Record of Decision Oil & Gas Leasing U.S. Forest Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinedale Region Angler Newsletter

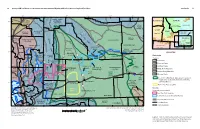

Wyoming Game and Fish Department 2013 Edition Volume 9 Pinedale Region Angler Newsletter Inside this issue: Burbot Research to Begin in 1 2013 New Fork River Access Im- 2 provements Thanks for reading the 2013 version of Pinedale ND South Dakota Know Your Natives: Northern 3 Region Angler Newsletter. This newsletter is Yellowstone Montana Leatherside intended for everyone interested in the aquatic Natl. Park Sheridan resources in the Pinedale area. The resources we Cody Fire and Fisheries 4 Gillette Idaho manage belong to all of us. Jackson Gannett Peak Wyoming Riverton Nebraska Watercraft Inspections in 2013 6 The Pinedale Region encompasses the Upper Pinedale Casper Green River Drainage (upstream of Fontenelle Lander Elbow Lake 7 Rawlins Reservoir) and parts of the Bear River drainage Green Rock Springs Cheyenne 2013 Calendar 8 near Cokeville (see map). River Laramie Colorado Utah 120 mi Pinedale Region Map Pinedale Region Fisheries Staff: Fisheries Management Burbot Research Begins on the Green River in 2013 Hilda Sexauer Fisheries Supervisor Pete Cavalli Fisheries Biologist Darren Rhea Fisheries Biologist Burbot, also known as “ling”, are a species of fisheries. Adult burbot are a voracious preda- fish in the cod family with a native range that tor and prey almost exclusively on other fish or Aquatic Habitat extends into portions of north-central Wyoming crayfish. Important sport fisheries in Flaming Floyd Roadifer Habitat Biologist including the Wind and Bighorn River drain- Gorge, Fontenelle, and Big Sandy reservoirs ages. While most members of the cod family have seen dramatic changes to some sport fish Spawning reside in the ocean, this specialized fish has and important forage fish communities. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2017 to 09/30/2017 Bridger-Teton National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Bridger-Teton National Forest Big Piney Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) R4 - Intermountain Region Exxon/Mobil Lake Ridge Well - Minerals and Geology On Hold N/A N/A Justin Snyder T67X-14G1 307 367 5740 EA [email protected] Description: Authorize a Surface Use Plan of Operation to drill one natural gas exploratory well on an existing unit and lease. Location: UNIT - Big Piney Ranger District. STATE - Wyoming. COUNTY - Lincoln. LEGAL - T28N, R115W, Sec. 14, 6th P.M. 20 miles west of Big Piney, Wyoming. North Piney Post and Pole - Forest products Developing Proposal Expected:09/2017 09/2017 Dundonald Cochrane CE Est. Scoping Start 07/2017 307-276-5814 [email protected] Description: Commercial thinning of 70 ac. of lodgepole pine and mixed conifers to the west of Apperson Creek. Project proposes to increase structural diversity, manage hazardous fuel loading, & salvage forest products. Construct a half mile of temporary roads. Location: UNIT - Big Piney Ranger District. STATE - Wyoming. COUNTY - Sublette. LEGAL - T31, R115, Sec. 10,11,14,15. About 25 miles northwest of Big Piney, WY, in the Upper North Piney Creek watershed to the west of Apperson Creek and Forest Road 10370. Old Indian Trail Maki Creek - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:07/2017 08/2017 Chad Hayward Crossing - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Scoping Start 02/02/2015 307-367-5723 CE [email protected] Description: The Forest Service proposes to construct a bridge for both recreation use and livestock crossing on the Old Indian Trail at the Maki Creek stream crossing. -

Mineral Occurrence and Development Potential Report Rawlins Resource

CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Purpose of Report ............................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Lands Involved and Record Data ....................................................................................1-2 2.0 DESCRIPTION OF GEOLOGY ...............................................................................................2-1 2.1 Physiography....................................................................................................................2-1 2.2 Stratigraphy ......................................................................................................................2-3 2.2.1 Precambrian Era....................................................................................................2-3 2.2.2 Paleozoic Era ........................................................................................................2-3 2.2.2.1 Cambrian System...................................................................................2-3 2.2.2.2 Ordovician, Silurian, and Devonian Systems ........................................2-5 2.2.2.3 Mississippian System.............................................................................2-5 2.2.2.4 Pennsylvanian System...........................................................................2-5 2.2.2.5 Permian System.....................................................................................2-6 -

Guide to the Willows of Shoshone National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Willows Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station of Shoshone National General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-83 Forest October 2001 Walter Fertig Stuart Markow Natural Resources Conservation Service Cody Conservation District Abstract Fertig, Walter; Markow, Stuart. 2001. Guide to the willows of Shoshone National Forest. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-83. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 79 p. Correct identification of willow species is an important part of land management. This guide describes the 29 willows that are known to occur on the Shoshone National Forest, Wyoming. Keys to pistillate catkins and leaf morphology are included with illustrations and plant descriptions. Key words: Salix, willows, Shoshone National Forest, identification The Authors Walter Fertig has been Heritage Botanist with the University of Wyoming’s Natural Diversity Database (WYNDD) since 1992. He has conducted rare plant surveys and natural areas inventories throughout Wyoming, with an emphasis on the desert basins of southwest Wyoming and the montane and alpine regions of the Wind River and Absaroka ranges. Fertig is the author of the Wyoming Rare Plant Field Guide, and has written over 100 technical reports on rare plants of the State. Stuart Markow received his Masters Degree in botany from the University of Wyoming in 1993 for his floristic survey of the Targhee National Forest in Idaho and Wyoming. He is currently a Botanical Consultant with a research emphasis on the montane flora of the Greater Yellowstone area and the taxonomy of grasses. Acknowledgments Sincere thanks are extended to Kent Houston and Dave Henry of the Shoshone National Forest for providing Forest Service funding for this project. -

Wind River Expedition Through the Wilderness… a Journey to Holiness July 17-23, 2016

Wind River Expedition Through the Wilderness… a Journey to Holiness July 17-23, 2016 Greetings Mountain Men, John Muir once penned the motivational quote… “The mountains are calling and I must go.” And while I wholeheartedly agree with Muir, I more deeply sense that we are responding to the “Still Small Voice”, the heart of God calling us upward to high places. And when God calls we must answer, for to do so is to embark on an adventure like no other! Through the mountain wilderness Moses, Elijah, and Jesus were all faced with the holiness and power of God. That is our goal and our deepest desire. Pray for nothing short of this my friends and be ready for what God has in store… it’s sure to be awesome! Please read the entire information packet and then follow the simple steps below and get ready! Preparing for the Expedition: Step 1 Now Pay deposit of $100 and submit documents by April 30, 2017 Step 2 Now Begin fitness training! Step 3 Now Begin acquiring gear! (see following list) Step 4 May 31 Pay the balance of expedition $400 Step 5 June 1 Purchase airline ticket (see directions below) Step 6 July 17 Fly to Salt Lake City! (see directions below) Step 7 July 17-23 Wind River Expedition (see itinerary below) Climb On! Marty Miller Blueprint for Men Blueprint for Men, Inc. 2017 © Logistics Application Participant Form - send PDF copy via email to [email protected] Release Form – send PDF copy via email to [email protected] Medical Form – send PDF copy to [email protected] Deposit of $100 – make donation at www.blueprintformen.org Deadline is April 30, 2017 Flight to Denver If you live in the Chattanooga area I recommend that you fly out of Nashville (BNA) or Atlanta (ATL) on Southwest Airlines (2 free big bags!) to Salt Lake City (SLC) on Sun, July 17. -

Inventory of Rock Glaciers in the American West and Their Topography and Climate

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 12-30-2020 Inventory of Rock Glaciers in the American West and Their Topography and Climate Allison Reese Trcka Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geology Commons, and the Geomorphology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Trcka, Allison Reese, "Inventory of Rock Glaciers in the American West and Their Topography and Climate" (2020). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5637. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7509 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Inventory of Rock Glaciers in the American West and Their Topography and Climate by Allison Reese Trcka A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology Thesis Committee: Andrew G. Fountain Chair Adam Booth Martin Lafrenz Portland State University 2020 Abstract Rock glaciers are flowing geomorphic landforms composed of an ice/debris mixture. A uniform rock glacier classification scheme was created for the western continental US, based on internationally recognized criteria, to merge the various regional published inventories. A total of 2249 rock glaciers (1564 active, 685 inactive) and 7852 features of interest were identified in 10 states (WA, OR, CA, ID, NV, UT, ID, MT, WY, CO, NM). Sulfur Creek rock glacier in Wyoming is the largest active rock glacier (2.39 km2). -

Lakeside Lodge Opportunity Cabins | Restaurant | Bar | Marina PINEDALE, WY

Offering Memorandum For Sale | Investment Lakeside Lodge Opportunity Cabins | Restaurant | Bar | Marina PINEDALE, WY Offered by: John Bushnell 801.947.8300 Colliers International 6550 S Millrock Dr | Suite 200 Salt Lake City, UT 84121 P: +1 801 947 8300 Table of Contents 1. LAKESIDE LODGE RESORT AND MARINA 2. FREMONT LAKE 3. PINEDALE AND SURROUNDING AREA 4. ANNUAL SAILBOAT REGATTA AND FISHING DERBIES 5. ANNUAL MOUNTAIN MAN RENDEZVOUS 6. WIND RIVER AND BRIDGER TETON NATURAL FOREST 7. REGIONAL INFORMATION 8. WEDDINGS AT LAKESIDE 9. INCOME AND PERFORMANCE This document has been prepared by Colliers International for advertising and general information only. Colliers International makes no guarantees, representations or warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, regarding the information including, but not limited to, warranties of content, accuracy and reliability. Any interested party should undertake their own inquiries as to the accuracy of the information. Colliers International excludes unequivocally all inferred or implied terms, conditions and warranties arising out of this document and excludes all liability for loss and damages arising there from. This publication is the copyrighted property of Colliers International and/or its licensor(s). ©2018. All rights reserved. LAKESIDE LODGE | SALE OFFERING COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL P. 3 LAKESIDE LODGE - PINEDALE, WY Lakeside Lodge Resort and Marina ADDRESS: Lakeside Lodge Resort and Marina 99 FS RD 111 Fremont Lake Rd POB 1819 Pinedale, WY 82941 Web Site: www.lakesidelodge.com PROPERTY DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION: Lakeside Lodge is a full service resort located 4 miles north of Pinedale, Wyoming and 75 miles south of Jackson Hole and Teton National Park, Wyoming and 110 miles south of Yellowstone National Park. -

Planner Shoshone National Forest 808 Meadow Lane Avenue Cody, WY 82414

Responsible official Daniel J. Jirón Regional Forester Rocky Mountain Region 740 Simms Street Golden, CO 80401 For more information Joseph G. Alexander Forest supervisor Shoshone National Forest 808 Meadow Lane Avenue Cody, WY 82414 Olga G. Troxel Acting Forest Planner Shoshone National Forest 808 Meadow Lane Avenue Cody, WY 82414 Telephone: 307.527.6241 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Terms used in this document .................................................................................................................. -

Mule Deer Assessment

The Red Desert to Hoback MULE DEER MIGRATION ASSESSMENT HALL SAWYER MATTHEW HAYES BILL RUDD MATTHEW KAUFFMAN pring is not yet here, but one can feel winter loosening its grip on Wyoming. Soon the snow will melt and the Smountains will turn a vibrant green, flush with grasses and forbs. And soon, Wyoming’s iconic ungulates will leave their low-elevation winter ranges and head up to the mountains, knowing they will find abundant forage there. Elk near Cody will travel west into Yellowstone; some of them mingling with moose arriving from as far south as Jackson. Near Dubois, bighorn sheep will start to follow the receding snow into the craggy peaks of the northern Winds. Down on the sagebrush steppe south of Pinedale, pronghorn and mule deer will begin their migrations toward the Wyoming Range, the Gros Ventre Range, and Grand Teton National Park. Throughout the state, the arrival of spring will set Wyoming’s ungulate herds in motion once again. These long-distance move- ments are not only spectacular; they also allow our herds to exist in such high numbers. The more we learn, the more these animals surprise us. Recently, wildlife researcher Hall Sawyer worked with the BLM to collar what they thought was a resident herd of mule deer living near Rock Springs. Remarkably, they discovered that those deer undertake the longest migration ever recorded in the Lower 48, connecting the sage- brush steppe of the Red Desert with the mountain meadows of the Hoback Basin. This report is an assessment of their remarkable journey and the obstacles these deer encounter along the way. -

Introduction 13

12 Geology and Mineral Resources of the Southwestern and South-Central Wyoming and Bear River Watershed Sagebrush Focal Areas Introduction 13 112°0' 111°0' 110°0' 109°0' 108°0' 107°0' MIDDLE ROCKY 43°30' COLUMBIA MOUNTAINS WASHINGTON MONTANA PLATEAU PROVINCE PROVINCE GREAT NORTHERN GREAT PLAINS PLAINS ROCKY MOUNTAINS PROVINCE COLUMBIA PLATEAU IDAHO BINGHAM BONNEVILLE MIDDLE ROCKY Map COUNTY MOUNTAINS COUNTY WIND RIVER RANGE OREGON area 43°0' BANNOCK WYOMING RANGE NATRONA WYOMING COUNTY BASIN AND RANGE FREMONT COUNTY COUNTY PROVINCE WYOMING 287 Study areas BASIN CARIBOU COUNTY RATTLESNAKE HILLS BASIN AND RANGE SOUTH PASS NEVADA UTAH COLORADO SUBLETTE BLOCK Sweetwater River GRANITE COUNTY 30 MOUNTAINS 42°30' IDAHO EXPLANATION 89 BIG SANDY BEAR LAKE LINCOLN BLOCK 191 Physiography COUNTY COUNTY 189 Crooks Gap FERRIS FRANKLIN Provinces COUNTY MOUNTAINS FOSSIL BASIN Great Plains 30 89 BLOCK Basin and Range BOARS TUSK Columbia Plateau 42°0' Bear CARBON CONTINENTAL WYOMING BASIN COUNTY BOX Lake FONTENELLE BLOCK Middle Rocky Mountains TUNP RANGE PROVINCE ELDER BLOCK DIVIDE BLOCK COUNTY CACHE VALLEY Southern Rocky Mountains LEUCITE GREEN Rawlins HILLS 30 RIVER 80 Wyoming Basin 191 BASIN MTS. UTAH BEAR RIVER RANGE Sand Greater Green River Basin (Approximate boundary of Bear River CRAWFORD Basin Bridger, Great Divide, Kindt, Washakie, Green River, CACHE Rock Springs SOUTHERN 41°30' COUNTY 189 ROCKY and Hoback Basins) BEAR LAKE Green River MOUNTAINS GREAT Trona mineralized area outline RICH PLATEAU 191 PROVINCE COUNTY BLOCK Base data WEBER 80 TRONA SIERRA MADRE COUNTY Evanston AREA SWEETWATER COUNTY USGS study area boundaries MORGAN Bear River Watershed Area COUNTY UINTA COUNTY SALT WYOMING Southwestern and South Central Wyoming 41°0' LAKE Proposed withdrawal areas MIDDLE ROCKY DAGGETT MOUNTAINS COUNTY MOFFATT UINTA MOUNTAINS COUNTY State boundaries PROVINCE SUMMIT COLORADO COUNTY County boundaries Base modified from U.S. -

Land Without Roads” Wyoming’S Roadless Areas Are the State’S Hidden Gems by Molly Absolon

SPRING 2006 39 Years of Conservation Action R E P O R T More than a “land without roads” Wyoming’s roadless areas are the state’s hidden gems By Molly Absolon the easiest travel path in this land with no trails, thick vegetation and lots of small cliff bands to navi- gate. We scrambled around waterfalls cascading over moss-covered rock bands and crawled through tan- gled underbrush before the canyon floor opened up into a wide meadow sprinkled with late season asters. It was a beautiful, wild place. Canyon Creek, in the Shoshone National Forest, is just one of 115 inventoried roadless areas in Wyoming. Horseback riding is a popular Judy Inberg anuga “Roadless” is a technical term for national forest roadless area activity. lands greater than 5,000 acres that have no main- Jeff V tained roads and are essentially “natural.” In PAGE 5 long the eastern flanks of the Wind Wyoming, there are more than 3.2 million acres of Horse Whispering for a River Mountains, Canyon Creek slices designated roadless areas ranging in size from small Wild Backcountry down through layers of limestone, chunks like the 7,000-acre Canyon Creek parcel to dolomite and sandstone on its way the state’s largest, the 315,647-acre Grayback Roadless out of the mountains and into the Area in the Bridger-Teton National Forest. PAGE 6-7 Wind River Valley. The drainage created by the creek These special places are now up for grabs. President Roadless Area Users Aas it cuts down to the plains is similar to nearby Sinks Clinton’s roadless rule from 2001, which issued a Speak Out Canyon with its towering cliffs and sloping meadows, moratorium on future road building in these wild but Sinks Canyon is often crowded with visitors who lands, was overturned in 2005. -

Bridger-Teton National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2018 to 09/30/2018 Bridger-Teton National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) Amendments to Land - Land management planning In Progress: Expected:01/2019 02/2019 John Shivik Management Plans Regarding - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants NOI in Federal Register 801-625-5667 Sage-grouse Conservation 11/21/2017 [email protected] EIS Est. DEIS NOA in Federal *UPDATED* Register 06/2018 Description: The Forest Service is considering amending its land management plans to address new and evolving issues arising since implementing sage-grouse plans in 2015. This project is in cooperation with the USDI Bureau of Land Management. Web Link: https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r4/home/?cid=stelprd3843381 Location: UNIT - Ashley National Forest All Units, Boise National Forest All Units, Bridger-Teton National Forest All Units, Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest All Units, Medicine Bow-Routt National Forest All Units, Dixie National Forest All Units, Fishlake National Forest All Units, Salmon-Challis National Forest All Units, Sawtooth National Forest All Units, Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest All Units, Manti-La Sal National Forest All Units, Caribou- Targhee National Forest All Units, Uinta-Wasatch-Cache All Units. STATE - Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada,