Sustainable Ecological Systems: Implementing an Ecological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report on Valley Silverspot Butterfly (Speyeria Zerene Bremnerii) Surveys in the Suislaw National Forest and Salem District BLM

Final report on Valley silverspot butterfly (Speyeria zerene bremnerii) surveys in the Suislaw National Forest and Salem District BLM Assistance agreement L08AC13768, Modification 7 Mill Creek proposed ACEC, Polk County, OR. Photo by Alexa Carleton Field work, background research, and report completed by Alexa Carleton, Candace Fallon, and Sarah Foltz Jordan, The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation October 30, 2012 Table of Contents Summary ….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…. 3 Introduction …….………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………….….… 3 Survey protocol …….………..…………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 4 Sites surveyed and survey results …..…….…………………………………………………………………………….…… 6 Northern Polk County sites (July 23) …………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Northern Benton County sites (July 24) ………………………………………………………………….….… 8 Southern Polk County sites (July 31) ………………………………………………………………………….. 11 Yamhill County sites (August 7)…………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Southern Benton County sites (August 12) ……………………………………………………………….… 13 Mary’s Peak, Benton County (August 15) ……………………………………………………….………..… 15 Potential future survey work…………….……………………………………………………………………………………. 20 Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 22 References .…………….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 22 Appendix I: Historic records of S. z. bremnerii in Oregon………………………………………………………... 23 Appendix II: Summary table of sites surveyed …….…………………………………………………………………. 27 Appendix III: Maps of sites surveyed ………………………………………………………..………………………….… -

To: Donita Cotter, Monarch Conservation Strategy Coordinator From: Dr. Benjamin N. Tuggle, Regional Director, Southwest

To: Donita Cotter, Monarch Conservation Strategy Coordinator From: Dr. Benjamin N. Tuggle, Regional Director, Southwest Region (R2) Subject: Region 2 Monarch Butterfly Conservation Strategy and Action Plan Template Date: November 12, 2014 On 4 September 2014, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Director issued a memorandum to the Service Directorate to develop a Service strategy for monarch conservation addressing plans for habitat restoration and enhancement, education and outreach, and monitoring and research needs. On October 7, the Director sent an email to all Regional Directors challenging them to commit to a goal of 100 Million Monarchs by 2020, and for Region 2 to provide a goal of 20,000 acres of new habitat for monarchs. The Director’s requests followed an agreement among President Obama, President Peña Nieto of Mexico, and Prime Minister Harper of Canada to “establish a working group to ensure the conservation of the Monarch butterfly, a species that symbolizes our association.” Also, on June 20, 2014, President Obama signed a Presidential Memorandum, “Creating a Federal Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators,” outlining an expedited agenda to address the devastating declines in honey bees and native pollinators, including the monarch butterfly. Secretary Jewell tasked the Director with convening an interagency High Level Working Group to develop and implement a U.S. strategy for monarch conservation, coordinate our efforts with Mexico and Canada through the Trilateral Committee, and ensure that the monarch strategy is coordinated with development of the Federal Pollinator Strategy and DOI assignments in the Presidential Memo. To accomplish these initiatives and provide information to update the 2008 North American Monarch Conservation Plan by March 2015 and completion of the Federal Pollinator Strategy due to the White House mid-December 2014, the following tasks were specifically requested in the Director’s memorandum: I. -

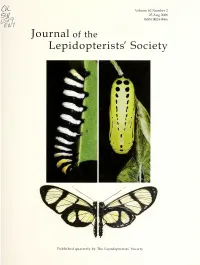

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society

J OURNAL OF T HE L EPIDOPTERISTS’ S OCIETY Volume 62 2008 Number 2 Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 61(2), 2007, 61–66 COMPARATIVE STUDIES ON THE IMMATURE STAGES AND DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY OF FIVE ARGYNNIS SPP. (SUBGENUS SPEYERIA) (NYMPHALIDAE) FROM WASHINGTON DAVID G. JAMES Department of Entomology, Washington State University, Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center, 24105 North Bunn Road, Prosser, Washington 99350; email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Comparative illustrations and notes on morphology and biology are provided on the immature stages of five Arg- ynnis spp. (A. cybele leto, A. coronis simaetha, A. zerene picta, A. egleis mcdunnoughi, A. hydaspe rhodope) found in the Pacific Northwest. High quality images allowed separation of the five species in most of their immature stages. Sixth instars of all species possessed a fleshy, eversible osmeterium-like gland located ventrally between the head and first thoracic segment. Dormant first in- star larvae of all species exposed to summer-like conditions (25 ± 0.5º C and continuous illumination), 2.0–2.5 months after hatch- ing, did not feed and died within 6–9 days, indicating the larvae were in diapause. Overwintering of first instars for ~ 80 days in dark- ness at 5 ± 0.5º C, 75 ± 5% r.h. resulted in minimal mortality. Subsequent exposure to summer-like conditions (25 ± 0.5º C and continuous illumination) resulted in breaking of dormancy and commencement of feeding in all species within 2–5 days. Durations of individual instars and complete post-larval feeding development durations were similar for A. coronis, A. zerene, A. egleis and A. -

2019 Monarch Conservation Implementation Plan

2019 Monarch Conservation Implementation Plan Prepared by the Monarch Joint Venture staff and partner organizations. 1 | Page Contents Executive Summary 3 Plan Priorities 4 Monarch Habitat Conservation, Maintenance and Enhancement 4 Education to Enhance Awareness of Monarch Conservation Issues and Opportunities 5 Research and Monitoring to Inform Monarch Conservation Efforts 5 Partnerships and collaboration to advance monarch conservation 5 Monarch Joint Venture Mission and Vision 6 2019 Monarch Conservation Implementation Plan 6 Priority 1: Monarch Habitat Conservation, Maintenance and Enhancement 7 Objective 1: Create, restore, enhance, and maintain habitat on public and private lands. 7 Objective 2: Develop consistent, regionally appropriate Asclepias and nectar resources for habitat enhancement and creation on public and private lands. 15 Objective 3: Address overwintering habitat issues in the United States. 18 Priority 2: Education to Enhance Awareness of Monarch Conservation Issues & Opportunities 19 Objective 1: Raise awareness to increase conservation actions and support for monarchs. 19 Objective 2: Increase learning about monarchs and their habitat in formal and informal settings. 24 Objective 3: Foster networking between stakeholders involved in monarch conservation. 26 Priority 3: Research and Monitoring to Inform Monarch Conservation Efforts 28 Objective 1: Study monarch habitat and population status. 28 Objective 2: Expand citizen science and other monitoring, data exchange, and data analyses to inform conservation efforts. -

1995-2006 Activities Report

WILDLIFE WITHOUT BORDERS WILDLIFE WITHOUT BORDERS WITHOUT WILDLIFE M E X I C O The most wonderful mystery of life may well be EDITORIAL DIRECTION Office of International Affairs U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service the means by which it created so much diversity www.fws.gov PRODUCTION from so little physical matter. The biosphere, all Agrupación Sierra Madre, S.C. www.sierramadre.com.mx EDITORIAL REVISION organisms combined, makes up only about one Carole Bullard PHOTOGRAPHS All by Patricio Robles Gil part in ten billion [email protected] Excepting: Fabricio Feduchi, p. 13 of the earth’s mass. [email protected] Patricia Rojo, pp. 22-23 [email protected] Fulvio Eccardi, p. 39 It is sparsely distributed through MEXICO [email protected] Jaime Rojo, pp. 44-45 [email protected] a kilometre-thick layer of soil, Antonio Ramírez, Cover (Bat) On p. 1, Tamul waterfall. San Luis Potosí On p. 2, Lacandon rainforest water, and air stretched over On p. 128, Fisherman. Centla wetlands, Tabasco All rights reserved © 2007, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service a half billion square kilometres of surface. The rights of the photographs belongs to each photographer PRINTED IN Impresora Transcontinental de México EDWARD O. WILSON 1992 Photo: NASA U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE DIVISION OF INTERNATIONAL CONSERVATION WILDLIFE WITHOUT BORDERS MEXICO ACTIVITIES REPORT 1995-2006 U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE At their roots, all things hold hands. & When a tree falls down in the forest, SECRETARÍA DE MEDIO AMBIENTE Y RECURSOS NATURALES MEXICO a star falls down from the sky. CHAN K’IN LACANDON ELDER LACANDON RAINFOREST CHIAPAS, MEXICO FOREWORD onservation of biological diversity has truly arrived significant contributions in time, dedication, and C as a global priority. -

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society

Volume 62 Number 2 25 Aug 2008 ISSN 0024-0966 Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society Published quarterly by The Lepidopterists' Society ) ) THE LEPIDOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY Executive Council John H. Acorn, President John Lill, Vice President William E. Conner, Immediate Past President David D. Lavvrie, Secretary Andre V.L. Freitas, Vice President Kelly M. Richers, Treasurer Akito Kayvahara, Vice President Members at large: Kim Garwood Richard A. Anderson Michelle DaCosta Kenn Kaufman John V. Calhoun John H. Masters Plarry Zirlin Amanda Roe Michael G. Pogue Editorial Board John W. Rrovvn {Chair) Michael E. Toliver Member at large ( , Brian Scholtens (Journal Lawrence F. Gall ( Memoirs ) 13 ale Clark {News) John A. Snyder {Website) Honorary Life Members of the Society Charles L. Remington (1966), E. G. Munroe (1973), Ian F. B. Common (1987), Lincoln P Brower (1990), Frederick H. Rindge (1997), Ronald W. Hodges (2004) The object of The Lepidopterists’ Society, which was formed in May 1947 and formally constituted in December 1950, is “to pro- mote the science of lepidopterology in all its branches, ... to issue a periodical and other publications on Lepidoptera, to facilitate the exchange of specimens and ideas by both the professional worker and the amateur in the field; to secure cooperation in all mea- sures” directed towards these aims. Membership in the Society is open to all persons interested in the study of Lepidoptera. All members receive the Journal and the News of The Lepidopterists’ Society. Prospective members should send to the Assistant Treasurer full dues for the current year, to- gether with their lull name, address, and special lepidopterological interests. -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 234 / Friday, December 5, 1997 / Rules and Regulations

64306 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 234 / Friday, December 5, 1997 / Rules and Regulations Authority: 46 U.S.C. 2103, 3306; E.O. SUBCHAPTER TÐSMALL PART 177ÐCONSTRUCTION AND 12234, 45 FR 58801, 3 CFR, 1980 Comp., p. PASSENGER VESSELS (UNDER 100 ARRANGEMENT 277; 49 CFR 1.46. GROSS TONS) 20. The authority citation for part 177 § 121.710 [Corrected] continues to read as follows: PART 175ÐGENERAL PROVISIONS 15. In § 121.710, remove the words Authority: 46 U.S.C. 2103, 3306; E.O. ``part 160, subpart 160.041, of this 18. The authority citation for part 175 12234, 45 FR 58801, 3 CFR, 1980 Comp., p. chapter'' and add, in their place, the 277; 49 CFR 1.46. words ``approval series 160.041''. continues to read as follows: 21. In § 177.500, in paragraph (j)(1), Authority: 46 U.S.C. 2103, 3306; 49 U.S.C. remove the last word ``and'' and add, in PART 122ÐOPERATIONS App. 1804; 49 CFR 1.45, 1.46. Sec. 175.900 its place, the word ``or''; and revise also issued under 44 U.S.C. 3507. 16. The authority citation for part 122 paragraph (o)(1) to read as follows: continues to read as follows: 19. In § 175.400, in the definition for § 177.500 Means of escape. Authority: 46 U.S.C. 2103, 3306, 6101; E.O. ``High Speed Craft'', in the equation ``V 12234, 45 FR 58801, 3 CFR, 1980 Comp., p. = 3.7 × displ 1667 h'', add a decimal point * * * * * 277; 49 CFR 1.46. (o) * * * before the number ``1667'', and add, in (1) The space has a deck area less than § 122.604 [Corrected] alphabetical order, a definition for 30 square meters (322 square feet); ``wood vessel'' to read as follows: 17. -

Conservation Biology of Tile Marsh Fritillary Butterfly Euphydryas a Urinia

CONSERVATION BIOLOGY OF TILE MARSH FRITILLARY BUTTERFLY EUPHYDRYAS A URINIA CAROLINE ROSE BULMAN Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Biology Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to Chris Thomas for his constant advice, support, inspiration and above all enthusiasm for this project. Robert Wilson has been especially helpful and I am very grateful for his assistance, in particular with the rPM. Alison Holt and Lucia Galvez Bravo made the many months of fieldwork both productive and enjoyable, for which I am very grateful. Thanks to Atte Moilanen for providing advice and software for the IFM, Otso Ovaskainen for calculating the metapopulation capacity and to Niklas Wahlberg and Ilkka Hanski for discussion. This work would have been impossible without the assistance of the following people andlor organisations: Butterfly Conservation (Martin Warren, Richard Fox, Paul Kirland, Nigel Bourn, Russel Hobson) and Branch volunteers (especially Bill Shreeve and BNM recorders), the Countryside Council for Wales (Adrian Fowles, David Wheeler, Justin Lyons, Andy Polkey, Les Colley, Karen Heppingstall), English Nature (David Sheppard, Dee Stephens, Frank Mawby, Judith Murray), Dartmoor National Park (Norman Baldock), Dorset \)Ji\thife Trust (Sharoii Pd'bot), )eNorI Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Somerset Wildlife Trust, the National Trust, Dorset Environmental Records Centre, Somerset Environmental Records Centre, Domino Joyce, Stephen Hartley, David Blakeley, Martin Lappage, David Hardy, David & Liz Woolley, David & Ruth Pritchard, and the many landowners who granted access permission. -

Searching for Oregon Silverspot Butterfly (Speyeria Zerene Hippolyta

Use of Canines to Detect Early Life History Stages of a Threatened Butterfly Cody Burkhart Rich Van Buskirk Environmental Science Pacific University Extinction Rates Ceballos et al., 2015 Taxonomic Bias • International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) • Endangered Species Act (ESA) • Documenting insect extinctions are currently underrepresented (Dunn, 2005) 500 450 400 350 300 250 200 Number ofSpecies Number Insects 150 100 50 0 Vertebrates Invertebrates Mammals Birds Reptiles Amphibians Fishes Clams Snails Insects Arachnids Crustaceans Corals U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, 2017 Causes of Decline 90 80 70 60 50 40 Percentage 30 20 10 0 Resource Use Exotic Species Construction Altered Habitat Agriculture Species Pollution Water Dynamics Interactions Diversions (non-exotics) Lawler et al., 2002 Insect Conservation: Large Blue Butterfly (Maculinea arion) Photo By: PJC&CO from Wikimedia Commons Large Blue Butterfly • Early responses focused on habitat restoration • Critical life history stage relied on Myrmica sabuleti ants • Extirpated in the UK in 1979 Conservation Implications • Species decline can be reversible • Understanding life history is essential Oregon Silverspot Butterfly (Speyeria zerene hippolyta) • OSB Habitat: – Early successional communities – Salt-spray meadows – Oregon Coast and northern California coast. – Extirpated in Washington. • Larval host plant: early blue violet (Viola adunca) (Oregon Zoo 2009) History of Decline • Habitat loss U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2001 Remaining Threats • Succession 6000 • Invasive species 5000 4000 3000 Cascade Head Rock Creek Mount Hebo 2000 Oregon Silverspot Butterfly Population Numbers Population Butterfly Silverspot Oregon 1000 0 Year OSB Life Cycle Oregon Zoo, 2009 The Conservation Canines Project • Determine feasibility of using scent detection dogs to locate cryptic life history stages • Assess dynamics of pilot search project Mt. -

Conservation Overview of Butterflies in the Southern Headwaters at Risk Project (SHARP) Area

Conservation Overview of Butterflies in the Southern Headwaters at Risk Project (SHARP) Area Al Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 80 Conservation Overview of Butterflies in the Southern Headwaters at Risk Project (SHARP) Area Norbert G. Kondla Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 80 January 2004 Publication No. I/136 ISBN: 0-7785-2954-1 (Printed Edition) ISBN: 0-7785-2955-X (On-line Edition) ISSN: 1496-7219 (Printed Edition) ISSN: 1496-7146 (On-line Edition) Cover photograph: Norbert Kondla, Plebejus melissa (Melissa Blue), Maycroft, AB For copies of this report, contact: Information Centre- Publications Alberta Environment/ Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920- 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment/ Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115- 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297- 3362 OR Visit our web site at: http://www3.gov.ab.ca/srd/fw/riskspecies/ This publication may be cited as: Kondla, N.G. 2004. Conservation overview of butterflies in the southern headwaters at risk project (SHARP) area. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 80. Edmonton, AB. 35 pp. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................................ ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................