Chapter-5-Meet-The-Living-Primates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JVP 26(3) September 2006—ABSTRACTS

Neoceti Symposium, Saturday 8:45 acid-prepared osteolepiforms Medoevia and Gogonasus has offered strong support for BODY SIZE AND CRYPTIC TROPHIC SEPARATION OF GENERALIZED Jarvik’s interpretation, but Eusthenopteron itself has not been reexamined in detail. PIERCE-FEEDING CETACEANS: THE ROLE OF FEEDING DIVERSITY DUR- Uncertainty has persisted about the relationship between the large endoskeletal “fenestra ING THE RISE OF THE NEOCETI endochoanalis” and the apparently much smaller choana, and about the occlusion of upper ADAM, Peter, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; JETT, Kristin, Univ. of and lower jaw fangs relative to the choana. California, Davis, Davis, CA; OLSON, Joshua, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los A CT scan investigation of a large skull of Eusthenopteron, carried out in collaboration Angeles, CA with University of Texas and Parc de Miguasha, offers an opportunity to image and digital- Marine mammals with homodont dentition and relatively little specialization of the feeding ly “dissect” a complete three-dimensional snout region. We find that a choana is indeed apparatus are often categorized as generalist eaters of squid and fish. However, analyses of present, somewhat narrower but otherwise similar to that described by Jarvik. It does not many modern ecosystems reveal the importance of body size in determining trophic parti- receive the anterior coronoid fang, which bites mesial to the edge of the dermopalatine and tioning and diversity among predators. We established relationships between body sizes of is received by a pit in that bone. The fenestra endochoanalis is partly floored by the vomer extant cetaceans and their prey in order to infer prey size and potential trophic separation of and the dermopalatine, restricting the choana to the lateral part of the fenestra. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

LIS T OF ILL US TRA TIONS. IX Pa«e. Apices of ovipositors : o, Polysphincta texaiui Cresson ; &, Eymenoepi- meois iciltii (Cresson); Mandible; c, H. tmltii (Cresson) 389 Apex of ovipositor of Theronia fulvesceiis Cresson 389 Apices of ovipositors: a, Itoplectis canqMisitor Say; b, Apechthis pictir cornis (Cresson) 389 Apex of abdomen of female of Coleocentrus occidentalis 390 Areolet of Lahena grallatoi- (Say) 390 Areolets: a, Tromatohia rufovariata (Cresson) ; b, Itoplectis conquisitor (Say) ; c, Epiurus alboricta (Cresson) 390 Sessile first tergite of Perithous pleuralis (Cresson) 390 Petioatel first tergite of Xorides yukonensis (Rohwer) 390 Mandible of Poemenva americana (Cresson) 391 Female of Labena confusa Rohwer 412 Female of Rhyssella nitida (Cresson) 424 Propodeum of Zonde* picea*u« (Rohwer) 434 Front view of head of Xoi'ides albopictus (Cresson) 437 Propodeum and basal abdominal segments of Xorides albopictus (Cresson) 437 Apical abdomen segments of Xorides albopictus (Cresson) 437 Female of Xorides rileyi (Ashmead) 440 Front view of head of Deuteroxorides caryae (Harrington) 446 Propodeum and basal abdominal segments of Deuteroxorides caryae (Harrington) 446 Apical abdominal segments of Z)c«feroa:ori<Ze« caryae (Harrington) 446 Female of Deuteroxorides caryae (Harrington) 447 Female of Odontomerus canadensis Provancher 459 Female of Phytodietus annulatus (Provancher) 467 Femaie of Phydotietus annulatus (Provancher) 467 Diagram showing relation of dike to vein, Hecla Mine. A, Dike; B, Crushed material with quartz and ore; C, Galena; D, Quartzite wall rock ; width of section 15 feet 481 Showing relation to dikes (A) to vein (B) on No. 1 level of Marsh Mine_ 484 Showing relation of dike (A) to vein (B) on 2,000-foot level of Standard- Mammoth Mine 492 Showing relation of dike (A) to vein (B) on 1,200-foot level of Standard- Mammoth Mine 492 Coleocentrus occidentalis. -

Monkeys, Apes and Human Identity in the Early American Republic Brett Mizelle University Ofminnesota

"Man Cannot Behold It Without Contemplating Himself": Monkeys, Apes and Human Identity in the Early American Republic Brett Mizelle University ofMinnesota While seeking refuge in Germantown from the yellow fever epidemic that plagued Philadelphia in the summer of 1793, Elizabeth Drinker and her friends encountered a man traveling through the town "with something in a barrel to Show which he said was half man, half beast." Although Drinker wrote that the proprietor of this animal exhibition "call'd it a Man[de]," she "believe[d] it was a young Baboon." Intrigued by the possibility of observing first hand a creature that supposedly blurred the boundary between the human and the animal, Drinker and her party "paid 5 l/2 [pence] for seeing it." After examin- ing this creature, however, Drinker noted that she was disturbed by this exhi- bition, concluding that the baboon "look'd sorrowful, I pity'd the poor thing, and wished it in its own Country."' The exhibitor's marketing of this exotic animal as "half man, half beast" and Drinker's positive feelings for this captive creature both depended upon an imagined resemblance between this baboon and human beings. While the proprietor exaggerated and manipulated this resemblance to sell his animal as a hybrid, threshold creature, Drinker similarly drew upon resemblance when she felt sorry for "the poor thing." The idea of resemblance seen here in both the exploitation of and sympathy for this baboon emerges, Thierry Lenain argues, because "a series of common features-general physical appearance, plus some striking details of the appearance and some behavioral features- immediately link monkeys with men in the imagination." These analogies are exaggerated and multiplied as Numerous human characteristics are displayed in the monkey's physiognomy and movements, eliciting a reaction of the 'it almost looks' type, and the onlooker spontaneously seeks signals that endorse this reaction, ignoring characteristics and features that are peculiar to the animal alone. -

The Survival of the Central American Squirrel Monkey

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2005 The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Burghardt, Liana, "The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context" (2005). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 435. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/435 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Survival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt Carleton College Fall 2005 Burghardt 2 I dedicate this paper which documents my first scientific adventure in the field to my father. “It is often necessary to put aside the objective measurements favored in controlled laboratory environments and to adopt a more subjective naturalistic viewpoint in order to see pattern and consistency in the rich, varied context of the natural environment” (Baldwin and Baldwin 1971: 48). Acknowledgments This paper has truly been an adventure and as is common I have many people I wish to thank. -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Chimpanzee

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 25 May 2017 SPECIES Original: English 12th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Manila, Philippines, 23 - 28 October 2017 Agenda Item 25.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDIX I AND II OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Governments of Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania have jointly submitted the attached proposal* for the inclusion of the Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) on Appendix I and II of CMS. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDICES I AND II OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A: PROPOSAL Inclusion of Pan troglodytes in Appendix I and II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. B: PROPONENTS: Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania C: SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Mammalia 1.2 Order: Primates 1.3 Family: Hominidae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach 1775) (Wilson & Reeder 2005) [Note: Pan troglodytes is understood in the sense of Wilson and Reeder (2005), the current reference for terrestrial mammals used by CMS). -

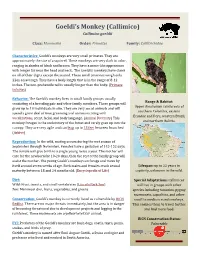

Goeldi's Monkey

Goeldi’s Monkey (Callimico) Callimico goeldii Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Family: Callitrichidae Characteristics: Goeldi’s monkeys are very small primates. They are approximately the size of a squirrel. These monkeys are very dark in color, ranging in shades of black and brown. They have a mane-like appearance with longer fur near the head and neck. The Goeldi’s monkeys have claws on all of their digits except the second. These small primates weigh only 22oz on average. They have a body length that is in the range of 8-12 inches. The non-prehensile tail is usually longer than the body. (Primate Info Net) Behavior: The Goeldi’s monkey lives in small family groups usually consisting of a breeding pair and other family members. These groups will Range & Habitat: Upper Amazonian rainforests of grow up to 10 individuals in size. They are very social animals and will southern Colombia, eastern spend a great deal of time grooming and communicating with Ecuador and Peru, western Brazil, vocalizations, scent, facial, and body language. (Animal Diversity) This and northern Bolivia. monkey forages in the understory of the forest and rarely goes up into the canopy. They are very agile and can leap up to 13 feet between branches! (Arkive) Reproduction: In the wild, mating occurs during the wet season of September through November. Females have a gestation of 145-152 days. The female will give birth to a single young twice a year. The mother will care for the newborn for 10-20 days, then the rest of the family group will assist the mother. -

Notes on Lagothrix Flavicauda (Primates: Atelidae): Oldest Known Specimen and the Importance of the Revisions of Museum Specimens

ZOOLOGIA 36: e29951 ISSN 1984-4689 (online) zoologia.pensoft.net SHORT COMMUNICATION Notes on Lagothrix flavicauda (Primates: Atelidae): oldest known specimen and the importance of the revisions of museum specimens José Eduardo Serrano-Villavicencio 1,2, Luís Fábio Silveira 3 1Programa de Pós-graduação em Mastozoologia, Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo. Avenida Nazaré 481, Ipiranga, 04263-000 São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 2Centro de Investigación Biodiversidad Sostenible (BioS), Lima, Peru. 3Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo. Avenida Nazaré 481, Ipiranga, 04263-000 São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Corresponding author: José Eduardo Serrano-Villavicencio ([email protected]) http://zoobank.org/B29AF1E9-F78A-475D-AF1F-3AECEBABA626 ABSTRACT. The yellow-tailed woolly monkey, Lagothrix flavicauda (Humboldt, 1812), is a large atelid endemic to the cloud forests of Peru. The identity of this species was uncertain for at least 150 years, since its original description in 1812 without a voucher specimen. Additionally, the absence of expeditions to the remote Peruvian cloud forests made it impossible to collect material that would help to confirm the true identity ofL. flavicauda during the 19th and first half of the 20th century. Until now, the specimens of L. flavicauda collected by H. Watkins, in 1925, in La Lejía (Amazonas, Peru) were thought to be the oldest ones deposited in any scientific collection. Nevertheless, after reviewing the databases of the several international museums and literature, we found one specimen of L. flavicauda deposited at the Muséum National d’histoire Naturelle (Paris, France) collected in 1900 by G.A. Baër, in the most eastern part of San Martín (Peru), where the presence of this species was not confirmed until 2011. -

8. Primate Evolution

8. Primate Evolution Jonathan M. G. Perry, Ph.D., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Stephanie L. Canington, B.A., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Learning Objectives • Understand the major trends in primate evolution from the origin of primates to the origin of our own species • Learn about primate adaptations and how they characterize major primate groups • Discuss the kinds of evidence that anthropologists use to find out how extinct primates are related to each other and to living primates • Recognize how the changing geography and climate of Earth have influenced where and when primates have thrived or gone extinct The first fifty million years of primate evolution was a series of adaptive radiations leading to the diversification of the earliest lemurs, monkeys, and apes. The primate story begins in the canopy and understory of conifer-dominated forests, with our small, furtive ancestors subsisting at night, beneath the notice of day-active dinosaurs. From the archaic plesiadapiforms (archaic primates) to the earliest groups of true primates (euprimates), the origin of our own order is characterized by the struggle for new food sources and microhabitats in the arboreal setting. Climate change forced major extinctions as the northern continents became increasingly dry, cold, and seasonal and as tropical rainforests gave way to deciduous forests, woodlands, and eventually grasslands. Lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers—once diverse groups containing many species—became rare, except for lemurs in Madagascar where there were no anthropoid competitors and perhaps few predators. Meanwhile, anthropoids (monkeys and apes) emerged in the Old World, then dispersed across parts of the northern hemisphere, Africa, and ultimately South America. -

The Night Monkey, Aotes Triuirgatus (Cebidae, Platyrrhini, Anthropoidea)

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Volume 165, number 1 FEBS 1071 January 1984 The myoglobin of primates: the Night Monkey, Aotes triuirgatus (Cebidae, Platyrrhini, Anthropoidea) Nils Heinbokel and Hermann Lehmann Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, Tennis Court Road, Cambridge CB2 IQW, England Received 26 October 1983 The amino acid sequence of the myoglobin of the South American Night Monkey, Aotes trivirgatus, is identical to that of the marmoset (Callithrix jacchus [l]) except for residue 21 which is isoleucine in the marmoset, like in all other anthropoids, but valine in Aotes. Analysis of a possible pathway of the evolution of Aotes myoglobin using 18 known primate myoglobin sequences [2-51 supports the classification of the Night Monkey within Anthropoidea and Platyrrhini but it indicates that this species might be more closely related to the marmoset (family Callitrichidae) than to the family Cebidae as a member of which it is commonly classified. Aotes trivirgatus Myoglobin Sequential analysis Amino acid analysis High-performance liquid chromatography of peptides Molecular evolution 1. INTRODUCTION phylogeny of the Night Monkey based on im- munological comparisons of serum proteins [8,9] The small, purely arboreal South American and on &type haemoglobin chain sequences [lo] Night Monkey, Aotes trivirgatus, is the only noc- has not been conclusive. We determined the amino turnal species in the primate suborder An- acid sequence of the myoglobin of the Night thropoidea. Two thirds of the Prosimii, the other Monkey in order to reconstruct a possible pathway primate suborder, are exclusively nocturnal. This of the evolution of this protein using 18 known resemblance and other similarities of physical and primate myoglobin sequences aiming to obtain behavioural characteristics of Aotes and Prosimii some insights into the phylogenetic relationships of have mostly been considered as convergent adapta- this primate. -

Capuchins Are the Most Intelligent New World Monkeys – Perhaps As Intelligent As Chimpanzees

Hooded Capuchin Cebus paella cay Capuchin IQ - Capuchins are the most intelligent New World monkeys – perhaps as intelligent as chimpanzees. They are noted for their ability to fashion and use tools. Because of their ability to learn and remember, they were once trained as “organ grinder” monkeys, are often used in movies and have even been trained to assist disabled people with routine tasks around the house. Get a Grip - Hooded capuchins have a semi-prehensile tail that they can use to grip objects. They have opposable thumbs and big toes on their hands and feet further enabling them to easily manipulate objects. They use their prehensile tail to anchor themselves when climbing around in the trees and to keep them from falling when they sleep. Unlike some monkeys with prehensile tails, capuchins cannot hang by their tail alone. Classification The hooded capuchin is also been referred to as the tufted or brown capuchin. Class: Mammalia Order: Primate Family: Cebidae Genus: Cebus Species: paella Subspecies: cay Distribution This species ranges through northern South America, specifically Venezuela, Brazil, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana. Habitat Canopies of tropical and mountain rainforests. Physical Description • Hooded capuchins are 12-22 inches (30-56 cm) long with a 15-22 inch (38-56 cm) tail. • Adults weigh six to eight pounds (3-4 kg). • Their fur is light to dark brown with a distinctive black cap on the head. • They have semi-prehensile tails. • Hooded capuchins have tufts of hair that form ridges along the side of the top of their head. Diet What Does It Eat? In the wild: Fruit, flowers, leaves, insects, birds, eggs, lizards, and small mammals. -

Fossil Primates

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 16 www.accessscience.com Fossil primates Contributed by: Eric Delson Publication year: 2014 Extinct members of the order of mammals to which humans belong. All current classifications divide the living primates into two major groups (suborders): the Strepsirhini or “lower” primates (lemurs, lorises, and bushbabies) and the Haplorhini or “higher” primates [tarsiers and anthropoids (New and Old World monkeys, greater and lesser apes, and humans)]. Some fossil groups (omomyiforms and adapiforms) can be placed with or near these two extant groupings; however, there is contention whether the Plesiadapiformes represent the earliest relatives of primates and are best placed within the order (as here) or outside it. See also: FOSSIL; MAMMALIA; PHYLOGENY; PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY; PRIMATES. Vast evidence suggests that the order Primates is a monophyletic group, that is, the primates have a common genetic origin. Although several peculiarities of the primate bauplan (body plan) appear to be inherited from an inferred common ancestor, it seems that the order as a whole is characterized by showing a variety of parallel adaptations in different groups to a predominantly arboreal lifestyle, including anatomical and behavioral complexes related to improved grasping and manipulative capacities, a variety of locomotor styles, and enlargement of the higher centers of the brain. Among the extant primates, the lower primates more closely resemble forms that evolved relatively early in the history of the order, whereas the higher primates represent a group that evolved more recently (Fig. 1). A classification of the primates, as accepted here, appears above. Early primates The earliest primates are placed in their own semiorder, Plesiadapiformes (as contrasted with the semiorder Euprimates for all living forms), because they have no direct evolutionary links with, and bear few adaptive resemblances to, any group of living primates. -

F a C T S H E

F A C T S H E E T Recent Primate Incidents Demonstrate Risks To Public Health and Safety, Animal Welfare November 2009 (Indiana): A woman was holding her 10-month-old granddaughter near an enclosure where a monkey was kept as a pet. The monkey pulled the hood of the girl’s coat, causing her head to strike the metal cage, and pulled her hair. The child was taken to the hospital and released that night. November 2009 (Tennessee): A capuchin monkey was found on a road. He had escaped from an SUV of a family vacationing in the area while they were eating at a restaurant, and was recaptured. November 2009 (Florida): A macaque monkey was on the loose outside a Pinellas County apartment complex. October 2009 (Kentucky): Authorities found a baboon being kept in the garage of a Kenton County home. The owners said they bought the animal from an Ohio dealer, and they surrendered her to a sanctuary. September 2009 (Florida): Authorities were looking for a pet patas monkey who had escaped from a Marion County home and been on the loose about two months. June 2009 (New Hampshire): An employee of a farm was severely bitten by a macaque monkey after leaving an enclosure unsecured. Macaques often carry Herpes B virus, and research published by the CDC concludes the health risk makes macaques unsuitable as pets. April 2009 (Oregon): A man brought a capuchin monkey in a diaper to a park. A 6-year-old girl approached and the animal jumped on her, causing two puncture wounds below her eye.