Jurassic Geology of the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New and Poorly Known Perisphinctoidea (Ammonitina) from the Upper Tithonian of Le Chouet (Drôme, SE France)

Volumina Jurassica, 2014, Xii (1): 113–128 New and poorly known Perisphinctoidea (Ammonitina) from the Upper Tithonian of Le Chouet (Drôme, SE France) Luc G. BULOT1, Camille FRAU2, William A.P. WIMBLEDON3 Key words: Ammonoidea, Ataxioceratidae, Himalayitidae, Neocomitidae, Upper Tithonian, Le Chouet, South-East France. Abstract. The aim of this paper is to document the ammonite fauna of the upper part of the Late Tithonian collected at the key section of Le Chouet (Drôme, SE France). Emphasis is laid on new and poorly known Ataxioceratidae, Himalayitidae and Neocomitidae from the upper part of the Tithonian. Among the Ataxioceratidae, a new account on the taxonomy and relationship between Paraulacosphinctes Schindewolf and Moravisphinctes Tavera is presented. Regarding the Himalayitidae, the range and content of Micracanthoceras Spath is discussed and two new genera are introduced: Ardesciella gen. nov., for a group of Mediterranean ammonites that is homoeomorphic with the Andean genus Corongoceras Spath, and Pratumidiscus gen. nov. for a specimen that shows morphological similarities with the Boreal genera Riasanites Spath and Riasanella Mitta. Finally, the occurrence of Neocomitidae in the uppermost Tithonian is documented by the presence of the reputedly Berriasian genera Busnardoiceras Tavera and Pseudargentiniceras Spath. INTRODUCTION known Perisphinctoidea from the Upper Tithonian of this reference section. Additional data on the Himalayitidae in- The unique character of the ammonite fauna of Le Chouet cluding the description and discussion of Boughdiriella (near Les Près, Drôme, France) (Fig. 1) has already been chouetensis gen. nov. sp. nov. are to be published elsewhere outlined by Le Hégarat (1973), but, so far, only a handful of (Frau et al., 2014). -

(Oxfordian) Bentonite Deposits in the Paris Basin and the Subalpine Basin, France

Sedimentology (2003) 50, 1035–1060 doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3091.2003.00592.x Characterization and correlation of Upper Jurassic (Oxfordian) bentonite deposits in the Paris Basin and the Subalpine Basin, France PIERRE PELLENARD*, JEAN-FRANCOIS DECONINCK*, WARREN D. HUFF , JACQUES THIERRYà, DIDIER MARCHANDà, DOMINIQUE FORTWENGLER§ and ALAIN TROUILLER– *Morphodynamique continentale et coˆtie`re, UMR 6143 CNRS, University of Rouen, Department of Earth Sciences, 76821 Mont St Aignan Cedex, France (E-mail: [email protected]) University of Cincinnati, Department of Geology, PO Box 210013, Cincinnati, OH 45221-00, USA àBioge´osciences-Dijon, UMR 5561CNRS, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Burgundy, 6 bd Gabriel, 21000 Dijon, France §Le Clos des Vignes, Quartier Perry, 26160 La Be´gude de Mazenc, France –ANDRA, Parc de la Croix Blanche, 1–7 rue Jean Monnet, 92298 Chaˆtenay-Malabry, France ABSTRACT Explosive volcanic activity is recorded in the Upper Jurassic of the Paris Basin and the Subalpine Basin of France by the identification of five bentonite horizons. These layers occur in Lower Oxfordian (cordatum ammonite zone) to Middle Oxfordian (plicatilis zone) clays and silty clays deposited in outer platform environments. In the Paris Basin, a thick bentonite (10–15 cm), identified in boreholes and in outcrop, is dominated by dioctahedral smectite (95%) with trace amounts of kaolinite, illite and chlorite. In contrast, five bentonites identified in the Subalpine Basin, where burial diagenesis and fluid circulation were more important, are composed of a mixture of kaolinite and regular or random illite/smectite mixed-layer clays in variable proportions, indicating a K-bentonite. In the Subalpine Basin, a 2–15 cm thick bentonite underlain by a layer affected by sulphate–carbonate mineralization can be correlated over 2000 km2. -

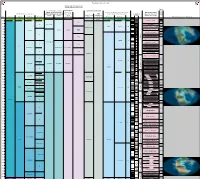

Expanded Jurassic Timescale

TimeScale Creator 2012 chart Russian and Ural regional units Russia Platform regional units Calca Jur-Cret boundary regional Russia Platform East Asian regional units reous stages - British and Boreal Stages (Jur- Australia and New Zealand regional units Marine Macrofossils Nann Standard Chronostratigraphy British regional Boreal regional Cret, Perm- Japan New Zealand Chronostratigraphy Geomagnetic (Mesozoic-Paleozoic) ofossil stages stages Carb & South China (Neogene & Polarity Tethyan Ammonoids s Ma Period Epoch Age/Stage Substage Cambrian) stages Cret) NZ Series NZ Stages Global Reconstructions (R. Blakey) Ryazanian Ryazanian Ryazanian [ no stages M17 CC2 Cretaceous Early Berriasian E Kochian Taitai Um designated ] M18 CC1 145 Berriasella jacobi M19 NJT1 Late M20 7b 146 Lt Portlandian M21 Durangites NJT1 M22 7a 147 Oteke Puaroan Op M22A Micracanthoceras microcanthum NJT1 Penglaizhenian M23 6b 148 Micracanthoceras ponti / Volgian Volgian Middle M24 Burckhardticeras peroni NJT1 Tithonian M24A 6a 149 M24B Semiformiceras fallauxi NJT15 M25 b E 150 M25A Semiformiceras semiforme NJT1 5a Early M26 Semiformiceras darwini 151 lt-Oxf N M-Sequence Hybonoticeras hybonotum 152 Ohauan Ko lt-Oxf R Kimmeridgian Hybonoticeras beckeri 153 m- Lt Late Oxf N Aulacostephanus eudoxus 154 m- NJT14 Late Aspidoceras acanthicum Oxf R Kimmeridgian Kimmeridgian Kimmeridgian Crussoliceras divisum 155 155.431 Card- N Ataxioceras hypselocyclum 156 E Early e-Oxf Sutneria platynota R Idoceras planula Suiningian 157 Cal- Oxf N Epipeltoceras bimammatum 158 lt- Lt Callo -

Stratigraphic Constraints on the Late Jurassic–Cretaceous Paleotectonic Interpretations of the Placetas Belt in Cuba, in C

Pszczo´łkowski, A., and R. Myczyn´ ski, 2003, Stratigraphic constraints on the Late Jurassic–Cretaceous paleotectonic interpretations of the Placetas belt in Cuba, in C. Bartolini, R. T. Buffler, and J. Blickwede, eds., The Circum-Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean: Hydrocarbon habitats, basin 25 formation, and plate tectonics: AAPG Memoir 79, p. 545–581. Stratigraphic Constraints on the Late Jurassic–Cretaceous Paleotectonic Interpretations of the Placetas Belt in Cuba Andrzej Pszczo´łkowski Institute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warszawa, Poland Ryszard Myczyn´ski Institute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warszawa, Poland ABSTRACT he Placetas belt in north-central Cuba consists of Late Jurassic–Cretaceous rocks that were highly deformed during the Paleocene to middle Eocene T arc-continent collision. The Late Proterozoic marble and Middle Jurassic granite are covered by the shallow-marine arkosic clastic rocks of late Middle Jurassic(?) or earliest Late Jurassic(?) ages. These arkosic rocks may be older than the transgressive arkosic deposits of the Late Jurassic–earliest Cretaceous Con- stancia Formation. The Berriasian age of the upper part of the Constancia For- mation in some outcrops at Sierra Morena and in the Jarahueca area does not confirm the Late Jurassic (pre-Tithonian) age of all deposits of this unit in the Placetas belt. The Tithonian and Berriasian ammonite assemblages are similar in the Placetas belt of north-central Cuba and the Guaniguanico successions in western Cuba. We conclude that in all paleotectonic interpretations, the Placetas, Camajuanı´, and Guaniguanico stratigraphic successions should be considered as biogeographically and paleogeographically coupled during the Tithonian and the entire Cretaceous. -

Jurassic-Cretaceous Tectonic and Depositional Evolution of the Forearc

International Geology Review ISSN: 0020-6814 (Print) 1938-2839 (Online) Journal homepage: https://tandfonline.com/loi/tigr20 The Byers Basin: Jurassic-Cretaceous tectonic and depositional evolution of the forearc deposits of the South Shetland Islands and its implications for the northern Antarctic Peninsula Joaquin Bastias, Mauricio Calderón, Lea Israel, Francisco Hervé, Richard Spikings, Robert Pankhurst, Paula Castillo, Mark Fanning & Raúl Ugalde To cite this article: Joaquin Bastias, Mauricio Calderón, Lea Israel, Francisco Hervé, Richard Spikings, Robert Pankhurst, Paula Castillo, Mark Fanning & Raúl Ugalde (2019): The Byers Basin: Jurassic-Cretaceous tectonic and depositional evolution of the forearc deposits of the South Shetland Islands and its implications for the northern Antarctic Peninsula, International Geology Review, DOI: 10.1080/00206814.2019.1655669 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00206814.2019.1655669 View supplementary material Published online: 21 Aug 2019. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tigr20 INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGY REVIEW https://doi.org/10.1080/00206814.2019.1655669 ARTICLE The Byers Basin: Jurassic-Cretaceous tectonic and depositional evolution of the forearc deposits of the South Shetland Islands and its implications for the northern Antarctic Peninsula Joaquin Bastias a,b, Mauricio Calderónc, Lea Israela, Francisco Hervéa,c, Richard -

Remarks on the Tithonian–Berriasian Ammonite Biostratigraphy of West Central Argentina

Volumina Jurassica, 2015, Xiii (2): 23–52 DOI: 10.5604/17313708 .1185692 Remarks on the Tithonian–Berriasian ammonite biostratigraphy of west central Argentina Alberto C. RICCARDI 1 Key words: Tithonian–Berriasian, ammonites, west central Argentina, calpionellids, nannofossils, radiolarians, geochronology. Abstract. Status and correlation of Andean ammonite biozones are reviewed. Available calpionellid, nannofossil, and radiolarian data, as well as radioisotopic ages, are also considered, especially when directly related to ammonite zones. There is no attempt to deal with the definition of the Jurassic–Cretaceous limit. Correlation of the V. mendozanum Zone with the Semiforme Zone is ratified, but it is open to question if its lower part should be correlated with the upper part of the Darwini Zone. The Pseudolissoceras zitteli Zone is characterized by an assemblage also recorded from Mexico, Cuba and the Betic Ranges of Spain, indicative of the Semiforme–Fallauxi standard zones. The Aulacosphinctes proximus Zone, which is correlated with the Ponti Standard Zone, appears to be closely related to the overlying Wind hauseniceras internispinosum Zone, although its biostratigraphic status needs to be reconsidered. On the basis of ammonites, radiolarians and calpionellids the Windhauseniceras internispinosum Assemblage Zone is approximately equivalent to the Suarites bituberculatum Zone of Mexico, the Paralytohoplites caribbeanus Zone of Cuba and the Simplisphinctes/Microcanthum Zone of the Standard Zonation. The C. alternans Zone could be correlated with the uppermost Microcanthum and “Durangites” zones, although in west central Argentina it could be mostly restricted to levels equivalent to the “Durangites Zone”. The Substeueroceras koeneni Zone ranges into the Occitanica Zone, Subalpina and Privasensis subzones, the A. -

1501 Rogov.Vp

Aulacostephanid ammonites from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of British Columbia (western Canada) and their significance for correlation and palaeobiogeography MIKHAIL A. ROGOV & TERRY P. POULTON We present the first description of aulacostephanid (Perisphinctoidea) ammonites from the Kimmeridgian of Canada, and the first illustration of these ammonites in the Americas. These ammonites include Rasenia ex gr. cymodoce, Zenostephanus (Xenostephanoides) thurrelli, and Zonovia sp. A from British Columbia (western Canada). They belong to genera that are widely distributed in the subboreal Eurasian Arctic and Northwest Europe, and they also occur even in those Boreal regions dominated by cardioceratids. They are important markers for a narrow stratigraphic interval in the Cymodoce Zone (top of Lower Kimmeridgian) and the lower part of the Mutabilis Zone (base of Upper Kimmeridgian) of the Northwest European standard succession. In Spitsbergen and Franz Josef Land, the only Upper Kimmeridgian aulacostephanid-bearing level is the Zenostephanus (Zenostephanus) sachsi biohorizon, which very likely belongs to the Mutabilis Zone. Expansion of Zenostephanus from Eurasia, where it is present over a large area, into British Columbia, is approximately correlative with a transgressive event that also led to expansion of the Submediterranean ammonite ge- nus Crussoliceras through the Submediterranean and Subboreal areas slightly before Zenostephanus. • Key words: Kimmeridgian, aulacostephanids, Zenostephanus, Rasenia, British Columbia, palaeobiogeography, sea-level changes. ROGOV, M.A. & POULTON, T.P. 2015. Aulacostephanid ammonites from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of British Columbia (western Canada) and their significance for correlation and palaeobiogeography. Bulletin of Geosciences 90(1), 7–20 (5 figures). Czech Geological Survey, Prague. ISSN 1214-1119. Manuscript received January 31, 2014; ac- cepted in revised form October 2, 2014; published online November 25, 2014; issued January 26, 2015. -

Geological Survey of Austria ©Geol

©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at und www.zobodat.at Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 120 Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, Benjamin Sames (Ed.) th 10 International Symposium on the Cretaceous: ABSTRACTS Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 120 www.geologie.ac.at Geological Survey of Austria ©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at und www.zobodat.at Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt (ISSN 1017-8880) Band 120 10th International Symposium on the Cretaceous Vienna, August 21–26, 2017 — ABSTRACTS BENJAMIN SAMES (Ed.) ©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at und www.zobodat.at Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 120 ISSN 1017-8880 Wien, im Juli 2017 10th International Symposium on the Cretaceous Vienna, August 21–26, 2017 – ABSTRACTS Benjamin Sames, Editor Dr. Benjamin Sames, Universität Wien, Department for Geodynamics and Sedimentology, Center for Earth Sciences, Althanstraße 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria. Recommended citation / Zitiervorschlag Volume / Gesamtwerk Sames, B. (Ed.) (2017): 10th International Symposium on the Cretaceous – Abstracts, 21–26 August 2017, Vienna. – Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 120, 351 pp., Vienna. Abstract (example / Beispiel) Granier, B., Gèze, R., Azar, D. & Maksoud, S. (2017): Regional stages: What is the use of them – A case study in Lebanon. – In: Sames, B. (Ed.): 10th International Symposium on the Cretaceous – Abstracts, 21–26 August 2017, Vienna. – Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, 120, 102, Vienna. Cover design: Monika Brüggemann-Ledolter (Geologische Bundesanstalt). Cover picture: Postalm section, upper Campanian red pelagic limestone-marl cycles (CORBs) of the Nierental Formation, Gosau Group, Northern Calcareous Alps (Photograph: M. Wagreich). 10th ISC Logo: Benjamin Sames The 10th ISC Logo is composed of selected elements of the Viennese skyline with, from left to right, the Stephansdom (St. -

Tithonian) Ammonites from the Spit! Shales in Western Zanskar(Nw Himalayas

Riv. It. Paleont. Strat. pp. 461-486 tav. 22-24 Febbraio 1991 UPPERJURASSIC (TITHONIAN) AMMONITES FROM THE SPIT! SHALES IN WESTERN ZANSKAR(NW HIMALAYAS) F. OLORIZ*& A. TINTORI** Key-word s: Paleoecology, Biostratigraphy, Ammonites, Upper Jurassic, Zanskar (NW Himalayas). Abstract. A description is given of the ammonites collected during the Italian expedition to the Zanskar region of the NW Himalayasin 1984 . The paleontological analysis is made in the context of a depositional and ecological model proposed for Spiti Shales fades. The genera Uhligites, "Vi-rgatosphinctes", Aulacosphinctesand Parapallasicerasare identified. An upper -to uppermost Lower Tithonian age is assigned for the highest levels of the Spiti Shales Fm. in the sector examined, although it may be possible that the extreme base of the Upper Tithonian is alsorepresented. Introduct ion and geological setting. This paper deals with a small ammonite fauna found near Sneatze (Western Zan skar) in the famous unit of the Spiti Shales. During the Italian geological expedition in Zanskar in the summer of 1984, one of us (A.T.) surveyed in particular the Jurassic units Qadoul et al., 1985; Gaetani et al., 1986). As regards the Mesozoic, most of the expedition took place in the Zangla Nappe (Baud et al., 1984), but a few observations were made also along the front of the Zum lung Nappe (Baud et al., 1984). Three main lithostratigraphic units are distinguishable between Ringdom Gompa and Tantak, even though they are often incompletely present as a result of the heavy tectonics of the area (Gaetani et al., 1985). The Kioto Limestone is uppermost Triassic-Late Liassic in age (Gaetani et al., 1986) and is rather poor in mac rofossils there. -

Earliest Known Lepisosteoid Extends the Range of Anatomically Modern Gars to the Late Jurassic Received: 25 September 2017 Paulo M

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Earliest known lepisosteoid extends the range of anatomically modern gars to the Late Jurassic Received: 25 September 2017 Paulo M. Brito1, Jésus Alvarado-Ortega2 & François J. Meunier3 Accepted: 2 December 2017 Lepisosteoids are known for their evolutionary conservatism, and their body plan can be traced at Published: xx xx xxxx least as far back as the Early Cretaceous, by which point two families had diverged: Lepisosteidae, known since the Late Cretaceous and including all living species and various fossils from all continents, except Antarctica and Australia, and Obaichthyidae, restricted to the Cretaceous of northeastern Brazil and Morocco. Until now, the oldest known lepisosteoids were the obaichthyids, which show general neopterygian features lost or transformed in lepisosteids. Here we describe the earliest known lepisosteoid (Nhanulepisosteus mexicanus gen. and sp. nov.) from the Upper Jurassic (Kimmeridgian – about 157 Myr), of the Tlaxiaco Basin, Mexico. The new taxon is based on disarticulated cranial pieces, preserved three-dimensionally, as well as on scales. Nhanulepisosteus is recovered as the sister taxon of the rest of the Lepisosteidae. This extends the chronological range of lepisosteoids by about 46 Myr and of the lepisosteids by about 57 Myr, and flls a major morphological gap in current understanding the early diversifcation of this group. Actinopterygians, or ray-finned fishes, are the largest group among extant gnathostoms vertebrates. Today actinopterygians are represented by three major clades: Cladistia (bichirs and rope fsh), with at least 16 species, Chondrostei (sturgeons and paddle fshes), with about 30 species, and Neopterygii, formed by the Teleostei, with about 30,000 species and the Holostei with eight species: one halecomorph (bowfn) and 7 ginglymodians (gars)1. -

Annual Meeting 2002

Newsletter 51 74 Newsletter 51 75 The Palaeontological Association 46th Annual Meeting 15th–18th December 2002 University of Cambridge ABSTRACTS Newsletter 51 76 ANNUAL MEETING ANNUAL MEETING Newsletter 51 77 Holocene reef structure and growth at Mavra Litharia, southern coast of Gulf of Corinth, Oral presentations Greece: a simple reef with a complex message Steve Kershaw and Li Guo Oral presentations will take place in the Physiology Lecture Theatre and, for the parallel sessions at 11:00–1:00, in the Tilley Lecture Theatre. Each presentation will run for a New perspectives in palaeoscolecidans maximum of 15 minutes, including questions. Those presentations marked with an asterisk Oliver Lehnert and Petr Kraft (*) are being considered for the President’s Award (best oral presentation by a member of the MONDAY 11:00—Non-marine Palaeontology A (parallel) Palaeontological Association under the age of thirty). Guts and Gizzard Stones, Unusual Preservation in Scottish Middle Devonian Fishes Timetable for oral presentations R.G. Davidson and N.H. Trewin *The use of ichnofossils as a tool for high-resolution palaeoenvironmental analysis in a MONDAY 9:00 lower Old Red Sandstone sequence (late Silurian Ringerike Group, Oslo Region, Norway) Neil Davies Affinity of the earliest bilaterian embryos The harvestman fossil record Xiping Dong and Philip Donoghue Jason A. Dunlop Calamari catastrophe A New Trigonotarbid Arachnid from the Early Devonian Windyfield Chert, Rhynie, Philip Wilby, John Hudson, Roy Clements and Neville Hollingworth Aberdeenshire, Scotland Tantalizing fragments of the earliest land plants Steve R. Fayers and Nigel H. Trewin Charles H. Wellman *Molecular preservation of upper Miocene fossil leaves from the Ardeche, France: Use of Morphometrics to Identify Character States implications for kerogen formation Norman MacLeod S. -

Redalyc.Upper Jurassic Ammonites and Bivalves from the Cucurpe

Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas ISSN: 1026-8774 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Villaseñor, Ana Bertha; González Léon, Carlos M.; Lawton, Timothy F.; Aberhan, Martin Upper Jurassic ammonites and bivalves from the Cucurpe Formation, Sonora (Mexico) Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, vol. 22, núm. 1, 2005, pp. 65-87 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Querétaro, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=57222107 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas,Upper v. 22, Jurassic núm. 1, ammonites 2005, p. 65-87 and bivalves from Sonora 65 Upper Jurassic ammonites and bivalves from the Cucurpe Formation, Sonora (Mexico) Ana Bertha Villaseñor1,*, Carlos M. González-León2, Timothy F. Lawton3, and Martin Aberhan4 1 Departamento de Paleontología, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, 04510 México, D. F., Mexico. 2 Estación Regional del Noroeste, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 83000 Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico. 3 Department of Geological Sciences, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA. 4 Museum für Naturkunde, Zentralinstitut der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institut für Paläontologie, Invalidenstr. 43, D-10115 Berlin, Germany. * [email protected] ABSTRACT Four new molluscan assemblages from north-central Sonora indicate that the Cucurpe Formation ranges in age from late Oxfordian to early Tithonian. These assemblages extend the known paleogeographic range of Late Jurassic Tethyan fossil groups several hundred km to the northwest and improve correlation of Upper Jurassic strata in northern Mexico.