Translating Drama: an Interpretation, an Investigation G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dakkali & Pabbada Cultural Art in Madras Presidency & Hyderabad

www.ijcrt.org © 2017 IJCRT | Volume 5, Issue 4 December 2017 | ISSN: 2320-2882 Dakkali & Pabbada Cultural Art in Madras Presidency & Hyderabad State. Dr. Jayaram Gollapudi Assistant Professor and Post-Doctoral Fellow Osmania University The title shows unique name in the society the class is based untouchable, mainly in this depressed class are Mang and Mahar . Mang commu nity is Madiga , Chamar, Chindu and Mastini etc; in the Mahar community Mala, Mala Dasari, Netakani and pambala etc; but mainly Madiga Leather worker community is main role in the depressed class culture Art in Madrass presidency and Nizam’s Hyderabad State. As on cultural art area important dependent castes are Dakkali and Pabbada. The Dibbida copper plate inscription of Mastya Arjuna, dated S.119l (A.D. 1269) refers to a tank intended for the use of Antyas (Antyajataka) while delineating the boundaries of the gifted village. This clearly suggests that those who belonged to the lower status of society were not allowed to use the common tanks of the village and that separate tanks were excavated for their use. Chandalas were often expected to render service without any special remuneration, a practice which is known as Vetti (free labour). However, some land was allotted for their subsistence as evident from the term Chandala Kshetramu mentioned in the Chevuru plates of Eastern Chalukya Amma. The research methodology for this project is needed to be explained from important basic points. To understand the Culture is it is necessary to understand the long-term trends in the agrarian economy and the famine sufferings through the historical methodology. -

PROFILE of Dr. UMMIDI SANTHI DEPARTMENT of TELUGU

PROFILE OF Dr. UMMIDI SANTHI DEPARTMENT OF TELUGU Dr. U. Santhi Assistant Professor Department of Telugu, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University, Etcherla, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, India-532 410. I. PERSONAL INFORMATION: Date of Birth : 18-08-1972 Academic Qualifications : M.A. Telugu Ph.D. A.P.CET-H.T.No.152309163, Dt: 15-02-2015. Other Qualifications : M.Com, Law, NCC “C” Martial Arts Advanced Pink Belt DCA Technical Qualifications : Type Writing English Higher Grade Type Writing Telugu Higher Grade Tally 9.0 Page 1 of 10 Specializations : Journalism Janapadha Vignanam Dhalitha Vadhamu Teaching Experience : 8 years of Lecturer experience in Junior College 3 years of Lecturer experience in Telugu up to Degree Level 3 years of Administrator experience in Corporate Colleges 8 years of Experience as Assistant Professor in Telugu, Department of Telugu, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University, Etcherla, Srikakulam II. Address for Communication : Dr. U. SANTHI D/o U. Krishna Rao (Late) Door No.2-11-7, MVP Colony, Beside Appughar, Visakhapatnam-530017, Cell: 9849018512, Email: [email protected] Core papers in Telugu at Post Graduate Level Specialization papers at P.G. Level. Folk Literature Journalism Dalith Sahithyam Ancient Literature of Telugu Modern Literature Veman Feminism III. Published Research Papers: Papers Published in National/International Journals: 1) October, 2013 - ISSN – 2322 – 2481, Page 40, Prakashini Magzene Topic; Literature role in Independence. 2) March,2014 - ISSN – 2322 – 0481, page No.58-59, Prakashini Topic; Child Literature Joshva Poetry. 3) October, 2014 - ISSN – 2322 – 2481, Page 26, 27, 28 article No.26, Topic : Prakashini Magzene, Topic :Gurajada Apparao –(women stories). -

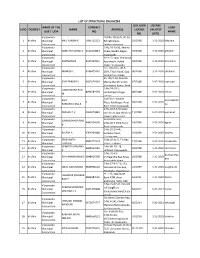

Structural Engineers List

LIST OF STRUCTURAL ENGINEERS ULB /UDA LICENSE NAME OF THE CONTACT USER S.NO DISTRICT NAME ADDRESS LICENSE VALIDITY ULB / UDA NO NAME NO. UPTO Vijayawada Flat No.105 (GF), Sri Sai 1 Krishna Municipal ANIL KUMAR K 7095712323 RatnaEnclave, 01/2008 3-31-2020 kakumar Corporation Seetharampuram Vijayawada D.No.26-20-30, Swamy 2 Krishna Municipal RAMESH KUMAR G 9440140843 Street,Gandhi Nagar. 03/2008 3-31-2020 grkumar Corporation Vijayawada Vijayawada 60-3-17, Opp: Chaitanya 3 Krishna Municipal RAVINDRA N 9440709915 Apartment, Ashok 04/2008 3-31-2020 nravindra Corporation Nagar, Vijayawada Vijayawada C/o. Desicons, 40-5- 4 Krishna Municipal MAHESH C 9246475767 19/9, Tikkle Road, Opp 06/2008 3-31-2020 cmahesh Corporation Siddhartha college, Vijayawada 43-106/1-58, Bharath 5 Krishna Municipal SIVA PRASAD S 9951074339 Matha Mandir Street, 07/2008 3-31-2020 ssprasad Corporation Nandamuri Nagar, Ajith Vijayawada D.No.74-10-1, LINGESWARA RAO 6 Krishna Municipal 8096281594 LakshmipathiNagar 08/2008 3-31-2020 mlrao M Corporation Colony, Vijayawada 2nd Floor, Kakarla SIVA asramakrish 7 Krishna Municipal 0 Plaza, KalaNagar, Near 09/2008 3-31-2020 RAMAKRISHNA A na Corporation Benz Circle,Vijayawada Vijayawada D.No.28-5-1/3,kuppa 8 Krishna Municipal PRASAD P.V 9966573883 vari street,opp.Hotel raj 11/2008 3-31-2020 pvprasad Corporation towers ,eluru road Vijayawada Sri Sai Planners, GANGADHARA RAO 9 Krishna Municipal 9440109695 D.No.40-5-19/4,Tickle 14/2008 3-31-2020 bgrao B Corporation Road, Vijayawada Vijayawada D.No.29-19-44, 10 Krishna Municipal RAJESH A 9703369888 Dornakal Road, 16/2008 3-31-2020 arajesh Corporation Suryaraopet, Vijayawada SREEKANTH D.No.39-11-5, T.K.Rao 11 Krishna 9885721574 17/2008 3-31-2020 lsreekanth Municipal LINGALA Street,Labbipet, Vijayawada VENKATA RAMANA D.No.40-1/1-18, 12 Krishna 9848111681 18/2008 3-31-2020 svramana Municipal S. -

The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC

The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC Name of the Institution : ANDHRA LOYOLA COLLEGE (Autonomous), Ring Road, Vijayawada – 520 008 Krishna Dt. Andhra Pradesh Year of Report: 2011-2012 Part A: The plan of action chalked out by the IQAC in the beginning of the year towards quality enhancement and the outcome achieved by the end of the year. 1. Conduct of faculty development programmes 2. Introduction of more vocational add on programmes 3. Impetus to be given to active participation of students in various co-curricular activities 4. Augmentation of Library services. 5. Impetus to Research and consultancy services Part B: 1. Activities reflecting the goals and objectives of the institution: The primary objective of the College is to provide higher education in a Christian atmosphere of all-round excellence to all deserving students, especially those belonging to the Catholic Christian Community along with other students, irrespective of their caste and creed. The college strives to achieve the Jesuit educational goal of "forming men and women for others with competence, conscience and compassionate commitment.” i) In order to achieve the set objectives and goals, the College follows a multi- dimensional approach. 1. Fundamentals of Computer are taught to all the first year students. 2. All the first year students put in 60 hours of social work. 3. The third year students undertake group research projects. 4. Students are sent to other academic institutions and industries for internship programmes. 5. Placement training is offered for all the Undergraduate students. 6. Full-fledged audio and video studio has been established to offer skill training for the visual communication students. -

Andhra Loyola College (Autonomous), Vijayawada-8

ANDHRA LOYOLA COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), VIJAYAWADA-8 Accredited at A Grade with a CGPA of 3.65/4.00 in II Cycle by NAAC The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) (July 1, 2015 to June 30, 2016) Track ID- APCOGN10174 Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) Bangalore Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) December, 2016 Andhra Loyola College (Autonomous), Vijayawada-8 The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC (July 1, 2015 to June 30, 2016) Contents Page No. Part – A 1. Details of the Institution 01 2. IQAC Composition and Activities 03 Part – B Criterion – I: Curricular Aspects 05 Criterion – II: Teaching, Learning and Evaluation 06 Criterion – III: Research, Consultancy and Extension 08 Criterion – IV: Infrastructure and Learning Resources 12 Criterion – V: Student Support and Progression 14 Criterion – VI: Governance, Leadership and Management 17 Criterion – VII: Innovations and Best Practices 22 Plans of institution for next year 24 Annexure I: Abbreviations Annexure II: Plan of Action 2015-2016 Annexure III: Annual Academic Report 2015-16 Andhra Loyola College (Autonomous), Vijayawada-8 The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC (July 1, 2015 to June 30, 2016) Part – A 1. Details of the Institution 1.1 Name of the Institution : Andhra Loyola College (Autonomous) 1.2 Address Line 1 : Door No. 16-14-15 Address Line 2 : Govt. Polytechnic Post City/Town : Vijayawada State : Andhra Pradesh Pin Code : 520 008 Institution e-mail address : [email protected] Contact Nos. : 0866-2476082 : Fr.Dr.G.A.P. Kishore, SJ Name of the Head of the institution Principal Tel. No. -

UGC MHRD E Pathshala

UGC MHRD e Pathshala Subject: English Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Paper 09: Comparative Literature: Drama in India Paper Coordinator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Module 12: Gurjada Appa Rao: Kanyasulkam Content Writer: Dr. Vamshi Krishna Reddy, NIT Rourkela Content Reviewer: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Language Editor: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Introduction: Telugu Theatre has a prominent place in producing several pioneering works which have been translated into English and many other Indian languages. Among them, Kanyasulkam by Gurazada Venkata Appa Rao (1862-1915) is considered as the greatest. Appa Rao is known as a pathfinder of modernism in Telugu Literature. Most of the time in his life, he was with Vijayanagaram rulers by working and producing lot of research in English classics. He produced his writings by using the form of common men Telugu language. One of his masterpieces, a prose plays ' Kanyasulkam1', inscribed in the north costal Andhra dialect, which is a popular work of art in the genre of Telugu Drama and remains as one of the most admiring literary works. Appa Rao’s 'Mutyala Saraalu (Strings of Pearls) and 'Neelagiri Paainlu (Songs of Neelagiri) place a new trend in Telugu poetry. Career and Works of the author: Gurajada Venkata Appa Rao, popularly known as Gurajada, born on Septrmber 21st , 1862 in Rayavaram Village, near Yalamanchili of Visakapattanam district of Andhra Pradesh into a Telugu Brahmin family. Some of his popular works along with Kanyasulkam are Prathaparudreeyam, Purnamma and Viswavidyalayalu. He was honored with titles like Kavishekara and Abhyudaya Kavita Pithamahudu. -

16 | SCIENCES LANDSCAPE" on Nov., 23-34, 2018 Organised by Social Sciences Departments, St.Joseph's College for Women ( a ), Visakhapatnam

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BUSINESS, MANAGEMENT AND ALLIED SCIENCES (IJBMAS) A Peer Reviewed International Research Journal www.ijbmas.in ISSN: 2349-4638 Vol.5. Issue.S2.2018 (Nov) A RICH CULTURAL HERITAGE HUB – A STUDY ON VIZIANAGARAM DISTRICT Dr. P.Jayalakshmi Reader in Economics, St.Joseph’s College for Women (A), Visakhapatnam-4, [email protected] Dr.Ch. Annapurna Reader in Telugu, St. Joseph’s College for Women (A), Visakhapatnam-4 Abstract Indian Culture and heritage played a great role in the World. Among 29 States Andhra Pradesh is a considered as rich cul- tural heritage hub. The cultural heritage attracts the tourists. Andhra Pradesh Tourism was developed at a higher rate and tourist visitor’s number increasing rapidly. Tourism is a potent tool to economic development of the state. The debate sur- rounding the role of tourism in the retrievals of history has gained much importance recently. Several scholars have argued that cultural heritage tourism plays an important role in discovering identity of the kingdoms ruling at different periods. The district of Vizianagaram was ruled by the Maharaja’s of Gajapathi’s families. The Vizianagaram district was a rich cultural hub in coastal Andhra. The King’s of Vizianagaram was developed highly cultural heritage and tourist places. Thus, cultural heritage tourism is found to be high potential source with which dominant narratives of history, culture and identity are always reckoned. The promotion of cultural heritage tourism was increasing in the district. In this paper, the author attempt to study the cultural heritage development in vizianagaram district was analyzed in various ways. -

The Artifice of Brahmin Masculinity in South Indian Dance

Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Ahmanson Foundation Endowment Fund in Humanities. Impersonations Impersonations The Artifice of Brahmin Masculinity in South Indian Dance Harshita Mruthinti Kamath UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advanc- ing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2019 by Harshita Mruthinti Kamath This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. Suggested citation: Kamath, H. M. Impersonations: The Artifice of Brahmin Masculinity in South Indian Dance. Oakland: University of California Press, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.72 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kamath, Harshita Mruthinti, 1982- author. Title: Impersonations : the artifice of Brahmin masculinity in South Indian dance / Harshita Mruthinti Kamath. Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Government of India Ministry of Tourism Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No.1072 Answered on 08.02.2021 Projects Under Adopt a Herit

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF TOURISM LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.1072 ANSWERED ON 08.02.2021 PROJECTS UNDER ADOPT A HERITAGE SCHEME 1072. DR. SANJEEV KUMAR SINGARI: Will the Minister of TOURISM be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government has sanctioned any projects under “Adopt a Heritage Scheme” to the State of Andhra Pradesh; (b) if so, the details thereof and the rules governing the sanction of the scheme; and (c) the list of Government recognised heritage sites in the State of Andhra Pradesh? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE FOR TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) (SHRI PRAHLAD SINGH PATEL) (a) and (b): The Ministry of Tourism, Government of India has launched the “Adopt a Heritage: Apni Dharohar, Apni Pehchaan” project which is a collaborative effort by the Ministry of Tourism, Ministry of Culture, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and State Governments/ Union Territory Administrations for developing tourism amenities at heritage/ natural/ tourist sites spread across India for making them tourist friendly, in a planned and phased manner. The project aims to encourage companies from public sector, private sector, trusts, NGOs, individuals and other stakeholders to become ‘Monument Mitras’ and take up the responsibility of developing and upgrading the basic and advanced tourist amenities at these sites as per their interest and viability in terms of a sustainable investment model under CSR. They would also look after the Operation & Maintenance of the same. Under the project, 27 Memorandum of Understanding (MoUs) have been awarded to 13 Monument Mitras for twenty-five (25) sites and two (2) Technological interventions across India as per list enclosed at Annexure- I. -

Transformation of Mythological Characters: Observation in North Coastal Andhra Folk Performance Shiva Bhagavatham

Transformation of mythological characters: Observation in North Coastal Andhra Folk Performance Shiva Bhagavatham Dissertation submitted to Centre for Cultural Resources and Training in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of junior fellowship to outstanding persons in the Field of culture (theatre) GOVINDA RAO SIVVALA (File No. CCRT/JF-3/62/2015 (2013-2014)) CENTRE FOR CULTURAL RESOURCE AND TRAINING CENTRE (CCRT), (UNDER THE AEGIS OF MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVT. OF INDIA) 15-A, SECTOR-7, DWARKA, NEW DELHI- 110075 Declaration I declare that this dissertation titled “Transformation of mythological characters: Observation in North Coastal Andhra Folk Performance Shiva Bhagavatham submitted by me at the Centre for Cultural Resources and training, Under the aegis of Ministry of Culture, Govt. India, for the award of Junior Fellowship for 2013-2014 in the field of Theatre, sub-filed theatre, File No. CCRT/JF-3/62/2015 to outstanding Persons in the field of Culture, is an original work and has not been submitted by me so far, in part or full for any other degree or diploma of this or any other university or institution. Govinda Rao Sivvala Contents Page No. Acknowledgement i Chapter 1 Introduction 1- 10 Chapter 2 Textual analysis of the Performance: Shiva Bhagavatham 11 - 26 Chapter 3 Shiva Bhagavatham in performance 27 - 42 Chapter 4 Tracing the social milieu in mythological performance: Shiva Bhagavatham 43 - 54 Bibliography 55 Acknowledgement After completing this dissertation I would like to be grateful to the Centre for Cultural Resources and training, Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India for granting me Junior Research Fellowship, in theatre field. -

CHAPTER Hi LIFE SKETCH of GURAZADA

CHAPTER Hi LIFE SKETCH OF GURAZADA 102 LIFE SKETCH OF GURAZADA In this chapter, an attempt is made to present a brief history of Gurazada's life and its background, which serves the necessar>' prelude for his biographical sketch. Later a vivid description of his life will be presented. Gurazada's forefather, Akkiraju left his native village Jampani in Guntur district and migrated to Gurazada village in Krishna district in search of livelihood and settled down there in the later half of the seventeenth century. In course of time they adopted the name of the village for their family name ' Akkiraju built two temples in the village. The family is a Niyogi family of Kaundinya gotram.^ Akkiraju had three sons - Surapuraju, Peda Veerraju and China Veerraju. Among them Surapuraju held the post of Diwan of Nuzvid Zamindars and acquired landed property from the Kamadan Samasthanam." Pedda Veerraju had seven sons. His fourth son Pattabhiramayya left Gurazada in search of livelihood and settled at Masulipatam. He worked under Srinadhuni Kodandaramayya, who was a Dubasi (interpreter) in the French East India Company and was also running shipping business. Kodandaramayya was impressed by the integrity and intelligence of Pattabiramayya and gave him his daughter in marriage. Though both families were Brahmins, they belonged to different sub-sects and marriage between different sects then was forbidden. But they had the courage to defy the custom and arranged the marriage. Thus it can be concluded that seeds of social reform was in the family history itself 103 Pattabhiramayya was the father of Gurazada's grand father. -

Annual Report 2018–2019

Annual Report 2018–2019 Sahitya Akademi (National Academy of Letters) President : Dr Chandrashekhar Kambar Vice-President : Sri Madhav Kaushik Secretary : Dr K. Sreenivasarao ............................................CONTENTS Sahitya Akademi 5 Projects and Schemes 8 Highlights of 2018–2019 12 Awards 13 – Sahitya Akademi Award 2018 15 – Sahitya Akademi Prize For Translation 2018 19 – Yuva Puraskar 2018 23 – Bal Sahitya Puraskar 2018 27 Programmes 31 – Sahitya Akademi Awards 2018 Presentation Ceremony 32 – Sahitya Akademi Prize For Translation 2017 Presentation Ceremony 55 – Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar 2018 Presentation Ceremony 58 – Bal Sahitya Puraskar 2018 Presentation Ceremony 63 – Seminars, Symposia, Writers’ Meets, etc. 68 List of Programmes organized by Sahitya Akademi in 2018–2019 152 Governing Body, Regional Board Meetings and Language Advisory Boards held in 2018–2019 180 Book Exhibitions / Book Fairs 183 Books Published 191 Annual Accounts 231 SAHITYA AKADEMI (National Academy of Letters) Sahitya Akademi, India’s premier Institution levels, more than 100 Symposia and a large of Letters, preserves and promotes literature number of birth centenary seminars and in 24 languages of India recognized by it. It symposia, in addition to more than 400 literary organizes programmes, confers Awards and gatherings, workshops and lectures. Meet the Fellowships on writers in Indian languages, Author (where a distinguished writer talks about and publishes books throughout the year and his / her works and life), Samvatsar Lectures in 24 recognized