From Assyria to Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015–2016 Annual Report

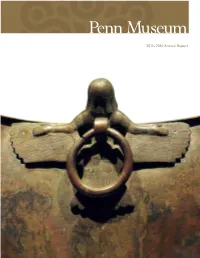

2015–2016 Annual Report 2015–2016 Annual Report 3 EXECUTIVE MESSAGE 4 THE NEW PENN MUSEUM 7 YEAR IN REVIEW 8 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE GEOGRAPHY 8 Teaching & Research: Penn Museum-Sponsored Field Projects 10 Excavations at Anubis-Mountain, South Abydos (Egypt) 12 Gordion Archaeological Project (Turkey) — Historical Landscape Preservation at Gordion — Gordion Cultural Heritage Education Project 16 The Penn Cultural Heritage Center — Conflict Culture Research Network (Global) — Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria & Iraq Project (Syria and Iraq) — Tihosuco Heritage Preservation & Community Development Project (Mexico) — Wayka Heritage Project (California, USA) 20 Pelekita Cave in Eastern Crete (Greece) 21 Late Pleistocene Pyrotechnology (France) 22 The Life & Times of Emma Allison (Canada) 23 On the Wampum Trail (North America) 24 Louis Shotridge & the Penn Museum (Alaska, USA) 25 Smith Creek Archaeological Project (Mississippi, USA) 26 Silver Reef Project (Utah, USA) 26 South Jersey (Vineland) Project (New Jersey, USA) 27 Collections: New Acquisitions 31 Collections: Outgoing Loans & Traveling Exhibitions 35 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE NUMBERS 40 PENN MUSEUM 2015–2016: BY THE MONTH 57 SUPPORTING THE MISSION 58 Leadership Supporters 62 Loren Eiseley Society 64 Expedition Circle 66 The Annual Fund 67 Sara Yorke Stevenson Legacy Circle 68 Corporate, Foundation, & Government Agency Supporters Objects on the cover, inside cover, and above were featured 71 THE GIFT OF TIME in the special exhibition The Golden Age of King Midas, from 72 Exhibition Advisors & Contributors February 13, 2016 through November 27, 2016. 74 Penn Museum Volunteers On the cover: Bronze cauldron with siren and demon 76 Board of Overseers attachments. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations 18516. -

Virtual Assyria Dan Lundberg

Virtual Assyria Dan Lundberg (The content of this site is based on data collected 1996-1997) Illustration: Ann Ahlbom Sundqvist Introduction (2010) Some comments on the re-publishing of this study of Assyrian cultural activities on the Internet – more than 10 years later. This study is based on fieldwork and other data collections that I conducted during the second half of the 1990s. I can truly say that I was impressed by all the web enthusiasts that were striving to create a transnational Assyrian community – a "cyber nation" on the Internet. However, the development has been incredibly fast during the last decades and today (2010) it is hard to imagine the almost science fictional impression that ideas about cyber communities gave back in the nineties. When looking back at the development of the Internet it seems as if the "cyber space" that was announced on the home page of Nineveh On-line 1997 has become less virtual over the years. Today we are living in both worlds – using the Internet for shopping, reading, finding information, communication, playing, dating, etc, etc.The boarder between virtual and real often appears to be diffuse and in fact, not so important any more. Svenskt visarkiv shut down this website in 2008 because we felt we could no longer guarantee that all links were relevant and functioning. The lifespan of articles online can sometimes be quite short. However, we have received many requests to publish it again, an indication that the content is still regarded as important. This new edition has some corrected links and dead links have been deleted, but otherwise the text has not been changed at all. -

Download PDF Version of Article

STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila HELSINKI 2009 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS AND SCHOLARS clay or on a writing board and the other probably in Aramaic onleather in andtheotherprobably clay oronawritingboard ME FRONTISPIECE 118882. Assyrian officialandtwoscribes;oneiswritingincuneiformo . n COURTESY TRUSTEES OF T H E BRITIS H MUSEUM STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY Vol. 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila Helsinki 2009 Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Studia Orientalia, Vol. 106. 2009. Copyright © 2009 by the Finnish Oriental Society, Societas Orientalis Fennica, c/o Institute for Asian and African Studies P.O.Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 B) FIN-00014 University of Helsinki F i n l a n d Editorial Board Lotta Aunio (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Librarian of the Society) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Secretary of the Society) -

Possible Historical Traces in the Doctrina Addai

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, Vol. 9.1, 51-127 © 2006 [2009] by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute and Gorgias Press POSSIBLE HISTORICAL TRACES IN THE DOCTRINA ADDAI ILARIA L. E. RAMELLI CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF THE SACRED HEART, MILAN 1 ABSTRACT The Teaching of Addai is a Syriac document convincingly dated by some scholars in the fourth or fifth century AD. I agree with this dating, but I think that there may be some points containing possible historical traces that go back even to the first century AD, such as the letters exchanged by king Abgar and Tiberius. Some elements in them point to the real historical context of the reign of Abgar ‘the Black’ in the first century. The author of the Doctrina might have known the tradition of some historical letters written by Abgar and Tiberius. [1] Recent scholarship often dates the Doctrina Addai, or Teaching of Addai,2 to the fourth century AD or the early fifth, a date already 1 This is a revised version of a paper delivered at the SBL International Meeting, Groningen, July 26 2004, Ancient Near East section: I wish to thank very much all those who discussed it and so helped to improve it, including the referees of the journal. 2 Extant in mss of the fifth-sixth cent. AD: Brit. Mus. 935 Add. 14654 and 936 Add. 14644. Ed. W. Cureton, Ancient Syriac Documents (London 1864; Piscataway: Gorgias, 2004 repr.), 5-23; another ms. of the sixth cent. was edited by G. Phillips, The Doctrine of Addai, the Apostle (London, 1876); G. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

The Parthian-Roman Bipolarism: Some Considerations for a Historical Perspective

Revista Mundo Antigo – Ano IV, V. 4, N° 08 – Dezembro – 2015 – ISSN 2238-8788 The Parthian-Roman bipolarism: some considerations for a historical perspective. Giacomo Tabita1 Submetido em Novembro/2015 Aceito em Novembro/2015 ABSTRACT: During the 1st-3rd centuries AD the Euphrates’s River was the so-called Latin Limes of the late Roman Empire (Isaac 1988: 124-147; Frezouls 1980: 357-386, 371; Gray 1973: 24-40; Mayerson 1986: 35-47; Invernizzi 1986: 357-381; Valtz 1987: 81-89), understood as a dynamic geo-political and cultural border with both military and trading function, where the interfaced cultural areas were defined by the coexistence, interaction and conflict of several ideologies which are at the basis of the fights between Romans and Parthians aiming to the control of the territories on the Middle-Euphrates’s area. Rome occupied Dura Europos during the AD 165 obtaining the control on the Euphrates area and during the AD 194-195 and AD 197-199 Septimius Severus enlarged the extension of the areas controlled by Rome, overlapping on the limit of the Euphrates, therefore determining the Parthian giving ground on the Middle Euphrates (Oates 1968: 67-92). The strategic advantage obtained by the Romans allowed them also to build the fortified post of Kifrin (Valtz 1987: 81-89), seen from a political and military point of view as a means to enforce and to advance the eastern frontier of the empire on the pre-existent settlement. KEYWORDS: 3rd century AD,_Middle Euphrates,_Romans, _Parthians,_Septimius Severus. 1 Ph.D at Turin University and actually he is an affiliated member at the Heritage research group of the Cambridge University (UK), Archaeologist, e-mail address: [email protected] NEHMAAT http://www.nehmaat.uff.br 131 http://www.pucg.uff.br CHT/UFF-ESR Revista Mundo Antigo – Ano IV, V. -

The Origin of the Terms 'Syria(N)'

Parole de l’Orient 36 (2011) 111-125 THE ORIGIN OF THE TERMS ‘SYRIA(N)’ & SŪRYOYO ONCE AGAIN BY Johny MESSO Since the nineteenth century, a number of scholars have put forward various theories about the etymology of the basically Greek term ‘Syrian’ and its Aramaic counterpart Sūryoyo1. For a proper understanding of the his- tory of these illustrious names in the two different languages, it will prove useful to analyze their backgrounds separately from one another. First, I will discuss the most persuasive theory as regards the origin of the word ‘Syria(n)’. Secondly, two hypotheses on the Aramaic term Sūryoyo will be examined. In the final part of this paper, a new contextual backdrop and sharply demarcated period will be proposed that helps us to understand the introduction of this name into the Aramaic language. 1. THE ETYMOLOGY OF THE GREEK TERM FOR ‘SYRIA(N)’ Due to their resemblance, the ancient Greeks had always felt that ‘Syr- ia(n)’ and ‘Assyria(n)’ were somehow onomastically related to each other2. Nöldeke was the first modern scholar who, in 1871, seriously formulated the theory that in Greek ‘Syria(n)’ is a truncated form of ‘Assyria(n)’3. Even if his view has a few minor difficulties4, most writers still adhere to it. 1) Cf., e.g., the review (albeit brief and inexhaustive) by A. SAUMA, “The origin of the Word Suryoyo-Syrian”, in The Harp 6:3 (1993), pp. 171-197; R.P. HELM, ‘Greeks’ in the Neo-Assyrian Levant and ‘Assyria’ in Early Greek Writers (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation; University of Pennsylvania, 1980), especially chapters 1-2. -

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE and HERITAGE Basra Its History, Culture and Heritage

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE CULTURE : ITS HISTORY, BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins Edited by Paul Collins BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins © BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ 2019 ISBN 978-0-903472-36-4 Typeset and printed in the United Kingdom by Henry Ling Limited, at the Dorset Press, Dorchester, DT1 1HD CONTENTS Figures...................................................................................................................................v Contributors ........................................................................................................................vii Introduction ELEANOR ROBSON .......................................................................................................1 The Mesopotamian Marshlands (Al-Ahwār) in the Past and Today FRANCO D’AGOSTINO AND LICIA ROMANO ...................................................................7 From Basra to Cambridge and Back NAWRAST SABAH AND KELCY DAVENPORT ..................................................................13 A Reserve of Freedom: Remarks on the Time Visualisation for the Historical Maps ALEXEI JANKOWSKI ...................................................................................................19 The Pallakottas Canal, the Sealand, and Alexander STEPHANIE -

The Catalyst for Warfare: Dacia's Threat to the Roman Empire

The Catalyst for Warfare: Dacia’s Threat to the Roman Empire ______________________________________ ALEXANDRU MARTALOGU The Roman Republic and Empire survived for centuries despite imminent threats from the various peoples at the frontiers of their territory. Warfare, plundering, settlements and other diplomatic agreements were common throughout the Roman world. Contemporary scholars have given in-depth analyses of some wars and conflicts. Many, however, remain poorly analyzed given the scarce selection of period documents and subsequent inquiry. The Dacian conflicts are one such example. These emerged under the rule of Domitian1 and were ended by Trajan2. Several issues require clarification prior to discussing this topic. The few sources available on Domitian’s reign describe the emperor in hostile terms.3 They depict him as a negative figure. By contrast, the rule of Trajan, during which the Roman Empire reached its peak, is one of the least documented reigns of a major emperor. The primary sources necessary to analyze the Dacian wars include Cassius Dio’s Roman History, Jordanes’ Getica and a few other brief mentions by several ancient authors, including Pliny the Younger and Eutropius. Pliny is the only author contemporary to the wars. The others inherited an already existing opinion about the battles and emperors. It is no surprise that scholars continue to disagree on various issues concerning the Dacian conflicts, including the causes behind Domitian’s and Trajan’s individual decisions to attack Dacia. This study will explore various possible causes behind the Dacian Wars. A variety of reasons lead some to believe that the Romans felt threatened by the Dacians. -

"The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah." Israel and Empire: a Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism

"The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah." Israel and Empire: A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism. Perdue, Leo G., and Warren Carter.Baker, Coleman A., eds. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015. 37–68. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780567669797.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 16:38 UTC. Copyright © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah I. Historical Introduction1 When the installation of a new monarch in the temple of Ashur occurs during the Akitu festival, the Sangu priest of the high god proclaims when the human ruler enters the temple: Ashur is King! Ashur is King! The ruler now is invested with the responsibilities of the sovereignty, power, and oversight of the Assyrian Empire. The Assyrian Empire has been described as a heterogeneous multi-national power directed by a superhuman, autocratic king, who was conceived of as the representative of God on earth.2 As early as Naram-Sin of Assyria (ca. 18721845 BCE), two important royal titulars continued and were part of the larger titulary of Assyrian rulers: King of the Four Quarters and King of All Things.3 Assyria began its military advances west to the Euphrates in the ninth century BCE. -

Biblical Assyria and Other Anxieties in the British Empire Steven W

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Libraries Libraries & Educational Technologies 2001 Biblical Assyria and Other Anxieties in the British Empire Steven W. Holloway James Madison University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/letfspubs Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation “Biblical Assyria and Other Anxieties in the British Empire,” Journal of Religion & Society (http://moses.creighton.edu/jrs/2001/ 2001-12.pdf) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries & Educational Technologies at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Libraries by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Religion & Society Volume 3 (2001) ISSN 1522-5658 Biblical Assyria and Other Anxieties in the British Empire Steven W. Holloway, American Theological Library Association and Saint Xavier University, Chicago Abstract The successful “invasion” of ancient Mesopotamia by explorers in the pay of the British Museum Trustees resulted in best-selling publications, a treasure-trove of Assyrian antiquities for display purposes and scholarly excavation, and a remarkable boost to the quest for confirmation of the literal truth of the Bible. The public registered its delight with the findings through the turnstyle- twirling appeal of the British Museum exhibits, and a series of appropriations of Assyrian art motifs and narratives in popular culture - jewelry, bookends, clocks, fine arts, theater productions, and a walk-through Assyrian palace among other period mansions at the Sydenham Crystal Palace. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Personal Name: John R. Alden Address: 1215 Lutz Ave., Ann Arbor, MI 48103 Phone/e-mail: (734) 223-7668; [email protected] Education B.S. Cornell University, 1969 -- Chemical Engineering A.M. University of Pennsylvania, 1973 -- Anthropology Ph.D. University of Michigan, 1979 -- Anthropology Academic Employment 1979-80 Visiting Assistant Professor, Duke University Department of Anthropology teaching introductory level courses on archeology and human evolution and upper level undergraduate courses on regional analysis and the archeology of complex societies 1992-2013 Adjunct Associate Research Scientist, Univ. of MI Museum of Anthropology 2013-present Research Affiliate, Univ. of MI Museum of Anthropological Archaeology Grants and Fellowships 1976 NSF Dissertation Improvement Grant, #BNS-76-81955 1978 Dissertation Year Fellowship, University of Michigan 1991 National Geographic Society Research Grant, "Mapping Inka Installations in the Atacama," with Thomas F. Lynch, P. I. 2003 National Geographic Society Research Grant #7429-03, “Politics, Trade, and Regional Economy in the Bronze Age Central Zagros,” with Kamyar Abdi, P. I. 2008 White-Levy Program for Archaeological Publications Grant, “Excavations in the GHI Area of Tal-e Malyan, Fars Province, Iran.” 2009 White-Levy Program for Archaeological Publications Grant, 2nd year of funding Publications 1973 The Question of Trade in Proto-Elamite Iran. A.M. Thesis, Univ. of Pennsylvania Dept. of Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA. 1977 "Surface Survey at Quachilco." In R. D. Drennan, ed., The Palo Blanco Project: A Report on the 1975 and 1976 Seasons in the Tehuacán Valley, pp. 16-22. Univ. of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Ann Arbor, MI. 1978 "A Sasanian Kiln From Tal-i Malyan, Fars." Iran XVI: 127-133.