Campfire (Medurat Hashevet)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Prayerbook for Shabbat Evening

“And They Answered You with Song” Kesher Community Siddur A Prayerbook For Shabbat Evening Editors: Joe Skloot ’05, Founding Editor Ben Amster ‘07 Joshua Packman ‘07 Jonah Perlin ‘07 With an introduction by Rabbi Julie Roth Princeton University Center for Jewish Life / Hillel 2002-2006 INTRODUCTION t is with great anticipation and joy that we present this siddur to the Reform Jewish I Community at Princeton. We want you to be proud to have this text as your own and hope that you are able to find inspiration from it for many years to come. The Princeton Reform Siddur Project began in 2003, before the current co-chairs matriculated, and it is an honor to be able to complete this endeavor. Before the first word of the prayerbook was written, there was a desire to produce a document that reflected both our desire to include as much of the traditional liturgy as practical and a firm commitment to include user friendly translations and personal meditations as well. For that reason, we have included the entire Kabblat Shabbat service as well as many additional songs and thoughts in the margins to encourage future service leaders to explore various aspects of the liturgy from one week to the next. The dilemma we faced when debating the extent to which our prayerbook would be traditional and the extent to which it would reflect our more liberal values revolved around our desire to allow individual worshipers the ability to draw their own interpretations from traditional texts. In our opinion, translating with poetic excellence or a desire to change the meanings of words for political correctness would create a prayerbook in which the part of the responsibility upon the reader has been limited by the writer. -

Pointing to the Torah and Other Hagbaha Customs

289 Pointing to the Torah and other Hagbaha Customs By: ZVI RON The idea of displaying the text of the Torah to the listening congre- gation is already found in Tanakh. Before Ezra read to the assem- bled Jews from the Torah scroll, we are told that “Ezra opened the scroll before the eyes of the people … and when he opened it, all the people stood silent. Ezra blessed the Lord God, and all the people answered, ‘Amen! Amen!’ with their hands upraised, then they bowed and prostrated themselves before the Lord, faces to the ground” (Neh. 8:5-6). It is not clear if the showing of the Torah and the reaction of bowing was meant to be a onetime practice or some- thing that would accompany every public Torah reading. Still, this source forms the basis of the idea of displaying the Torah scroll as codified in Masekhet Soferim 14:13.1 Just as reported in Nehemiah, Masekhet Soferim instructs that the Torah is to be shown before the reading, at which time the congregation should bow: “It is a mitz- vah for all the men and women to see the writing, bow and say, ‘This is the Torah that Moses placed before the Children of Israel’ (Deut. 4:44). ‘The Torah of the Lord is perfect, restoring the soul’ (Ps. 19:8).” This source is quoted by Ramban in his discussion of 1 See Morekhai Zer-Kavod, Da‘at Mikra: Ezra v–Nehemia (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1994), p. 105, note 6. See there also an alternate in- terpretation that the word vayiftah in this verse means “began reading” ra- ther than “opened.” According to that interpretation there was not neces- sarily a public display of the Torah at this event, and the people reacted to hearing the words of the Torah, rather than to seeing the scroll. -

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special Programs 215 345 6789

County Theater 79 PreviewsMARCH – MAY 2012 DAMSELS IN DISTRESS DAMSELS INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTY T HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. How can you support ADMISSION COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER General ..............................................................$9.75 Be a member. Members ...........................................................$5.00 Become a member of the nonprofit County Theater and Seniors (62+) show your support for good Students (w/ID) & Children (<18). ..................$7.25 films and a cultural landmark. See back panel for a member- Matinees ship form or join on-line. Your financial support is tax-deductible. Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 Make a gift. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .......................................$7.25 Your additional gifts and support make us even better. Your Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ..........................$5.00 donations are fully tax-deductible. And you can even put your Affiliated Theaters Members* .............................$6.00 name on a bronze star in the sidewalk! You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. Contact our Business Office at (215) 348-1878 x117 or at The above ticket prices are subject to change. [email protected]. Be a sponsor. *Affiliated Theaters Members Receive prominent recognition for your business in exchange The County Theater, the Ambler Theater, and the Bryn Mawr Film for helping our nonprofit theater. Recognition comes in a variety Institute have reciprocal admission benefits. Your membership will of ways – on our movie screens, in our brochures, and on our allow you $6.00 admission at the other theaters. -

Welcome to Eye Surgeons and Consultants! WE USE the MOST ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY and CUSTOMIZE OUR SERVICE to YOUR EYES!

Alan Mendelsohn, M.D. Nathan Klein, O.D. 954.894.1500 Welcome to Eye Surgeons and Consultants! WE USE THE MOST ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY AND CUSTOMIZE OUR SERVICE TO YOUR EYES! SERVICES For your convenience, we also have a full service optical dispensary Laser Cataract Surgery with the highest quality and huge selection of the latest styles of Laser Vision Correction eyeglasses and sunglasses, including: Glaucoma Laser Surgery Comprehensive Eye Exams Oliver Peoples • Michael Kors • Barton Perreira • Tom Ford • Burberry Macular Degeneration Marc Jacobs • Lily Pulitzer • Mont Blanc • Nike Flexon • Silhouette Diabetic Eye Exams Glaucoma Exams We provide personalized, professional care using Red Eye Evaluations a state-of-the-art computerized in-house laboratory. Dry Eye EXTENDED HOURS: MON: 7:30AM – 8:00PM Contact Lens Exams TUE – FRI: 7:30AM – 4:30PM • SUN: 7:30AM – 11:30AM Scleral Contact Lenses 4651 Sheridan Street, Suite 100, Hollywood, FL 33021 • 954.894.1500 PLEASE SEE OUR WEBSITE: www.myeyesurgeons.com for sight-saving suggestions! YOUNG ISRAEL OF HOLLYWOOD-FT. LAUDERDALE SEPTEMBER 2021 PAGE 3 FACTS I DISCOVERED WHILE LOOKING UP OTHER THINGS Rabbi Edward Davis JULIAN. On July 19, 362 CE, the new emperor, bath and to instruct the women about the rules of immersion. Constantine’s nephew, Julian, was in Antioch, on his way to When asked whether he was not afraid that his passion get invade Persia. He asked a Jewish delegation: “Why are you the better of him, he replied that to him the women looked not sacrificing?” The Jews answered, “We are not allowed. like so many white geese. -

Course Description Fall 2013

COURSE DESCRIPTION FALL 2013 TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL STUDY ABROAD ‐ FALL SEMESTER 2013 COURSE DESCRIPTION MAIN OFFICE UNITED STATES CANADA The Carter Building , Room 108 Office of Academic Affairs Lawrence Plaza Ramat Aviv, 6997801, Israel 39 Broadway, Suite 1510 3130 Bathurst Street, Suite 214 Phone: +972‐3‐6408118 New York, NY 10006 Toronto, Ontario M6A 2A1 Fax: +972‐3‐6409582 Phone: +1‐212‐742‐9030 [email protected] [email protected] Fax: +1‐212‐742‐9031 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL.TAU.AC.IL 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ■ FALL SEMESTER 2013 DATES 3‐4 ■ ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS 6‐17 O INSTRUCTIONS FOR REGISTRATION 6‐7 O REGULAR UNIVERSITY COURSES 7 O WITHDRAWAL FROM COURSES 8 O PASS/FAIL OPTION 8 O INCOMPLETE COURSES 8 O GRADING SYSTEM 9 O CODE OF HONOR AND ACADEMIC INTEGRITY 9 O RIGHT TO APPEAL 10 O SPECIAL ACCOMMODATIONS 10 O HEBREW ULPAN REGULATIONS 11 O TAU WRITING CENTER 11‐12 O DESCRIPTION OF LIBRARIES 13 O MOODLE 13 O SCHEDULE OF COURSES 14‐16 O EXAM TIMETABLE 17 ■ TRANSCRIPT REQUEST INSTRUCTIONS 18 ■ COURSE DESCRIPTIONS 19‐97 ■ REGISTRATION FORM FOR STUDY ABROAD COURSES 98 ■ EXTERNAL REGISTRATION FORM 99 2 FALL SEMESTER 2013 IMPORTANT DATES ■ The Fall Semester starts on Sunday, October 6th 2013 and ends on Thursday, December 19th 2013. ■ Course registration deadline: Thursday, September 8th 2013. ■ Class changes and finalizing schedule (see hereunder): October 13th – 14th 2013. ■ Last day in the dorms: Sunday, December 22nd 2013. Students are advised to register to more than the required 5 courses but not more than 7 courses. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Israeli Film Fest Returns Jan. 16, 23 Interfaith Panel at TI to Examine

January 2010 NoFebruaryvember 20062007 Tevet/Shevat 5770 Heshvan/KisleShevat/Adar v 5767 5767 2200 Baltimore Road •• Rockville, Rockville, Maryland Maryland 20850 20851 www.tikvatisrael.org VolumeVolume 41 •• NumberNumber 1 It’sFrom Show the Time!President’ Israelis FilmPerspective Fest Returns Jan. 16, 23 Weekly Religious Services Weekly Religious Services The.annual.Israeli.Film.Festival.at.Tikvat.Israel.will.feature.a.pair.of.movies.created.by. This new and handsome bulletin format that we will succeed more than we will Joseph.Cedar,.a.decorated.Israeli.film.director. Monday..........6:45.a.m........... 7:30.p.m. is a fortuitous metaphor for the many changes fail. We will witness the vibrant growth of Monday ....... 6:45 a.m. ........ 7:30 p.m. The.two.screenings.are.“Time.of.Favor”.on.Jan..16.and.“Campfire”.on.Jan..23..Both. Tuesday.................................. 7:30.p.m. that Tikvat Israel Congregation will be our community that some don’t expect, but films.will.begin.at.7:45.p.m..Tickets.are.$10.per.film.for.a.TI.member,.$12.for.a.non- Tuesday ................................. 7:30 p.m. experiencing this year. Rori Pollak will be that we all want. This has been my philosophy Wednesday............................. 7:30.p.m. [email protected]. joining us in June as new director of the and approach towards my own career as a ThursdayWednesday....................................6:45.a.m........... 7:307:30. p.m. Cedar.received.international.attention.with.the.release.of.his.2007.film.“Beaufort”. Broadman-Kaplan Early Childhood Center. scientist, co-chair of the AEC, and now as Friday.............6:45.a.m.......................... -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

ON the COVER: the Paul & Yetta Gluck School of Visual Arts Held Its First Class in January See Page 11 for Upcoming Class Options

The Jewish Journal Non-Profit Org. Monthly Magazine U.S. Postage PAID Youngstown, OH MM Permit #607 JJ Youngstown Area Jewish Federation February 2020 ON THE COVER: The Paul & Yetta Gluck School of Visual Arts Held Its First Class in January see page 11 for upcoming class options INSIDE: Mitzvah Day 2020 Will Include a Soup Cook-off see page 14 Where the Top Presidential Candidates Stand on Jewish Issues see page 18 YOUNGSTOWN AREA Volume 17, Number 2 • February 2020 • Shevat/Adar 5780 JEWISH FEDERATION Commentary Musings with Mary Lou: Women’s Heart Month By Mary Lou Finesilver Day comes in a close third. Interesting. problem. How can you correct something get them, and also a beautiful card from a Heart month celebration began in 1963 if you don’t know it is a problem? Of Did you know lovedeven flowers,one. One if year, you Iare reversed lucky itenough and sent to in order to bring more attention to heart course, we have all heard that diet and that February is diseases, etc. You know, heart disease can exercise are so necessary to keep the Women’s Heart to this day whether he was pleased or start as early as 18, so no one is immune. body going. It doesn’t necessarily make Month? It is embarrassed.my husband flowers I hope at he work. was I’mpleased. not sure He I think, in my uneducated mind, that it you immune, but it helps with recovery. recommended never really said, and I can no longer ask is women’s heart month because for so I know that exercise is very important to that men and him. -

Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: the Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication 5-3-2007 Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films ot Facilitate Dialogue Elana Shefrin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Shefrin, Elana, "Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE-MEDIATING THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT: THE USE OF FILMS TO FACILITATE DIALOGUE by ELANA SHEFRIN Under the Direction of M. Lane Bruner ABSTRACT With the objective of outlining a decision-making process for the selection, evaluation, and application of films for invigorating Palestinian-Israeli dialogue encounters, this project researches, collates, and weaves together the historico-political narratives of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, the artistic worldviews of the Israeli and Palestinian national cinemas, and the procedural designs of successful Track II dialogue interventions. Using a tailored version of Lucien Goldman’s method of homologic textual analysis, three Palestinian and three Israeli popular film texts are analyzed along the dimensions of Historico-Political Contextuality, Socio- Cultural Intertextuality, and Ethno-National Textuality. Then, applying the six “best practices” criteria gleaned from thriving dialogue programs, coupled with the six “cautionary tales” criteria gleaned from flawed dialogue models, three bi-national peacebuilding film texts are homologically analyzed and contrasted with the six popular film texts. -

Mediation in a Conflict Society an Ethnographic View on Mediation

The London School of Economics and Political Science Mediation in a Conflict Society An Ethnographic View on Mediation Processes in Israel Edite Ronnen A thesis submitted to the Department of Law of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2011 1 For Inbar, Ori and Eran לענבר, לאורי – שבלעדיהם אין לערן – שבגללו 2 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. 3 Abstract This thesis addresses the question: how do individuals in a conflict society engage in peaceful dispute resolution through mediation? It provides a close look at Israeli society, in which people face daily conflicts. These include confrontations on many levels: the national, such as wars and terror attacks; the social, such as ethnic, religious and economic tensions; and the personal level, whereby the number of lawyers and legal claims per capita are among the highest in the world. The magnitude, pervasiveness, and often existential nature of these conflicts have led sociologists to label Israel a ‘conflict society’. -

Pressed Minority, in the Diaspora

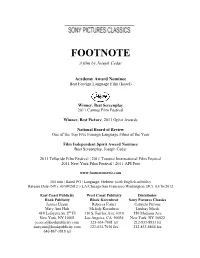

FOOTNOTE A film by Joseph Cedar Academy Award Nominee Best Foreign Language Film (Israel) Winner, Best Screenplay 2011 Cannes Film Festival Winner, Best Picture, 2011 Ophir Awards National Board of Review One of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of the Year Film Independent Spirit Award Nominee Best Screenplay, Joseph Cedar 2011 Telluride Film Festival | 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 New York Film Festival | 2011 AFI Fest www.footnotemovie.com 105 min | Rated PG | Language: Hebrew (with English subtitles) Release Date (NY): 03/09/2012 | (LA/Chicago/San Francisco/Washington, DC): 03/16/2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS FOOTNOTE is the tale of a great rivalry between a father and son. Eliezer and Uriel Shkolnik are both eccentric professors, who have dedicated their lives to their work in Talmudic Studies. The father, Eliezer, is a stubborn purist who fears the establishment and has never been recognized for his work. Meanwhile his son, Uriel, is an up-and-coming star in the field, who appears to feed on accolades, endlessly seeking recognition. Then one day, the tables turn. When Eliezer learns that he is to be awarded the Israel Prize, the most valuable honor for scholarship in the country, his vanity and desperate need for validation are exposed.