Co 1-800-FLOWERS.COM AJ's Collection AsianFoodGrocer Best of Vegas Boxed Catherines Constant Contact Danskin 1-800-GET-LENS Alamo Rent a Car Astrogaming Best Western Brickhouse Security CB2 Constructive Playthings Darphin Paris 1-800-GOT-JUNK? ALDO AT&T BestBuy.com Broderbund CBTL The Coffee Bean & Contacts America David Yurman 1-800-Pet Meds Alex and Ani AT-A-GLANCE BestUsedTires Brooks Brothers Leaf Tea Cookies by Design David's Cookies 1-800-PetSupplies.com Algenist Athleta Betsey Johnson Brookstone CC Skye CookiesKids.com Day-Timer 100PercentPure Alibris Audible by Amazon Better Braces Brownells Celebrate Express Cooking.com Days Inn 101inks Alibris UK Augusta Active Better World Books BudgeCovers Century Novelty Coordinates Collection Dazadi 101Phones.com Alice & Trixie Autism Speaks Betty's Attic BuffaloJeans.com Chaco Corel Software Dazzlepro 11 Main AliExpress Auto Parts Warehouse Beyond the Rack Build Champion Cosabella Lingerie & DC Shoes 123-reg All About Dance Aveda BgB Supply Build-A-Bear Workshop Champion Naturals Fashion DealChicken 123inkjets ALLDATAdiy Avenue BH Cosmetics BuildASign Champion Performance Cost Plus World Market DeepDiscount.com 123Print Allen Edmonds Men's Shoe AVG Technologies Bicycle -

1,700+ Participating Online Stores

1,700+ Participating Online Stores Up to 26% of Each Purchase Benefits ViperBots Friends and Family 1&1 Internet Inc. Ahnu Ashley Stewart Beezid Booksamillion.com CarRentals.com Club Monaco CyberLink 1-800-Baskets.com Air Filters Delivered Ashro BeGood BookVIP CarrotInk CoachTube Cymax 1-800-FLOWERS.COM Air France USA Ashworth Golf Bellacor BoomStreet Carson Pirie Scott Coastal.com D'Artagnan 1-800-GET-LENS AirTurn AsianFoodGrocer BelleChic Boscov's Carter's Coffee Wholesale USA Daily Burn 1-800-GOT-JUNK? Alamo Rent a Car AT&T Ben Meadows Bose Canada Casa Coffee.org Dancing Deer Baking Co 1-800-Pet Meds ALDO AT-A-GLANCE Benefit Cosmetics Bose.com Cascio Interstate Music CoffeeForLess.com Danskin 1-800-PetSupplies.com Alex and Alexa Athleta BenQ America Bosky Optics Casetify Coggles Darphin Paris 101inks Alex and Ani Auburn University - Bentley Leathers Boston Proper Casual Male Gift Card Collections Etc. David's Cookies 101Phones.com Algenist Bookstore Ander's Bergdorf Goodman Boston Store CashStar from Colorful Images DAWGS 123-reg Alibaba Augusta Active Bergner's Botanic Choice Herbs & Casual Male XL Compact Appliance Day-Timer 123inkjets Alibris Auto Europe Car Rental Best Cigar Prices Vitamins Cat Footwear Compass Hospitality Days Inn 123Print Alibris UK Auto Parts Warehouse Best Deal Magazines Bourbon & Boots Catherines Condor Airlines Dazadi 180 Nutrition Alice & Trixie Aveda Best of Orlando Bowflex Caudalie Conrad Dazzlepro 1800AnyLens.com AliExpress Avenue Best of Vegas Boxed CB2 Constant Contact DC Shoes 1800Flowers.ca All About -

Winter 2018 Winter Abloom

Winter 2018 Winter Abloom Our Winter 18 Collection explores ethnographic textile traditions from around the world—from Indian saris to Andean mantas, from rhythmic African fabric to Japanese kimonos. Available September, 2018 3 Magnolia Skirt, Chalet Cowlneck, Vallnord Fur Hat. 2 Annecy Coat, Paxton Hoodie, Cinched Cuff Pants. 3 4 Modernist Dress. 5 Guthrie Pullover, Tweeded Grey Scarf. 6 7 Vicarage Coat, Tweed T-Neck, Motorcycle Pants. 8 Luxe Waffle Tunic, Spa Leggings, Valmala Scarf. 9 Kelmscott Knit Coat, Black Extreme T-Neck, Velveteen 5-Pocket Jeans. Amasya Dress, Gelsey Cardigan, Heart Charm Earrings, Colca Canyon Bracelets. 10 Nunavut Blanket Coat, Katherine Tunic, Velveteen 5-Pocket Jeans, Drifter Boots. 11 12 Khokhloma Reversible Ruana, Black Extreme T-Neck, Black Velveteen 5-Pocket Jeans, Drifter Boots. 13 14 Wyatt Dress, Cocoa Floral Bandana, Cortina Boots. 15 Colca Canyon Dress, Arles Scarf, Cortina Boots. 16 Sigrid Cardigan, Vintage Greta Tee, Cinched Cuff Pants, Bordeaux Chiffon Lariat. 17 Halstead Cardigan, Sasha Scarf, Port Long Tank, Velveteen 5-Pocket Jeans. 18 Elspeth Dress, Grey Alpaca Fur Pull-Through Scarf. 19 Alpaca Flyaway Tunic, Marble Heather Long Tank, Dove Motorcycle Pants, Cabled Legwarmers, Alhambra Hoops. 20 Stowe Pullover, Dove Motorcycle Pants, Grey Cabled Legwarmers, Moon and Stars Necklace. 21 Merano Pullover, Dove Motorcycle Pants, Santa Clara Knit Alpaca Hat. 22 Windsor Dress, Vallnord Fur Hat, Cognac Vercelli Leather Gloves. 23 24 Tapestry Tweed Jacket, Tapestry Tweed Skirt, Moon and Stars Necklace. 25 26 27 Woodlands Hooded Cardigan, Olive Heather Extreme T-Neck, Moss Velveteen 5-Pocket Jeans, Hanover Knit Hat, Valmala Scarf. 28 Bandana Pima Skirt, Boyfriend Shirt, Tribal Amulet Necklace. -

2018 Google Economic Impact Report

Economic Impact Repor United States 2018 Contents 2 Introduction 3 National numbers 5 Where we get the numbers 7 Our tools and programs 11 Repors by state 69 References The web is connecting customers with businesses of all kinds, and Google is helping. The internet is connecting communities of all sizes, Each month, we drive over 1 billion connections for creating exciting new possibilities for businesses across businesses nationwide, like phone calls or online the United States. Providing digital tools and resources reservations. We’re also connecting businesses with that help American business owners make the most of customers overseas; in 2018 more than 35% of clicks for these connections is an important part of what I do. As the U.S. business advertising on Google came from places daughter of a small business owner, helping hardworking outside the U.S. Americans like my parents makes this work particularly meaningful to me. We’re connecting with business owners in their hometowns through Grow with Google, our initiative to It was incredibly rewarding this past year to see the power of create economic opportunity for all Americans. Since technology at work for so many different kinds of businesses. 2017, we’ve provided over 3 million people with digital It helps a brick-and-mortar business like Amini’s — a specialty skills training and upskilling opportunities, helping them furniture store in St. Louis, Missouri — build an e-commerce prepare for work, fnd jobs, and grow their businesses. strategy that puts its website at the center of its work. It lets This includes hosting workshops and classes in more a rural business like Fuller’s Sugarhouse share its maple than 40 cities and towns across the country. -

Spring 2016 Peruvianconnection.Com

Spring 2016 peruvianconnection.com Since 1976, Peruvian Connection has made ethnographic textiles the point of reference for its artisan-made, luxury fiber collections. In addition to the label’s signature knitwear, it offers a range of romantic dresses, superbly tailored outerwear and unique, handcrafted accessories, all exclusively designed by and for Peruvian Connection. A complete catalogue of the Spring 2016 collection is available by request. Jazmín Skirt L-722192 $179, Porto Pullover L-741662 $149, Apache Bucket Bag L-255002 $239, For additional images, product details and sample requests, Costa Sun Hat L-Y80109 $99, Oxidized Rings L-V70187 $39, contact Brittany Banion, 773.661.0700, [email protected] Bohème Tassel Earrings L-D90019 $110. 2 3 Kashkai Drape Vest L-531112 $318, Valencia Dress L-630742 $89. Chaska Mother-of-Pearl Bracelet L-L81979 $49, Chaska Seaside Bracelet L-L81989 $49. 4 5 Wyatt Duster L-Z80029 $289. Madeira Dress L-H80939 $199. 6 7 Becca Cardigan L-741682 $169, Ferrara Bag L-X30164 $329. Fuji Silk Jacket L-M50429 $398, Printmaker Pants L-B30999 $139, Kana Earrings L-F90387 $18. Inglenook Capelet J-203061 $179, Grey Skinny Jeans J-L30152 $149. 8 9 , Scoopneck Tee L-322142 $39, A-Line Skirt L-322152 $59, Bronze Leather Tie Belt L-X40044 $59, Miniature Landscape Necklace, L-D00029 $349. Esperanza Cardigan L-620522 $229, Madder Red Chandra Pants L-J90239 $159. 10 11 Dakota Cardigan L-243502 $179, Wedgewood Double-Layer Dress L-190912 $99, Cody Crocheted Belt L-255042 $129. Antibes Dress L-322122 $69, Deco Leafworks Scarf L-K10362 $69. -

Fall 2019 Peruvianconnection.Com

Fall 2019 peruvianconnection.com artful PATTERNS BRING A SENSE OF joy TO forever SILHOUETTES Our Fall '19 Collection explores ethnographic textile traditions from around the world—from Asian florals to Moroccan geometrics, from Andean mantas to African mud cloth. Available July, 2019 Persian Brocade Cami and Maxi-Skirt, Hokusai Knit Coat, Gaucho Hat, Chiclayo Belt. 2 3 Windward Pullover, Rock Point Skirt, Rancher Hat, Volusia Suede Tassel Necklace. 4 Imani Sheath, Gemini Cocktail Ring. 5 6 Declan Reversible Coat, Checked Ryder Pants, Poppy/Plaid Bandana, Teardrop Chain Hoops. 7 Dylan Pullover, Checked Ryder Pants. 8 sublimely soft STRIPES 9 Brattleboro Coat, Kate 5-Pocket Jeans, Long Ribbed Tee, Floralinda Bandana. 10 11 12 Southport Poncho Pullover, Lucullus Printed Spa Leggings, Demi-Hoop Brass Bead Earrings, Piura Bracelet/Choker. 13 Osterley Reversible Coat, Phoenix Burnout Top, Bonded Leather Leggings, Midnight Floral Bandana. 14 Andover Dress, Black Left Bank Wool Beret. 15 brilliant COLOR A MIX OF fabrics 16 Sylphide Dress, Pecos Boots, Rock Hound Bracelet, Seraglio Earrings. 17 poetry MEETS GEOMETRY 18 Clarice Blouse, Gemini Cocktail Ring, Painted Desert Wrap, Barnwood Zoe Velveteen Jeans, Talara Belt, Demi-Hoop Brass Bead Earrings. 19 Barrakka Dress, Redrock Zoe Velveteen Jacket, Anastasia Lariat Necklace. 20 21 Kyoto Forest Dress, Gaucho Hat, Pecos Boots, Demi-Hoop Brass Bead Earrings. 22 good boots SURVIVE TRENDS 23 Folklorica Dress, Black Silk Slip, Horn Fibonacci Hoops. 24 craftsmanship LASTS forever 25 Jammu Knit Coat, Peony Jogger Pants, Tulipan Shawl, Q’ero Belt, Ayacucho Belt. 26 fearless MIX OF PATTERN, TEXTURE & COLOR 27 Cabled Trellis Tunic, Black Motorcycle Pants. -

The Gift Collection Since 1976, Peruvian Connection Has Made Ethnographic Textiles the Point of Reference for Its Artisan-Made Collections

The 2018 Gift Collection The Gift Collection Since 1976, Peruvian Connection has made ethnographic textiles the point of reference for its artisan-made collections. In addition to the label’s signature alpaca and pima cotton knitwear, it offers a range of superbly tailored outerwear and luxurious basics, all designed and made exclusively for Peruvian Connection. Vintage Brocade Dress, Cayenne Vercelli Gloves, Cayenne Leather Obi Sash 2 Zermatt Shearling Coat, Brocade Moto Pants, Espresso Vallnord Hat 3 Brimfield Henley Carmina Reversible Ruana, Black Bennington T-Neck, Black Lace Crocheted Earrings 4 Black Lace Crocheted Earrings, Madero Maxi-Dress, Black Vallnord Hat 5 Rambler Skirt, Edie Pullover, Vaquero Fur Felt Hat, Yavari Belt 6 Ayaviri Skirt, Long Ribbed Tee, Vaquero Fur Felt Hat, Cuzco Motif Belt 7 Megève Pullover, Tillamook Capelet 8 Aubade Skirt, Stella Pullover 9 Portree Pullover, Tweeded Alpaca Beret 10 Mackinac Capelet, Layering Tee, Mackinac Pompom Hat Berkshires Vest, Eloise Tunic, Riley Hat 11 Colonial Flower Earrings, Chalet Cowlneck, Giselle Skirt, Cuzco Motif Belt 12 Highlands Shirt, Eddleston Skirt, Vaquero Fur Felt Hat 13 Ginevra Dress, Vallnord Fur Hat, Alpaca Fur Hand Muff 14 Glen Plaid Ruana, Fairfield Tunic, Velveteen Jeans, Chantini Necklace 15 Balie Tunic, Santa Clara Hat Finnia Lace Jacket, Vallnord Fur Hat, Velveteen Jeans 16 Merrivale Poncho, Velveteen Jeans, Castello Gloves Lidia Dress, Bennington T-Neck, Fur Pompom Hat 17 Keiko Knit Coat, Fairfield Tunic, Spa Leggings, Vaquero Hat 18 Marrakesh Poncho, Bennington -

Writer's Cabin 2017

Writer’s Cabin 2017 Ketchum, Idaho Just in time for the holidays, our newest collection showcases soft, lofty alpaca— in warm sweaters, snuggly coats and artisan-made accessories that will elevate any look. This imaginative collection offers a mother lode of ideas for all the free spirits on your list. Collection available November 2017 peruvianconnection.com Holbrook Alpaca Blend Tunic, Velveteen 5-Pocket Jeans, Huntress Boots. 2 3 Mercado AlpacaTunic, Spa Leggings, Wanderer Alpaca Legwarmers, Moccasin Boots. 4 5 Going off the Grid Lorenna Pima Dress, Jutland Alpaca Legwarmers. Highline Alpaca Blend Cardigan, Shale Pinstripe Pants, Left Bank Beret. 6 7 Edelweiss Alpaca and Wool Cardigan, Extreme T-Neck, Inti Earrings. 8 9 Bastia Pima T-Neck, Ashcroft Alpaca Coat, Snow Creek Legwarmers, Ashcroft Alpaca Coat, Creek Snow Inti Earrings. T-Neck, Bastia Pima 10 11 Snow Creek Alpaca Capelet, Fingerless Gloves and Legwarmers, Long Ribbed Tee, Velveteen 5-Pocket Jeans, Moccasin Boots. 12 13 Imogene Pima Cardigan, Leather Pencil Skirt, Adler Fedora, Alpaca Fur Patchwork Bag. Exceptional Artisan Apparel 14 15 Lucca Viscose Shirt, Pima Skirt, Belt, and Ring Lariat. Zendaya Spike Frontera 16 17 Pocatello Alpaca/Wool Blanket Vest, Bennington Pima T-Neck, Velveteen 5-Pocket Jeans, Stowe Alpaca Hat. Frisco Alpaca/Wool Tweed Coat, Velveteen 5-Pocket Jeans, Elena Shawl, Vercelli Leather Gloves. 18 19 Art Deco Blanket Pima/Alpaca/Wool Coat, Vercelli Leather Gloves, Beaded Trapeze Earrings. 20 21 Estancia Alpaca Blend Pullover, Chimu Scarf, Adler Fedora. 22 Earrings. Trapeze Belt, Horn Fedora, Allie Frontera T-Neck, Alpaca Cardigan, Sawtooth Extreme 23 Royal Alpaca Ruana, Oriental Vine Shawl, Vercelli Leather Gloves. -

2,300+ Participating Online Stores

2,300+ Participating Online Stores Up to 26% of Each Purchase Benefits Bridges Oregon 0cm Agoda AnchorFree Hotspot Shield b-glowing Bench Boden USA buybuy Baby CBD Essence 1-800 CONTACTS Agora Cosmetics VPN Elite Baabuk Sarl Benefit Cosmetics Bodum BuyWake.com CBD Oil Solutions 1-800-Baskets.com AHAVA Andrew Marc Babo Botanicals BenQ America Body Spartan Cabany co CBTL The Coffee Bean & 1-800-FLOWERS.COM Aidance Scientific Angels' Cup Baby Quasar Bentley Leathers BodyBoss Caesars Entertainment Leaf Tea 1-800-GET-LENS Air Filters Delivered Animoto Back in the Saddle Beretta USA BodyGuardz City Atlantic Celestia 1-800-GOT-JUNK? Air-Purifiers-America Anjay's Designs Backcountry.com Bergdorf Goodman Bodyography Caesars Rewards Certblaster 1-800-Pet Meds Airocide Ann Taylor BackJoy Besame Cosmetics Bogner Cafe Britt Gourmet Coffee Certified Piedmontese 1-800-PetSupplies.com Airport Parking Annie's BagAmour Box Best Bully Sticks Bogs Footwear Cafe Joe Chaco 100% Pure Airport Parking Antop Antenna Inc. Baggallini Best Buy Eye Glasses Bokksu Cakeflix Champion 101Phones.com Reservations Anytime Costumes Bakblade Best Choice Products Bombinate Calendars.com Chantelle Lingerie 123-reg AirTurn Aphrodite's Bake Me a Wish Best Cigar Prices Bonafide California Chamber of Chaparral Motorsports 123inkjets Airvape Apollo Box Baked by Melissa Best Western Bonanza Commerce Chapters.Indigo.ca 123Print AJ Madison Apple Balance by Bistro MD BestBuy.com Bonobos Caliper CBD Charles & Colvard 180 Nutrition Alala Apple Canada Balance of Nature BestUsedTires Boob -

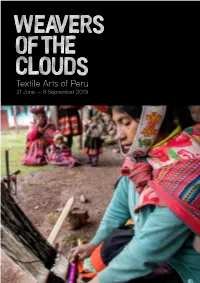

FTM-WOTC-Handout-V5.Pdf

Credits Guest Curator: Hilary Simon With special thanks to: Head of Exhibitions: Alice Viera Albergaria Costa Borges Dennis Nothdruft Annie Hurlbut, Peruvian Connection Exhibition Design: Beth Ojari Armando Andrade Garment Mounting and Conservation: Camilo Garcia, IAG Cargo Gill Cochrane Carlos Agusto Dammert, Hellmann Exhibitions Coordinator: Marta Martin Soriano Worldwide Logistics Caryn Simonson, Chelsea College of Art Curator of ‘A Thread: Contemporary Art of Peru’: H.E Juan Carlos Gamarra Ambassador Claudia Trosso of Peru to Great Britain Jaime Cardenas, Director of Peru Trade Graphic Design: Hawaii and Investment Office Set Build and Installation: Setwo Ltd Leonardo Arana Yampe Graphic Production: Display Ways Mari Solari Handout Design: Madalena Studio Martin Morales Peruvian Embassy Head of Commercial and Operations: Promperú Melissa French Samuel Revilla and Luis Chaves, KUNA Operations Manager: Charlotte Neep Soledad Mujica Press and Marketing Officer: Philippa Kelly Susana de la Puente Front of House Coordinator: Vicky Stylianides Retail and Events Officer: Sadie Doherty Gallery Invigilation: Abu Musah PR Consultant: Penny Sychrava WEAVERS OF THE CLOUDS is a Fashion and Textile Museum exhibition Cover: ©Awamaki/Brianna Griesinger. Opposite: ©Mel Smith Opposite: Griesinger. ©Awamaki/Brianna Cover: Glossary of Peruvian Costume Women’s Traditional Dress Men’s Traditional Dress Ajotas – sandals made from recycled truck tyres. Ajotas – sandals made from recycled truck tyres. Camisa/blusa – a blouse. Buchis – short pants adapted from Spanish costume, which, Chumpi – a woven belt. depending on the area, come to the knee or a little longer. Juyuna – wool jackets that are worn under the women’s Centillo – finely decorated hat bands. shoulder cloths, with front panels decorated with white buttons.