Men at Work: Masculinity, Work and Class in King of the Coral Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

4BH 1000 Best Songs 2011 Prez Final

The 882 4BH1000BestSongsOfAlltimeCountdown(2011) Number Title Artist 1000 TakeALetterMaria RBGreaves 999 It'sMyParty LesleyGore 998 I'llNeverFallInLoveAgain BobbieGentry 997 HeavenKnows RickPrice 996 ISayALittlePrayer ArethaFranklin 995 IWannaWakeUpWithYou BorisGardiner 994 NiceToBeWithYou Gallery 993 Pasadena JohnPaulYoung 992 IfIWereACarpenter FourTops 991 CouldYouEverLoveMeAgain Gary&Dave 990 Classic AdrianGurvitz 989 ICanDreamAboutYou DanHartman 988 DifferentDrum StonePoneys/LindaRonstadt 987 ItNeverRainsInSouthernCalifornia AlbertHammond 986 Moviestar Harpo 985 BornToTry DeltaGoodrem 984 Rockin'Robin Henchmen 983 IJustWantToBeYourEverything AndyGibb 982 SpiritInTheSky NormanGreenbaum 981 WeDoIt R&JStone 980 DriftAway DobieGray 979 OrinocoFlow Enya 978 She'sLikeTheWind PatrickSwayze 977 GimmeLittleSign BrentonWood 976 ForYourEyesOnly SheenaEaston 975 WordsAreNotEnough JonEnglish 974 Perfect FairgroundAttraction 973 I'veNeverBeenToMe Charlene 972 ByeByeLove EverlyBrothers 971 YearOfTheCat AlStewart 970 IfICan'tHaveYou YvonneElliman 969 KnockOnWood AmiiStewart 968 Don'tPullYourLove Hamilton,JoeFrank&Reynolds 967 You'veGotYourTroubles Fortunes 966 Romeo'sTune SteveForbert 965 Blowin'InTheWind PeterPaul&Mary 964 Zoom FatLarry'sBand 963 TheTwist ChubbyChecker 962 KissYouAllOver Exile 961 MiracleOfLove Eurythmics 960 SongForGuy EltonJohn 959 LilyWasHere DavidAStewart/CandyDulfer 958 HoldMeClose DavidEssex 957 LadyWhat'sYourName Swanee 956 ForeverAutumn JustinHayward 955 LottaLove NicoletteLarson 954 Celebration Kool&TheGang 953 UpWhereWeBelong -

Jamestown Duo Master Song List 2017

SONG ARTIST: Africa Toto All About That Bass Meghan Trainor Alone Heart A Million Reasons Lady Gaga Are You Gonna Kiss Me Or Not Thompson Square As She's Walkin Away Zac Brown Band At Last Etta James Bad Moon Rising Dan Fogerty Before He Cheats Carrie Underwood Big Black Horse and a Cherry Tree KT Tunstall Breathe Anna Nalick Breathe Faith Hill Broken Road Rascal Flatts Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Cruisin' Huey Lewis/Gwyneth Paltrow Counting Stars One Republic Dead or Alive Bon Jovi Demons Imagine Dragons Don't You Wanna Stay Jason Aldean/Kelly Clarkson Exes and Ohs Elle King Falling Slowly Glen Hansard and Marketa Irglova February Seven Avett Brothers First Cut is the Deepest Sheryl Crow Forget You CeeLo Green Heartbeat Song Kelly Clarkson Hit Me With Your Best Shot Pat Benetar Home Daughtry Home Phil Phillips Hotel California Eagles I Could Not Ask For More Sara Evans If I Ain't Got You Alicia Keys If I Die Young The Band Perry I'll Be Edwin McCain In My Life Beatles I Will Be Here Steven Curtis Chapman I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor Johnny B. Goode Chuck Berry Just a Girl No Doubt Killing Me Softly Fugees Landslide Fleetwood Mac or Dixie Chicks Let It Go Idina Menzel (Frozen) Living on a Prayer Bon Jovi Locked Out of Heaven Bruno Mars Love is an Open Door Frozen Love Song Sara Bareilles Mambo Italiano Rosemary Clooney Margaritaville Jimmy Buffet Need You Now Lady Antebellum Night and Day Ella Fitzgerald No One Alicia Keys One U2 Our Song Taylor Swift Overkill Colin Haye (Men at Work) Pachebel Canon in D Various Rainbow Connection Sarah McLachlin Redneck Woman Gretchen Wilson Rude Magic Shattered O.A.R. -

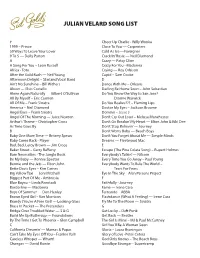

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

Schedule Quickprint TKRN-FM

Schedule QuickPrint TKRN-FM 5/30/2020 7PM through 5/30/2020 11P s: AirTime s: Runtime Schedule: Description 07:00:00p 00:00 Saturday, May 30, 2020 7PM 07:00:00p 03:17 WHO CAN IT BE NOW? / MEN AT WORK 07:03:17p 03:27 YOU MAKE LOVIN' FUN / FLEETWOOD MAC 07:06:44p 03:57 C'MON N' RIDE IT (THE TRAIN) / QUAD CITY DJ'S 07:10:41p 03:05 LOW RIDER / WAR 07:13:46p 03:54 LIVIN' ON A PRAYER / BON JOVI 07:17:40p 02:54 SATURDAY NIGHT / BAY CITY ROLLERS 07:20:34p 03:27 1999 / PRINCE 07:24:01p 04:15 RIDE LIKE THE WIND (ALBUM) / CHRISTOPHER CROSS 07:28:21p 03:30 STOP-SET 07:35:05p 03:49 JUMP / VAN HALEN 07:38:54p 03:55 YOU DROPPED A BOMB ON ME (SINGLE) / GAP BAND 07:42:49p 03:16 COTTON EYE JOE / REDNEX 07:46:05p 02:58 SHAKIN' / EDDIE MONEY 07:49:03p 03:40 ONLY THE GOOD DIE YOUNG / BILLY JOEL 07:52:43p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:00:00p 00:00 Saturday, May 30, 2020 8PM 08:00:00p 03:47 THE LOOK / ROXETTE 08:03:47p 04:45 SATURDAY NIGHT'S ALRIGHT FOR FIGHTING / ELTON JOHN 08:08:32p 04:08 U CAN'T TOUCH THIS / MC HAMMER 08:12:40p 03:38 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME (LIVE) / CHEAP TRICK 08:16:18p 04:03 YOU KEEP ME HANGIN' ON / KIM WILDE 08:20:21p 03:23 LAST DANCE / DONNA SUMMER 08:23:44p 03:19 HUNGRY LIKE THE WOLF / DURAN DURAN 08:27:03p 03:47 FLASHDANCE (WHAT A FEELING) / IRENE CARA 08:30:55p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:37:39p 03:51 DANCING IN THE DARK / BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN 08:41:30p 03:17 LADIES NIGHT / KOOL & THE GANG 08:44:47p 03:10 HANDCLAP / FITZ & THE TANTRUMS 08:47:57p 04:47 I'M YOUR BABY TONIGHT / WHITNEY HOUSTON 08:52:44p 03:30 STOP-SET 09:00:00p 00:00 Saturday, May 30, 2020 9PM 09:00:00p 03:46 THE POWER OF LOVE / HUEY LEWIS & THE NEWS 09:03:46p 04:11 YOU SHOULD BE DANCING / BEE GEES 09:07:57p 03:21 YOU GOTTA FIGHT FOR YOUR RIGHT (TO PARTY) / BEASTIE BOYS 09:11:18p 03:58 S.O.S. -

Genders at Work: Exploring the Role of Workplace Equality in Preventing Men's Violence Against Women

Genders at Work: Exploring the role of workplace equality in preventing men’s violence against women Scott Holmes and Michael Flood Genders at Work: Exploring the role of workplace equality in preventing men’s violence against women 1 White Ribbon is the world’s largest movement of men and boys working to end men’s violence against women and girls, promote gender equity, healthy relationships and a new vision of masculinity. White Ribbon Australia, as part of this global movement, aims to create an Australian society in which all women can live in safety, free from violence and abuse. We are Australia’s only national, male-led violence prevention organisation. We work to examine the root causes of gender-based violence, challenge behaviours and create a cultural shift that leads us to a future without men’s violence against women. Through education, awareness-raising, preventative programs, partnerships and creative campaigns, we are highlighting the positive role men play in preventing men’s violence against women and inspiring them to be part of this social change. The Research and Policy Group provides expert advice, scholarship and general information on furthering prevention efforts in relation to the: • White Ribbon Research Series – Preventing Men’s Violence Against Women • White Ribbon Factsheets Series • Other White Ribbon resources and publications as required. The White Ribbon Policy Research Series is directed by an expert reference group comprising academic, policy and service experts. At least two reports will be published each year and available from the White Ribbon website at www.whiteribbon.org.au Title: Genders at Work: Exploring the role of workplace equality in preventing men’s violence against women. -

Preparation for Government by the Coalition in Opposition 1983–1993 1 Contents

SUMMER SCHOLAR’S PAPER December 2014 ‘In the wilderness’: preparation for government by the Coalition 1 in opposition 1983–1993 Marija Taflaga Parliamentary Library Summer Scholar 2014 Executive summary • This paper examines the Coalition’s policy and preparation efforts to transition into government between 1983 and 1993. • The role of the opposition in the Australian political system is examined and briefly compared with other Westminster countries. The paper also outlines the workings of the shadow Cabinet and the nature of the working relationship between the Liberal Party (LP) and The Nationals (NATS) as a Coalition. • Next, the paper provides a brief historical background of the Coalition’s history in power from 1949 to 1983, and the broader political context in Australia during those years. • Through an examination of key policy documents between 1983 and 1993, the paper argues that different approaches to planning emerged over the decade. First a diagnostic phase from 1983–1984 under the leadership of Andrew Peacock. Second, a policy development phase from 1985–1990 under the leadership of both Peacock and John Howard. The third period from 1990 ̶ 1993 under Dr John Hewson was unique. Hewson’s Opposition engaged in a rigorous and sophisticated regime of policy making and planning never attempted before or since by an Australian opposition. The LP’s attempts to plan for government resulted in the institutionalisation of opposition policy making within the LP and the Coalition. • Each leader’s personal leadership style played an important role in determining the processes underpinning the Coalition’s planning efforts in addition to the overall philosophical approach of the Liberal-led Coalition. -

The Legacy of Robert Menzies in the Liberal Party of Australia

PASSING BY: THE LEGACY OF ROBERT MENZIES IN THE LIBERAL PARTY OF AUSTRALIA A study of John Gorton, Malcolm Fraser and John Howard Sophie Ellen Rose 2012 'A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of BA (Hons) in History, University of Sydney'. 1 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to acknowledge the guidance of my supervisor, Dr. James Curran. Your wisdom and insight into the issues I was considering in my thesis was invaluable. Thank you for your advice and support, not only in my honours’ year but also throughout the course of my degree. Your teaching and clear passion for Australian political history has inspired me to pursue a career in politics. Thank you to Nicholas Eckstein, the 2012 history honours coordinator. Your remarkable empathy, understanding and good advice throughout the year was very much appreciated. I would also like to acknowledge the library staff at the National Library of Australia in Canberra, who enthusiastically and tirelessly assisted me in my collection of sources. Thank you for finding so many boxes for me on such short notice. Thank you to the Aspinall Family for welcoming me into your home and supporting me in the final stages of my thesis and to my housemates, Meg MacCallum and Emma Thompson. Thank you to my family and my friends at church. Thank you also to Daniel Ward for your unwavering support and for bearing with me through the challenging times. Finally, thanks be to God for sustaining me through a year in which I faced many difficulties and for providing me with the support that I needed. -

Songs Always Something There to Remind

Flashback Heart Attack - Songs Always Something There to Remind Me - Naked Eyes Anything Anything – Dramarama Any Way You Want It – Journey Bad Luck - Social Distortion Bizarre Love Triangle - New Order Blister in Sun/Add it Up/Gone Daddy Gone (Medley) - Violent Femmes Blitzkrieg Bop –Ramones Blue Monday - New Order Boys Don’t Cry – The Cure Centerfold - J Giles Band Come on Eileen – Dexies Midnight Runner Dancing w Myself - Billy Idol Destination Unknown – Missing Persons Don’t Change - INXS Don’t Stop Belivin – Journey Don’t You Forget About Me - Simple Minds Don’t You Want Me – Human League Dream Police - Cheap Trick Erotic City - Prince Everybody Wants to Rule the World - Tears for Fears Eyes without a Face – Billy Idol Fascination - Human League Fight for Your Right to Party – Beastie Boys Girls Just Wanna Have Fun – Cyndi Lauper Hungry Like the Wolf – Duran Duran I Love Rock n Roll - Joan Jett I Ran - A Flock of Seagulls In Cars - Gary Newman Jenny Jenny (867-5309) - Tommy Tutone Jesses Girl - Rick Springfield Just Can’t Get Enough - Depeche Mode Just Like Heaven - The Cure Just What I Needed - The Cars Land Down Under – Men at Work Let’s Go Crazy – Prince Live and Let Die – Wings Living on a Prayer – Bon Jovi Mexican Radio – Wall of VooDoo Melt With You - Modern English Metro - Berlin Million Miles Away – The Plimsouls Mirror in the Bathroom – English Beat Modern Love - David Bowie Need You Tonight - INXS Only the Lonely – The Motels Personal Jesus - Depeche Mode Pretty In Pink – Psychedelic Furs Promises Promises – Naked Eyes -

1 Tony Abbott: the Argument for Central Government Santo Santoro

September 2005 Issue 1 www.conservative.com.au Tony Abbott: the argument for central government Santo Santoro: the case for federalism Gerry Wheeler: federalism & VSU 1 contents September 2005 Issue 1 www.conservative.com.au FOCUS ON FEDERALISM 4 Tony Abbott A CONSERVATIVE CASE FOR CENTRALISM 6 Santo Santoro IN DEFENCE OF FEDERALISM 13 Gerry Wheeler VOLUNTARY STUDENT UNIONISM - LESSONS FROM THE STATES THEORY AND PHILOSOPHY 17 Alastair Furnival THE CHALLENGES OF A MODERN CONSERVATISM 21 Mike Pence STATE OF THE CONSERVATIVE MOVEMENT POLICY 25 Nick Minchin PATRON: Senator Hon. Nick Minchin WHY WE SHOULD SELL TELSTRA EDITORIAL COMMITTEE: Senator Santo Santoro (editor) 28 Alexander Downer Alastair Furnival (excutive editor) ON HISTORY AND LIBERTY Senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells Gerry Wheeler David Stevens 33 Michael Brennan PUBLISHER: FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY Conservative Publications Pty Ltd VS SMALLER GOVERNMENT GPO Box 1600 Sydney NSW 2000 38 Concetta Fierravanti-Wells ph: 02 9234 3838 fax: 02 9234 3800 [email protected] IMMIGRATION AND SOCIETY These days it seems that serious consideration of ideas which are mainstream, quintessentially Australian, and in the public interest is often sidelined by the pursuit of more superficial issues. It has become apparent to those associated with this enterprise that there is a need for a journal - namely the conservative - to unashamedly raise issues which are increasingly prominent in the political, economic and social consciousness of our country’s activists: and to do so through the prism of progressive Liberal thought. In this inaugural issue of the conservative there is focus on the growing debate about federalism - an issue which touches the very core and foundations of our system of government. -

In the Company of Men: Male Dominance and Sexual Harassment

IN THE COMPANY OF MEN The Northeastern Series on Gender, Crime, and Law edited by Claire Renzetti, St. Joseph’s University Battered Women in the Courtroom: The Power of Judicial Responses James Ptacek Divided Passions: Public Opinions on Abortion and the Death Penalty Kimberly J. Cook Emotional Trials: The Moral Dilemmas of Women Criminal Defense Attorneys Cynthia Siemsen Gender and Community Policing: Walking the Talk Susan L. Miller Harsh Punishment: International Experiences of Women’s Imprisonment edited by Sandy Cook and Susanne Davies Listening to Olivia: Violence, Poverty, and Prostitution Jody Raphael No Safe Haven: Stories of Women in Prison Lori B. Girshick Saving Bernice: Battered Women, Welfare, and Poverty Jody Raphael Understanding Domestic Homicide Neil Websdale Woman-to-Woman Sexual Violence: Does She Call It Rape? Lori B. Girshick IN THE COMPANY OF MEN Male Dominance and Sexual Harassment Edited by James E. Gruber and Phoebe Morgan Northeastern University Press Northeastern University Press Copyright by James E. Gruber and Phoebe Morgan All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data In the company of men : male dominance and sexual harassment / edited by James E. Gruber and Phoebe Morgan. p. cm. — (The Northeastern series on gender, crime, and law) --- (cl : alk. paper)— --- (pa : alk. paper) . -

Menzies and Howard on Themselves: Liberal Memoir, Memory and Myth Making

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2018 Menzies and Howard on themselves: Liberal memoir, memory and myth making Zachary Gorman University of Wollongong, [email protected] Gregory C. Melleuish University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gorman, Zachary and Melleuish, Gregory C., "Menzies and Howard on themselves: Liberal memoir, memory and myth making" (2018). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 3442. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/3442 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Menzies and Howard on themselves: Liberal memoir, memory and myth making Abstract This article compares the memoirs of Sir Robert Menzies and John Howard, as well as Howard's book on Menzies, examining what these works by the two most successful Liberal prime ministers indicate about the evolution of the Liberal Party's liberalism. Howard's memoirs are far more 'political', candid and ideologically engaged than those of Menzies. Howard acknowledges that politics is about political power and winning it, while Menzies was more concerned with the political leader as statesman. Howard's works can be viewed as a continuation of the 'history wars'. He wishes to create a Liberal tradition to match that of the Labor Party. Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Gorman, Z.