Money Neutrality Long Run and Short

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine

with Open Texts Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine VERSION 2017 – REVISION B ADAPTABLE | ACCESSIBLE | AFFORDABLE Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-SA) advancing learning Champions of Access to Knowledge OPEN TEXT ONLINE ASSESSMENT All digital forms of access to our high- We have been developing superior on- quality open texts are entirely FREE! All line formative assessment for more than content is reviewed for excellence and is 15 years. Our questions are continuously wholly adaptable; custom editions are pro- adapted with the content and reviewed for duced by Lyryx for those adopting Lyryx as- quality and sound pedagogy. To enhance sessment. Access to the original source files learning, students receive immediate per- is also open to anyone! sonalized feedback. Student grade reports and performance statistics are also provided. SUPPORT INSTRUCTOR SUPPLEMENTS Access to our in-house support team is avail- Additional instructor resources are also able 7 days/week to provide prompt resolu- freely accessible. Product dependent, these tion to both student and instructor inquiries. supplements include: full sets of adaptable In addition, we work one-on-one with in- slides and lecture notes, solutions manuals, structors to provide a comprehensive sys- and multiple choice question banks with an tem, customized for their course. This can exam building tool. include adapting the text, managing multi- ple sections, and more! Contact Lyryx Today! [email protected] advancing learning Principles of Microeconomics an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine Version 2017 — Revision B BE A CHAMPION OF OER! Contribute suggestions for improvements, new content, or errata: A new topic A new example An interesting new question Any other suggestions to improve the material Contact Lyryx at [email protected] with your ideas. -

< LRMC, MR = SRMC Iii) SRAC < LRAC, SRMC > LRMC

Econ 100A Fall 2001 Prof. Daniel McFadden Problem Set 8 1. True/False: state your reasons clearly and succinctly. a) A profit-maximizing firm will always minimize costs. True. b) In the long run a firm always operates at the minimum level of average costs for the optimally sized plant to produce a given amount of output. False. 2. Assume downward sloping or flat demand and a U-shaped LRAC curve. In each of the following situations, determine graphically and/or verbally: a) Does the firm have the cost-minimizing amount of capital given its output level? If not, should the firm increase or decrease its amount of capital given its output? b) Does the firm have the profit maximizing level of output given its amount of capital? If not, should the firm increase or decrease its level or output, given its capital? If the situation is impossible, state why. Answers: first, it is to be understood that capital input is here regarded as the fixed costs---fixed in the short run, that is. So the two questions for each case come down to your judgment in the short term and long term. Secondly, refer to Fig.21.6 and 21.10 for a graphical understanding of the explanation. i) SRAC > LRAC, SRMC > LRMC, MR = SRMC MR=SRMC shows that the firm is at an output level that maximizes the profit, given its capital in the short term. However, because SRMC>LRMC and SRAC>LRAC (See Fig. 21.10), the amount of capital is not optimized to minimize costs at the present output level. -

ECON 110 Principles of Macroeconomics

South Central College ECON 110 Principles of Macroeconomics Common Course Outline Course Information Description Macroeconomics is the study of issues that affect whole economies, including economic growth, employment levels, management of the money supply, international trade, and economic instability. The course will examine tools governments can use to stabilize and grow economies, as well as controversies surrounding their use. Prerequisites: READ0090 with a grade of C or Higher or a minimum score of 78 on the Accuplacer Reading Comprehension test. This class satisfies MnTC Goal Area 5 (History and the Social and Behavioral Sciences) and MnTC Goal Area 9 (Ethical and Civic Responsibility). Total Credits 3.00 Total Hours 48.00 Types of Instruction Instruction Type Credits/Hours Lecture 3 Pre/Corequisites READ0090 with a grade of C or Higher or a minimum score of 78 on the Accuplacer Reading Comprehension test. Institutional Core Competencies 1 Analysis and inquiry: Students will demonstrate an ability to analyze information from multiple sources and to raise pertinent questions regarding that information. 2 Civic knowledge and engagement- local and global: Students will understand the richness and challeng e of local and world cultures and the effects of globalization, and will develop the skills and attitudes to function as “global citizens." 3 Teamwork and problem-solving: Students will demonstrate the ability to work together cohesively with diverse groups of persons, including working as a group to resolve any issues that arise. Course Competencies 1 Apply the economic method. Learning Objectives Define Economics. Common Course Outline September, 2016 Apply the scientific method in economics. Demonstrate scarcity, opportunity costs, and economic growth with the production possibility curve model. -

A Review of Microeconomic Theory

Chapter 2 A REVIEW OF MICROECONOMIC THEORY “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. It is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.” John Maynard Keynes, THE GENERAL THEORY OF EMPLOYMENT, INTEREST, AND MONEY (1936) “In this state of imbecility, I had, for amusement, turned my attention to political economy.” Thomas DeQuincey, CONFESSIONS OF AN ENGLISH OPIUM EATER (18– –) “Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship be- tween ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.” Lionel Charles Robbins, Lord Robbins, AN ESSAY ON THE NATURE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF ECONOMIC SCIENCE (1932) HE ECONOMIC ANALYSIS of law draws upon the principles of microeco- Tnomic theory, which we review in this chapter. For those who have not studied this branch of economics, reading this chapter will prove challenging but useful for understanding the remainder of the book. For those who have already mastered microeconomic theory, reading this chapter is unnecessary. For those readers who are somewhere in between these extremes, we suggest that you begin reading this chapter, skimming what is familiar and studying carefully what is un- familiar. If you’re not sure where you lie on this spectrum of knowledge, turn to the questions at the end of the chapter. If you have difficulty answering them, you will benefit from studying this chapter carefully. 13 14 CHAPTER 2 A Review of Microeconomic Theory I. OVERVIEW: THE STRUCTURE OF MICROECONOMIC THEORY Microeconomics concerns decision-making by individuals and small groups, such as families, clubs, firms, and governmental agencies. -

New-Keynesian Economics: an AS-AD View

Research in Economics 69 (2015) 503–524 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Research in Economics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rie New-Keynesian economics: An AS–AD view Pierpaolo Benigno LUISS Guido Carli, Italy article info abstract Article history: A simple New-Keynesian model is set out with AS–AD graphical analysis. The model is Received 26 June 2015 consistent with modern central banking, which targets short-term nominal interest rates Accepted 13 July 2015 instead of money supply aggregates. This simple framework enables us to analyze the Available online 6 August 2015 economic impact of productivity or mark-up disturbances and to study alternative Keywords: monetary and fiscal policies. Aggregate supply The framework is also suitable for studying a liquidity-trap environment, the econo- Aggregate demand mics of debt deleveraging, and possible solutions. Stabilization Policies The impact of the fiscal multipliers on output and the output gap can be quantified. Inflation Targeting During normal times, a short-run increase in public spending has a multiplier less than Debt Deleveraging one on output and a much smaller multiplier on the output gap, while a decrease in short- Liquidity trap run taxes has a positive multiplier on output, but negative on the output gap. When the economy is depressed because some agents are deleveraging, fiscal policy is more powerful and the multiplier can be quite big. In the AS–AD graphical view, optimal policy simplifies to nothing more than an additional line, IT, along which the trade-off between the objective of price stability and that of stabilizing the output gap can be optimally exploited. -

The Model SRAS – Short-Run Aggregate Supply APL LRAS SRAS LRAS – Long-Run Aggregate Supply

Ref: A981896 Stage 2 Economics (from 2021) Aggregate Demand Aggregate Supply Model – Monetarist Perspective Some of this material has been sourced from: Tragakes E, (2012) Economics for the IB Diploma Second Addition Cambridge University Press The basis of this model is in the belief that factor markets are flexible (like product markets) and will adjust to disturbances in product markets. Thus, there is a distinction between the long-run and short-run. The short-run - (in macroeconomics) the period of time when prices of resources are constant or inflexible but product prices (average price levels) can adjust The long run - (in macroeconomics): the period of time when the prices of all resources, including the price of labour (wages) are flexible and change with changes in the average price level The Model SRAS – Short-run Aggregate Supply APL LRAS SRAS LRAS – Long-run Aggregate Supply AD – Aggregate Demand RGDP – Real Gross Domestic Product Ple APL – Average Price Levels (also accepted: GPL – General Price Levels or PL – Price Levels) Yp – Long-run Potential Level of Output (Full Employment Level of Output: LRAS = SRAS) AD Yp RGDP Ye – Short-run Equilibrium Level of Output Ye (Ye = SRAS) Ple – Short-run Level of Average Prices Alternate Short-run Positions Deflationary Gap Situation where Ye<Yp Inflationary Gap Situation where Ye>Yp APL LRAS APL LRAS SRAS SRAS Ple Ple AD AD Yp Ye Yp RGDP Ye RGDP Ref: A981896 Short-run to Long-run Change Deflationary Gap Inflationary Gap SRAS1 APLPe LRAS APL LRAS SRAS SRAS Ple1 SRAS1 Ple Ple Ple1 AD AD Yp Ye RGDP Ye Yp RGDP Ye1 Ye1 In short-run Ye<Yp and average price levels have In short-run Ye>Yp and average price levels have fallen as has output. -

Nber Working Paper Series the Harrod-Balassa

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE HARROD-BALASSA-SAMUELSON HYPOTHESIS: REAL EXCHANGE RATES AND THEIR LONG-RUN EQUILIBRIUM Yanping Chong Òscar Jordà Alan M. Taylor Working Paper 15868 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15868 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2010 Jordà is grateful for the support from the Spanish MICINN National Grant SEJ2007-6309 and the hospitality of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco during preparation of this manuscript. Taylor also gratefully acknowledges research support from the Center for the Evolution of the Global Economy at the University of California, Davis. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by Yanping Chong, Òscar Jordà, and Alan M. Taylor. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Harrod-Balassa-Samuelson Hypothesis: Real Exchange Rates and their Long-Run Equilibrium Yanping Chong, Òscar Jordà, and Alan M. Taylor NBER Working Paper No. 15868 April 2010 JEL No. F31,F41 ABSTRACT Frictionless, perfectly competitive traded-goods markets justify thinking of purchasing power parity (PPP) as the main driver of exchange rates in the long-run. But differences in the traded/non-traded sectors of economies tend to be persistent and affect movements in local price levels in ways that upset the PPP balance (the underpinning of the Harrod-Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis, HBS). -

Guy Debelle and Stanley Fischer Discussion / 222 Robert E

Gaals, Guidelines, and Constraints Facing Manetary Palicymakers Goals, Guidelines, and Constraints Facing Monetary Policymakers Proceedings of a Conference Held at North Falmouth, Massachusetts June 1994 Jeffrey C. Fuhrer, Editor Sponsored by: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Contents Goals, Guidelines, and Constraints Facing Monetary Policymakers: An Overview / Jeffrey C. Fuhrer How Efficient Has Monetary Policy Been? The Inflation/Output Variability Trade-off Revisited / 21 John B. Taylor Discussion / 39 Laurence M. Ball Optimal Monetary Policy and the Sacrifice Ratio / 43 Jeffrey C. Fuhrer Discussion / 70 N. Gregory Mankiw Summary Discussion / 76 Martin S. Eichenbaum Comparing Direct and Intermediate Targeting Monetary Aggregates Targeting in a Low-Inflation Economy / 87 William Poole Discussion / 122 Benjamin M. Friedman Donald L. Kohn Lessons from International Experience Strategy and Tactics of Monetary Policy: Examples from Europe and the Antipodes / 139 Charles A.E. Goodhart and Josd Vi~ials Discussion / 188 Richard N. Cooper How Independent Should a Central Bank Be? / 195 Guy Debelle and Stanley Fischer Discussion / 222 Robert E. Hall How Can Monetary Policy Be Improved? Panel Discussion / 229 Paul A. Samuelson James Tobin Robert J. Barro Lyle E. Gramley Bennett T. McCallum About the Authors / 251 Conference Participants / 257 Goals, Guidelines, and Constraints Facing Monetary Policymakers This conference addressed three broad questions about the conduct of monetary policy. First, how efficiently has U.S. policy balanced the goals of price stability and full employment? Second, have rapidly changing financial markets made the use of intermediate targets, such as monetary aggregates, obsolete? Third, what can domestic policymakers learn from the tactics and strategies employed by foreign central banks? A concluding panel suggested improvements to monetary policy, in light of the conclusions drawn in the previous sessions. -

Short Run Gravity

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES SHORT RUN GRAVITY James E. Anderson Yoto V. Yotov Working Paper 23458 http://www.nber.org/papers/w23458 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2017 The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by James E. Anderson and Yoto V. Yotov. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Short Run Gravity James E. Anderson and Yoto V. Yotov NBER Working Paper No. 23458 May 2017 JEL No. F10,F14,F15 ABSTRACT Short run gravity is a geometric weighted average of long run gravity and bilateral capacity. The model features (i) joint trade costs endogenous to bilateral volumes, (ii) long run gravity as a limiting case of efficient investment in bilateral capacities, (iii) a structural ratio of short run to long run trade elasticities equal to a micro-founded buyers' incidence elasticity, and (iv) tractable short and long run models of the extensive margin. Application to manufacturing trade of 52 countries during the globalization period 1988-2006 strongly supports the model. Results solve several time invariance and trade elasticity puzzles in the literature. James E. Anderson Department of Economics Boston College Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 and NBER [email protected] Yoto V. -

Examining the Firm's Long-Run and Short-Run Adjustments to a Price Increase

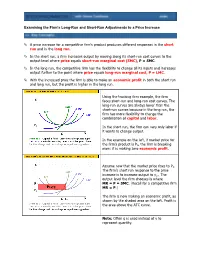

Examining the Firm's Long-Run and Short-Run Adjustments to a Price Increase A price increase for a competitive firm’s product produces different responses in the short run and in the long run. In the short run, a firm increases output by moving along its short-run cost curves to the output level where price equals short-run marginal cost (SMC), P = SMC. In the long run, the competitive firm has the flexibility to change all its inputs and increases output further to the point where price equals long-run marginal cost, P = LMC. With the increased price the firm is able to make an economic profit in both the short run and long run, but the profit is higher in the long run. Using the trucking firm example, the firm faces short-run and long-run cost curves. The long-run curves are always lower than the short-run curves because in the long run, the firm has more flexibility to change the combination of capital and labor. In the short run, the firm can vary only labor if it wants to change output. In the example on the left, if market price for the firm’s product is P0, the firm is breaking even: it is making zero economic profit. Assume now that the market price rises to P1. The firm’s short run response to the price increase is to increase output to y1s. The output level the firm chooses is where MR = P = SMC. (Recall for a competitive firm MR = P.) The firm is now making an economic profit, as shown by the shaded area on the left. -

Welfare Economics and the Theory of Optimum Public Utility

WELFARE ECONOMICS AND THE THEORY OF OPTIMUM PUBLIC UTILITY PRICING AND THEIR PRACTICAL APPLICATION WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO FEDERAL TRANSPORTATION POLICY DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State Universi ty By Thomas Anton Martinsek, A. B., M. A The Ohio State University 1956 Approved by: Adviser Department of Economics TABLE OP CONTENTS Page LIST OP ILLUSTRATIONS v. Part One WELFARE ECONOMICS AND EQUILIBRIUM CONDITIONS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . <.......................... 2 II. ECONOMIC WELFARE CRITERIA .................... >■ 8 The Nature of Welfare Economics: The Social Welfare Function Efficiency of Production and Consumption: Marginal Conditions for an Optimum Reorganizations: The Compensation Principle Welfare Measures To Be Used in the Study III . LAWS OF COSTS AND R E T U R N S ....... 44 Firm Cost Patterns Industry Supply Patterns Summary and Conclusi ons IV. EQUILIBRIUM CONDITIONS AND MAXI MUM WELFARE... 84 Equilibrium of the Firm Equilibrium of the Industry Summary and Conclusions Part Two THE THEORY OF PUBLIC UTILITY PRICING V. THE CRITERIA FOR PUBLIC UTILITY CLASSIFICATION ................................. 122 The Legal Criteria for Public Utility Regulation An Economic Criterion for Public Utility Classification Existing Public Utility Control In the Light of the Postulated Economic Definition VI, THE DETERMINATION OF LONG-RUN PUBLIC UTILITY PRICES ................................. 147 The Possible Choices Payments Necessary with Marginal-Cost Pricing Conclusions ii Chapter - Page \ VTI. THE SHORT-RUN AND OTHER PROBLEMS. S OP PUBLIC UTILITY PRICING . .'................ $. 178 Short-Run Public Utility; Pricing New and Expanding Industries Dyinp; and Contracting Industries Conclusions Part Three THEORY AMD PRACTICE IN PUBLIC UTILITY REGULATION VIII. -

Long-Run and Short-Run Consumption Asymmetries in a Non-Linear Error

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics van Treeck, Till Working Paper Asymmetric income and wealth effects in a non- linear error correction model of US consumer spending IMK Working Paper, No. 06/2008 Provided in Cooperation with: Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) at the Hans Boeckler Foundation Suggested Citation: van Treeck, Till (2008) : Asymmetric income and wealth effects in a non- linear error correction model of US consumer spending, IMK Working Paper, No. 06/2008, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Institut für Makroökonomie und Konjunkturforschung (IMK), Düsseldorf, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-20080818157 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/105900 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.